Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach[lower-alpha 1] (31 March [O.S. 21 March] 1685 – 28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the Baroque period. He is known for instrumental compositions such as the Brandenburg Concertos and the Goldberg Variations, and for vocal music such as the St Matthew Passion and the Mass in B minor. Since the 19th-century Bach Revival he has been generally regarded as one of the greatest composers of all time.[3][4]

Johann Sebastian Bach | |

|---|---|

Bach, 1746 | |

| Born | 21 March 1685 (O.S.) 31 March 1685 (N.S.) |

| Died | 28 July 1750 (aged 65) |

Works | List of compositions |

| Signature | |

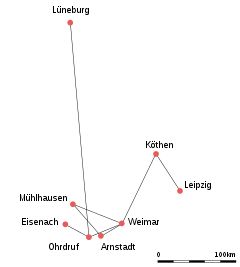

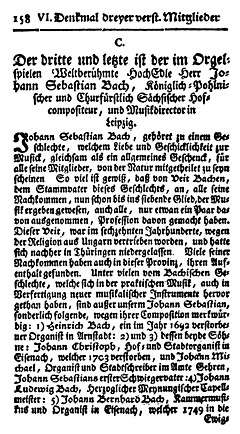

The Bach family already counted several composers when Johann Sebastian was born as the last child of a city musician in Eisenach. After being orphaned at age 10, he lived for five years with his eldest brother Johann Christoph, after which he continued his musical formation in Lüneburg. From 1703 he was back in Thuringia, working as a musician for Protestant churches in Arnstadt and Mühlhausen and, for longer stretches of time, at courts in Weimar, where he expanded his organ repertory, and Köthen, where he was mostly engaged with chamber music. From 1723 he was employed as Thomaskantor (cantor at St. Thomas) in Leipzig. He composed music for the principal Lutheran churches of the city, and for its university's student ensemble Collegium Musicum. From 1726 he published some of his keyboard and organ music. In Leipzig, as had happened during some of his earlier positions, he had difficult relations with his employer, a situation that was little remedied when he was granted the title of court composer by his sovereign, Augustus, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, in 1736. In the last decades of his life he reworked and extended many of his earlier compositions. He died of complications after eye surgery in 1750 at the age of 65.

Bach enriched established German styles through his mastery of counterpoint, harmonic and motivic organisation, and his adaptation of rhythms, forms, and textures from abroad, particularly from Italy and France. Bach's compositions include hundreds of cantatas, both sacred and secular. He composed Latin church music, Passions, oratorios, and motets. He often adopted Lutheran hymns, not only in his larger vocal works, but for instance also in his four-part chorales and his sacred songs. He wrote extensively for organ and for other keyboard instruments. He composed concertos, for instance for violin and for harpsichord, and suites, as chamber music as well as for orchestra. Many of his works employ the genres of canon and fugue.

Throughout the 18th century Bach was primarily valued as an organist, while his keyboard music, such as The Well-Tempered Clavier, was appreciated for its didactic qualities. The 19th century saw the publication of some major Bach biographies, and by the end of that century all of his known music had been printed. Dissemination of scholarship on the composer continued through periodicals (and later also websites) exclusively devoted to him, and other publications such as the Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis (BWV, a numbered catalogue of his works) and new critical editions of his compositions. His music was further popularised through a multitude of arrangements, including, for instance, the Air on the G String, and of recordings, such as three different box sets with complete performances of the composer's oeuvre marking the 250th anniversary of his death.

Life

Bach was born in 1685 in Eisenach, in the duchy of Saxe-Eisenach, into an extensive musical family. His father, Johann Ambrosius Bach, was the director of the town musicians, and all of his uncles were professional musicians. His father probably taught him to play the violin and harpsichord, and his brother Johann Christoph Bach taught him the clavichord and exposed him to much of the contemporary music.[5] Apparently on his own initiative, Bach attended St. Michael's School in Lüneburg for two years. After graduating, he held several musical posts across Germany, including Kapellmeister (director of music) to Leopold, Prince of Anhalt-Köthen, and Thomaskantor in Leipzig, a position of music director at the main Lutheran churches and educator at the Thomasschule. He received the title of "Royal Court Composer" from Augustus III in 1736.[6][7] Bach's health and vision declined in 1749, and he died on 28 July 1750.

Childhood (1685–1703)

Johann Sebastian Bach was born in Eisenach, the capital of the duchy of Saxe-Eisenach, in present-day Germany, on 21 March 1685 O.S. (31 March 1685 N.S.). He was the son of Johann Ambrosius Bach, the director of the town musicians, and Maria Elisabeth Lämmerhirt.[10] He was the eighth and youngest child of Johann Ambrosius,[11] who likely taught him violin and basic music theory.[12] His uncles were all professional musicians, whose posts included church organists, court chamber musicians, and composers. One uncle, Johann Christoph Bach (1645–1693), introduced him to the organ, and an older second cousin, Johann Ludwig Bach (1677–1731), was a well-known composer and violinist.[13]

Bach's mother died in 1694, and his father died eight months later.[7] The 10-year-old Bach moved in with his eldest brother, Johann Christoph Bach (1671–1721), the organist at St. Michael's Church in Ohrdruf, Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg.[14] There he studied, performed, and copied music, including his own brother's, despite being forbidden to do so because scores were so valuable and private, and blank ledger paper of that type was costly.[15][16] He received valuable teaching from his brother, who instructed him on the clavichord. J. C. Bach exposed him to the works of great composers of the day, including South German composers such as Johann Pachelbel (under whom Johann Christoph had studied) and Johann Jakob Froberger; North German composers;[5] Frenchmen, such as Jean-Baptiste Lully, Louis Marchand, and Marin Marais; and the Italian clavierist Girolamo Frescobaldi. Also during this time, he was taught theology, Latin, Greek, French, and Italian at the local gymnasium.[17]

By 3 April 1700, Bach and his schoolfriend Georg Erdmann—who was two years Bach's elder—were enrolled in the prestigious St. Michael's School in Lüneburg, some two weeks' travel north of Ohrdruf.[18][19] Their journey was probably undertaken mostly on foot.[17][19] His two years there were critical in exposing Bach to a wider range of European culture. In addition to singing in the choir, he played the school's three-manual organ and harpsichords.[17] He came into contact with sons of aristocrats from northern Germany who were sent to the highly selective school to prepare for careers in other disciplines.

While in Lüneburg, Bach had access to St. John's Church and possibly used the church's famous organ from 1553, since it was played by his organ teacher Georg Böhm.[20] Because of his musical talent, Bach had significant contact with Böhm while a student in Lüneburg, and he also took trips to nearby Hamburg where he observed "the great North German organist Johann Adam Reincken".[20][21] Stauffer reports the discovery in 2005 of the organ tablatures that Bach wrote, while still in his teens, of works by Reincken and Dieterich Buxtehude, showing "a disciplined, methodical, well-trained teenager deeply committed to learning his craft".[20]

Weimar, Arnstadt, and Mühlhausen (1703–1708)

In January 1703, shortly after graduating from St. Michael's and being turned down for the post of organist at Sangerhausen,[23] Bach was appointed court musician in the chapel of Duke Johann Ernst III in Weimar.[24] His role there is unclear, but it probably included menial, non-musical duties. During his seven-month tenure at Weimar, his reputation as a keyboardist spread so much that he was invited to inspect the new organ and give the inaugural recital at the New Church (now Bach Church) in Arnstadt, located about 30 kilometres (19 mi) southwest of Weimar.[25] In August 1703, he became the organist at the New Church,[26] with light duties, a relatively generous salary, and a new organ tuned in a temperament that allowed music written in a wider range of keys to be played.

Despite strong family connections and a musically enthusiastic employer, tension built up between Bach and the authorities after several years in the post. Bach was dissatisfied with the standard of singers in the choir. He called one of them a "Zippel Fagottist" (weenie bassoon player). Late one evening this student, named Geyersbach, went after Bach with a stick. Bach filed a complaint against Geyersbach with the authorities. They acquitted Geyersbach with a minor reprimand and ordered Bach to be more moderate regarding the musical qualities he expected from his students. Some months later Bach upset his employer by a prolonged absence from Arnstadt: after obtaining leave for four weeks, he was absent for around four months in 1705–1706 to visit the organist and composer Dieterich Buxtehude in the northern city of Lübeck. The visit to Buxtehude involved a 450-kilometre (280 mi) journey each way, reportedly on foot.[27][28]

In 1706, Bach applied for a post as organist at the Blasius Church in Mühlhausen.[29][30] As part of his application, he had a cantata performed on Easter, 24 April 1707, likely an early version of his Christ lag in Todes Banden.[31] A month later Bach's application was accepted and he took up the post in July.[29] The position included significantly higher remuneration, improved conditions, and a better choir. Four months after arriving at Mühlhausen, Bach married Maria Barbara Bach, his second cousin. Bach was able to convince the church and town government at Mühlhausen to fund an expensive renovation of the organ at the Blasius Church. In 1708 Bach wrote Gott ist mein König, a festive cantata for the inauguration of the new council, which was published at the council's expense.[17]

Return to Weimar (1708–1717)

Bach left Mühlhausen in 1708, returning to Weimar this time as organist and from 1714 Konzertmeister (director of music) at the ducal court, where he had an opportunity to work with a large, well-funded contingent of professional musicians.[17] Bach and his wife moved into a house close to the ducal palace.[32] Later the same year, their first child, Catharina Dorothea, was born, and Maria Barbara's elder, unmarried sister joined them. She remained to help run the household until her death in 1729. Three sons were also born in Weimar: Wilhelm Friedemann, Carl Philipp Emanuel, and Johann Gottfried Bernhard. Johann Sebastian and Maria Barbara had three more children, who however did not live to their first birthday, including twins born in 1713.[33]

Bach's time in Weimar was the start of a sustained period of composing keyboard and orchestral works. He attained the proficiency and confidence to extend the prevailing structures and include influences from abroad. He learned to write dramatic openings and employ the dynamic rhythms and harmonic schemes found in the music of Italians such as Vivaldi, Corelli, and Torelli. Bach absorbed these stylistic aspects in part by transcribing Vivaldi's string and wind concertos for harpsichord and organ; many of these transcribed works are still regularly performed. Bach was particularly attracted to the Italian style, in which one or more solo instruments alternate section-by-section with the full orchestra throughout a movement.[34]

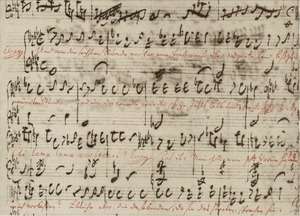

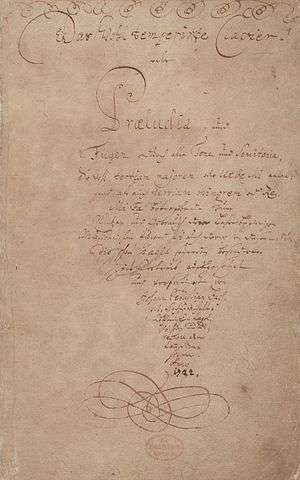

In Weimar, Bach continued to play and compose for the organ and perform concert music with the duke's ensemble.[17] He also began to write the preludes and fugues which were later assembled into his monumental work The Well-Tempered Clavier ("clavier" meaning clavichord or harpsichord),[35] consisting of two books,[36] each containing 24 preludes and fugues in every major and minor key. Bach also started work on the Little Organ Book in Weimar, containing traditional Lutheran chorale tunes set in complex textures. In 1713, Bach was offered a post in Halle when he advised the authorities during a renovation by Christoph Cuntzius of the main organ in the west gallery of the Market Church of Our Dear Lady.[37][38]

In the spring of 1714, Bach was promoted to Konzertmeister, an honour that entailed performing a church cantata monthly in the castle church.[39] The first three cantatas in the new series Bach composed in Weimar were Himmelskönig, sei willkommen, BWV 182, for Palm Sunday, which coincided with the Annunciation that year; Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen, BWV 12, for Jubilate Sunday; and Erschallet, ihr Lieder, erklinget, ihr Saiten! BWV 172 for Pentecost.[40] Bach's first Christmas cantata, Christen, ätzet diesen Tag, BWV 63, was premiered in 1714 or 1715.[41][42]

In 1717, Bach eventually fell out of favour in Weimar and, according to a translation of the court secretary's report, was jailed for almost a month before being unfavourably dismissed: "On November 6, [1717], the quondam concertmaster and organist Bach was confined to the County Judge's place of detention for too stubbornly forcing the issue of his dismissal and finally on December 2 was freed from arrest with notice of his unfavourable discharge."[43]

Köthen (1717–1723)

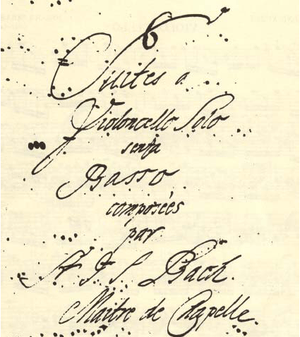

Leopold, Prince of Anhalt-Köthen, hired Bach to serve as his Kapellmeister (director of music) in 1717. Prince Leopold, himself a musician, appreciated Bach's talents, paid him well and gave him considerable latitude in composing and performing. The prince was a Calvinist and did not use elaborate music in his worship; accordingly, most of Bach's work from this period was secular,[44] including the orchestral suites, cello suites, sonatas and partitas for solo violin, and Brandenburg Concertos.[45] Bach also composed secular cantatas for the court, such as Die Zeit, die Tag und Jahre macht, BWV 134a. A significant influence upon Bach's musical development during his years with the prince is recorded by Stauffer as Bach's "complete embrace of dance music, perhaps the most important influence on his mature style other than his adoption of Vivaldi's music in Weimar."[20]

Despite being born in the same year and only about 130 kilometres (80 mi) apart, Bach and Handel never met. In 1719, Bach made the 35-kilometre (22 mi) journey from Köthen to Halle with the intention of meeting Handel; however, Handel had left the town.[46] In 1730, Bach's oldest son, Wilhelm Friedemann, travelled to Halle to invite Handel to visit the Bach family in Leipzig, but the visit did not take place.[47]

On 7 July 1720, while Bach was away in Carlsbad with Prince Leopold, Bach's wife suddenly died.[48] The following year, he met Anna Magdalena Wilcke, a young, highly gifted soprano 16 years his junior, who performed at the court in Köthen; they married on 3 December 1721.[49] Together they had 13 more children, 6 of whom survived into adulthood: Gottfried Heinrich; Elisabeth Juliane Friederica (1726–1781); Johann Christoph Friedrich and Johann Christian, who both, especially Johann Christian, became significant musicians; Johanna Carolina (1737–1781); and Regina Susanna (1742–1809).[50]

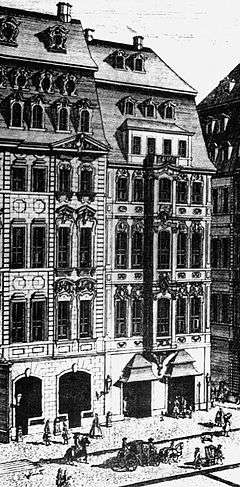

Leipzig (1723–1750)

In 1723, Bach was appointed Thomaskantor, Cantor of the Thomasschule at the Thomaskirche (St. Thomas Church) in Leipzig, which provided music for four churches in the city: the Thomaskirche and Nikolaikirche (St. Nicholas Church) and to a lesser extent the Neue Kirche (New Church) and Peterskirche (St. Peter's Church).[52] This was "the leading cantorate in Protestant Germany",[53] located in the mercantile city in the Electorate of Saxony, which he held for 27 years until his death. During that time he gained further prestige through honorary appointments at the courts of Köthen and Weissenfels, as well as that of the Elector Frederick Augustus (who was also King of Poland) in Dresden.[53] Bach frequently disagreed with his employer, Leipzig's city council, which he regarded as "penny-pinching".[54]

Appointment in Leipzig

Johann Kuhnau had been Thomaskantor in Leipzig from 1701 until his death on 5 June 1722. Bach had visited Leipzig during Kuhnau's tenure: in 1714 he attended the service at the St. Thomas Church on the first Sunday of Advent,[55] and in 1717 he had tested the organ of the Paulinerkirche.[56] In 1716 Bach and Kuhnau had met on the occasion of the testing and inauguration of an organ in Halle.[38]

After being offered the position, Bach was invited to Leipzig only after Georg Philipp Telemann indicated that he would not be interested in relocating to Leipzig.[57] Telemann went to Hamburg, where he "had his own struggles with the city's senate".[58]

Bach was required to instruct the students of the Thomasschule in singing and provide church music for the main churches in Leipzig. He was also assigned to teach Latin but was allowed to employ four "prefects" (deputies) to do this instead. The prefects also aided with musical instruction.[59] A cantata was required for the church services on Sundays and additional church holidays during the liturgical year.

Cantata cycle years (1723–1729)

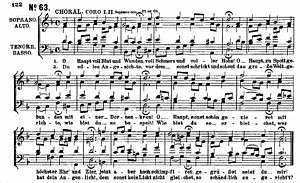

Bach usually led performances of his cantatas, most of which were composed within three years of his relocation to Leipzig. The first was Die Elenden sollen essen, BWV 75, performed in the Nikolaikirche on 30 May 1723, the first Sunday after Trinity. Bach collected his cantatas in annual cycles. Five are mentioned in obituaries, three are extant.[40] Of the more than 300 cantatas which Bach composed in Leipzig, over 100 have been lost to posterity.[60] Most of these works expound on the Gospel readings prescribed for every Sunday and feast day in the Lutheran year. Bach started a second annual cycle the first Sunday after Trinity of 1724 and composed only chorale cantatas, each based on a single church hymn. These include O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort, BWV 20, Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, BWV 140, Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, BWV 62, and Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern, BWV 1.

Bach drew the soprano and alto choristers from the school and the tenors and basses from the school and elsewhere in Leipzig. Performing at weddings and funerals provided extra income for these groups; it was probably for this purpose, and for in-school training, that he wrote at least six motets.[61] As part of his regular church work, he performed other composers' motets, which served as formal models for his own.[62]

Bach's predecessor as cantor, Johann Kuhnau, had also been music director for the Paulinerkirche, the church of Leipzig University. But when Bach was installed as cantor in 1723, he was put in charge only of music for festal (church holiday) services at the Paulinerkirche; his petition to also provide music for regular Sunday services there (for a corresponding salary increase) went all the way to the Elector but was denied. After this, in 1725, Bach "lost interest" in working even for festal services at the Paulinerkirche and appeared there only on "special occasions".[63] The Paulinerkirche had a much better and newer (1716) organ than did the Thomaskirche or the Nikolaikirche.[64] Bach was not required to play any organ in his official duties, but it is believed he liked to play on the Paulinerkirche organ "for his own pleasure".[65]

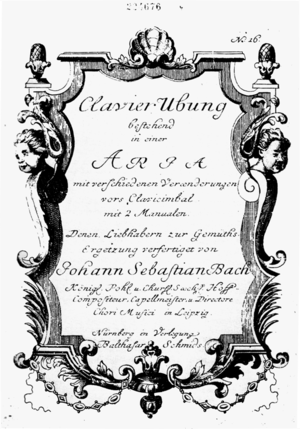

Bach broadened his composing and performing beyond the liturgy by taking over, in March 1729, the directorship of the Collegium Musicum, a secular performance ensemble started by Telemann. This was one of the dozens of private societies in the major German-speaking cities that were established by musically active university students; these societies had become increasingly important in public musical life and were typically led by the most prominent professionals in a city. In the words of Christoph Wolff, assuming the directorship was a shrewd move that "consolidated Bach's firm grip on Leipzig's principal musical institutions".[66] Year round, Leipzig's Collegium Musicum performed regularly in venues such as the Café Zimmermann, a coffeehouse on Catherine Street off the main market square. Many of Bach's works during the 1730s and 1740s were written for and performed by the Collegium Musicum; among these were parts of his Clavier-Übung (Keyboard Practice) and many of his violin and keyboard concertos.[17]

Middle years of the Leipzig period (1730–1739)

In 1733, Bach composed a Kyrie–Gloria Mass in B minor which he later incorporated in his Mass in B minor. He presented the manuscript to the Elector in an eventually successful bid to persuade the prince to give him the title of Court Composer.[6] He later extended this work into a full mass by adding a Credo, Sanctus, and Agnus Dei, the music for which was partly based on his own cantatas and partly original. Bach's appointment as Court Composer was an element of his long-term struggle to achieve greater bargaining power with the Leipzig council. Between 1737 and 1739, Bach's former pupil Carl Gotthelf Gerlach held the directorship of the Collegium Musicum.

In 1735 Bach started to prepare his first publication of organ music, which was printed as the third Clavier-Übung in 1739.[67] From around that year he started to compile and compose the set of preludes and fugues for harpsichord that would become his second book of The Well-Tempered Clavier.[68]

Final years and death (1740–1750)

From 1740 to 1748 Bach copied, transcribed, expanded or programmed music in an older polyphonic style (stile antico) by, among others, Palestrina (BNB I/P/2),[69] Kerll (BWV 241),[70] Torri (BWV Anh. 30),[71] Bassani (BWV 1081),[72] Gasparini (Missa Canonica)[73] and Caldara (BWV 1082).[74] Bach's own style shifted in the last decade of his life, showing an increased integration of polyphonic structures and canons and other elements of the stile antico.[75] His fourth and last Clavier-Übung volume, the Goldberg Variations, for two-manual harpsichord, contained nine canons and was published in 1741.[76] Throughout this period, Bach also continued to adopt music of contemporaries such as Handel (BNB I/K/2)[77] and Stölzel (BWV 200),[78] and gave many of his own earlier compositions, such as the St Matthew and St John Passions and the Great Eighteen Chorale Preludes,[79] their final revisions. He also programmed and adapted music by composers of a younger generation, including Pergolesi (BWV 1083)[80] and his own students such as Goldberg (BNB I/G/2).[81]

In 1746 Bach was preparing to enter Lorenz Christoph Mizler's Society of Musical Sciences.[82] In order to be admitted Bach had to submit a composition, for which he chose his Canonic Variations on "Vom Himmel hoch da komm' ich her", and a portrait, which was painted by Elias Gottlob Haussmann and featured Bach's Canon triplex á 6 Voc.[83] In May 1747, Bach visited the court of King Frederick II of Prussia in Potsdam. The king played a theme for Bach and challenged him to improvise a fugue based on his theme. Bach obliged, playing a three-part fugue on one of Frederick's fortepianos, which was a new type of instrument at the time. Upon his return to Leipzig he composed a set of fugues and canons, and a trio sonata, based on the Thema Regium (theme of the king). Within a few weeks this music was published as The Musical Offering and dedicated to Frederick. The Schübler Chorales, a set of six chorale preludes transcribed from cantata movements Bach had composed some two decades earlier, were published within a year.[84][85] Around the same time, the set of five canonic variations which Bach had submitted when entering Mizler's society in 1747 were also printed.[86]

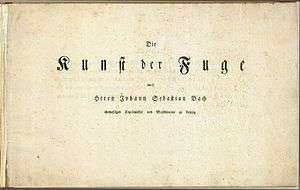

Two large-scale compositions occupied a central place in Bach's last years. From around 1742 he wrote and revised the various canons and fugues of The Art of Fugue, which he continued to prepare for publication until shortly before his death.[87][88] After extracting a cantata, BWV 191, from his 1733 Kyrie-Gloria Mass for the Dresden court in the mid 1740s, Bach expanded that setting into his Mass in B minor in the last years of his life. Stauffer describes it as "Bach's most universal church work. Consisting mainly of recycled movements from cantatas written over a thirty-five-year period, it allowed Bach to survey his vocal pieces one last time and pick select movements for further revision and refinement."[20] Although the complete mass was never performed during the composer's lifetime, it is considered to be among the greatest choral works in history.[89]

In January 1749, Bach's daughter Elisabeth Juliane Friederica married his pupil Johann Christoph Altnickol. Bach's health was, however, declining. On 2 June, Heinrich von Brühl wrote to one of the Leipzig burgomasters to request that his music director, Johann Gottlob Harrer, fill the Thomaskantor and Director musices posts "upon the eventual ... decease of Mr. Bach".[90] Becoming blind, Bach underwent eye surgery, in March 1750 and again in April, by the British eye surgeon John Taylor, a man widely understood today as a charlatan and believed to have blinded hundreds of people.[91] Bach died on 28 July 1750 from complications due to the unsuccessful treatment.[92][93][94] An inventory drawn up a few months after Bach's death shows that his estate included five harpsichords, two lute-harpsichords, three violins, three violas, two cellos, a viola da gamba, a lute and a spinet, along with 52 "sacred books", including works by Martin Luther and Josephus.[95] The composer's son Carl Philipp Emanuel saw to it that The Art of Fugue, although still unfinished, was published in 1751.[96] Together with one of the composer's former students, Johann Friedrich Agricola, the son also wrote the obituary ("Nekrolog"), which was published in Mizler's Musikalische Bibliothek, the organ of the Society of Musical Sciences, in 1754.[97]

Musical style

From an early age, Bach studied the works of his musical contemporaries of the Baroque period and those of prior generations, and those influences were reflected in his music.[98] Like his contemporaries Handel, Telemann and Vivaldi, Bach composed concertos, suites, recitatives, da capo arias, and four-part choral music and employed basso continuo. Bach's music was harmonically more innovative than his peer composers, employing surprisingly dissonant chords and progressions, often with extensive exploration of harmonic possibilities within one piece.[99]

The hundreds of sacred works Bach created are usually seen as manifesting not just his craft but also a truly devout relationship with God.[100][101] He had taught Luther's Small Catechism as the Thomaskantor in Leipzig, and some of his pieces represent it.[102] The Lutheran chorale was the basis of much of his work. In elaborating these hymns into his chorale preludes, he wrote more cogent and tightly integrated works than most, even when they were massive and lengthy. The large-scale structure of every major Bach sacred vocal work is evidence of subtle, elaborate planning to create a religiously and musically powerful expression. For example, the St Matthew Passion, like other works of its kind, illustrated the Passion with Bible text reflected in recitatives, arias, choruses, and chorales, but in crafting this work, Bach created an overall experience that has been found over the intervening centuries to be both musically thrilling and spiritually profound.[103]

Bach published or carefully compiled in manuscript many collections of pieces that explored the range of artistic and technical possibilities inherent in almost every genre of his time except opera. For example, The Well-Tempered Clavier comprises two books, each of which presents a prelude and fugue in every major and minor key, displaying a dizzying variety of structural, contrapuntal and fugal techniques.[104]

Four-part harmony

Four-part harmonies predate Bach, but he lived during a time when modal music in Western tradition was largely supplanted in favour of the tonal system. In this system a piece of music progresses from one chord to the next according to certain rules, each chord being characterised by four notes. The principles of four-part harmony are found not only in Bach's four-part choral music: he also prescribes it for instance for the figured bass accompaniment.[105] The new system was at the core of Bach's style, and his compositions are to a large extent considered as laying down the rules for the evolving scheme that would dominate musical expression in the next centuries. Some examples of this characteristic of Bach's style and its influence:

- When in the 1740s Bach staged his arrangement of Pergolesi's Stabat Mater, he upgraded the viola part (which in the original composition plays in unison with the bass part) to fill out the harmony, thus adapting the composition to his four-part harmony style.[106]

- When, starting in the 19th century in Russia, there was a discussion about the authenticity of four-part court chant settings compared to earlier Russian traditions, Bach's four-part chorale settings, such as those ending his Chorale cantatas, were considered as foreign-influenced models. Such influence was deemed unavoidable, however.[107]

Bach's insistence on the tonal system and contribution to shaping it did not imply he was less at ease with the older modal system and the genres associated with it: more than his contemporaries (who had "moved on" to the tonal system without much exception), Bach often returned to the then-antiquated modi and genres. His Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue, emulating the chromatic fantasia genre as used by earlier composers such as Dowland and Sweelinck in D dorian mode (comparable to D minor in the tonal system), is an example of this.

Modulation

Modulation, or changing key in the course of a piece, is another style characteristic where Bach goes beyond what was usual in his time. Baroque instruments vastly limited modulation possibilities: keyboard instruments, prior to a workable system of temperament, limited the keys that could be modulated to, and wind instruments, especially brass instruments such as trumpets and horns, about a century before they were fitted with valves, were tied to the key of their tuning. Bach pushed the limits: he added "strange tones" in his organ playing, confusing the singing, according to an indictment he had to face in Arnstadt,[108] and Louis Marchand, another early experimenter with modulation, seems to have avoided confrontation with Bach because the latter went further than anyone had done before.[109] In the "Suscepit Israel" of his 1723 Magnificat, he had the trumpets in E-flat play a melody in the enharmonic scale of C minor.[110]

The major development taking place in Bach's time, and to which he contributed in no small way, was a temperament for keyboard instruments that allowed their use in all available keys (12 major and 12 minor) and also modulation without retuning. His Capriccio on the departure of a beloved brother, a very early work, showed a gusto for modulation unlike any contemporary work this composition has been compared to,[111] but the full expansion came with the Well-Tempered Clavier, using all keys, which Bach apparently had been developing since around 1720, the Klavierbüchlein für Wilhelm Friedemann Bach being one of its earliest examples.[112]

Ornamentation

The second page of the Klavierbüchlein für Wilhelm Friedemann Bach is an ornament notation and performance guide that Bach wrote for his eldest son, who was nine years old at the time. Bach was generally quite specific on ornamentation in his compositions (where in his time much of the ornamentation was not written out by composers but rather considered a liberty of the performer),[113] and his ornamentation was often quite elaborate. For instance, the "Aria" of the Goldberg Variations has rich ornamentation in nearly every measure. Bach's dealing with ornamentation can also be seen in a keyboard arrangement he made of Marcello's Oboe Concerto: he added explicit ornamentation, which some centuries later is played by oboists when performing the concerto.

Although Bach did not write any operas, he was not averse to the genre or its ornamented vocal style. In church music, Italian composers had imitated the operatic vocal style in genres such as the Neapolitan mass. In Protestant surroundings, there was more reluctance to adopt such a style for liturgical music. For instance, Kuhnau, Bach's predecessor in Leipzig, had notoriously shunned opera and Italian virtuoso vocal music.[114] Bach was less moved. One of the comments after a performance of his St Matthew Passion was that it all sounded much like opera.[115]

Giving soloist roles to continuo instruments

In concerted playing in Bach's time the basso continuo, consisting of instruments such as organ, viola da gamba or harpsichord, usually had the role of accompaniment, providing the harmonic and rhythmic foundation of a piece. From the late 1720s, Bach had the organ play concertante (i.e. as a soloist) with the orchestra in instrumental cantata movements,[116] a decade before Handel published his first organ concertos.[117] Apart from the 5th Brandenburg Concerto and the Triple Concerto, which already had harpsichord soloists in the 1720s, Bach wrote and arranged his harpsichord concertos in the 1730s,[118] and in his sonatas for viola da gamba and harpsichord neither instrument plays a continuo part: they are treated as equal soloists, far beyond the figured bass. In this sense, Bach played a key role in the development of genres such as the keyboard concerto.[119]

Instrumentation

Bach wrote virtuoso music for specific instruments as well as music independent of instrumentation. For instance, the sonatas and partitas for solo violin are considered the pinnacle of what has been written for this instrument, only within reach of accomplished players. The music fits the instrument, pushing it to the full scale of its possibilities and requiring virtuosity of the player but without bravura. Notwithstanding that the music and the instrument seem inseparable, Bach made transcriptions for other instruments of some pieces of this collection. Similarly, for the cello suites, the virtuoso music seems tailored for the instrument, the best of what is offered for it, yet Bach made an arrangement for lute of one of these suites. The same applies to much of his most virtuoso keyboard music. Bach exploited the capabilities of an instrument to the fullest while keeping the core of such music independent of the instrument on which it is performed.

In this sense, it is no surprise that Bach's music is easily and often performed on instruments it was not necessarily written for, that it is transcribed so often, and that his melodies turn up in unexpected places such as jazz music. Apart from this, Bach left a number of compositions without specified instrumentation: the canons BWV 1072–1078 fall in that category, as well as the bulk of the Musical Offering and the Art of Fugue.[120]

Counterpoint

Another characteristic of Bach's style is his extensive use of counterpoint, as opposed to the homophony used in his four-part Chorale settings, for example. Bach's canons, and especially his fugues, are most characteristic of this style, which Bach did not invent but contributed to so fundamentally that he defined it to a large extent. Fugues are as characteristic to Bach's style as, for instance, the Sonata form is characteristic to the composers of the Classical period.[121]

These strictly contrapuntal compositions, and most of Bach's music in general, are characterised by distinct melodic lines for each of the voices, where the chords formed by the notes sounding at a given point follow the rules of four-part harmony. Forkel, Bach's first biographer, gives this description of this feature of Bach's music, which sets it apart from most other music:[122]

If the language of music is merely the utterance of a melodic line, a simple sequence of musical notes, it can justly be accused of poverty. The addition of a Bass puts it upon a harmonic foundation and clarifies it, but defines rather than gives it added richness. A melody so accompanied—even though all the notes are not those of the true Bass—or treated with simple embellishments in the upper parts, or with simple chords, used to be called "homophony." But it is a very different thing when two melodies are so interwoven that they converse together like two persons upon a footing of pleasant equality. In the first case the accompaniment is subordinate, and serves merely to support the first or principal part. In the second case the two parts are not similarly related. New melodic combinations spring from their interweaving, out of which new forms of musical expression emerge. If more parts are interwoven in the same free and independent manner, the apparatus of language is correspondingly enlarged, and becomes practically inexhaustible if, in addition, varieties of form and rhythm are introduced. Hence harmony becomes no longer a mere accompaniment of melody, but rather a potent agency for augmenting the richness and expressiveness of musical conversation. To serve that end a simple accompaniment will not suffice. True harmony is the interweaving of several melodies, which emerge now in the upper, now in the middle, and now in the lower parts. From about the year 1720, when he was thirty-five, until his death in 1750, Bach's harmony consists in this melodic interweaving of independent melodies, so perfect in their union that each part seems to constitute the true melody. Herein Bach excels all the composers in the world. At least, I have found no one to equal him in music known to me. Even in his four-part writing we can, not infrequently, leave out the upper and lower parts and still find the middle parts melodious and agreeable.

Structure and lyrics

Bach devoted more attention than his contemporaries to the structure of compositions. This can be seen in minor adjustments he made when adapting someone else's composition, such as his earliest version of the "Keiser" St Mark Passion, where he enhances scene transitions,[123] and in the architecture of his own compositions such as his Magnificat[110] and Leipzig Passions. In the last years of his life, Bach revised several of his prior compositions. Often the recasting of such previously composed music in an enhanced structure was the most visible change, as in the Mass in B minor. Bach's known preoccupation with structure led (peaking around the 1970s) to various numerological analyses of his compositions, although many such over-interpretations were later rejected, especially when wandering off into symbolism-ridden hermeneutics.[124][125]

The librettos, or lyrics, of his vocal compositions played an important role for Bach. He sought collaboration with various text authors for his cantatas and major vocal compositions, possibly writing or adapting such texts himself to make them fit the structure of the composition he was designing when he could not rely on the talents of other text authors. His collaboration with Picander for the St Matthew Passion libretto is best known, but there was a similar process in achieving a multi-layered structure for his St John Passion libretto a few years earlier.[126]

Compositions

In 1950, Wolfgang Schmieder published a thematic catalogue of Bach's compositions called the Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis (Bach Works Catalogue).[127] Schmieder largely followed the Bach-Gesellschaft-Ausgabe, a comprehensive edition of the composer's works that was produced between 1850 and 1900. The first edition of the catalogue listed 1,080 surviving compositions indisputably composed by Bach.[128]

| BWV Range | Compositions |

|---|---|

| BWV 1–224 | Cantatas |

| BWV 225–231 | Motets |

| BWV 232–243 | Liturgical compositions in Latin |

| BWV 244–249 | Passions and oratorios |

| BWV 250–438 | Four-part chorales |

| BWV 439–524 | Small vocal works |

| BWV 525–771 | Organ compositions |

| BWV 772–994 | Other keyboard works |

| BWV 995–1000 | Lute compositions |

| BWV 1001–1040 | Other chamber music |

| BWV 1041–1071 | Orchestral music |

| BWV 1072–1078 | Canons |

| BWV 1079–1080 | Late contrapuntal works |

BWV 1081–1126 were added to the catalogue in the second half of the 20th century, and BWV 1127 and higher were still later additions.[129][130][131]

Passions and oratorios

Bach composed Passions for Good Friday services and oratorios such as the Christmas Oratorio, which is a set of six cantatas for use in the liturgical season of Christmas.[132][133][134] Shorter oratorios are the Easter Oratorio and the Ascension Oratorio.

St Matthew Passion

With its double choir and orchestra, the St Matthew Passion is one of Bach's most extended works.

St John Passion

The St John Passion was the first Passion Bach composed during his tenure as Thomaskantor in Leipzig.

Cantatas

According to his obituary, Bach would have composed five year-cycles of sacred cantatas, and additional church cantatas for weddings and funerals, for example.[97] Approximately 200 of these sacred works are extant, an estimated two thirds of the total number of church cantatas he composed.[60][135] The Bach Digital website lists 50 known secular cantatas by the composer,[136] about half of which are extant or largely reconstructable.[137]

Church cantatas

Bach's cantatas vary greatly in form and instrumentation, including those for solo singers, single choruses, small instrumental groups, and grand orchestras. Many consist of a large opening chorus followed by one or more recitative-aria pairs for soloists (or duets) and a concluding chorale. The melody of the concluding chorale often appears as a cantus firmus in the opening movement.

Bach's earliest cantatas date from his years in Arnstadt and Mühlhausen. The earliest one with a known date is Christ lag in Todes Banden, BWV 4, for Easter 1707, which is one of his chorale cantatas.[138] Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit, BWV 106, also known as Actus Tragicus, is a funeral cantata from the Mühlhausen period.[139] Around 20 church cantatas are extant from his later years in Weimar, for instance, Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis, BWV 21.[140]

After taking up his office as Thomaskantor in late May 1723, Bach performed a cantata each Sunday and feast day, corresponding to the lectionary readings of the week.[17] His first cantata cycle ran from the first Sunday after Trinity of 1723 to Trinity Sunday the next year. For instance, the Visitation cantata Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben, BWV 147, containing the chorale that is known in English as "Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring", belongs to this first cycle. The cantata cycle of his second year in Leipzig is called the chorale cantata cycle as it consists mainly of works in the chorale cantata format. His third cantata cycle was developed over a period of several years, followed by the Picander cycle of 1728–29.

Later church cantatas include the chorale cantatas Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott, BWV 80 (final version)[141] and Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, BWV 140.[142] Only the first three Leipzig cycles are more or less completely extant. Apart from his own work, Bach also performed cantatas by Telemann and by his distant relative Johann Ludwig Bach.[17]

Secular cantatas

Bach also wrote secular cantatas, for instance for members of the royal Polish and prince-electoral Saxonian families (e.g. Trauer-Ode),[143] or other public or private occasions (e.g. Hunting Cantata).[144] The text of these cantatas was occasionally in dialect (e.g. Peasant Cantata)[145] or Italian (e.g. Amore traditore).[146] Many of the secular cantatas were lost, but for some of them the text and occasion are known, for instance when Picander later published their librettos (e.g. BWV Anh. 11–12).[147] Some of the secular cantatas had a plot involving mythological figures of Greek antiquity (e.g. Der Streit zwischen Phoebus und Pan),[148] and others were almost miniature buffo operas (e.g. Coffee Cantata).[149]

A cappella music

Bach's a cappella music includes motets and chorale harmonisations.

Motets

Bach's motets (BWV 225–231) are pieces on sacred themes for choir and continuo, with instruments playing colla parte. Several of them were composed for funerals.[150] The six motets definitely composed by Bach are Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied, Der Geist hilft unser Schwachheit auf, Jesu, meine Freude, Fürchte dich nicht, Komm, Jesu, komm, and Lobet den Herrn, alle Heiden. The motet Sei Lob und Preis mit Ehren (BWV 231) is part of the composite motet Jauchzet dem Herrn, alle Welt (BWV Anh. 160), other parts of which may be based on work by Telemann.[151]

Chorale harmonisations

Bach wrote hundreds of four-part harmonisations of Lutheran chorales.

Church music in Latin

Bach's church music in Latin includes the Magnificat, four Kyrie–Gloria Masses, and the Mass in B minor.

Magnificat

The first version of Bach's Magnificat dates from 1723, but the work is best known in its D major version of 1733.

Mass in B minor

In 1733 Bach composed a Kyrie–Gloria Mass for the Dresden court. Near the end of his life, around 1748–1749, he expanded this composition into the large-scale Mass in B minor. The work was never performed in full during Bach's lifetime.[152][153]

Keyboard music

Bach wrote for organ and for stringed keyboard instruments such as harpsichord, clavichord and lute-harpsichord.

Organ works

Bach was best known during his lifetime as an organist, organ consultant, and composer of organ works in both the traditional German free genres (such as preludes, fantasias, and toccatas) and stricter forms (such as chorale preludes and fugues).[17] At a young age, he established a reputation for creativity and ability to integrate foreign styles into his organ works. A decidedly North German influence was exerted by Georg Böhm, with whom Bach came into contact in Lüneburg, and Dieterich Buxtehude, whom the young organist visited in Lübeck in 1704 on an extended leave of absence from his job in Arnstadt. Around this time, Bach copied the works of numerous French and Italian composers to gain insights into their compositional languages, and later arranged violin concertos by Vivaldi and others for organ and harpsichord. During his most productive period (1708–1714) he composed about a dozen pairs of preludes and fugues, five toccatas and fugues, and the Little Organ Book, an unfinished collection of 46 short chorale preludes that demonstrate compositional techniques in the setting of chorale tunes. After leaving Weimar, Bach wrote less for organ, although some of his best-known works (the six Organ Sonatas, the German Organ Mass in Clavier-Übung III from 1739, and the Great Eighteen Chorale Preludes, revised late in his life) were composed after leaving Weimar. Bach was extensively engaged later in his life in consulting on organ projects, testing new organs and dedicating organs in afternoon recitals.[154][155] The Canonic Variations on "Vom Himmel hoch da komm' ich her" and the Schübler Chorales are organ works Bach published in the last years of his life.

Harpsichord and other stringed keyboard instruments

Bach wrote many works for harpsichord, some of which may also have been played on the clavichord or lute-harpsichord. Some of his larger works, such as Clavier-Übung II and IV, are intended for a harpsichord with two manuals: performing them on a keyboard instrument with a single manual (like a piano) may present technical difficulties for the crossing of hands.

- The Well-Tempered Clavier, Books 1 and 2 (BWV 846–893). Each book consists of a prelude and fugue in each of the 24 major and minor keys, in chromatic order from C major to B minor (thus, the whole collection is often referred to as "the 48"). "Well-tempered" in the title refers to the temperament (system of tuning); many temperaments before Bach's time were not flexible enough to allow compositions to utilise more than just a few keys.[156][157]

- The Inventions and Sinfonias (BWV 772–801). These short two- and three-part contrapuntal works are arranged in the same chromatic order as The Well-Tempered Clavier, omitting some of the rarer keys. These pieces were intended by Bach for instructional purposes.[158]

- Three collections of dance suites: the English Suites (BWV 806–811), French Suites (BWV 812–817), and Partitas for keyboard (Clavier-Übung I, BWV 825–830). Each collection contains six suites built on the standard model (allemande–courante–sarabande–(optional movement)–gigue). The English Suites closely follow the traditional model, adding a prelude before the allemande and including a single movement between the sarabande and gigue.[159] The French Suites omit preludes but have multiple movements between the sarabande and gigue.[160] The partitas expand the model further with elaborate introductory movements and miscellaneous movements between the basic elements of the model.[161]

- The Goldberg Variations (BWV 988), an aria with 30 variations. The collection has a complex and unconventional structure: the variations build on the bass line of the aria rather than its melody, and musical canons are interpolated according to a grand plan. There are 9 canons within the 30 variations; every third variation is a canon.[162] These variations move in order from canon at unison to canon at the ninth. The first eight are in pairs (unison and octave, second and seventh, third and sixth, fourth and fifth). The ninth canon stands on its own due to compositional dissimilarities. The final variation, instead of being the expected canon at the tenth, is a quodlibet.

- Miscellaneous pieces such as the Overture in the French Style (French Overture, BWV 831) and the Italian Concerto (BWV 971) (published together as Clavier-Übung II), and the Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue (BWV 903).

Among Bach's lesser known keyboard works are seven toccatas (BWV 910–916), four duets (BWV 802–805), sonatas for keyboard (BWV 963–967), the Six Little Preludes (BWV 933–938), and the Aria variata alla maniera italiana (BWV 989).

Orchestral and chamber music

Bach wrote for single instruments, duets, and small ensembles. Many of his solo works, such as the six sonatas and partitas for violin (BWV 1001–1006) and the six cello suites (BWV 1007–1012), are widely considered to be among the most profound in the repertoire.[163] He wrote sonatas for a solo instrument such as the viola de gamba accompanied by harpsichord or continuo, as well as trio sonatas (two instruments and continuo).

The Musical Offering and The Art of Fugue are late contrapuntal works containing pieces for unspecified instruments or combinations of instruments.

Violin concertos

Surviving works in the concerto form include two violin concertos (BWV 1041 in A minor and BWV 1042 in E major) and a concerto for two violins in D minor, BWV 1043, often referred to as Bach's "double concerto".

Brandenburg Concertos

Bach's best-known orchestral works are the Brandenburg Concertos, so named because he submitted them in the hope of gaining employment from Margrave Christian Ludwig of Brandenburg-Schwedt in 1721; his application was unsuccessful.[17] These works are examples of the concerto grosso genre.

Keyboard concertos

Bach composed and transcribed concertos for one to four harpsichords. Many of the harpsichord concertos were not original works but arrangements of his concertos for other instruments, now lost.[164] A number of violin, oboe, and flute concertos have been reconstructed from these.

Orchestral suites

In addition to concertos, Bach wrote four orchestral suites, each suite being a series of stylised dances for orchestra, preceded by a French overture.[165]

Copies, arrangements and works with an uncertain attribution

In his early youth, Bach copied pieces by other composers to learn from them.[166] Later, he copied and arranged music for performance or as study material for his pupils. Some of these pieces, like "Bist du bei mir" (copied not by Bach but by Anna Magdalena), became famous before being dissociated with Bach. Bach copied and arranged Italian masters such as Vivaldi (e.g. BWV 1065), Pergolesi (BWV 1083) and Palestrina (Missa Sine nomine), French masters such as François Couperin (BWV Anh. 183), and, closer to home, various German masters including Telemann (e.g. BWV 824=TWV 32:14) and Handel (arias from Brockes Passion), and music from members of his own family. He also often copied and arranged his own music (e.g. movements from cantatas for his short masses BWV 233–236), as his music was likewise copied and arranged by others. Some of these arrangements, like the late 19th-century "Air on the G String", helped in popularising Bach's music.

Sometimes "who copied whom" is not clear. For instance, Forkel mentions a Mass for double chorus among the works composed by Bach. The work was published and performed in the early 19th century, and although a score partially in Bach's handwriting exists, the work was later considered spurious.[167] In 1950, the design of the Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis was to keep such works out of the main catalogue: if there was a strong association with Bach they could be listed in its appendix (German: Anhang, abbreviated as Anh.). Thus, for instance, the aforementioned Mass for double chorus became BWV Anh. 167. But this was far from the end of the attribution issues. For instance, Schlage doch, gewünschte Stunde, BWV 53, was later attributed to Melchior Hoffmann. For other works, Bach's authorship was put in doubt without a generally accepted answer to the question of whether or not he composed it: the best known organ composition in the BWV catalogue, the Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 565, was indicated as one of these uncertain works in the late 20th century.[168]

Reception

_-_Holzstich.jpg)

Throughout the 18th century, the appreciation of Bach's music was mostly limited to distinguished connoisseurs. The 19th century started with publication of the first biography of the composer and ended with the completion of the publication of all of Bach's known works by the Bach Gesellschaft. A Bach Revival had started from Mendelssohn's performance of the St Matthew Passion in 1829. Soon after that performance, Bach started to become regarded as one of the greatest composers of all times, if not the greatest, a reputation he has retained ever since. A new extensive Bach biography was published in the second half of the 19th century.

In the 20th century, Bach's music was widely performed and recorded, while the Neue Bachgesellschaft, among others, published research on the composer. Modern adaptations of Bach's music contributed greatly to his popularisation in the second half of the 20th century. Among these were the Swingle Singers' versions of Bach pieces (for instance, the Air from Orchestral Suite No. 3, or the Wachet auf... chorale prelude) and Wendy Carlos' 1968 Switched-On Bach, which used the Moog electronic synthesiser.

By the end of the 20th century, more classical performers were gradually moving away from the performance style and instrumentation that were established in the romantic era: they started to perform Bach's music on period instruments of the baroque era, studied and practised playing techniques and tempi as established in his time, and reduced the size of instrumental ensembles and choirs to what he would have employed. The BACH motif, used by the composer in his own compositions, was used in dozens of tributes to the composer from the 19th century to the 21st. In the 21st century, the complete extant output of the composer became available on-line, with several websites exclusively dedicated to him.

18th century

In his own time, Bach's reputation equalled that of Telemann, Graun and Handel.[169] During his life, Bach received public recognition, such as the title of court composer by Augustus III of Poland and the appreciation he was shown by Frederick the Great and Hermann Karl von Keyserling. Such highly placed appreciation contrasted with the humiliations he had to cope with, for instance in his hometown of Leipzig.[170] Also in the contemporary press, Bach had his detractors, such as Johann Adolf Scheibe, suggesting he write less complex music, and his supporters, such as Johann Mattheson and Lorenz Christoph Mizler.[171][172][173]

After his death, Bach's reputation as a composer at first declined: his work was regarded as old-fashioned compared to the emerging galant style.[174] Initially, he was remembered more as a virtuoso player of the organ and as a teacher. The bulk of the music that had been printed during the composer's lifetime, at least the part that was remembered, was for the organ and the harpsichord. Thus, his reputation as a composer was initially mostly limited to his keyboard music, and that even fairly limited to its value in music education.

Bach's surviving family members, who inherited a large part of his manuscripts, were not all equally concerned with preserving them, leading to considerable losses.[175] Carl Philipp Emanuel, his second eldest son, was most active in safeguarding his father's legacy: he co-authored his father's obituary, contributed to the publication of his four-part chorales,[176] staged some of his works, and the bulk of previously unpublished works of his father were preserved with his help.[177] Wilhelm Friedemann, the eldest son, performed several of his father's cantatas in Halle but after becoming unemployed sold part of the large collection of his father's works he owned.[178][179][180] Several students of the old master, such as his son-in-law Johann Christoph Altnickol, Johann Friedrich Agricola, Johann Kirnberger, and Johann Ludwig Krebs, contributed to the dissemination of his legacy. The early devotees were not all musicians; for example, in Berlin, Daniel Itzig, a high official of Frederick the Great's court, venerated Bach.[181] His eldest daughters took lessons from Kirnberger and their sister Sara from Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, who was in Berlin from 1774 to 1784.[181][182] Sara Itzig Levy became an avid collector of works by Johann Sebastian Bach and his sons and was a "patron" of CPE Bach.[182]

While in Leipzig, performances of Bach's church music were limited to some of his motets, and under cantor Doles some of his Passions.[183] A new generation of Bach aficionados emerged: they studiously collected and copied his music, including some of his large-scale works such as the Mass in B minor and performed it privately. One such connoisseur was Gottfried van Swieten, a high-ranking Austrian official who was instrumental in passing Bach's legacy on to the composers of the Viennese school. Haydn owned manuscript copies of the Well-Tempered Clavier and the Mass in B minor and was influenced by Bach's music. Mozart owned a copy of one of Bach's motets,[184] transcribed some of his instrumental works (K. 404a, 405),[185][186] and wrote contrapuntal music influenced by his style.[187][188] Beethoven played the entire Well-Tempered Clavier by the time he was 11 and described Bach as Urvater der Harmonie (progenitor of harmony).[189][190][191][192][193]

19th century

In 1802, Johann Nikolaus Forkel published Ueber Johann Sebastian Bachs Leben, Kunst und Kunstwerke, the first biography of the composer, which contributed to his becoming known to a wider public.[194] In 1805, Abraham Mendelssohn, who had married one of Itzig's granddaughters, bought a substantial collection of Bach manuscripts that had come down from C. P. E. Bach, and donated it to the Berlin Sing-Akademie.[181] The Sing-Akademie occasionally performed Bach's works in public concerts, for instance his first keyboard concerto, with Sara Itzig Levy at the piano.[181]

The first decades of the 19th century saw an increasing number of first publications of Bach's music: Breitkopf started publishing chorale preludes,[195] Hoffmeister harpsichord music,[196] and the Well-Tempered Clavier was printed concurrently by Simrock (Germany), Nägeli (Switzerland) and Hoffmeister (Germany and Austria) in 1801.[197] Vocal music was also published: motets in 1802 and 1803, followed by the E♭ major version of the Magnificat, the Kyrie-Gloria Mass in A major, and the cantata Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott (BWV 80).[198] In 1818, Hans Georg Nägeli called the Mass in B minor the greatest composition ever.[189] Bach's influence was felt in the next generation of early Romantic composers.[190] When Felix Mendelssohn, Abraham's son, aged 13, produced his first Magnificat setting in 1822, it is clear that he was inspired by the then unpublished D major version of Bach's Magnificat.[199]

Felix Mendelssohn significantly contributed to the renewed interest in Bach's work with his 1829 Berlin performance of the St Matthew Passion, which was instrumental in setting off what has been called the Bach Revival. The St John Passion saw its 19th-century premiere in 1833, and the first performance of the Mass in B minor followed in 1844. Besides these and other public performances and an increased coverage on the composer and his compositions in printed media, the 1830s and 1840s also saw the first publication of more vocal works by Bach: six cantatas, the St Matthew Passion, and the Mass in B minor. A series of organ compositions saw their first publication in 1833.[200] Chopin started composing his 24 Preludes, Op. 28, inspired by the Well-Tempered Clavier, in 1835, and Schumann published his Sechs Fugen über den Namen B-A-C-H in 1845. Bach's music was transcribed and arranged to suit contemporary tastes and performance practice by composers such as Carl Friedrich Zelter, Robert Franz, and Franz Liszt, or combined with new music such as the melody line of Charles Gounod's Ave Maria.[189][201] Brahms, Bruckner, and Wagner were among the composers who promoted Bach's music or wrote glowingly about it.

In 1850, the Bach-Gesellschaft (Bach Society) was founded to promote Bach's music. In the second half of the 19th century, the Society published a comprehensive edition of the composer's works. Also in the second half of the 19th century, Philipp Spitta published Johann Sebastian Bach, the standard work on Bach's life and music.[202] By that time, Bach was known as the first of the three Bs in music. Throughout the 19th century, 200 books were published on Bach. By the end of the century, local Bach societies were established in several cities, and his music had been performed in all major musical centres.[189]

In Germany all throughout the century, Bach was coupled to nationalist feelings, and the composer was inscribed in a religious revival. In England, Bach was coupled to an existing revival of religious and baroque music. By the end of the century, Bach was firmly established as one of the greatest composers, recognised for both his instrumental and his vocal music.[189]

20th century

During the 20th century, the process of recognising the musical as well as the pedagogic value of some of the works continued, as in the promotion of the cello suites by Pablo Casals, the first major performer to record these suites.[203] Leading performers of classical music such as Willem Mengelberg, Edwin Fischer, Georges Enescu, Leopold Stokowski, Herbert von Karajan, Arthur Grumiaux, Helmut Walcha, Wanda Landowska, Karl Richter, I Musici, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Glenn Gould recorded his music.[204]

A significant development in the later part of the 20th century was the momentum gained by the historically informed performance practice, with forerunners such as Nikolaus Harnoncourt acquiring prominence by their performances of Bach's music. His keyboard music was again performed more on the instruments Bach was familiar with, rather than on modern pianos and 19th-century romantic organs. Ensembles playing and singing Bach's music not only kept to the instruments and the performance style of his day but were also reduced to the size of the groups Bach used for his performances.[205] But that was far from the only way Bach's music came to the forefront in the 20th century: his music was heard in versions ranging from Ferruccio Busoni's late romantic piano transcriptions to jazzy interpretations such as those by The Swingle Singers, orchestrations like the one opening Walt Disney's Fantasia movie, and synthesiser performances such as Wendy Carlos' Switched-On Bach recordings.

Bach's music has influenced other genres. For instance, jazz musicians have adopted Bach's music, with Jacques Loussier, Ian Anderson, Uri Caine, and the Modern Jazz Quartet among those creating jazz versions of his works.[206] Several 20th-century composers referred to Bach or his music, for example Eugène Ysaÿe in Six Sonatas for solo violin, Dmitri Shostakovich in 24 Preludes and Fugues and Heitor Villa-Lobos in Bachianas Brasileiras. All kinds of publications involved Bach: not only were there the Bach Jahrbuch publications of the Neue Bachgesellschaft, various other biographies and studies by among others Albert Schweitzer, Charles Sanford Terry, Alfred Dürr, Christoph Wolff. Peter Williams, John Butt,[207] and the 1950 first edition of the Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis; but also books such as Gödel, Escher, Bach put the composer's art in a wider perspective. Bach's music was extensively listened to, performed, broadcast, arranged, adapted, and commented upon in the 1990s.[208] Around 2000, the 250th anniversary of Bach's death, three record companies issued box sets with complete recordings of Bach's music.[209][210][211]

Bach's music features three times—more than that of any other composer—on the Voyager Golden Record, a gramophone record containing a broad sample of the images, common sounds, languages, and music of Earth, sent into outer space with the two Voyager probes.[212] Tributes to Bach in the 20th century include statues erected in his honour and a variety of things such as streets and space objects being named after him.[213][214] Also, a multitude of musical ensembles such as the Bach Aria Group, Deutsche Bachsolisten, Bachchor Stuttgart, and Bach Collegium Japan adopted the composer's name. Bach festivals were held on several continents, and competitions and prizes such as the International Johann Sebastian Bach Competition and the Royal Academy of Music Bach Prize were named after the composer. While by the end of the 19th century Bach had been inscribed in nationalism and religious revival, the late 20th century saw Bach as the subject of a secularised art-as-religion (Kunstreligion).[189][208]

21st century

In the 21st century, Bach's compositions have become available online, for instance at the International Music Score Library Project.[215] High-resolution facsimiles of Bach's autographs became available at the Bach Digital website.[216] 21st-century biographers include Christoph Wolff, Peter Williams and John Eliot Gardiner.[217]

In 2019, Bach was named the greatest composer of all time in a poll conducted among 174 living composers.[218]

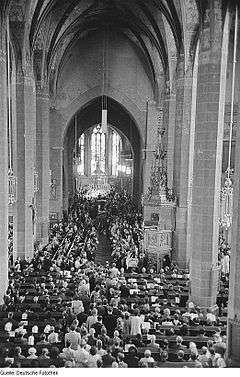

Burial site

Bach was originally buried at Old St. John's Cemetery in Leipzig. His grave went unmarked for nearly 150 years, but in 1894 his remains were located and moved to a vault in St. John's Church. This building was destroyed by Allied bombing during World War II, so in 1950 Bach's remains were taken to their present grave in St. Thomas Church.[17] Later research has called into question whether the remains in the grave are actually those of Bach.[219]

Recognition in Protestant churches

The liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church remembers Bach annually with a feast day on 28 July, together with George Frideric Handel and Henry Purcell; on the same day, the Calendar of Saints of the Lutheran Church remembers Bach and Handel with Heinrich Schütz.

References

Footnotes

- German: [ˈjoːhan zeˈbasti̯an ˈbax] (

Citations

- "Bach, Johann Sebastian Archived 11 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine" entry at www

.oxforddictionaries . Retrieved 3 May 2016..com - "Bach" entry at Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- Blanning, T. C. W. (2008). The Triumph of Music: The Rise of Composers, Musicians and Their Art. p. 272. ISBN 9780674031043.

And of course the greatest master of harmony and counterpoint of all time was Johann Sebastian Bach, 'the Homer of music'.

- "The 50 Greatest Composers of All Time". www.classical-music.com.

- Wolff (2000), pp. 19, 46

- "Bach Mass in B Minor BWV 232". The Baroque Music Site. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- Miles (1962), pp. 86–87

- Johann Günther Rörer (editor). Neues vollständiges Eisenachisches Gesangbuch: Worinnen in ziemlich bequeemer und füglicher Ordnung vermittels fünffacher Abteilung so wol die alte als neue doch mehrenteils bekante geistliche Kirchenlieder und Psalmen D. Martin Luthers und anderer Gottseeligen Männer befindlich. Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Eisenach: Rörer, 1673.

- Geck 2003, p. 5 Archived 28 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Jones (2007), p. 3

- "Lesson Plans". Bach to School. The Bach Choir of Bethlehem. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- Boyd (2000), p. 6

- Johann Sebastian Bach drafted a genealogy around 1735, titled "Origin of the musical Bach family", printed in translation in David, Mendel, and Wolff (1998), p. 283

- Boyd (2000), pp. 7–8

- David, Mendel & Wolff (1998), p. 299

- Wolff (2000), p. 45

- "Johann Sebastian Bach: a detailed informative biography". The Baroque Music Site. Archived from the original on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- Wolff (2000), pp. 41–43

- Eidam 2001, Ch. I

- Stauffer, George B. (20 February 2014). "Why Bach Moves Us". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- Geiringer (1966), p. 13

- Towe, Teri Noel. "The Portrait in Erfurt Alleged to Depict Bach, the Weimar Concertmeister". The Face of Bach. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- Rich (1995), p. 27

- Boyd (2000), pp. 15–16

- Chiapusso (1968), p. 62

- "Bach's biography: professional organist (1703 - 1708)". Classic FM. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- Wolff (2000), pp. 83ff Archived 28 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Snyder, Kerala J. (2007). Dieterich Buxtehude: Organist in Lübeck (2nd ed.). pp. 104–106. ISBN 9781580462532. Archived from the original on 28 September 2015.

- Wolff (2000), pp. 102–104 Archived 22 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine)

- Williams (2003), pp. 38–39 Archived 22 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Bach Digital Work 00005 at www

.bach-digital .de - "History of the Bach House". Bach House Weimar. Archived from the original on 26 November 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- Forkel/Terry 1920, Table VII, p. 309

- Thornburgh, Elaine. "Baroque Music – Part One". Music in Our World. San Diego State University. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- Chiapusso (1968), p. 168

- Schweitzer (1935), p. 331

- Koster, Jan. "Weimar (II) 1708–1717". J. S. Bach Archive and Bibliography. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- Sadie, Julie Anne, ed. (1998). Companion to Baroque Music. p. 205. ISBN 9780520214149. Archived from the original on 14 May 2015.

- Wolff (2000), pp. 147, 156

- Wolff (1991), p. 30

- Gardiner, John Eliot (2010). "Cantatas for Christmas Day: Herderkirche, Weimar" (PDF). pp. 1–2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- Wolff, Christoph (1996). "From konzertmeister to thomaskantor: Bach's cantata production 1713–1723" (PDF). pp. 15–16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- David, Mendel & Wolff (1998), p. 80

- Miles (1962), p. 57

- Boyd (2000), p. 74

- Van Til (2007), pp. 69, 372

- Spaeth (1937), p. 37

- Spitta (1899a), p. 11

- Geiringer (1966), p. 50

- Wolff (1983), pp. 98, 111

- David, Mendel & Wolff (1998), p. 297

- Spitta (1899a), pp. 192–193

- Wolff 2013, p. 253

- Wolff 2013, p. 345

- Spitta (1899a), p. 265

- Spitta (1899a), p. 184

- British Library. On-line gallery.Bach biography. Archived 29 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Wolff 2013, p. 348

- Wolff 2013, p. 349

- Wolff (1997), p. 5

- "Motets BWV 225–231". Bach Cantatas Website. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- "Works of Other Composers performed by J.S. Bach". Bach Cantatas Website. Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- Boyd (2000), pp. 112–113

- Spitta (1899a), pp. 288–290

- Spitta (1899a), pp. 281, 287

- Wolff (2000), p. 341

- US-PRu M 3.1. B2 C5. 1739q Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- GB-Lbl Add. MS. 35021 Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- D-B Mus. ms. 16714 Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- D-Cv A.V,1109,(1), 1a Archived 18 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine and 1b Archived 18 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- D-B Mus. ms. Bach P 195 Archived 18 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- D-B Mus. ms. 1160 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- D-WFe 191 Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website (RISM No. 250000899)

- D-Bsa SA 301, Fascicle 1 Archived 18 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine and Fascicle 2 Archived 18 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- Neuaufgefundenes Bach-Autograph in Weißenfels Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine at lisa

.gerda-henkel-stiftung .de - F-Pn Ms. 17669 Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- D-B N. Mus. ms. 468 Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine and Privatbesitz C. Thiele, BWV deest (NBA Serie II:5) Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- D-B N. Mus. ms. 307 Archived 8 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- D-B Mus. ms. Bach P 271, Fascicle 2 Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- D-B Mus. ms. 30199, Fascicle 14 Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine and D-B Mus. ms. 17155/16 Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- D-B Mus. ms. 7918 Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine at Bach Digital website

- Musikalische Bibliothek, III.2 [1746], 353 Archived 16 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Felbick 2012, 284. In 1746, Mizler announced the membership of three famous members, Musikalische Bibliothek, III.2 [1746], 357 Archived 16 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- Musikalische Bibliothek, IV.1 [1754], 108 and Tab. IV, fig. 16 (Source online); letter of Mizler to Spieß, 29 June 1748, in: Hans Rudolf Jung und Hans-Eberhard Dentler: Briefe von Lorenz Mizler und Zeitgenossen an Meinrad Spieß, in: Studi musicali 2003, Nr. 32, 115.

- US-PRscheide BWV 645-650 Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine (original print of the Schübler Chorales with Bach's handwritten corrections and additions from before August 1748 – description at Bach Digital website)

- Breig, Werner (2010). "Introduction Archived 22 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine" (pp. 14, 17–18) in Vol. 6: Clavierübung III, Schübler-Chorales, Canonische Veränderungen Archived 11 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine of Johann Sebastian Bach: Complete Organ Works. Archived 5 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Breitkopf.

- Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel & Agricola, Johann Friedrich (1754). "Nekrolog". Musikalische Bibliothek (in German). Leipzig: Mizlerischer Bücherverlag. IV.1: 173.

- Hans Gunter Hoke: "Neue Studien zur Kunst der Fuge BWV 1080", in: Beiträge zur Musikwissenschaft 17 (1975), 95–115; Hans-Eberhard Dentler: "Johann Sebastian Bachs Kunst der Fuge – Ein pythagoreisches Werk und seine Verwirklichung", Mainz 2004; Hans-Eberhard Dentler: "Johann Sebastian Bachs Musicalisches Opfer – Musik als Abbild der Sphärenharmonie", Mainz 2008.

- Chiapusso (1968), p. 277

- Rathey, Markus (18 April 2003). Johann Sebastian Bach's Mass in B Minor: The Greatest Artwork of All Times and All People (PDF). The Tangeman Lecture. New Haven. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 July 2014.

- Wolff (2000), p. 442, from David, Mendel & Wolff (1998)

- Zegers, Richard H.C. (2005). "The Eyes of Johann Sebastian Bach". Archives of Ophthalmology. 123 (10): 1427–1430. doi:10.1001/archopht.123.10.1427. PMID 16219736.

- Hanford, Jan. "J.S. Bach: Timeline of His Life". J.S. Bach Home Page. Archived from the original on 26 February 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- David, Mendel & Wolff (1998), p. 188

- Spitta (1899b), p. 274

- David, Mendel & Wolff (1998), pp. 191–197

- "Did Bach really leave Art of Fugue unfinished?". The Art of Fugue. American Public Media. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel & Agricola, Johann Friedrich (1754). "Nekrolog". Musikalische Bibliothek (in German). Leipzig: Mizlerischer Bücherverlag. IV.1: 158–173. Printed in translation in David, Mendel & Wolff (1998), p. 299.

- Wolff (2000), p. 166

- https://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/musicmanu/bach/

- Herl (2004), p. 123

- Fuller Maitland, J.A., ed. (1911). "Johann Sebastian Bach". Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians. 1. New York: Macmillan Publishers. p. 154.

- Leaver (2007), pp. 280, 289–291

- Huizenga, Tom. "A Visitor's Guide to the St. Matthew Passion". NPR Music. National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- Traupman-Carr, Carol. "The Well Tempered Clavier BWV 846–869". Bach 101. Bach Choir of Bethlehem. Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- Spitta III (1899b), Appendix XII p. 315

- Clemens Romijn. Liner notes for Tilge, Höchster, meine Sünden, BWV 1083 (after Pergolesi's Stabat Mater). Brilliant Classics, 2000. (2014 reissue: J.S. Bach Complete Edition. "Liner notes" Archived 22 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine p. 54)

- Jopi Harri. St. Petersburg Court Chant and the Tradition of Eastern Slavic Church Singing. Archived 20 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine Finland: University of Turku (2011), p. 24

- Eidam 2001, Ch. IV

- Eidam 2001, Ch. IX