Electorate of Bavaria

The Electorate of Bavaria (German: Kurfürstentum Bayern) was an independent hereditary electorate of the Holy Roman Empire from 1623 to 1806, when it was succeeded by the Kingdom of Bavaria.[3]

Electorate of Bavaria Kurfürstentum Bayern | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1623–1806 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

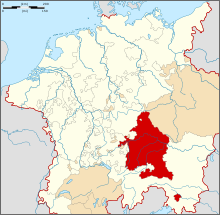

Bavaria highlighted on a map of the Holy Roman Empire in 1648 | |||||||||

| Status | Electorate | ||||||||

| Capital | Munich | ||||||||

| Government | Feudal monarchy | ||||||||

| Elector of Bavaria | |||||||||

• 1623–1651 | Maximilian I, Elector of Bavaria | ||||||||

• 1651–1679 | Ferdinand Maria, Elector of Bavaria | ||||||||

• 1679–1726 | Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria | ||||||||

• 1726–1745 | Karl Albrecht, Elector of Bavaria | ||||||||

• 1745–1777 | Maximilian III Joseph, Elector of Bavaria | ||||||||

• 1777–1799 | Karl Theodor, Elector of Bavaria | ||||||||

• 1799–1805 | Maximilian IV Joseph, Elector of Bavaria | ||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern Europe | ||||||||

• Granted electoral dignity | 1623 | ||||||||

• Peace of Westphalia | 1648 | ||||||||

• Put under Imperial Ban | 1706 | ||||||||

• Imperial Ban reversed | 1714 | ||||||||

1777 | |||||||||

• Raised to kingdom | 1806 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Wittelsbach dynasty which ruled the Duchy of Bavaria was the younger branch of the family which also ruled the Electorate of the Palatinate. The head of the elder branch was one of the seven prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire according to the Golden Bull of 1356, but Bavaria was excluded from the electoral dignity. In 1621, the Elector Palatine Frederick V was put under the imperial ban for his role in the Bohemian Revolt against Emperor Ferdinand II, and the electoral dignity and territory of the Upper Palatinate was conferred upon his loyal cousin, Duke Maximilian I of Bavaria. Although the Peace of Westphalia would create a new electoral title for Frederick V's son, with the exception of a brief period during the War of the Spanish Succession, Maximilian's descendants would continue to hold the original electoral dignity until the extinction of his line in 1777. At that point the two lines were joined in personal union until the end of the Holy Roman Empire. In 1805, after the Peace of Pressburg, the then-elector, Maximilian Joseph, raised himself to the dignity of King of Bavaria, and the Holy Roman Empire was abolished the year after.

Geography

The Electorate of Bavaria consisted of most of the modern regions of Upper Bavaria, Lower Bavaria, and the Upper Palatinate. Before 1779, it also included the Innviertel, now part of modern Austria. This was ceded to the Habsburgs by the Treaty of Teschen, which ended the War of the Bavarian Succession. There were a considerable number of independent enclaves and jurisdictions within those broad areas, however, including the principalities of Palatinate-Neuburg and Palatinate-Sulzbach in the Upper Palatinate, which were held by cadet branches of the Palatinate line of the Wittelsbachs; the ecclesiastical states of Freising, Regensburg, and Passau, and the imperial free city of Regensburg. For administration purposes Bavaria was already from 1507 divided into four stewardships (Rentamt): Munich, Burghausen, Landshut and Straubing. With the acquisition of the Upper Palatinate during the Thirty Years' War the stewardship Amberg was added. In 1802 they were abolished by the minister Maximilian von Montgelas. In 1805 shortly before the elevation Tirol and Vorarlberg were united with Bavaria, same as several of these enclaves.

Dignities

By virtue of his electoral title, the Elector of Bavaria was a member of the Council of Electors in the Imperial Diet as well as Archsteward of the Holy Roman Empire; he also held the dignity of Imperial Vicar during imperial vacancies along with the Elector of Saxony, a duty he undertook in 1657–1658, 1740–1742, 1745, 1790, and 1792. In the Council of Princes of the Diet prior to the personal union of 1777 he held individual voices as Duke of Bavaria and (after 1770) Princely Landgrave of Leuchtenberg. In the Imperial Circles he was, along with the Archbishop of Salzburg, co-Director of the Bavarian Circle, a circle territorially dominated by the elector's lands. He also held lands in the Swabian Circle. After 1777 these lands were joined by all of the Palatine lands, including the Electorate of the Palatinate, the Duchies of Jülich and Berg, Palatinate-Neuburg, Palatinate-Sulzbach, Palatinate-Veldenz, and other territories.

History

Thirty Years' War

When he had succeeded to the throne of the duchy of Bavaria in 1597, Maximilian I had found it encumbered with debt and filled with disorder, but ten years of his vigorous rule effected a remarkable change. The finances and the judicial system were reorganised, a class of civil servants and a national militia founded, and several small districts were brought under the duke's authority. The result was a unity and order in the duchy which enabled Maximilian to play an important part in the Thirty Years' War; during the earlier years of which he was so successful as to acquire the Upper Palatinate and the electoral dignity which had been enjoyed since 1356 by the elder branch of the Wittelsbach family. In spite of subsequent reverses, Maximilian retained these gains at the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. During the later years of this war Bavaria, especially the northern part, suffered severely. In 1632 the Swedes invaded, and when Maximilian violated the treaty of Ulm in 1647, the French and the Swedes ravaged the land. After repairing this damage to some extent, the elector died at Ingolstadt in September 1651, leaving his duchy much stronger than he had found it. The recovery of the Upper Palatinate made Bavaria compact; the acquisition of the electoral vote made it influential; and the duchy was able to play a part in European politics which internal strife had rendered impossible for the past four hundred years.

Absolutism

Whatever lustre the international position won by Maximilian I might add to the ducal house, on Bavaria itself its effect during the next two centuries was more dubious. Maximilian's son, Ferdinand Maria (1651–1679), who was a minor when he succeeded, did much indeed to repair the wounds caused by the Thirty Years' War, encouraging agriculture and industries, and building or restoring numerous churches and monasteries. In 1669, moreover, he again called a meeting of the diet, which had been suspended since 1612.

His constructive work, however, was largely undone by his son Maximilian II Emanuel (1679–1726), whose far-reaching ambition set him warring against the Ottoman Empire and, on the side of France, in the great struggle of the Spanish succession. He shared in the defeat at the Battle of Blenheim, near Höchstädt, on 13 August 1704; his dominions were temporarily partitioned between Austria and the elector palatine by the Treaty of Ilbersheim, and only restored to him, harried and exhausted, at the Treaty of Baden in 1714; the first Bavarian peasant insurrection, known as the Bloody Christmas of Sendling, having been crushed by the Austrian occupators in 1706.

Untaught by Maximilian II Emmanuel's experience, his son, Charles Albert (1726–1745), devoted all his energies to increasing the European prestige and power of his house. The death of the emperor Charles VI proved his opportunity: he disputed the validity of the Pragmatic Sanction which secured the Habsburg succession to Maria Theresa, allied himself with France, conquered Upper Austria, was crowned king of Bohemia at Prague and, in 1742, emperor at Frankfurt. The price he had to pay, however, was the occupation of Bavaria itself by Austrian troops; and, though the invasion of Bohemia in 1744 by Frederick II of Prussia enabled him to return to Munich, at his death on 20 January 1745 it was left to his successor to make what terms he could for the recovery of his dominions.

Maximilian III Joseph (1745–1777), by the peace of Füssen signed on 22 April 1745, obtained the restitution of his dominions in return for a formal acknowledgment of the Pragmatic Sanction. He was a man of enlightenment, did much to encourage agriculture, industries and the exploitation of the mineral wealth of the country, founded the Academy of Sciences at Munich, and abolished the Jesuit censorship of the press. At his death, without issue, on 30 December 1777, the Bavarian line of the Wittelsbachs became extinct, and the succession passed to Charles Theodore, the elector palatine. After a separation of four and a half centuries, the Electorate of the Palatinate, to which the duchies of Jülich and Berg had been added, was thus reunited with Bavaria.

Palatinate-Bavaria

.jpg)

So great an accession of strength to a neighbouring state, whose ambition she had so recently had just reason to fear, proved intolerable to Austria, which laid claim to a number of lordships —forming one-third of the whole Bavarian inheritance – as lapsed fiefs of the Bohemian, Austrian, and imperial crowns. These were at once occupied by Austrian troops, with the secret consent of Charles Theodore himself, who was without legitimate heirs, and wished to obtain from the emperor the elevation of his natural children to the status of princes of the Empire. The protests of the next heir, Charles II, Duke of Zweibrücken (Deux-Ponts), supported by the king of Prussia, led to the War of Bavarian Succession. By the peace of Teschen (13 May 1779) the Innviertel was ceded to Austria, and the succession secured to Charles of Zweibrücken.

For Bavaria itself Charles Theodore did less than nothing. He felt himself a foreigner among foreigners, and his favourite scheme, the subject of endless intrigues with the Austrian cabinet and the immediate cause of Frederick II's League of Princes (Fürstenbund) of 1785, was to exchange Bavaria for the Austrian Netherlands and the title of king of Burgundy. For the rest, the enlightened internal policy of his predecessor was abandoned. The funds of the suppressed order of Jesus, which Maximilian Joseph had destined for the reform of the educational system of the country, were used to endow a province of the knights of St John of Jerusalem, for the purpose of combating the enemies of the faith. The government was inspired by the narrowest clericalism, which culminated in the attempt to withdraw the Bavarian bishops from the jurisdiction of the great German metropolitans and place them directly under that of the pope. On the eve of the Revolution the intellectual and social condition of Bavaria remained that of the Middle Ages.

Revolutionary and Napoleonic periods

In 1792 French revolutionary armies overran the Palatinate; in 1795 the French, under Moreau, invaded Bavaria itself, advanced to Munich – where they were received with joy by the long-suppressed Liberals – and laid siege to Ingolstadt. Charles Theodore, who had done nothing to prevent wars or to resist the invasion, fled to Saxony, leaving a regency, the members of which signed a convention with Moreau, by which he granted an armistice in return for a heavy contribution (7 September 1796).

Between the French and the Austrians, Bavaria was now in a bad situation. Before the death of Charles Theodore (16 February 1799) the Austrians had again occupied the country, in preparation for renewing the war with France. Maximilian IV Joseph (of Zweibrücken), the new elector, succeeded to a difficult inheritance. Though his own sympathies, and those of his all-powerful minister, Maximilian von Montgelas, were, if anything, French rather than Austrian, the state of the Bavarian finances, and the fact that the Bavarian troops were scattered and disorganized, placed him helpless in the hands of Austria; on 2 December 1800 the Bavarian arms were involved in the Austrian defeat at Hohenlinden, and Moreau once more occupied Munich. By the Treaty of Lunéville (9 February 1801) Bavaria lost the Palatinate and the duchies of Zweibrücken and Jülich.

In view of the scarcely disguised ambitions and intrigues of the Austrian court, Montgelas now believed that the interests of Bavaria lay in a frank alliance with the French Republic; he succeeded in overcoming the reluctance of Maximilian Joseph; and, on 24 August, a separate treaty of peace and alliance with France was signed at Paris. By the third article of this the First Consul undertook to see that the compensation promised under the 7th article of the treaty of Lunéville for the territory ceded on the left bank of the Rhine, should be carried out at the expense of the Empire in the manner most agreeable to Bavaria (see de Martens, Recueil, vol. vii. p. 365).

In 1803, accordingly, in the territorial rearrangements consequent on Napoleon's suppression of the ecclesiastical states, and of many free cities of the Empire, Bavaria received the bishoprics of Würzburg, Bamberg, Augsburg and Freisingen, part of that of Passau, the territories of twelve abbeys, and seventeen cities and villages, the whole forming a compact territory which more than compensated for the loss of her outlying provinces on the Rhine. Montgelas now aspired to raise Bavaria to the rank of a first-rate power, and he pursued this object during the Napoleonic epoch with consummate skill, allowing fully for the preponderance of France – so long as it lasted – but never permitting Bavaria to sink, like so many of the states of the Confederation of the Rhine, into a mere French dependency.

In the war of 1805, in accordance with a treaty of alliance signed at Würzburg on 23 September, Bavarian troops, for the first time since the days of Charles VII, fought side by side with the French, and by the Treaty of Pressburg, signed on 26 December, the Principality of Eichstädt, the Margravate of Burgau, the Lordship of Vorarlberg, the countships of Hohenems and Königsegg-Rothenfels, the lordships of Argen and Tettnang, and the city of Lindau with its territory were to be added to Bavaria. On the other hand, Würzburg, obtained in 1803, was to be ceded by Bavaria to the elector of Salzburg in exchange for Tirol . By the 1st article of the treaty the emperor acknowledged the assumption by the elector of the title of king, as Maximilian I. The price which Maximilian had reluctantly to pay for this accession of dignity was the marriage of his daughter Augusta with Eugène de Beauharnais.

End of the Electorate of Bavaria

The Elector declared himself to be king on 1 January 1806, officially changing the Electorate of Bavaria to being the Kingdom of Bavaria. On 15 March 1806 he ceded the Duchy of Berg to Napoleon. Shortly thereafter, the Confederation of the Rhine was formed and Maximilian, with the other princes who joined that body, announced his secession from the Holy Roman Empire. The King still served as an Elector until Bavaria left the Holy Roman Empire (1 August 1806). A few days later, on 6 August 1806, the Holy Roman Empire was dissolved after surviving for a thousand years.

See also

References

- Based on original preserved depictions:

The catholic Church of St. Johann Baptist in Oberviechtach

The catholic Church of St. Johann Baptist in Oberviechtach- The catholic Church of the Visitation of the Virgin Mary in Gottmannshofen

- Based on original preserved depictions:

The catholic Church of St. Johann Baptist in Oberviechtach

The catholic Church of St. Johann Baptist in Oberviechtach- The catholic Church of the Visitation of the Virgin Mary in Gottmannshofen

- Otto Von Pivka (November 1980). Napoleon's German Allies. Osprey Publishing. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-0-85045-373-7. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

.svg.png)

.svg.png)