Hong Taiji

Hong Taiji (28 November 1592 – 21 September 1643), sometimes written as Huang Taiji and formerly referred to as Abahai in Western literature, was the second khan of the Later Jin (reigned from 1626 to 1636) and the founding emperor of the Qing dynasty (reigned from 1636 to 1643). He was responsible for consolidating the empire that his father Nurhaci had founded and laid the groundwork for the conquest of the Ming dynasty, although he died before this was accomplished. He was also responsible for changing the name of the Jurchen ethnicity to "Manchu" in 1635, and changing the name of his dynasty from "Great Jin" to "Great Qing" in 1636. The Qing dynasty lasted until 1912.

| Hong Taiji | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

| 2nd Khan of Later Jin | |||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 20 October 1626 – 1636 | ||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Nurhaci | ||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Himself as the Emperor of the Qing dynasty | ||||||||||||||||

| 1st Emperor of the Qing dynasty | |||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 1636 – 21 September 1643 | ||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Himself as the Khan of Later Jin | ||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Fulin, Shunzi Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

| Born | Aisin Gioro Hong Taiji (愛新覺羅 皇太極) 28 November 1592 (萬曆二十年 十月 二十五日) Fu Ala, Manchuria | ||||||||||||||||

| Died | 21 September 1643 (aged 50) (崇德八年 八月 九日) | ||||||||||||||||

| Burial | |||||||||||||||||

| Consorts | Lady Niohuru ( died 1612)Lady Ula Nara ( div. 1623) | ||||||||||||||||

| Issue | Hooge, Prince Suwu of the First Rank Yebušu Šose, Prince Chengzeyu of the First Rank Gose Cangšu Shunzhi Emperor Toose Bomubogor Princess Aohan of the First Rank Princess Wenzhuang of the First Rank Princess Jingduan of the First Rank Princess Yongmu of the First Rank Princess Shuhui of the First Rank Princess of the First Rank Princess Shuzhe of the First Rank Princess Yong'an of the First Rank Lady of the Second Rank Princess Duanshun of the First Rank Lady of the Third Rank Princess Kechun of the Second Rank | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| House | Aisin Gioro | ||||||||||||||||

| Father | Nurhaci | ||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Empress Xiao Ci Gao | ||||||||||||||||

| Hong Taiji | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 天聰汗 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 天聪汗 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Names and titles

It is unclear whether "Hong Taiji" was a title or a personal name. Written Hong taiji in Manchu, it was borrowed from the Mongolian title Khong Tayiji.[1] That Mongolian term was itself derived from the Chinese huang taizi 皇太子 ("crown prince", "imperial prince"), but in Mongolian it meant, among other things, something like "respected son".[2] Alternatively, historian Pamela Crossley argues that "Hung Taiji" was a title "of Mongolian inspiration" derived from hung, a word that appeared in other Mongolian titles at the time.[3] Early seventeenth-century Chinese and Korean sources rendered his name as "Hong Taiji" (洪台極).[4] The modern Chinese rendering "Huang Taiji" (皇太極), which uses the character huang ("imperial"), misleadingly implies that Hong Taiji once held the title of "imperial prince" or heir apparent, even though his father and predecessor Nurhaci never designated a successor.[5]

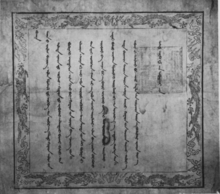

"Hong Taiji" was very rarely used in Manchu sources, because they observed a taboo on the personal names of emperors. In redacted documents, Hong Taiji was simply called the "Fourth Beile" or "fourth prince" (duici beile), indicating that he was the fourth ranked among the eight beile Nurhaci had designated from among his sons.[6] However, an archival document rediscovered in 1996 and recounting events from 1621 calls him "Hong Taiji" in a discussion concerning the possible naming of Nurhaci's heir apparent, a title that the document refers to as taise.[7] Tatiana Pang and Giovanni Stary, two specialists of early Manchu history, consider this document as "further evidence" that Hong Taiji was his real name, "not being at all connected with the Chinese title huang taizi".[7] Historian Mark Elliott views this as persuasive evidence that Hong Taiji was not a title, but a personal name.[8]

Western scholars used to refer to Hong Taiji as "Abahai", but this appellation is now considered mistaken.[9] Hong Taiji was never mentioned under this name in Manchu and Chinese sources; it was a mistake first made by Russian clergyman G.V. Gorsky and later repeated by sinologists starting in the early twentieth century.[10] Giovanni Stary states that this name may have originated by confusing "Abkai" with Abkai sure, which was Hong Taiji's era name in the Manchu language.[11] Though "Abahai" is indeed "unattested in Manchu sources", it might also have derived from the Mongol word Abaġai, an honorary name given to the younger sons of hereditary monarchs.[12] According to another view, Hong Taiji was mistakenly referred to as Abahai as a result of a confusion with the name of Nurhaci's main consort Lady Abahai.

Hong Taiji was first Khan of the Later Jin and then Emperor of the Qing dynasty, after he changed its name. His title as Great Khan was Bogd Sécén Khaan (Manchu: Gosin Onco Hūwaliyasun Enduringge Han). His reign names, which were used in his lifetime to record dates, were Tiancong 天聰 ("heavenly wisdom"; Manchu: Abka-i sure) from 1627 to 1636, and Chongde 崇德 ("lofty virtue"; Manchu: Wesihun erdemungge, Mongolian: Degedü Erdemtü) from 1636 to 1643.

Hong Taiji's temple name, by which he was worshipped at the Imperial Ancestral Temple, was Taizong 太宗, the name that was conventionally given to the second emperor of a dynasty.[13] His posthumous name, which was chosen to reflect his style of rule, was "Wen Huangdi" 文皇帝 (Manchu: šu hūwangdi), which means "the culturing emperor" or "the emperor of letters".[14][note 1]

Consolidation of power

Hong Taiji was the eighth son of Nurhaci, whom he succeeded as the second ruler of the Later Jin dynasty in 1626. Although it was always thought of as gossip, he was said to be involved in the suicide of Prince Dorgon's mother, Lady Abahai in order to block the succession of his younger brother. This is speculated because at the time of Nurhaci's death, there were four Lords/Beile with Hong Taiji as the lowest rank, but also the most fit one. Originally, at the end of Nurhaci's reign, Hong Taiji got hold of the two White Banners, but after Lady Abahai's death, he switched his two banners with Dorgon and Dodo's two Yellow banners (Nurhaci gave his two Yellow Banners to the two). In the end, Hong Taiji had control over the two strongest/highest class banners- the Plain and Bordered Yellow Banners and the most influence. From there, he slowly got rid of his competitor's powers. Later, he would also receive the Plain Blue Banner from his fifth brother Manggūltai, which was the third strongest banner. Those three banners would officially become the Upper Three Banners during the early part of the Qing dynasty.

Ethnic policies

During his reign, Hong Taiji started recruitment of Han ethnicity officials. After a 1623 revolt, Nurhaci came to mistrust his Nikan (Manchu: ᠨᡳᡴᠠᠨ, means "Han people") followers so Hong Taiji began their assimilation into the country and government.

A mass marriage of Han Chinese officers and officials to Manchu women numbering 1,000 couples was arranged by Prince Yoto and Hong Taiji in 1632 to promote harmony between the two ethnic groups.[15]

It is the predecessor of Mongol Yamen (ᠮᠣᠩᡤᠣ

ᠵᡠᡵᡤᠠᠨ 蒙古衙門, monggo jurgan) which was established for indirect government of Inner Mongolia after the Mongols were conquered by Hong Taiji. In 1638 it was renamed to Lifanyuan. Initially, the ministerial affairs were settled, while vice-ministers were set up as vice-ministers.[16]

Expansion

He continued the expansion of the state in the region later known as Manchuria, pushing deeper into Mongolia and raiding Korea and Ming China. His personal military abilities were widely praised and he effectively developed the military-civil administration known as the Eight Banners or Banner system. This system was well-suited to accept the different peoples, primarily Chinese and Mongols, who joined the Manchu state either following negotiated agreements or military defeat.

Although Hong Taiji patronized Tibetan Buddhism in public, in private he disdained the Buddhist belief of the Mongols and thought it was destructive of Mongol identity. He is quoted to have said that, "The Mongolian princes are abandoning the Mongolian language; their names are all in imitation of the lamas."[17] The Manchus themselves such as Hong Taiji did not personally believe in Tibetan Buddhism and few wanted to convert. Hong Taiji described some Tibetan Buddhist lamas as "incorrigibles" and "liars",[18] but still patronized Buddhism in order to harness the Tibetans' and Mongols' belief in the religion.[19]

Hong Taiji started his conquest by subduing the potent Ming ally in Korea. February 1627 his forces crossed the Yalu River which had frozen.[20] In 1628, he attempted to invade China, but was defeated by Yuan Chonghuan and his use of artillery.[20] During the next five years, Hong Taiji spent resources in training his artillery to offset the strength of the Ming artillery.

Hong Taiji upgraded the weapons of the Empire. He realized the advantage of the Red Cannons and later also bought the Red Cannons into the army. Though the Ming dynasty still had more cannons, Hong Taiji now possessed the cannons of equal might and Asia's strongest cavalry. Also during this time, he sent several probing raids into northern China which were defeated. First attack went through the Jehol Pass, then in 1632 and 1634 he sent raids into Shanxi.[20]

In 1636, Hong Taiji invaded Joseon Korea (see the Second Manchu invasion of Korea), as the latter did not accept that Hong Taiji had become emperor and refused to assist in operations against the Ming.[20] With the Joseon dynasty surrendered in 1637, Hong Taiji succeeded in making them cut off relations with the Ming dynasty and force them to submit as tributary state of the Qing Empire. Also during this period, Hong Taiji took over Inner Mongolia in three major wars, each of them victorious. From 1636 until 1644, he sent 4 major expeditions into the Amur region.[20] In 1640 he completed the conquest of the Evenks, when he defeated and captured their leader Bombogor. By 1644, the entire region was under his control.[20]

Huang Taji's plan at first was to make a deal with the Ming dynasty. If the Ming was willing to give support and money that would be beneficial to the Qing's economy, the Qing in exchange would not only be willing to not attack the borders, but also admit itself as a country one level lower than the Ming dynasty; however, since Ming court officials were reminded of the deal that preceded the Song dynasty's wars with the Jin Empire, the Ming refused the exchange. Huang Taiji rejected the comparison, saying that, "Neither is your Ming ruler a descendant of the Song nor are we heir to the Jin. That was another time."[21] Hong Taiji had not wanted to conquer the Ming. The Ming's refusal ultimately led him to take the offensive. The people who first encouraged him to invade China were his Han Chinese advisors Fan Wencheng, Ma Guozhu, and Ning Wanwo.[22] Hong Taiji recognized that the Manchus needed Han Chinese defectors in order to assist in the conquest of the Ming, and thus explained to other Manchus why he also needed to be lenient to recent defectors like Ming general Hong Chengchou, who surrendered to the Qing in 1642.[19]

Government

When Hong Taiji came into power, the military was composed of entirely Mongol and Manchu companies. By 1636, Hong Taiji created the first of many Chinese companies. Before the conquest of China, the number of companies organized by him and his successor was 278 Manchu, 120 Mongol, and 165 Chinese.[23] By the time of Hong Taiji's death there were more Chinese than Manchus and he had realized the need for there to be control exerted whilst getting approval from the Chinese majority. Not only did he incorporate the Chinese into the military, but also into the government. The Council of Deliberative Officials was formed as the highest level of policy-making and was composed entirely of Manchu. However, Hong Taiji adopted from the Ming such institutions as the Six Ministries, the Censorate and others.[23] Each of these lower ministries was headed by a Manchu prince, but had four presidents: two were Manchu, one was Mongol, and one was Chinese. This basic framework remained, even though the details fluctuated over time, for some time.[23]

The change from Jin to Qing

In 1635, Hong Taiji changed the name of his people from Jurchen (Manchu: ![]()

![]()

The dynastic name Later Jin was a direct reference to the Jin dynasty founded by the Jurchen people, who ruled northern China from 1115 to 1234. As such, the name was likely to be viewed as closely tied to the Jurchens and would perhaps evoke hostility from Chinese who viewed the Song dynasty, rival state to the Jin, as the legitimate rulers of China at that time. Hong Taiji's ambition was to conquer China proper and overthrow the Ming dynasty, and to do that required not only a powerful military force but also an effective bureaucratic administration. For this, he used the obvious model, that of the Ming government, and recruited Ming officials to his cause. If the name of Later Jin would prove an impediment to his goal among many Chinese, then it was not too much to change it. At the same time, Hong Taiji conquered the territory north of Shanhai pass by Ming Dynasty and Ligdan Khan in Inner Mongolia. He won one of the Yuan Dynasty's imperial jade seal (Chinese: 制誥之寶)[24] and a golden Buddha called "Mahakala".[25] In April 1636, Mongol nobility of Inner Mongolia, Manchu nobility and the Han mandarin held the Kurultai in Shenyang, recommended khan of Later Jin to be the emperor of Great Qing empire.[26][27] Russian archive contains translations of the 1636 year Hong Taiji decree with the provision that after the fall of the Qing dynasty Mongols will return to their previous laws, i.e. independence [28] Whatever the precise motivation, Hong Taiji proclaimed the establishment of the Qing dynasty and also changed his era name to Chóngdé in 1636.[20] The reasons for the choice of Qing as the new name are likewise unclear, although it has been speculated that the sound – Jin and Qing are pronounced similarly in Manchu – or wuxing theory – traditional ideas held that fire, associated with the character for Ming, was overcome by water, associated with the character for Qing – may have influenced the choice. Another possible reason may be that Hong Taiji changed the name of the dynasty from (Later) Jin to Qing in 1636 because of internecine fraternal struggle and skirmish between brothers and half brothers for the throne.

According to Taoist philosophy, the name Jin has the meaning of metal and fire in its constituent, thereby igniting the tempers of the brothers of the Manchu Royal household into open conflicts and wars. Hong Taiji therefore adopted the new name of Great Qing (大清), the Chinese character of which has the water symbol [3 strokes] on its left hand side. The name, which means clear and transparent, with its water symbol was hoped to put out the feud among the brothers of the Manchu Royal household.

The banners status

Before Hong Taiji was emperor, he controlled the two White banners. Upon Nurhaci's death, Hong Taiji immediately switched his two White Banners with Nurhaci's two Yellow Banners, which should have been passed on to Dorgon and his brothers. As emperor, he was the holder of three banners out of eight. He controlled the Upper Three Banners or the Elite banners which at the time were the Plain/Bordered Yellow Banners and Plain Blue Banner. Later the Plain Blue Banner was switched by Dorgon to the Plain White Banner as the third Elite Banner. At the end of his reign, Hong Taiji gave the two Yellow Banners to his eldest son Hooge. Daisan, who was the second son of Nurhaci, and his son controlled the two Red Banners. Dorgon and his two brothers controlled the two White Banners and Šurhaci's son Jirgalang controlled the remaining Bordered Blue Banner.

Death and succession

Hong Taiji died on 21 September 1643 just as the Qing was preparing to attack Shanhai Pass, the last Ming fortification guarding access to the north China plains.[29][note 2] Because he died without having named an heir, the Qing state now faced a succession crisis.[31] The Deliberative Council of Princes and Ministers debated on whether to grant the throne to Hong Taiji's half-brother Dorgon – a proven military leader – or to Hong Taiji's eldest son Hooge. As a compromise, Hong Taiji's five-year-old ninth son Fulin was chosen, while Dorgon – alongside Nurhaci's nephew Jirgalang – was given the title of "prince regent".[32] Fulin was officially crowned emperor of the Qing dynasty on 8 October 1643 and it was decided that he would reign under the era name "Shunzhi."[33] A few months later, Qing armies led by Dorgon seized Beijing, and the young Shunzhi Emperor became the first Qing emperor to rule from that new capital.[34] That the Qing state succeeded not only in conquering China but also in establishing a capable administration was due in large measure to the foresight and policies of Hong Taiji. His body was buried in Zhaoling, located in northern Shenyang.

Legacy

As the emperor, he is commonly recognized as having abilities similar to the best emperors such as Yongle, Emperor Taizong of Tang because of his effective rule, effective use of talent, and effective warring skills. According to half historian and half writer Jin Yong, Hong Taiji had the broad and wise views of Qin Shi Huang, Emperor Gaozu of Han, Emperor Guangwu of Han, Emperor Wen of Sui, Emperor Taizong of Tang, Emperor Taizu of Song, Kublai Khan, the Hongwu Emperor, and the Yongle Emperor. His political abilities were paralleled only by Genghis Khan, Emperor Taizong of Tang, and Emperor Guangwu of Han. In this sense, Hong Taiji is considered by some historians as the true first emperor for the Qing dynasty. Some historians suspect Hong Taiji was overall underrated and overlooked as a great emperor because he was a Manchu.

Family

- Father: Nurhaci, Taizu (太祖 努爾哈赤; 8 April 1559 – 30 September 1626)

- Grandfather: Taksi, Xianzu (顯祖 塔克世; 1543–1583)

- Grandmother: Empress Xuan, of the Hitara clan (宣皇后 喜塔臘氏; d. 1569), personal name Emeci (額穆齊)

- Mother: Empress Xiao Ci Gao, of the Yehe Nara clan (孝慈高皇后 葉赫那拉氏; 1575 – 31 October 1603), personal name Monggo Jerjer (孟古哲哲)

- Grandfather: Yangginu (楊吉努; d. 1584), held the title of a third rank prince (貝勒)

- Consorts and Issue:

- Primary consort, of the Niohuru clan (元妃 鈕祜祿氏; 1593–1612)

- Lobohoi (洛博會; 1611–1617), third son

- Primary consort, of the Ula Nara clan (繼妃 烏拉那拉氏)

- Hooge, Prince Suwu of the First Rank (肅武親王 豪格; 16 April 1609 – 4 May 1648), first son

- Loge (洛格; 1611 – November/December 1621), second son

- Princess Aohan of the First Rank (敖漢固倫公主; 3 April 1621 – 1654), first daughter

- Married Bandi (班第; d. 1647) of the Aohan Borjigit clan on 25 May 1633

- Empress Xiao Duan Wen of the Khorchin Borjigit clan (孝端文皇后 博爾濟吉特氏; 31 May 1599 – 28 May 1649), personal name Jerjer (哲哲)

皇后..皇太后- Princess Wenzhuang of the First Rank (固倫溫莊公主; 1625–1663), personal name Makata (馬喀塔), second daughter

- Married Ejei (d. 1641) of the Chahar Borjigit clan on 16 February 1636

- Married Abunai (阿布奈; 1635–1675) of the Chahar Borjigit clan in 1645, and had issue (two sons)

- Princess Jingduan of the First Rank (固倫靖端公主; 2 August 1628 – June/July 1686), third daughter

- Married Kitad (奇塔特; d. 1653) of the Khorchin Borjigit clan in 1639

- Princess Yong'an Duanzhen of the First Rank (固倫永安端貞公主; 7 October 1634 – February/March 1692), eighth daughter

- Married Bayasihulang (巴雅斯護朗) of the Khorchin Borjigit clan in 1645

- Princess Wenzhuang of the First Rank (固倫溫莊公主; 1625–1663), personal name Makata (馬喀塔), second daughter

- Consort Zhuang, of the Khorchin Borjigit clan (莊妃). Her posthumous name is Empress Xiao Zhuang Wen (孝莊文皇后 博爾濟吉特氏; 28 March 1613 – 27 January 1688), personal name Bumbutai (布木布泰). She was an empress dowager during the reign of Shunzhi Emperor by title Empress Dowager Zhaosheng.

莊妃..昭聖皇太后→昭聖太皇太后- Princess Yongmu of the First Rank (固倫雍穆公主; 31 January 1629 – February/March 1678), personal name Yatu (雅圖), fourth daughter

- Married Birtakhar (弼爾塔哈爾; d. 1667) of the Khorchin Borjigit clan in 1641

- Princess Shuhui of the First Rank (固倫淑慧公主; 2 March 1632 – 28 February 1700), personal name Atu (阿圖), fifth daughter

- Married Suo'erha (索爾哈) of the Khalkha Borjigit clan in 1643

- Married Sabdan (色布騰; d. 1667) of the Barin Borjigit clan in 1648

- Princess Shuzhe Duanxian of the First Rank (固倫淑哲端獻公主; 16 December 1633 – 1648), seventh daughter

- Married Lamasi (喇瑪思) of the Jarud Borjigit clan in 1645

- Fulin, the Shunzhi Emperor (世祖 福臨; 15 March 1638 – 5 February 1661), ninth son

- Princess Yongmu of the First Rank (固倫雍穆公主; 31 January 1629 – February/March 1678), personal name Yatu (雅圖), fourth daughter

- Primary consort Minhui, of the Khorchin Borjigit clan (敏惠元妃 博爾濟吉特氏; 1609 – 22 October 1641), personal name Harjol (海蘭珠)

宸妃- Eighth son (27 August 1637 – 13 March 1638)

- Noble Consort Yijing, of the Abaga Borjigit clan (懿靖貴妃 博爾濟吉特氏; d. 1674), personal name Namuzhong (娜木鐘)

貴妃..懿靖貴妃- Princess Duanshun of the First Rank (固倫端順公主; 30 April 1636 – July/August 1650), 11th daughter

- Married Garma Sodnam (噶爾瑪索諾木; d. 1663) of the Abaga Borjigit clan in December 1647 or January 1648

- Bomubogor, Prince Xiangzhao of the First Rank (襄昭親王 博穆博果爾; 20 January 1642 – 22 August 1656), 11th son

- Princess Duanshun of the First Rank (固倫端順公主; 30 April 1636 – July/August 1650), 11th daughter

- Consort Kanghuishu, of the Abaga Borjigit clan (康惠淑妃 博爾濟吉特氏), personal name Batemazao (巴特瑪璪)

淑妃..康惠淑妃 - Secondary consort, of the Yehe Nara clan (側福晉 葉赫那拉氏)

- Šose, Prince Chengzeyu of the First Rank (承澤裕親王 碩塞; 17 January 1629 – 12 January 1655), fifth son

- Secondary consort, of the Jarud Borjigit clan (側福晉 博爾濟吉特氏)

- Princess of the First Rank (固倫公主; 15 December 1633 – April/May 1649), sixth daughter

- Married Kuazha (誇札; d. 1649) of the Manchu Irgen Gioro clan in December 1644 or January 1645

- Ninth daughter (5 November 1635 – April/May 1652)

- Married Hashang (哈尚; d. 1651) of the Mongol Borjigit clan in October/November 1648

- Princess of the First Rank (固倫公主; 15 December 1633 – April/May 1649), sixth daughter

- Mistress, of the Yanja clan (顏扎氏)

- Yebušu, Duke of the Second Rank (輔國公 葉布舒; 25 November 1627 – 23 October 1690), fourth son

- Mistress, of the Nara clan (那拉氏)

- Lady of the Second Rank (縣君; 1635 – August/September 1661), tenth daughter

- Married Huisai (輝塞; d. 1651) of the Manchu Gūwalgiya clan in September/October 1651

- Gose, Duke Quehou of the First Rank (鎮國愨厚公 高塞; 12 March 1637 – 5 September 1670), sixth son

- 13th daughter (16 August 1638 – May/June 1657)

- Married Laha (拉哈) of the Manchu Gūwalgiya clan in March/April 1652

- Lady of the Second Rank (縣君; 1635 – August/September 1661), tenth daughter

- Mistress, of the Sayin Noyan clan (賽音諾顏氏)

- Lady of the Third Rank (鄉君; 9 April 1637 – November/December 1678), 12th daughter

- Married Bandi (班迪; d. 1700) of the Mongol Borjigit clan in September/October 1651

- Lady of the Third Rank (鄉君; 9 April 1637 – November/December 1678), 12th daughter

- Mistress, of the Irgen Gioro clan (伊爾根覺羅氏)

- Cangšu, Duke of the Second Rank (輔國公 常舒; 13 May 1637 – 13 February 1700), seventh son

- Mistress, of the Keyikelei clan (克伊克勒氏)

- Toose, Duke of the Second Rank (輔國公 韜塞; 12 March 1639 – 23 March 1695), tenth son

- Mistress, of the Cilei clan (奇壘氏; d. 1645)

- Princess Kechun of the Second Rank (和碩恪純公主; 7 January 1642 – 1704), 14th daughter

- Married Wu Yingxiong (1634–1675) on 9 October 1653, and had issue (three sons, one daughter)

- Princess Kechun of the Second Rank (和碩恪純公主; 7 January 1642 – 1704), 14th daughter

- Primary consort, of the Niohuru clan (元妃 鈕祜祿氏; 1593–1612)

Popular culture

- Portrayed by Liu Dekai in the 2003 TV series Xiaozhuang Mishi.

- Portrayed by Jiang Wen in the 2006 TV series Da Qing Fengyun.

- Portrayed by Hawick Lau in the 2012 TV series In Love With Power.

- Portrayed by Nam Kyung-eub in the 2013 jTBC TV series Blooded Palace: The War of Flowers.

- Portrayed by Byun Joo-hyun in the 2014 tvN TV series The Three Musketeers.

- Portrayed by Jung Sung-woon in the 2015 MBC TV series Hwajung.

- Portrayed by Raymond Lam in the 2017 TV series Rule the World

- Portrayed by Kim Beob-rae in the 2017 film The Fortress.

See also

- Chinese emperors family tree (late)

- Qing conquest of the Ming

- Daily life in the Forbidden City, Wan Yi, Wang Shuqing, Lu Yanzhen. ISBN 0-670-81164-5.

- Qing imperial genealogy(清皇室四譜).

- Qing dynasty Taizong’s veritable records《清太宗實錄》

- Royal archives of the Qing dynasty (清宮档案).

- Samjeondo Monument

Notes

- Hong Taiji's complete posthumous name was much longer:

- 1643: Yingtian xingguo hongde zhangwu kuanwen rensheng ruixiao Wen Emperor (應天興國弘德彰武寬溫仁聖睿孝文皇帝)

- 1662: Yingtian xingguo hongde zhangwu kuanwen rensheng ruixiao longdao xiangong Wen Emperor (應天興國弘德彰武寬溫仁聖睿孝隆道顯功文皇帝)

- Longdao xiangong 隆道顯功 ("prosperous way and manifestation of might") was added

- 1723: Yingtian xingguo hongde zhangwu kuanwen rensheng ruixiao jingmin longdao xiangong Wen Emperor (應天興國弘德彰武寬溫仁聖睿孝敬敏隆道顯功文皇帝)

- Jingmin 敬敏 ("reverent and diligent") was added

- 1735: Yingtian xingguo hongde zhangwu kuanwen rensheng ruixiao jingmin zhaoding longdao xiangong Wen Emperor (應天興國弘德彰武寬溫仁聖睿孝敬敏昭定隆道顯功文皇帝)

- Zhaoding 昭定 ("illustrious stability") was added

- Most sources give the date of Hong Taiji's death on September 21 (Chongde 崇德 8.8.9); however others give the date as September 9.[30]

References

Citations

- Rawski 1998, p. 50 ("probably a rendition of the Mongol noble title, Khongtaiji"); Pang & Stary 1998, p. 13 ("of Mongolian origin"); Elliott 2001, p. 397, note 71 (Khong tayiji was "quite common among the Mongols, from whom the Jurchens borrowed it").

- Elliott 2001, p. 397, note 71 (Khong tayiji as "meaning loosely 'Respected Son'"); Miyawaki 1999, p. 330 (derivation from huang taizi and other meaning as "viceroy").

- Crossley 1999, p. 165, note 82.

- Crossley 1999, pp. 164–65.

- Pang & Stary 1998, p. 13 (""Nurhaci never assigned him to such position"); Crossley 1999, p. 165 ("this ['imperial prince', 'heir apparent'] is certainly not what his name meant"); Elliott 2001, p. 397, note 71 ("Huang Taiji" gives the "mistaken impression that he was a crown prince").

- Crossley 1999, p. 164.

- Pang & Stary 1998, p. 13.

- Elliott 2001, p. 397, note 71 ("that Hong (not Hung) Taiji was indeed his given name, and not a title, is persuasively established on the basis of new documentary evidence in Tatiana A. Pang and Giovanni Stary...").

- Stary 1984; Crossley 1999, p. 165; Elliott 2001, p. 396, note 71.

- Stary 1984, pp. 298–99.

- Stary 1984, p. 299.

- Grupper 1984, p. 69.

- Wilkinson 2012, pp. 270 and 806.

- Crossley 1999, pp. 137 and 165.

- ed. Walthall 2008, p. 148.

- Pamela Kyle Crossley (February 15, 2000). A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology. University of California Press. pp. 214–. ISBN 978-0-520-92884-8.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 203

- The Cambridge History of China: Pt. 1 ; The Ch'ing Empire to 1800. Cambridge University Press. 1978. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-0-521-24334-6.

- The Cambridge History of China: Pt. 1 ; The Ch'ing Empire to 1800. Cambridge University Press. 1978. pp. 65–. ISBN 978-0-521-24334-6.

- Dupuy & Dupuy 1986, p. 592

- Wakeman 1985, p. 205.

- Wakeman 1985, p. 204.

- Schirokauer 1978, pp. 326–327

- "In Japanese:その後の「制誥之寶」とマハーカーラ像". 宣和堂遺事 宣和堂の節操のない日記. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- 清太宗實錄 "Qing Taizong shilu" Part 20

- Marriage and inequality in Chinese society By Rubie Sharon Watson, Patricia Buckley Ebrey, p.177

- Tumen jalafun jecen akū: Manchu studies in honour of Giovanni Stary By Giovanni Stary, Alessandra Pozzi, Juha Antero Janhunen, Michael Weiers

- Kuzmin S.L. and Batsaikhan O. On the decree of the Hong taiji (Abahai) emperor on the restoration of independence of the Mongols after the fall of the Qing Dynasty. – Vostok (Oriens), 2019, no 5, pp. 200-217..

- Oxnam 1975, p. 38; Wakeman 1985, p. 297; Gong 2010, p. 51

- Dennerline 2002, p. 74

- Roth Li 2002, p. 71.

- Dennerline 2002, p. 78.

- Fang 1943, p. 255.

- Wakeman 1985, pp. 313–315 and 858.

Works cited

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle (1999), A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-21566-4

- Dennerline, Jerry (2002). "The Shun-chih Reign". In Peterson, Willard J. (ed.). Cambridge History of China, Vol. 9, Part 1: The Ch'ing Dynasty to 1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Pressv. pp. 73–119. ISBN 0-521-24334-3.

- Dupuy, R. Ernest; Dupuy, Trevor N. (1986). The Encyclopedia of Military History from 3500 B.C. to the Present (2nd Revised ed.). New York, NY: Harper & Row, Publishers. ISBN 0-06-181235-8.

- Fang, Chao-ying (1943). "Fu-lin". In Hummel, Arthur W. (ed.). Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period (1644–1912). Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office. pp. 255–59.

- Elliott, Mark C. (2001), The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China, Stanford: Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-4684-2

- Gong, Baoli 宫宝利, ed. (2010). Shunzhi shidian 顺治事典 ["Events of the Shunzhi reign"] (in Chinese). Beijing: Zijincheng chubanshe 紫禁城出版社 ["Forbidden City Press"]. ISBN 978-7-5134-0018-3.

- Grupper, Samuel M. (1984). "Manchu Patronage and Tibetan Buddhism During the First Half of the Ch'ing Dynasty" (PDF). The Journal of the Tibet Society (4): 47–75. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016.

- Miyawaki, Junko (1999). "The Legitimacy of Khanship among the Oyirad (Kalmyk) Tribes in Relation to the Chinggisid Principle". In Reuven Amitai-Preiss; David O. Morgan (eds.). The Mongol Empire and its Legacy. Leiden: Brill. pp. 319–31. ISBN 90-04-11946-9.

- Oxnam, Robert B. (1975). Ruling from Horseback: Manchu Politics in the Oboi Regency, 1661–1669. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-64244-5.

- Pang, Tatiana A.; Giovanni Stary (1998). New Light on Manchu Historiography and Literature: The Discovery of Three Documents in Old Manchu Script. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 3-447-04056-4.

- Rawski, Evelyn S. (1991). "Ch'ing Imperial Marriage and Problems of Rulership". In Watson, Rubie S.; Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (eds.). Marriage and Inequality in Chinese Society. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 170–203. ISBN 0-520-06930-7.

- ——— (1998). The Last Emperors: A Social History of Qing Imperial Institutions. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22837-5.

- Roth Li, Gertrude (2002). "State Building before 1644". In Willard J. Peterson (ed.). Cambridge History of China, Vol. 9, Part 1: The Ch'ing Dynasty to 1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 9–72. ISBN 0-521-24334-3.

- Schirokauer, Conrad (1978). A Brief History of Chinese and Japanese Civilizations. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 0-15-505570-4.

- Stary, Giovanni (1984). (subscription required). "The Manchu Emperor "Abahai": Analysis of an Historiographic Mistake". Central Asiatic Journal. 28 (3–4): 296–299. JSTOR 41927447.

- Wakeman, Frederic, Jr. (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-Century China. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04804-0.

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2012). Chinese History: A New Manual. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-06715-8.

- Zhao, Erxun 趙爾巽; et al. (1927). Qingshi gao 清史稿 [Draft History of Qing]. Citing from 1976–77 edition by Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, in 48 volumes with continuous pagination.

Further reading

- di Cosmo, Nicola (2004). "Did Guns Matter? Firearms and the Qing Formation". In Lynn A. Struve (ed.). The Qing Formation in World-Historical Time. Cambridge (MA) and London: Harvard University Press. pp. 121–166. ISBN 0-674-01399-9.

- Elliott, Mark (2005). "Whose Empire Shall It Be? Manchu Figurations of Historical Process in the Early Seventeenth Century: East Asia from Ming to Qing". In Lynn A. Struve (ed.). Time, Temporality, and Imperial Transition. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. pp. 31–72. ISBN 0-8248-2827-5.

Hong Taiji Born: 28 November 1592 Died: 21 September 1643 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Nurhaci |

Khan of Later Jin 1626–1636 |

Qing dynasty was established in 1636. Himself became the Emperor of the Qing dynasty. |

| New title Qing dynasty was established in 1636 |

Emperor of the Qing dynasty 1636–1643 |

Succeeded by Shunzhi Emperor |