Battle of Rossbach

The Battle of Rossbach took place on 5 November 1757 during the Third Silesian War (1756–1763, part of the Seven Years' War) near the village of Rossbach (Roßbach), in the Electorate of Saxony. It is sometimes called the Battle of, or at, Reichardtswerben, after a different nearby town. In this 90-minute battle, Frederick the Great, king of Prussia, defeated an Allied army composed of French forces augmented by a contingent of the Reichsarmee (Imperial Army) of the Holy Roman Empire. The French and Imperial army included almost 42,000 men, opposing a considerably smaller Prussian force of 22,000. Despite overwhelming odds, Frederick employed rapid movement, a flanking maneuver and oblique order to achieve complete surprise.

The Battle of Rossbach marked a turning point in the Seven Years' War, not only for its stunning Prussian victory, but because France refused to send troops against Prussia again and Britain, noting Prussia's military success, increased its financial support for Frederick. Following the battle, Frederick immediately left Rossbach and marched for 13 days to the outskirts of Breslau. There he met the Austrian army at the Battle of Leuthen; he employed similar tactics to again defeat an army considerably larger than his own.

Rossbach is considered one of Frederick's greatest strategic masterpieces. He crippled an enemy army twice the size of the Prussian force while suffering negligible casualties. His artillery also played a critical role in the victory, based on its ability to reposition itself rapidly responding to changing circumstances on the battlefield. Finally, his cavalry contributed decisively to the outcome of the battle, justifying his investment of resources into its training during the eight-year interim between the conclusion of the War of Austrian Succession and the outbreak of the Seven Years' War.

Seven Years' War

Although the Seven Years' War was a global conflict, it took a specific intensity in the European theater based on the recently concluded War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). The 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle concluded the earlier war in which Prussia and Austria were a part; its influence among the European powers was little better than a truce. Frederick II of Prussia, known as Frederick the Great, acquired the prosperous province of Silesia, but had wanted much of the Saxon territories as well. Empress Maria Theresa of Austria had signed the treaty to gain time to rebuild her military forces and forge new alliances; she was intent upon regaining ascendancy in the Holy Roman Empire.[1] By 1754, escalating tensions between Britain and France in North America offered the Empress the opportunity to regain her lost Central European territories and to limit Prussia's growing power. Similarly, France sought to break the British control of Atlantic trade. France and Austria put aside their old rivalry to form a coalition of their own. Faced with this sudden turn of events, the British king, George II, aligned himself with his nephew, Frederick, and the Kingdom of Prussia; this alliance drew in not only the British king's territories held in personal union, including Hanover, but also those of his and Frederick's relatives in the Electorate of Hanover and the Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel. This series of political maneuvers became known as the Diplomatic Revolution.[2]

Situation in 1757

At the start of the war, Frederick had one of the finest armies in Europe: his troops—any company—could fire at least four musket volleys a minute, and some of them could fire five; his army could march 20–32 km (12–20 mi) a day, and was able to conduct, under fire, some of the most complex maneuvers known.[3] After overrunning Saxony, Frederick campaigned in Bohemia and defeated the Austrians on 6 May 1757 at the Battle of Prague. He was initially successful, but after the Battle of Kolín, everything went awry: what had started as a war of movement by Frederick's agile army turned into a war of attrition.[4]

By summer 1757, Prussia was threatened on two fronts. In the east, the Russians, under Field Marshal Stepan Fyodorovich Apraksin, besieged Memel with 75,000 troops. Memel had one of the strongest fortresses in Prussia, but after five days of artillery bombardment, the Russian army successfully stormed it.[5] The Russians then used Memel as a base to invade East Prussia and defeated a smaller Prussian force in the fiercely contested Battle of Gross-Jägersdorf on 30 August 1757. However, the Russians were unable to take Königsberg, the capital of East Prussia, after using up their supplies of cannonballs at Memel and Gross-Jägersdorf, and retreated soon afterward. The logistics of supplying a large army remained a problem for the Russians throughout the war.[6] Although previous experiences in wars with the Ottoman Empire had exposed these problems, the Russians had not solved the challenge of supplying their army at a distance from Moscow.[7] Even so, the Imperial Russian Army offered a new threat to Prussia, forcing Frederick to abandon his invasion of Bohemia and to withdraw further into Prussian territory.[8]

In Saxony and Silesia, the Austrian forces slowly reclaimed territory held by Frederick earlier in the year. In September, at the Battle of Moys, Prince Charles's Austrians defeated the Prussians commanded by Hans Karl von Winterfeldt, one of Frederick's most trusted generals, who was killed in the battle.[9] As summer ended, a combined force of French and the Reichsarmee (Imperial Army) troops, approaching from the west, intended to unite with Prince Charles's main Austrian force, which itself advanced west to Breslau. Prince Soubise and Prince Joseph of Saxe-Hildburghausen shared command of the Allied force.[10]

If these armies were to unite, Prussia's situation would be dire indeed. Recognizing this threat, Frederick used the strategy of interior lines to advance in a quick, arduous march reminiscent of the forced marches of his great grandfather, Frederick William I, the "Great Elector". An army marches only as fast as its slowest components, which are usually the supply trains, and Frederick obtained needed supplies ahead of the army, which enabled him to abandon his supply wagons. His army covered 274 km (170 mi) in only 13 days. Bringing his enemy to battle proved difficult, as the Allies flitted out of his reach. Both Frederick and his enemies moved back and forth for several days, trying to maneuver around each other but ending up in a stalemate. During this time, an Austrian raiding party attacked Berlin and almost captured the Prussian royal family.[6]

Terrain and maneuver

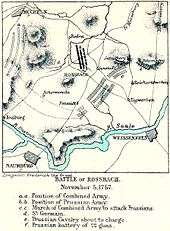

The story of the Battle of Rossbach is as much the story of the five days of maneuver leading to the battle as it is of those famous 90 minutes of battle, and the maneuvers were shaped by the terrain. Initial activity focused on the village of Weissenfels, where the middle Saale emerges from the Buntsandstein of the Thuringian Basin in the Leipzig highlands, not far from the modern-day A9 highway. Parts of the valley between Leipzig and Saale were relatively narrow, cut by the river and its tributaries; the hillsides were steep, and there were limited river crossings; this influenced the troop movements leading to the battle, as the various armies competed for sites to cross the river.[11]

The scene of the battle, Rossbach, lay 14 km (9 mi) southwest of Merseburg on a wide plateau dotted by hillocks with elevations up to 120–245 m (394–804 ft).[12] The locale was a wide plain largely without trees or hedges. The ground was sandy in some areas, and marshy in others; a small stream ran between Rossbach and Merseburg, south of which rose two low hills, the Janus and the Pölzen. Thomas Carlyle later described these as unimpressive, although certainly horses dragging cannons would notice them, as the animals slipped in loose stones and sand. To the west, the Saale flowed past a small town of Weissenfels, a few miles southeast of Rossbach.[11]

- Rossbach and Environs

- Small copses of trees broke the landscape. (Near Reichardtswerben)

- Gentle elevation changes created little natural cover for troop movements. (Near Branderoda)

Thomas Carlyle referred to the hills as negligible.

Thomas Carlyle referred to the hills as negligible.- The Saale flowed past Weissenfels, a few miles southeast of Rossbach.

On 24 October, the Prussian Field Marshal James Keith was in Leipzig when the Imperial Army occupied Weissenfels. Frederick joined him there two days later. Over the next couple of days, the King's brother, Prince Henry, arrived with the main body of the army and his brother-in-law, Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, arrived from Magdeburg. Prince Moritz of Anhalt-Dessau arrived by 28 October; although his men had marched up to 43 km (27 mi) in a day, they were still eager to face the Allied forces, who had established a post close to Markranstädt, and maintained some line of control along the Saale river.[13] This gave Prussia a complement of 22,000 men.[14] On 30 October, the King led the army out of Leipzig, toward Lützen, with Colonel Johann von Mayr and his Freibatallion, an independent unit of 1500 mixed troops,[Note 1] in the lead to flush out Allied pickets and reconnaissance parties; this cleared the way for the main army. The next day, Frederick moved out of Lützen at 3:00 pm, during heavy rain. Despite the weather, the Széchenyi Hussars harassed their line of march, but, in the hussars' eagerness to annoy the Prussians, they forgot to send a messenger to Weissenfels to warn the garrison of the Prussian approach. When Mayr appeared at about 8:00 a.m. on the 31st, followed by the King and the rest of his army, the French were completely surprised. The force there consisted of four battalions and 18 companies of grenadiers, all but three of them French: 5,000 men under command of Louis, Duke de Crillon.[13]

Crillon closed up the town and prepared for action. The Prussians unlimbered their artillery and fired on the town gates; Mayr's men and the Prussian grenadiers knocked out the obstructions. A few precise hits cleared their way into the town and the Allied resistance disappeared in cannon smoke; the Allied troops rapidly withdrew from the town across the bridge over the Saale and, as they withdrew, they set fire to the bridge to prevent the Prussians from following them. A conflagration consumed the wooden bridge so rapidly that 630 men, most of the garrison, were trapped on the wrong side. They surrendered with their arms and equipment. Saxe-Hildburghausen, at Burgwerben, ordered a barrage laid down across the Saale to prevent the Prussians from repairing the bridge. Frederick's gunners responded in kind and the two shelled each other until about 3:00 pm.[16]

While the artilleries kept up their noisy exchange, holding the Duke's attention, Frederick sent scouts to find a decent crossing of the Saale, since the one at Weissenfels was not usable. There was little he could do at the burned bridge; to cross the river under Saxe-Hildburghausen's nose, in the face of fire, would have been foolish. Across the river, the Allies had a physical barrier to protect them; they could also use their position to watch Frederick's movement. Inexplicably, though, Saxe-Hildburghausen gave up this advantage and retired toward Burgwerben and Tagewerben, counting on the intervening hills to protect him. Soubise had advanced from Reichardtswerben through Kaynau, and they met up at Großkorbetha. Their advanced guard patrolled Merseburg, and sought some information from the local inhabitants. Although the local Saxon peasants might have disliked the Prussians, they disliked the French and Austrian-allied Reichsarmee even more, and they gave up little information. Neither Saxe-Hildburghausen nor Soubise had an idea what Frederick intended, or indeed, what he was doing. Marshal Keith reached Merseburg and found the bridge there destroyed, with the Reichsarmee and French prepared to hold the other side of the river.[16] By the night of 3 November, Frederick's engineers finished their new bridges and the entire Prussian line advanced across the Saale.[11] As soon as Frederick had crossed the river, he sent 1,500 cavalry under the command of Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz to raid the Allied camp. He planned to attack it the next day, but the surprise raid frightened Soubise into moving during the night to a more secure position. On 4 November, Frederick moved to his camp at Rossbach.[11]

On the Allied side, the officers, both French and Austrian, were frustrated by their superiors' timidity. Clearly, Frederick's position was precarious, and the Prussians were outnumbered. One officer, Pierre-Joseph Bourcet, convinced Soubise that they should attack Frederick in the morning, by swinging to Frederick's left flank and cutting his line of retreat. This would, Bourcet thought, finish the campaign. After some persuasion Soubise and Saxe-Hildburghausen were convinced and everyone went to sleep. In the morning of 5 November, some of the Allied troops went out to forage, and Soubise received a notice from Saxe-Hildburghausen, something to the effect of not a moment to be lost, we should advance, gain the heights and attack from the side. Until that point, Soubise had done nothing to rouse the French troops to action.[11]

Battle

Initial battlefield dispositions

On the morning of 5 November 1757 the Prussian camp lay between Rossbach on the left and the village of Bedra on the right, facing the Allies. Charles, the Prince Soubise, commanding the French, and the Prince Saxe-Hildburghausen, commanding the Holy Roman Empire's forces, had maneuvered in the preceding days without giving Frederick an opportunity to begin fighting. Their forces were located to the west, with their right flank near the town of Branderoda and their left at Mücheln. The advanced posts of the Prussians stood in villages immediately west of their camp, those of the Allies on the Schortau hill and the Galgenberg.[17]

The Allies possessed a numerical superiority of two to one, and their advanced post, commanded by Claude Louis, Comte de Saint-Germain, overlooked all parts of Frederick's camp. The French and Habsburg Imperial (Reichsarmee) troops consisted of 62 battalions (31,000 infantry), 84 squadrons (10,000) of cavalry, and 109 artillery, totaling some 41–42,000 men, under Soubise's and Saxe-Hildburghausen's command.[18] The Allies had taken the lead in the maneuvers of the previous days, and Saxe-Hildburghausen decided to take the offensive. He had some difficulty inducing Soubise to risk a battle, so the Allies did not begin to move from their campground until after eleven a.m. on 5 November. Soubise probably intended to engage as late in the day as possible, with the idea of gaining what advantages he could in a partial action before nightfall. Their plan called for the Allied army to march by Zeuchfeld, around Frederick's left, which no serious natural obstacle covered, and to deploy in battle array facing north, between Reichardtswerben on the right and Pettstädt on the left. Saxe-Hildburghausen's proposed battle and the more limited aim of Soubise appeared equally likely to succeed by taking this position, which threatened to cut Frederick off from a retreat to the towns on the Saale. The Allies could attain this position only by marching around the Prussian flank, which could put them in the tenuous position of marching across their enemies' front. Consequently, the Allies posted a sizable guard against the obvious risk of interference on their exposed flank.[17]

On the other side, Frederick commanded 27 battalions of infantry (17,000 men) and 43 squadrons of cavalry (5,000 horse), plus 72 companies of artillery, for a total of 22,000 men.[18] He also had several of the siege guns from Leipzig, which arrived late in the morning. He spent the morning watching the French from the Goldacker manor rooftop in Rossbach. The initial stages of Allied movement convinced him that the Allies had started retreating southward towards their magazines; he sent out patrols to learn from the peasants what could be gleaned. They reported back that Soubise had taken the Weissenfels road; it led not only to that village, but also toward Freiburg, where Soubise could find supplies, or to Merseburg, where they would cut the Prussians off from the Saale. At about noon Frederick went to dinner, leaving the young captain Friedrich Wilhelm von Gaudi to observe French movements. Two hours later, his watch captain reported the French approaching. Although Gaudi's excited report at first appeared to confirm a French-Reichsarmee retreat, Frederick observed that Allied columns, which from time to time became visible in the undulations of the ground, appeared to turn eastwards from Zeuchfeld. When Frederick saw for himself that hostile cavalry and infantry were already approaching Pettstädt, he realized his enemy's intentions: to attack him in the flank and rear, and break his communications line, if not crush him completely. They now offered him the battle for which he had maneuvered in vain, and he accepted it without hesitation.[17]

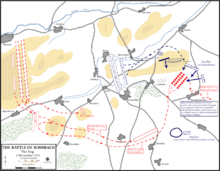

Opening moves

Frederick realized the gambit by 2:30 pm. By 3:00 pm, the entire Prussian army had struck camp, loaded their tents and gear, and fallen into line. Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz took his 38 squadrons of cavalry and moved toward the Janus and Pölzen, small hills between Rossbach and Reichardtswerben. Except for a few moments, the advance was hidden entirely from view. He was followed by Colonel Karl Friedrich von Moller's battery of 18 guns, which positioned themselves temporarily on the reverse of the Janus between the infantry's left and the cavalry's right. Seven squadrons remained in Rossbach to contain Saint-Germain's advanced post.[17]

Although aware of some of these movements, Soubise thought the Prussians were in full retreat. He ordered his advanced guard to hasten toward the Janus hill, but he issued no instructions on where, how and when to deploy. The Allied infantry moved in three long columns: at the head were the French regiments of Piedmont and Mailly, and on the flanks and in front of the right column were two regiments of Austrian cuirassiers and the Imperial cavalry. Ten French squadrons remained in reserve and twelve others protected the left flank. Soubise, who undoubtedly knew better, ordered no ground reconnaissance and sent no advanced guard. His army marched blindly into Frederick's clutches.[17]

Trap

When the Prussians broke camp, they left a handful of light troops to demonstrate before the French advance post commanded by the Comte de Saint-Germain. These light troops constituted the flank guard on the Schartau hill, which lay at right angles to the Janus and Pölzen. Frederick had no intention of either forming a line parallel to the enemy or of retreating. His army could move as a unit twice as fast as the Allies' army. If, at the moment of contact, the Allies had already formed their line of battle facing north, then his attack would strike their right flank; if they were still on the move in columns eastwards or northeastwards, the heads of their columns would be crushed before the rest could deploy in the new direction, deployment being a lengthy affair for most armies.[19]

The Allies marched in normal order in two main columns, the first line on the left, the second line on the right; farther to the right, though, marched a column consisting of the foot reserve, and between the first and second lines trundled the reserve artillery. The right wing cavalry advanced at the head and the left wing cavalry at the tail of the two main columns. Noting some Prussian movement, Soubise ordered a wheeling pivot to the east,[20] a complicated maneuver under parade-ground conditions, and difficult in the field, with troops unfamiliar with each other, on uneven terrain. At first, the columns retained regulation distance, wheeling eastward toward Zeuchfeld, but then part of the reserve infantry moved between the two main columns, hampering the movements of the reserve artillery. In addition, the troops on the outer flank of the wheel found themselves unable to keep up with the overly rapid movement of the inner pivot.[19]

Soubise and Saxe-Hildburghausen ignored the confusion as their own troops struggled in the wheeling pivot. From their vantage point, it appeared to the Allied commanders that the Prussians were moving eastward; Soubise and Saxe-Hildburghausen presumed that the Prussians were about to retreat in order to avoid being taken in their flank and rear. The Allied generals hurried the march, sending on the leading (right wing) cavalry towards Reichardtswerben. They also called up part of the left wing cavalry from the tail of the column and even the flank guard cavalry to take part in what they presumed would be the general chase. Any semblance of the wheeling pivot was lost in these fresh maneuvers, and the remaining columns lost all cohesion and order.[19]

Moller's artillery on Janus hill again opened fire on this confusion of men and horses at 3:15 pm. When they came under the fire of Moller's guns, the Allied cavalry, which now lay north of Reichardtswerben and well ahead of their own infantry, suffered from the barrage, but the commanders were not particularly concerned about the display of cannon fire. It was usual to employ heavy guns to protect a retreat, so the Allies assured themselves that Frederick was retreating and contented themselves with bringing some of their field guns into action. The cavalry hurried to get themselves out of range, but this further disorganized the Allied infantry lines, and caused any remaining unit cohesion to break down.[19]

Unseen by the Allies, Seydlitz assembled his cavalry into two lines, one of 20 squadrons and the second of 18, and reduced the speed of his approach until they reached the screening ridge of the Pölzen hill. There, they waited. Seydlitz sat at the head of the lines, calmly smoking his pipe. When the Allied cavalry came within striking distance, 1000 paces from the crest of the ridge, he tossed his pipe in the air: this was the signal to charge. At 3:30 pm, Seydlitz crested the hill and his first 20 squadrons descended on the Allied army; the leading Allied cuirassiers managed to deploy to meet Seydlitz's squadrons, but the momentum of the Prussian attack penetrated the Allied lines and wrought havoc among the disorganized mass. Prussian cavalry rode flank to flank; their training had taught them to form a line three and four deep from a column without breaking pace; once formed into a line, the troopers rode with knees touching, the horses' flanks touching, and horses riding tail to nose. Any attack of Prussian cavalry on open ground meant a line of horses—big Trakehners[Note 2]—bearing down on infantry or cavalry columns, lines, or squares. The horsemen could maneuver at a full gallop, to the left or right, or in an oblique.[19]

The fighting soon devolved into man-on-man combat; Seydlitz himself fought like a trooper, receiving a severe wound. He ordered his last 18 squadrons, still waiting at the Janus, into the fray. The second charge struck the French cavalry at an oblique angle. The mêlée drifted rapidly southward, past the Allied infantry. Part of the Allied reserve, which had become entangled between the main columns, was extricating itself by degrees and endeavoring to catch up with the rest of the reserve column away to the right, but the sweep of horses and Allied infantry pulled them into the fighting. The Allied reserve artillery proved useless; caught in the middle of the infantry columns, it could not deploy to support any of the endangered Allied troops. The Prussian infantry on the Shartau hill waited in echelon from the left. Those Allied units who escaped the artillery and the horsemen ran headlong into a hail of musket fire from Prince Henry's infantry.[19] Attempted French counterattacks dissolved into confusion. Most of the Allied cavalry units in front were smashed by the initial charge and many of them trampled over their own men trying to flee. The field was littered with riderless horses and horseless men, wounded, dying and dead. This part of the action took about 30 minutes.[22]

Seydlitz recalled his cavalry. This in itself was unusual: normally, a cavalry attacked once, maybe twice, and spent the rest of the battle chasing fleeing troops. Seydlitz led his rallied force toward the flank and rear of the Allied army, about 2 km (1 mi) out of the fighting and into a copse of trees between Reichardtswerben and Obschutz. There, horses and men could catch their breath. The Allies, relieved to see the last of the horsemen, became preoccupied with the Prussian infantry, about four battalions of it, threatening in linear formation to their left. Instead of forming into a similar line of attack, though, the Allied battalions formed into columns, fixed their bayonets and marched forward, prepared for a charge.[23]

As the Allies advanced, not yet in bayonet range, they came within range of Prince Henry's infantry; disciplined Prussian volleys shredded the orderly Allied columns. Then Moller's artillery, reinforced by siege guns from Leipzig, tore some additional gaps. The leading ranks faltered; the following ranks crowded into them, goaded on by their officers. Prince Henry's infantry advanced, still firing. Finally, seemingly out of nowhere, Seydlitz brought his cavalry in a flanking attack, this time all 38 squadrons in a massed attack; their sudden and energetic appearance at the flank and rear caused havoc and despair among the already demoralized Reichsarmee units assembled there. Three regiments of Franconian Imperial troops threw aside their muskets and ran, and the French ran with them. Seydlitz's troopers pursued and cut down the fleeing Allies until darkness made the chase impossible.[24]

Aftermath

The battle had lasted less than 90 minutes and the last episode of the infantry fight no more than fifteen minutes. Only seven Prussian battalions had engaged with the enemy, and these had expended five to fifteen rounds per man.[19]

Soubise and Saxe-Hildburghausen, who had been wounded, succeeded in keeping one or two regiments together, but the rest scattered over the countryside. The French and Imperial troops lost six generals, an unusually high count in eighteenth century warfare, although not surprising given the emphasis on cavalry action in this battle. Among the French and German Imperial troops, the Austrian demographer Gaston Bodart counted 1,000 dead (including six generals) and approximately 3,500 wounded (including four generals),[Note 3] for a total of 8.3% wounded or dead, and 12.2% (approximately 5,000) missing or captured. Other historians might place the numbers of captured higher, at almost one third, or about 13,800.[26] The Prussians took as trophies 72 cannons (62% of the Allied artillery), seven flags, and 21 standards.[18] The Prussians captured eight French generals and 260 officers.[27]

Prussian losses are more controversial: Frederick boasted of negligible casualties. In his thorough study of regimental histories, Bodart counted 169–170 Prussian dead (including seven officers), and 430 wounded (including Prince Henry, Seydlitz and two other generals, and 19 officers), or about 2.4% of the total Prussian force; these casualties amount to less than 10% of the engaged Prussian force. Other recent sources agree that the Prussians lost as few as 300 and as many as 500 among the wounded. In an assessment of surviving regimental records, modern sources place Prussian losses at even fewer than Bodart did: one colonel was killed, plus two other officers, and 67 soldiers.[27]

Soubise has historically taken the blame for the loss, but this may be an unfair assessment. While he did owe his rank to his good relationship with Madame de Pompadour, the mistress of King Louis XV, he was neither blessed with extraordinary military acumen nor with the best troops: he could do nothing about the former, and most of the latter were with Louis Charles César Le Tellier, fighting in the Rhineland. Under Soubise's command, the French had conducted a notorious march across Germany, characterized by persistent pillaging. His army also had approximately 12,000 civilian camp followers. There were chefs, hair dressers, perruquiers, barbers, wives and mistresses, pastry chefs, tailors and clothiers of all kinds, saddle makers, bridle makers, grooms, and servants of all varieties who served the nobility. In addition, the army had its usual motley crew of farriers, grooms, veterinarians, surgeons, and cooks that sustained an army on the march. After the battle, the Comte de Saint-Germain, who had commanded the advanced guard and also the rear guard that struggled to keep up with the fleeing army, complained that the troops in his charge had been defective, a gang of robbers, murderers, and cowards who ran at the sound of a gunshot.[28]

The Imperial army, although smaller, was not much better, and certainly not the battle-hardened army the Prussians had faced at Kolin. This was the Reichsarmee, an army consisting of units sent by the constituent members of the Holy Roman Empire. Their commander had reported that they were defective in training, administration, armaments, discipline and leadership. The same might be said of their commander, Saxe-Hildburghausen, an indolent and slow-moving man. The Imperial regimental officers often lacked even basic garrison training. These units had little experience working together, much less fighting together, a problem that expressed itself most evidently in the disastrous wheeling pivot. Furthermore, the Reichsarmee contingents came from many principalities, some of which were Protestant, and many of which were unhappy about any alliance with the French; most were more adverse to the French than they were to the Prussians.[29] Once news of the battle's uneven resolution spread, some Germans felt satisfaction; the battle could be seen as retribution for the years of suffering under the French atrocities in the Rhineland and Palatinate during the Palatinate campaign and the subsequent invasions and occupation of Louis XIV. Mostly, though, Rossbach was significant for the strengthening of Prussia's relationship with Frederick's uncle, King George, and George's other subjects. The British could now see the advantage of keeping the French occupied on the Continent while they continued their offensives against French territories in North America.[30]

While Frederick was engaging the combined Allied forces further west, that autumn the Austrians had slowly retaken Silesia: Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine had captured the city of Schweidnitz and moved on Breslau in lower Silesia. While heading back to Silesia, Frederick learned of the fall of Breslau (22 November). He and his 22,000 men reversed tracks, and covered 274 km (170 mi) from Rossbach to Leuthen (now Lutynia, Poland), 27 km (17 mi) west of Breslau in twelve days. On the way, at Liegnitz, they joined with the Prussian troops who had survived the fighting at Breslau. The augmented army of about 33,000 troops arrived at Leuthen to find 66,000 Austrians in possession. Despite his troops' exhaustion from the rapid march from Rossbach, Frederick won yet another decisive victory at Leuthen.[31]

Assessment

After the battle, Frederick reportedly said: "I won the battle of Rossbach with most of my infantry having their muskets shouldered." This was indeed true: less than twenty-five percent of his entire force had been engaged. Frederick had discovered the use of operational maneuvers and with a fraction of his entire force—3,500 horsemen, 18 artillery pieces, and three battalions of infantry—had defeated an army of two of the strongest European powers. Frederick's tactics at Rossbach became a landmark in the history of the military arts.[32]

Rossbach also highlighted the extraordinary talents of two of Frederick's officers, the artillery colonel Karl Friedrich von Moller and his cavalry general, Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz. Both men possessed the much-coveted coup d'œil militaire, the ability to discern at one glance the tactical advantages and disadvantages of the terrain. This attribute allowed them to use the artillery and cavalry to full potential.[33] Frederick himself called this "[T]he perfection of that art to learn at one just and determined view the benefits and disadvantages of a country where posts are to be placed and how to act upon the annoyance of the enemy. This is, in a word, the true meaning of a coup d'œil, without which an officer may commit errors of the greatest consequence."[34] On the morning of the battle Frederick had passed over two senior generals and placed Seydlitz in command of the whole of his cavalry, much to those men's annoyance and to Seydlitz' satisfaction. Seydlitz had spent the interim of the peace (1748–1756) training the cavalry to perform at optimum speed and force. The other outstanding officer, Colonel Moller, had invested the interim in developing a highly mobile artillery force. His artillery engineers were trained similarly to dragoons, to ride to a battle and fight dismounted; in the case of the artillery, they dragged their guns around the battlefield as needed. This was not yet the flying artillery that Frederick developed later, but it was similar in structure and function. Later developments refined the training and usage.[19]

Furthermore, the battle was one instance in which Moller's and Seydlitz's awareness of Frederick's operational objectives led to battlefield success. For example, not content with the single attack and recall, the coup de main, Seydlitz withdrew his squadrons into a copse, where they regrouped under cover of the trees. When the moment was right, he led his cavalry forward again in the coup de grâce, the finishing blow. Similarly, Moller's artillery waited on the reverse angle of the hill until the French were in range, then mounted the Janus and laid down a thorough and precise pattern of artillery fire; the concussion of Moller's thorough cannonade could be felt several miles away. Rossbach proved that the column as a means of tactical deployment on battlefield was inferior to the Prussian battle line; the massed columns simply could not hold in the face of either Moller's fire or Seydlitz's cavalry charges. The greater the formation of men, the greater the loss of life and limb.[19]

The stunning victory at the Battle of Rossbach marked a turning point in alliances of the Seven Years' War. Britain increased its financial support for Frederick.[35] French interest in the so-called Prussian war declined sharply after the Rossbach debacle and, with the signing of the Third Treaty of Versailles in March 1759, France reduced its financial and military contributions to the Coalition, leaving Austria on its own to deal with Prussia in Central Europe.[36] The French continued their campaign against Hanover and Prussia's Rhineland territories, but the Army of Hanover- commanded by one of Frederick's finest officers, Ferdinand of Brunswick- kept them tied down in western Germany for the rest of the war.

Battlefield today

From 1865 to 1990, the area was mined for lignite. The extensive open-cast mining operations caused fundamental changes in the landscape and the population: a total of 18 settlements and some 12,500 people were resettled over the time of the mining and manufacturing. Residents of Rossbach itself were resettled in 1963 and most of the town was destroyed by mining operations that same year. Today, most of the battlefield is covered in some farmland, vineyards and a nature park created from flooding the old lignite mine with water; the resulting lake has a surface area of 18.4 km2 (7 sq mi); at its deepest point, the lake is 78 m (256 ft) deep. In the course of filling the old pit, archaeologists found fossils 251–243 million years old.[37]

Four separate monuments dedicated to the battle were erected in the town of Reichardtswerben. The first monument was erected 16 September 1766, in gratitude to God for sparing the town of Reichardtswerben during the battle. The stone at Burgwerben castle was erected 9 July 1844, and bears the following inscription:

Before the Battle of Rossbach, on 5 November 1757, Joseph Marie Friedrich Wilhelm Hollandius, Prinz von Sachsen-Hildburghausen, commandant of the German Reichsarmee in the Seven Years' War, established his headquarters in this castle. From this location, he gave the order on 31 October 1757 to burn the Saale bridge at Weissenfels.

After the Battle of Rossbach on 5 November 1757, at six o'clock in the evening, the King of Prussia Frederick II, the Great, with only a small entourage, arrived at the castle. All rooms were occupied by wounded officers. His Majesty would not allow any of the [wounded] officers to be disturbed, and set up his field bed in an alcove and, after giving the orders for the day, spent the night there. The present owner was Superintendent Funcke; his grandson, Hauptmann [Franz Leopold] von Funcke, organized this in his memory.

Schloss Burgwerben the 9 July 1844, Franz Leopold v. Funcke.[38]

K2169, the county highway passing through Reichardtswerben, is named Von-Seydlitz-Straße.[39]

- Memorials

- Monument at Reichardtswerben

- Monument at Rossbach

Burgwerben Memorial

Burgwerben Memorial

- Battlefield over time

In 1903, the Imperial Army conducted maneuvers on part of the old battlefield.

In 1903, the Imperial Army conducted maneuvers on part of the old battlefield.

Panorama of the principal location of the battle today; the old pit mine was flooded, creating the Geiseltal See, now a swimming and recreation area.

Panorama of the principal location of the battle today; the old pit mine was flooded, creating the Geiseltal See, now a swimming and recreation area..jpg) Panorama of the principal location of the battle today

Panorama of the principal location of the battle today

Notes and citations

Notes

- Mayr's Freibatallion included approximately 1,500 infantry, hussars, some dragoons, and several pieces of light artillery. The Freibatallion was neither free nor a battalion; such formations were, at the time, comparable to what the privateer was in a navy. They operated outside the normal channels of military organization.[15]

- Most of Seydlitz's dragoons and hussars rode Trakehners. The modern Trakehner is 16–17 hands at the withers, or 162–168 cm (64–66 in).[21]

- According to Bodart, the fallen French generals included (1) the Comte de Durfort de Lorges; (2) Philippe-Joseph, the Comte de Custine (father of the French Revolutionary Wars general Adam Philippe, Comte de Custine); (3) the Comte de Doyat; (4) Michel du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (the father of Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette—Lafayette's father occasionally is identified as among the dead at the Battle of Minden in 1759, but Gaston Bodart places him at Rossbach); (5) the Comte de Revel; and (6) the Brigadier Paul, Duke Beauvilliers.[25]

Citations

- Peter H. Wilson, The Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire. Penguin, 2016, pp. 478–79.

- D.B. Horn, "The Diplomatic Revolution" in J. O. Lindsay, ed., The New Cambridge Modern History vol. 7, The Old Regime: 1713–63 (1957): pp. 449–64; Jeremy Black, Essay and Reflection: On the 'Old System' and the Diplomatic Revolution' of the Eighteenth Century, International History Review (1990) 12:2 pp. 301–23.

- Fred Anderson, Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2007, p. 302.

- Tim Blanning, Frederick the Great: King of Prussia. Random House Publishing Group, 2016, p. 232.

- Robert B. Asprey, Frederick the Great: The Magnificent Enigma. Ticknor & Fields, 1986, p. 460.

- Daniel Marston, The Seven Years' War, London; Osprey, 2001, p. 22.

- David Stone, A Military History of Russia: From Ivan the Terrible to the War in Chechnya, New York; Praeger, 2006, p.70

- Anderson, p. 176.

- Anderson, p. 302.

- Marston, p. 41.

- J. F. C. Fuller, A Military History of The Western World, Vol. II: From the Defeat of the Spanish Armada to the Battle Of Waterloo, Da Capo Press, 1987 pp. 202–03.

- The elevation of Rossbach is 124 meters (407 ft). Braunsbedra and Reichardtswerben are the two closest villages, and their elevations above sea level are 120 meters (394 ft) and 131 meters (430 ft) respectively. Flood Maps of Germany. Elevation of Braunsbedra, German flood maps. 2014. Accessed 16 August 2017.

- Herbert J. Redman,Frederick the Great and the Seven Years' War, 1756–1763. McFarland. 2015, p. 123.

- (in German) Gaston Bodart, Militär-historisches Kriegs-Lexikon, (1618–1905). Vienna, Stern, 1908, p. 220.

- Friedrich Kapp, George Bancroft, The Life of F. W. Von Steuben ... with an Introduction by G. Bancroft, 1859, p. 55, and Bernhard von Poten, Mayer, Johann von, Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie, Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Band 21 (1885), S. 108–09.

- Redman, pp. 123–24.

- Fuller, pp. 203–06.

- (in German) Bodart, p. 220.

- Redman, pp. 130–36.

- Charles Hastings Collette, The Handy Book of Company Drill and Practical Instructor, Etc, Houlston & Wright, 1862, pp. 227–33.

- American Trakehner Association, Breed characteristics and Dr. Robert Baird, M.D., "Sport Horse Conformation" (1st Edition, 1997), The American Trakehner Association, 19 August 2017.

- Dennis E. Showalter, Frederick the Great: A Military History. Frontline Books, 2012, p. 188.

- Showalter, p. 190; Redman, pp. 130–36.

- Showalter, p. 190.

- (in German) Bodart, p. 220

- Daniel Baugh, The Global Seven Years War 1754–1763, Routledge, 2014, p. 275.

- Blanning, p. 236.

- Blanning, p. 237; Showalter, p. 183.

- Blanning, p. 237; Showalter, pp. 183–85.

- Showalter, p. 192.

- Spencer C. Tucker, Battles that Changed History: an Encyclopedia of World Conflict. ABC-CLIO, 2010. pp. 233–35.

- Russell F. Weigley, The Age of Battles: The Quest for Decisive Warfare from Breitenfeld to Waterloo, Indiana University Press, 2004, p. 185.

- Robert Neville Lawley, General Seydlitz, a Military Biography. W. Clowes & Sons, 1852, pp. 10–14; Bernhard von Poten, Moller, Karl Friedrich von, Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie, Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften [Historical Commission at the Bavarian Academy of Sciences], Band 22 (1885), S. 127–28.

- Frederick, King of Prussia. Article 16, Particular Instructions, T. Egerton, Military Library, 1824.

- Friedrich Kohlrausch, A History of Germany: From the Earliest Period to the Present Time, Chapman and Hall, 1844, p. 577.

- Christopher Clark, Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600–1947. Penguin Books Limited, 2000, pp. 254–55.

- (in German) Mitteldeutsche Zeitung Ein Trio feiert das Flutungsende 30. April 2011, Zugriff am 1. September 2011 (digital version Archived 2010-02-28 at the Wayback Machine); Hellmund Meinolf (Hrsg.): "Das Geiseltal-Projekt 2000. Erste wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse." Hallesches Jahrbuch für Geowissenschaften Beiheft 13, Halle/S. 2001; and Karlheinz Fischer, "Die Waldelefanten von Neumark-Nord und Gröbern," Dietrich Mania (Hrsg.). Neumark-Nord – Ein interglaziales Ökosystem des mittelpaläolithischen Menschen. Veröffentlichungen des Landesmuseums für Vorgeschichte in Halle (62), Halle/Saale 2010, S. 361–37.

- (in German) Village of Burgwerben. Geschichte (History) Archived 2017-08-15 at the Wayback Machine. "Schloss Burgwerben ". Accessed 30 May 2017.

- Google Maps. Seydlitz Strasse in Reichardtswerben. Accessed 17 April 2017.

Resources

- American Trakehner Association, Breed characteristics. 1998. Accessed 19 August 2017.

- Anderson, Fred. Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2007 ISBN 978-0-3074-2539-3

- Asprey, Robert B. Frederick the Great: The Magnificent Enigma. Ticknor & Fields, 1986 ISBN 978-0-89919-352-6.

- Baird, Robert (MD), "Sport Horse Conformation" (1st Edition, 1997), The American Trakehner Association, Accessed 19 August 2017.

- Baugh, Daniel. The Global Seven Years' War 1754–1763. Routledge, 2014 ISBN 978-1-1381-7111-4

- Black, Jeremy. Essay and Reflection: On the 'Old System' and the Diplomatic Revolution' of the Eighteenth Century. International History Review (1990) 12:2 pp. 301–23 ISSN 0707-5332

- Blanning, Tim. Frederick the Great: King of Prussia. Random House Publishing Group, 2016 ISBN 978-0-8129-8873-4.

- (in German) Burgwerben. Geschichte. Burgwerben Weindorf (website). Schloss Burgwerben. Accessed 30 May 2017.

- (in German) Bodart, Gaston. Militär-historisches Kriegs-Lexikon, (1618–1905). Stern, 1908 OCLC 799884224

- Clark, Christopher. Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600–1947. Penguin Books Limited, 2000, ISBN 978-0-6740-3196-8

- Collette, Charles Hastings. The Handy Book of Company Drill and Practical Instructor, Etc Houlston & Wright, 1862 OCLC 558127476

- Flood Maps of Germany. Elevation of Braunsbedra, German flood maps. 2014. Accessed 16 August 2017.

- Frederick, King of Prussia. Particular Instructions, Article 16. T. Egerton, Military Library, 1824 OCLC 17329080

- Fuller, J. F. C. A Military History Of The Western World, Vol. II: From The Defeat Of The Spanish Armada To The Battle Of Waterloo, Da Capo Press, 1987, ISBN 978-0-3068-03055.

- (in German) Hand, Karlheinz Fischer. "Die Waldelefanten von Neumark-Nord und Gröbern." In Dietrich Mania (Hrsg.). Neumark-Nord – Ein interglaziales Ökosystem des mittelpaläolithischen Menschen. Veröffentlichungen des Landesmuseums für Vorgeschichte in Halle (62), Halle/Saale 2010, S. 361–37, ISBN 9783939414377.

- Horn, D.B. "The Diplomatic Revolution" in J. O. Lindsay, ed., The New Cambridge Modern History vol. 7, The Old Regime: 1713–63 (1957): pp. 449–64, ISBN 978-0-5114-69008.

- Kapp, Friedrich, George Bancroft. The Life of F. W. Von Steuben ... with an Introduction by G. Bancroft, 1859 OCLC 560546360

- Kohlrausch, Friedrich. A History of Germany: From the Earliest Period to the Present Time, Chapman and Hall, 1844 OCLC 610585185

- Lawley, Robert Neville. General Seydlitz, a Military Biography. W. Clowes & Sons, 1852.

- Marston, Daniel. The Seven Years' War, Osprey, 2001, ISBN 978-1-4728-0992-6.

- (in German) Meinolf, Hellmund (Hrsg.) "Das Geiseltal-Projekt 2000. Erste wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse." Hallesches Jahrbuch für Geowissenschaften, Beiheft 13, Halle, 2001, ISSN 1432-3702.

- (in German) Mitteldeutsche Zeitung. "Ein Trio feiert das Flutungsende." 30. April 2011, Zugriff am 1. September 2011 (digital version Archived 2010-02-28 at the Wayback Machine).

- Poten, Bernhard von. Mayer, Johann von, Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie. Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Band 21 (1885), S. 108–09.

- Poten, Bernhard von. Moller, Karl Friedrich von, Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie. Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Band 22 (1885), S. 127–28.

- Redman, Herbert J. Frederick the Great and the Seven Years' War, 1756–1763. McFarland, 2015 ISBN 978-0-7864-7669-5.

- Showalter, Dennis E. Frederick the Great: A Military History. Frontline Books, 2012 ISBN 978-1-78303-479-6.

- Stone, David. A Military History of Russia: From Ivan the Terrible to the War in Chechnya, Praeger, 2006 ISBN 978-0-2759-8502-8

- Tucker, Spencer. Battles that Changed History: an Encyclopedia of World Conflict. ABC-CLIO, 2010, ISBN 978-1-5988-4429-0

- Weigley, Russell. The Age of Battles: The Quest for Decisive Warfare from Breitenfeld to Waterloo, Indiana University Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0-2532-1707-3.

- Wilson, Peter H. The Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire. Penguin, 2016, ISBN 978-0-67405-8095.

Further reading

- Barrow, Stephen A. Death of a Nation: A New History of Germany. Book Guild Publishing, 2016 ISBN 978-1-910508-81-7

- Carlisle, Thomas. History of Friedrich II. of Prussia, Called Frederick the Great. Scribner, Welford, 1873, volume 29, chapter 4. OCLC 174919338

- Citino, Robert M. The German Way of War: from the Thirty Years War to the Third Reich, University Press of Kansas, 2005, ISBN 978-0-700616-24-4.

- (in French) Clark, Christopher. Histoire de la Prusse, Perrin, 2009 ISBN 978-2-262-04746-7

- Duffy, Christopher. The Military Life of Frederick the Great, Antheneum, 1986. ISBN 0-689-11548-2

- Jomini, General Baron Antoine Henri de. Treatise On Grand Military Operations: Or A Critical And Military History Of The Wars Of Frederick The Great. Pickle Partners Publishing, 2013, particularly volume 2, chapter XVII.

- Jones, Archer. The Art of War in the Western World. University of Illinois Press, 2001 ISBN 978-0-2520-6966-6

- Longman, Frederick William. Frederick the Great and the Seven Years' War. Longmans, Green, and Company, 1881 OCLC 253698521

- Millar, Simon. Rossbach and Leuthen 1757. Osprey Campaign Series vol. 113; Osprey Publishing, 2002 ISBN 978-1-8417-6509-9

- Napoleon I (Emperor of the French). Memoirs of the history of France during the reign of Napoleon. Historical miscellanies, dictated to the count de Montholon. 1823, particularly chapters 4–6.

- Nolan, Cathal. The Allure of Battle: A History of How Wars Have Been Won and Lost. Oxford University Press, 2017 ISBN 978-0-1999-1099-1