Luigi Galvani

Luigi Galvani (/ɡælˈvɑːni/, also US: /ɡɑːl-/,[1][2][3][4] Italian: [luˈiːdʒi ɡalˈvaːni]; Latin: Aloysius Galvanus; 9 September 1737 – 4 December 1798) was an Italian physician, physicist, biologist and philosopher, who discovered animal electricity. He is recognized as the pioneer of bioelectromagnetics. In 1780, he discovered that the muscles of dead frogs' legs twitched when struck by an electrical spark.[5]:67–71 This was one of the first forays into the study of bioelectricity, a field that studies the electrical patterns and signals from tissues such as the nerves and muscles.

Luigi Galvani | |

|---|---|

Luigi Galvani; physician famous for pioneering bioelectricity | |

| Born | 9 September 1737 |

| Died | 4 December 1798 (aged 61) Bologna, Papal States |

| Known for | Bioelectricity (animal electricity) |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | University of Bologna |

Early life

Luigi Galvani was born to Domenico and Barbara Caterina Foschi, in Bologna, then part of the Papal States.[6] Domenico was a goldsmith,[6] and Barbara was his fourth wife. His family was not aristocratic, but they could afford to send at least one of their sons to study at a university. At first, Galvani wished to enter the church, so he joined a religious institution, Oratorio dei Padri Filippini, at 15 years old. He planned to take religious vows, but his parents persuaded him not to do so. Around 1755, Galvani entered the Faculty of the Arts of the University of Bologna. Galvani attended the medicine course, which lasted four years, and was characterized by its "bookish" teaching. Texts that dominated this course were by Hippocrates, Galen, and Avicenna.

Another discipline Galvani learned alongside medicine was surgery. He learned the theory and practice. This part of his biography is typically overlooked, but it helped with his experiments with animals and helped familiarize Galvani with the manipulation of a living body.

In 1759, Galvani graduated with degrees in medicine and philosophy. He applied for a position as a lecturer at the university. Part of this process required him to defend his thesis on 21 June 1761. In the following year, 1762, he became a permanent anatomist of the university and was appointed honorary lecturer of surgery. That same year he married Lucia Galeazzi, daughter of one of his professors, Gusmano Galeazzi. Galvani moved into the Galeazzi house and helped with his father-in-law's research. When Galeazzi died in 1775, Galvani was appointed professor and lecturer in Galeazzi's place.

Galvani moved from the position of lecturer of surgery to theoretical anatomy and obtained an appointment at the Academy of Sciences in 1776. His new appointment consisted of the practical teaching of anatomy, which was conducted by human dissection and the use of the famous anatomical waxes.

As a "Benedectine member" of the Academy of Sciences, Galvani had specific responsibilities. His main responsibility was to present at least one research paper every year at the Academy, which Galvani did until his death. There was a periodical publication that collected a selection of the memoirs presented at the institution and was sent around to main scientific academies and institutions around the world. However, since publication then was so slow, sometimes there were debates on the priority of the topics used. One of these debates occurred with Antonio Scarpa. This debate caused Galvani to give up the field of research on which he had presented for four years in a row: the hearing of birds, quadrupeds, and humans. Galvani had announced all of the findings in his talks but had yet to publish them. It is suspected that Scarpa attended Galvani's public dissertation and claimed some of Galvani's discoveries without crediting him.

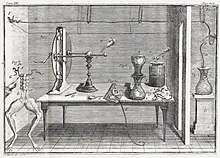

Galvani then began taking an interest in the field of "medical electricity". This field emerged in the middle of the 18th century, following the electrical researches and the discovery of the effects of electricity on the human body.[7]

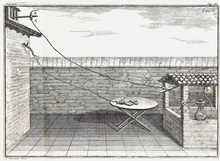

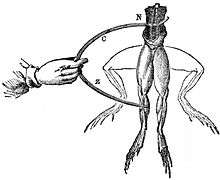

The beginning of Galvani's experiments with bioelectricity has a popular legend which says that the Galvani was slowly skinning a frog at a table where he and his wife had been conducting experiments with static electricity by rubbing frog skin. Galvani's assistant touched an exposed sciatic nerve of the frog with a metal scalpel that had picked up a charge. At that moment, they saw sparks and the dead frog's leg kicked as if in life. The observation made the Galvanis the first investigators to appreciate the relationship between electricity and animation—or life. This finding provided the basis for the new understanding that the impetus behind muscle movement was electrical energy carried by a liquid (ions), and not air or fluid as in earlier balloonist theories.

Galvani coined the term animal electricity to describe the force that activated the muscles of his specimens. Along with contemporaries, he regarded their activation as being generated by an electrical fluid that is carried to the muscles by the nerves. The phenomenon was dubbed galvanism, after Galvani and his wife, on the suggestion of his peer and sometime intellectual adversary Alessandro Volta. The Galvanis are properly credited with the discovery of bioelectricity. Today, the study of galvanic effects in biology is called electrophysiology, the term galvanism being used only in historical contexts.

Galvani vs. Volta

Volta, a professor of experimental physics in the University of Pavia, was among the first scientists who repeated and checked Galvani’s experiments. At first, he embraced animal electricity. However, he started to doubt that the conductions were caused by specific electricity intrinsic to the animal's legs or other body parts. Volta believed that the contractions depended on the metal cable Galvani used to connect the nerves and muscles in his experiments.[7]

Volta's investigations led shortly to the invention of an early battery. Galvani believed that the animal electricity came from the muscle in its pelvis. Volta, in opposition, reasoned that the animal electricity was rather a metallic electricity caused by the interactions between the two metals involved in the experiment.

Every cell has a cell potential; biological electricity has the same chemical underpinnings as the current between electrochemical cells, and thus can be duplicated outside the body. Volta's intuition was correct. Volta, essentially, objected to Galvani’s conclusions about "animal electric fluid", but the two scientists disagreed respectfully and Volta coined the term "Galvanism" for a direct current of electricity produced by chemical action.[9] Thus, owing to an argument between the two in regard to the source or cause of the electricity, Volta built the first battery in order to specifically disprove his associate's theory. Volta's “pile” became known therefore as a voltaic pile.

After the controversy with Volta, Galvani kept a low profile partly because of his attitude towards the controversy, and partly because his health and spirits had declined, especially after the death of his wife, Lucia, in 1790.

Since Galvani was reluctant to intervene in the controversy with Volta, he trusted his nephew, Giovanni Aldini, to act as the main defender of the theory of animal electricity.[7]

Galvani’s landmarks in Bologna

Galvani’s home in Bologna has been preserved and can be seen in the central.

Galvani’s monument. In the square dedicated to him, facing the palace of the Archiginnasio, the ancient seat of the University of Bologna, a big marble statue has been erected to the scientist while observing one of his famous frog experiments.

Liceo Ginnasio Luigi Galvani. This famous secondary school (Liceo) dating back to 1860 was named after Luigi Galvani.

Religious beliefs are- Galvani, according to William Fox, was “by nature courageous and religious.” [Jean-Louis-Marc Alibert]said of Galvani that he never ended his lessons “without exhorting his hearers and leading them back to the idea of that eternal Providence, which develops, conserves, and circulates life among so many diverse beings.”[10]

Death and legacy

Galvani actively investigated animal electricity until the end of his life. The Cisalpine Republic, a French client state founded in 1797 after the French occupation of Northern Italy, required every university professor to swear loyalty to the new authority. Galvani, who disagreed with the social and political confusion, refused to swear loyalty, along with other colleagues. This led to the new authority depriving him of all his academic and public positions, which took every financial support away. Galvani died peacefully surrounded by his mother and father, in his brother’s house depressed and in poverty, on 4 December 1798.[7]

Galvani's legacy includes:

- Galvani's report of his investigations were mentioned specifically by Mary Shelley as part of the summer reading list leading up to an ad hoc ghost story contest on a rainy day in Switzerland—and the resultant novel Frankenstein—and its reanimated construct. In Frankenstein, Victor studies the principles of galvanism but is not mentioned in reference to the creation of the Monster.

- Galvani's name also survives as a verb in everyday language (galvanize) as well as in more specialized terms: Galvanic cell, Galvani potential, galvanic corrosion, the galvanometer, galvanization, and Galvanic skin response.

- The crater Galvani on the Moon is named after him.

- The Società Chimica Italiana awards a medal to recognize the work of foreign electrochemists.

- R&D bioelectronics company Galvani Bioelectronics is named after him

- There is a statue of Galvani in his native Bologna in the eponyous Piazza Galvani.

- There are streets named after Galvani in Le Havre, France; Antony, Hauts-de-Seine; Bolzano, South Tyrol; and Bucharest, Romania.

Works

- De viribus electricitatis, 1791. The International Centre for the History of Universities and Science (CIS), Università di Bologna

References

- "Galvani". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- "Galvani". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- "Galvani, Luigi" (US) and "Galvani, Luigi". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- "Galvani". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- Whittaker, E. T. (1951), A history of the theories of aether and electricity. Vol 1, Nelson, London

- Heilbron 2003, p. 323.

- Bresadola, Marco (15 July 1998). "Medicine and science in the life of Luigi Galvani". Brain Research Bulletin. 46 (5): 367–380. doi:10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00023-9. PMID 9739000.

- David Ames Wells, The science of common things: a familiar explanation of the first, 323 pages ( page 290)

- Luigi Galvani – IEEE Global History Network.

- "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Luigi Galvani". Retrieved 1 September 2014.

Sources

- Heilbron, John L., ed. (2003). The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199743766.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia article Luigi Galvani. |

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.