Siege of Fort Zeelandia

The Siege of Fort Zeelandia of 1661–1662 ended the Dutch East India Company's rule over Taiwan and began the Kingdom of Tungning's rule over the island. Taiwanese scholar Lu Chien-jung described this event as "a war that determined the fate of Taiwan in the four hundred years that followed".

Prelude

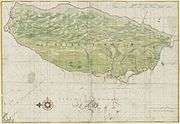

From 1623 to 1624 the Dutch had been at war with Ming China over the Pescadores. In 1633 they clashed with a fleet led by Zheng Zhilong in the Battle of Liaoluo Bay, ending in Dutch defeat. By 1632 the Dutch had established a post on a peninsula named Tayoan (now Anping District of Tainan), which was separated from the main part of Formosa by a shallow lagoon historically referred to as the Taikang inland sea. The Dutch fortifications consisted of two forts along the bay: the first and main fortification was the multiple-walled Fort Zeelandia, situated at the entrance to the bay,[7] while the second was the smaller Fort Provintia, a walled administrative office.[8] Frederick Coyett, the governor of Taiwan for the Dutch East India Company, was stationed in Fort Zeelandia with 1,800 men, while his subordinate, Valentyn, was in charge of Fort Provintia and its garrison of 500 men.

In 1659, after an unsuccessful attempt to capture Nanjing, Koxinga, son of Zheng Zhilong and leader of the Ming loyalist remnants, felt that the Qing Empire had consolidated their position in China sufficiently, while his troops needed more supplies and manpower. He began searching for a suitable location as his base of operations, and soon a Chinese man named He Bin (Chinese: 何斌), who was working for the Dutch East India Company in Formosa (Taiwan), fled to Koxinga's base in Xiamen and provided him with a map of Taiwan.[9]

The siege

On 23 March 1661, Koxinga's fleet set sail from Kinmen (Quemoy) with hundreds of junks of various sizes, with roughly 25,000 soldiers and sailors aboard. They arrived at Penghu the next day. On 30 March, a small garrison was left at Penghu while the main body of the fleet left and arrived at Tayoan on April 2. On Baxemboy Island in the Bay of Taiwan, unrelated to the siege, 2,000 Chinese attacked 240 Dutch musketeers, routing them.[3] After passing through a shallow waterway unknown to the Dutch, they landed at the bay of Lakjemuyse.[11] Four Dutch ships attacked the Chinese junks and destroyed several but one of their own squadron was burnt by fire boats. The rest escaped from the harbor, two to return, while the third sailed for Batavia, not reaching her destination until after some fifty days owing to the south monsoon. No further opposition was for the time encountered. The remainder of Koxinga's men were safely landed and built earthworks overlooking the plain.

"Some were armed with bows and arrows hanging down their backs ; others had nothing save a shield on the left arm and a good sword in the right hand ; while many wielded with both hands a formidable battle-sword fixed to a stick half the length of a man. Everyone was protected over the upper part of the body with a coat of iron scales, fitting below one another like the slates of a roof; the arms and legs being left bare. This afforded complete protection from rifle bullets and yet left ample freedom to move, as those coats only reached down to the knees and were very flexible at all the joints. The archers formed Koxinga's best troops, and much depended on them, for even at a distance they contrived to handle their weapons with so great skill that they very nearly eclipsed the riflemen. The shield bearers were used instead of cavalry. Every tenth man of them is a leader, who takes charge of, and presses his men on, to force themselves into the ranks of the enemy. With bent heads and their bodies hidden behind the shields, they try to break through the opposing ranks with such fury and dauntless courage as if each one had still a spare body left at home. They continually press onwards, notwithstanding many are shot down ; not stopping to consider, but ever rushing forward like mad dogs, not even looking round to see whether they are followed by their comrades or not. Those with the sword-sticks—called soapknives by the Hollanders—render the same service as our lancers in preventing all breaking through of the enemy, and in this way establishing perfect order in the ranks ; but when the enemy has been thrown into disorder, the Sword-bearers follow this up with fearful massacre amongst the fugitives.

"Koxinga was abundantly provided with cannons and ammunition . . He had also two companies of 'Black-boys,' many of whom had been Dutch slaves and had learned the use of the rifle and musket-arms. These caused much harm during the war in Formosa."[12][13]

The latter courageously marched in rows of twelve men towards the enemy, and when they came near enough, they charged by firing three volleys uniformly. The enemy, not less brave, discharged so great a storm of arrows that they seemed to darken the sky. From both sides some few fell hors de combat, but still the Chinese were not going to run away, as was imagined. The Dutch troops now noticed the separated Chinese squadron which came to surprise them from the rear; and seeing that those in front stubbornly held their ground, it now became a case of sero sapiunt Phryges. They now discovered that they had been too confident of the weakness of the enemy, and had not anticipated such resistance. If they were courageous before the battle (seeking to emulate the actions of Gideon), fear now took the place of their courage, and many of them threw down their rifles without even discharging them at the enemy. Indeed, they took to their heels, with shameful haste, leaving their brave comrades and valiant Captain in the lurch. Pedel, judging that it would be the veriest folly to withstand such overwhelming numbers, wished to close together and retreat in good order, but his soldiers would not listen to him. Fear had the upper-hand, and life was dear to them; each therefore sought to save himself. The Chinese saw the disorder and attacked still more vigorously, cutting down all before them. They gave no quarter, but went on until the Captain with one hundred and eighteen of his army were slain on the field of battle, as a penalty for making light of the enemy. Other misfortunes befell this unhappy company. A large number of the rifles in possession of our troops were left behind. This battle was fought on a sandy plain, from which escape was impossible, and but for the proximity of the pilot-boat, which lay close to the shore, not one would have been left to tell the tale. The fugitives, who had to wade up to their throats in water, were conveyed to Tayouan.[14][15]

But it was observed that the greatest part of the hostile army—which, according to one of the prisoners, amounted to twenty thousand men, Koxinga himself being present—had already landed on the Sakam shore. To all appearance they would probably resist, pursue, and defeat us, seeing that they had a large force of cavalry, and were armed with rifles, soapknives, bows and arrows, and such like weapons, besides being harnessed and provided with storm-helmets.[16]

On April 4, Valentyn surrendered to Koxinga's army after it laid siege to Fort Provintia. The rapid assault had caught Valentyn unprepared since he was under the impression that the fort was under the protection of Fort Zeelandia. On April 7, Koxinga's army surrounded Fort Zeelandia, sending the captured Dutch priest Antonius Hambroek as emissary demanding the garrison's surrender. However, Hambroek urged the garrison to resist instead of surrender and was executed after returning to Koxinga's camp. Koxinga ordered his artillery to advance and used 28 cannons to bombard the fort.[17] Koxinga's fleet then began a massive bombardment; troops on the ground attempted to storm the fort, but were repulsed with considerable losses. Koxinga then changed his tactics and laid siege to the fort.

On the 28th of May, news of the siege reached Jakarta, and the Dutch East India Company dispatched a fleet of 10 ships and 700 sailors to relieve the fort. On July 5, the relief force arrived and engaged in small scale confrontations with Koxinga's fleet. On July 23, the two sides gave major battle as the Dutch fleet attempted to break Koxinga's blockade. A second, ultimately unsuccessful attempt at relief was mounted in October. The Dutch tried to bombard the Chinese position with their ships, but their shots were too high and missed their target, giving the Chinese gunners time to prepare and return fire. Meanwhile the smaller Dutch ships engaged the Chinese junks, which lured them into a narrow strait with a false withdrawal. The Dutch ships were unable to get away as the wind had died and they were forced to paddle their boats, but the Chinese caught them and massacred the crew on board and used pikes to kill those who jumped overboard. The Chinese caught Dutch grenades in nets and threw them back at the Dutch. The Dutch flagship Koukercken ran aground right in front of an enemy cannon placement and was sunk. Another ship was stranded and its crew fled to Fort Zeelandia. The remaining Dutch fleet was forced to retreat with two ships sunk, three smaller vessels captured, and 130 casualties.[6]

Coyet remarked on the accuracy of Chinese cannon bombardment against Dutch gun emplacements on the fort. Explosive landmines were used by Koxinga against Dutch musketeers.[18]

In October, several dozen Dutch troops raided a nearby island for provisions. The raid took a disastrous turn when they encountered a small group of Chinese soldiers. They tried to flee, but suffered heavy casualties, losing 36 men.[19]

In December, deserting German mercenaries brought Koxinga word of low morale among the garrison, and he launched a major assault on the fort, which was ultimately repelled.[20] In January 1662, a German sergeant named Hans Jurgen Radis defected to give Koxinga critical advice on how to capture the fortress from a redoubt whose strategic importance had gone hitherto unnoticed by the Chinese forces. Koxinga followed his advice and the Dutch redoubt fell within a day. This claim of a defector appears in a post hoc account of the siege written by Frederick Coyett, whom scholars have noted sought to absolve the author of responsibility for the defeat. A Swiss soldier also writes about the betrayal independently. Ming records make no mention of any defector or German named Hans Jurgen Radis.[20][21] Koxinga deployed cannons his uncle had dredged up years earlier from the sea.[22] The Ming dynasty had in the past dispatched work crews to salvage cannons from European shipwrecks and reverse engineer them.[23]

On 12 January 1662, Koxinga's fleet initiated another bombardment, while the ground force prepared to assault the fort. With supplies dwindling and no sign of reinforcement, Coyett finally ordered the hoisting of the white flag and negotiated terms of surrender, a process that was finalized on February 1. On the 9th of February, the remaining Dutch East India Company personnel left Taiwan; all were allowed to take with them their personal belongings, as well as provisions sufficient for them to reach the nearest Dutch settlement.[24]

Torture

Torture was used by both sides in the war. One Dutch physician carried out a vivisection on a Chinese prisoner.[25] The Chinese amputated the genitals, noses, ears, and limbs of Dutch prisoners while they were still alive and sent back the mutilated corpses and prisoners to the Dutch.[26] Chinese rebels had earlier cut the genitals, eyes, ears and noses of Dutch people in the Guo Huaiyi rebellion.[27] The mouths of Dutch soldiers were filled with their amputated genitals by the Chinese who also slammed nails into their bodies, and amputated their noses, legs and arms and sent the bodies of these Dutch soldiers back to the fort.[28]

Taiwanese Aborigines

The Taiwanese aboriginal tribes, who were previously allied with the Dutch against the Chinese during the Guo Huaiyi Rebellion in 1652, turned against the Dutch during the siege. They defected to Koxinga's Chinese forces.[29] The aboriginals (Formosans) of Sincan defected to Koxinga after he offered them amnesty. They proceeded to work for the Chinese in executing captured Dutchmen. On 17 May 1661, the frontier aboriginals in the mountains and plains also surrendered and defected to the Chinese. They celebrated their freedom from compulsory education under the Dutch rule by hunting down Dutch colonists and beheading them, while destroying their Christian school textbooks.[30] Koxinga formulated a plan to give oxen, farming tools, and teach farming techniques to the Taiwan Aboriginals. He gave them Ming gowns and caps, provided feasts for chieftains and gifted tobacco to Aboriginals who were gathered in crowds to meet and welcome him as he visited their villages after he defeated the Dutch.[31]

Aftermath

After arriving in Batavia, Coyett was imprisoned for three years and tried for high treason, for surrendering the post and the loss of valuable goods. After lobbying by friends and relatives he was partially pardoned in 1674, and exiled to the most eastern of the Banda Islands. He published Neglected Formosa (Dutch: 't Verwaerloosde Formosa) in 1675, a book in which he defended his actions in Taiwan and criticized the company for neglecting his pleas for reinforcement.

After the loss of the post at Tayoan, the Dutch East India Company mounted several attempts at recapture—even forming an alliance with the Qing Empire to defeat Koxinga's fleet. The alliance captured Keelung in northern Taiwan, but was forced to abandon it because of logistical difficulties and the inferiority of the Qing fleet when pitted against Koxinga's veteran sailors.

Dutch prisoners

During the Siege of Fort Zeelandia the Chinese took many Dutch prisoners, among them the Dutch missionary Antonius Hambroek and his wife, and two of their daughters. Koxinga sent Hambroek to Fort Zeelandia to persuade the garrison to surrender; if unsuccessful, Hambroek would be killed upon return. Hambroek went up to the Fort, where two of his other daughters still remained, and urged the garrison to not surrender. He subsequently returned to Koxinga's camp and was beheaded. Additionally, a rumor was spread among the Chinese that the Dutch were encouraging the native Taiwan aboriginals to kill Chinese. In retaliation, Koxinga ordered the mass execution of Dutch male prisoners,[32] mostly by crucifixion and decapitation[33] with a few women and children also being killed. The remainder of the Dutch women and children were enslaved, with Koxinga taking Hambroek's teenage daughter as his concubine (she was described by the Dutch commander Caeuw as "a very sweet and pleasing maiden", while other Dutch women were sold to Chinese soldiers to become their (secondary) wives or mistresses.[34][35][36] The daily journal of the Dutch fort recorded that "the best were preserved for the use of the commanders, and the rest were sold to the common soldiers. Happy was she that fell to the lot of an unmarried man, being thereby freed from vexations by the Chinese women, who are very jealous of their husbands."[37] The Chinese took Dutch women as slave concubines and wives and they were never freed: in 1684 some were reported to be still living. In Quemoy a Dutch merchant was contacted with an arrangement to release the prisoners which was proposed by a son of Koxinga's but it came to nothing.[38][39][40]

The Chinese taking Dutch women as concubines was featured in Joannes Nomsz's famous play "Antonius Hambroek, of de Belegering van Formoza" ("Antonius Hambroek, or the Siege of Formosa"), which documented European anxieties at the fate of the Dutch women and defeat by non-Europeans.[41]

Cultural influences

The battle was depicted in the movie The Sino-Dutch War 1661 (Chinese: 鄭成功1661), which ended in Koxinga's victory over the Dutch.

Gallery

Surrender of Fort Zeelandia

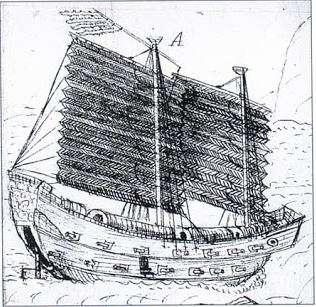

Surrender of Fort Zeelandia A Ming junk, 1637.

A Ming junk, 1637. A ship of the Tungning Kingdom.

A ship of the Tungning Kingdom. One of Koxinga's armored soldiers.

One of Koxinga's armored soldiers.- Statues of Koxinga and Dutch emissary at Chihkan Tower, the site where Fort Provintia once stood.

Painting of Fort Zeelandia in 1635, from The National Archives, The Hague, Netherlands

Painting of Fort Zeelandia in 1635, from The National Archives, The Hague, Netherlands "Antonius Hambroek, of de Belegering van Formoza"

"Antonius Hambroek, of de Belegering van Formoza"

References

- Clodfelter (2017), p. 63: "The whole force sent to Taiwan was 25,000 men, but only 6,000 advanced on Zeelandia."

- Manthorpe (2009), p. 65.

- Clodfelter (2017), p. 63.

- Clodfelter (2017), p. 63: "1,733 Dutch inhabitants of Fort Zeelandia, of which 905 were armed men."

- Clodfelter (2017), p. 63: Clodfelter states that Koxinga's army lost half its men.

- Andrade (2011), pp. 221–222.

- Davidson (1903), p. 13.

- Campbell (1903), p. 546.

- Andrade (2008), §15.

- Coyett (1903), pp. 455-456.

- Campbell (1903), p. 544.

- Struve (1993), p. 218.

- Campbell (1903), p. 420.

- Campbell (1903), pp. 416–417.

- Struve (1993), p. 216.

- Campbell (1903), p. 482.

- Davidson (1903), p. 38.

- Andrade (2011), pp. 240–241.

- Andrade (2016), p. 192.

- Andrade (2008).

- Struve (1998), p. 232.

- Andrade (2011), pp. 244–245.

- Andrade (2011), p. 308.

- Andrade 2011, p. 294.

- Ho, Dahpon David. Sealords live in vain : Fujian and the making of a maritime frontier in seventeenth-century China (A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Hi story). UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO.

- Andrade, Tonio (2011). "A Chinese Farmer,Two African Boys, and a Warlord:Toward a Global Microhistory". Journal of World History. University of Hawai'i Press. 21 (4).

- Andrade (2011), p. 125.

- Andrade (2011), p. 223.

- Covell (1998), pp. 96–97.

- Hsin-Hui, Chiu (2008). The Colonial 'civilizing Process' in Dutch Formosa: 1624 - 1662. Volume 10 of TANAP monographs on the history of the Asian-European interaction (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 222. ISBN 978-9004165076. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- Xing Hang (5 January 2016). Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720. Cambridge University Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-316-45384-1.

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1991). The Search for Modern China (illustrated, reprint ed.). W. W. Norton & Company. p. 55. ISBN 0393307808. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- Andrade (2011), p. 5.

- Wright, Arnold, ed. (1909). Twentieth century impressions of Netherlands India: Its history, people, commerce, industries and resources (illustrated ed.). Lloyd's Greater Britain Pub. Co. p. 67. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- Newman, Bernard (1961). Far Eastern Journey: Across India and Pakistan to Formosa. H. Jenkins. p. 169. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- Moffett, Samuel H. (1998). A History of Christianity in Asia: 1500-1900. Bishop Henry McNeal Turner Studies in North American Black Religion Series. 2. Orbis Books. p. 222. ISBN 1570754500. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- Manthorpe (2009), p. 77.

- Covell (1998), p. 96.

- Lach & Van Kley (1998), p. 1823.

- Manthorpe (2009), p. 72.

- Andrade (2011), p. 413.

Bibliography

- Andrade, Tonio (2008). "Chapter 11: The Fall of Dutch Taiwan". How Taiwan Became Chinese : Dutch, Spanish and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231128551.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Andrade, Tonio (2011). Lost Colony: The Untold Story of China's First Great Victory Over the West (illustrated ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691144559.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7

- Campbell, William (1903). Formosa under the Dutch: described from contemporary records, with explanatory notes and a bibliography of the island. London: Kegan Paul. OCLC 644323041.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clodfelter, M. (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015 (4th ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0786474707.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Covell, Ralph R. (1998). Pentecost of the Hills in Taiwan: The Christian Faith Among the Original Inhabitants (illustrated ed.). Hope Publishing House. ISBN 0932727905. Retrieved 10 December 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coyett, Frederick (1903) [First published 1675 in 't verwaerloosde Formosa]. "Arrival and Victory of Koxinga". In Campbell, William (ed.). Formosa under the Dutch: described from contemporary records, with explanatory notes and a bibliography of the island. London: Kegan Paul. pp. 412–459. LCCN 04007338.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davidson, James W. (1903). "Chapter III: Formosa under the Dutch 1644-1661". The island of Formosa, past and present: History, people, resources, and commercial prospects. Tea, camphor, sugar, gold, coal, sulphur, economical plants, and other productions. London and New York: Macmillan. LCCN 03022967. OL 6931635M.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lach, Donald F.; Van Kley, Edwin J. (1998). Asia in the Making of Europe: A Century of Advance : East Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226467694. Retrieved 28 June 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Manthorpe, Jonathan (2009). Forbidden nation : a history of Taiwan (1st Palgrave Macmillan pbk. ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0230614246.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Struve, Lynn A., ed. (1993). Voices from the Ming-Qing cataclysm: China in tigers' jaws. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300075537. Retrieved 28 June 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Library resources about Siege of Fort Zeelandia |