State of the Teutonic Order

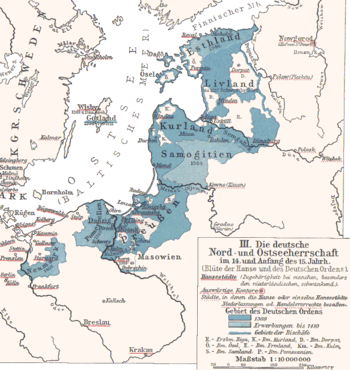

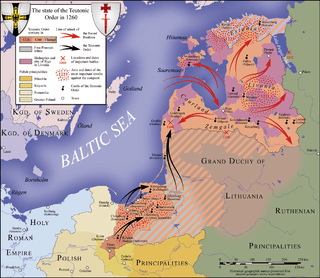

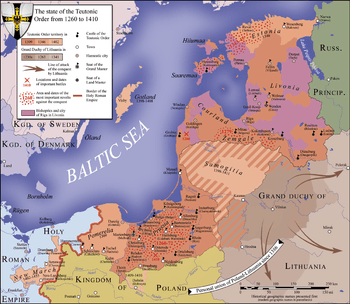

The State of the Teutonic Order (German: Staat des Deutschen Ordens; Latin: Civitas Ordinis Theutonici), also called Deutschordensstaat (German: [ˈdɔʏtʃ ɔɐdənsˌʃtaːt]) or Ordensstaat[3] ([ˈɔɐdənsˌʃtaːt]) in German, was a crusader state formed by the knights of the Teutonic Order during the 13th century Northern Crusades along the Baltic Sea. The state was based in Prussia after the Order's conquest of the Pagan Old Prussians. It expanded to include at various times Courland, Gotland, Livonia, Neumark, Pomerelia and Samogitia. Its territory was in the modern countries of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Germany, Poland, Russia and Sweden (Gotland). Most of the territory was conquered by military orders, after which German colonization occurred to varying effect.

State of the Teutonic Order | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1226–1525 | |||||||||||

Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||

The State of the Teutonic Order in 1410 | |||||||||||

| Status | State (1226-1525) Fief (Prussia only) of Poland[1] (1466–1525) | ||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||

| Common languages | Old Prussian language (Popular), Low German, Latin, Baltic languages, Estonian, Livonian, Polish | ||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic | ||||||||||

| Government | Theocratic military order | ||||||||||

| Grand Master | |||||||||||

• 1226–1239 | Hermann (first) | ||||||||||

• 1510–1525 | Albert (last) | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Estates[2] | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||

| March 1226 | |||||||||||

• Polish–Teutonic War | 1326–1332 | ||||||||||

| 15 July 1410 | |||||||||||

• Polish–Teutonic War | 1519–1521 | ||||||||||

| 8 April 1525 | |||||||||||

| 10 April 1525 | |||||||||||

| Currency | Mark | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Estonia Germany Latvia Lithuania Poland Russia | ||||||||||

The Livonian Brothers of the Sword controlling Terra Mariana were incorporated into the Teutonic Order as its autonomous branch Livonian Order in 1237.[4] In 1346, the Duchy of Estonia was sold by the King of Denmark for 19,000 Köln marks to the Teutonic Order. The shift of sovereignty from Denmark to the Teutonic Order took place on 1 November 1346.[5]

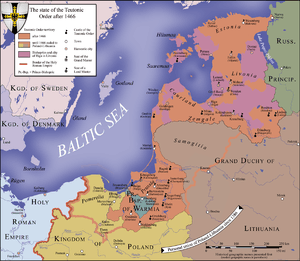

Following its defeat in the Battle of Grunwald in 1410 the Teutonic Order fell into decline and its Livonian branch joined the Livonian Confederation established in 1422–1435.[6] The Teutonic held lands in Prussia and Pomerania were split in two after the Peace of Thorn in 1466. The western part with was integrated with the Kingdom of Poland[7] as the province of Royal Prussia, the eastern part remained under Teutonic rule,[8] as a fief, also considered an integral part of the Kingdom of Poland.[1] The monastic state in the east was secularized in 1525 during the Protestant Reformation as the Duchy of Prussia, a Polish fief governed by the House of Hohenzollern. The Livonian branch continued as part of the Livonian Confederation until its dissolution in 1561.

Background

Poles in Old Prussia

The Old Prussians withstood many attempts at conquest preceding that of the Teutonic Knights. Bolesław I of Poland began the series of unsuccessful conquests when he sent Adalbert of Prague in 997. In 1147, Bolesław IV of Poland attacked Prussia with the aid of Kievan Rus, but was unable to conquer it. Numerous other attempts followed, and, under Duke Konrad I of Masovia, were intensified, with large battles and crusades in 1209, 1219, 1220 and 1222.[9]

History of Brandenburg and Prussia | ||||

| Northern March 965–983 |

Old Prussians pre-13th century | |||

| Lutician federation 983 – 12th century | ||||

| Margraviate of Brandenburg 1157–1618 (1806) (HRE) (Bohemia 1373–1415) |

Teutonic Order 1224–1525 (Polish fief 1466–1525) | |||

| Duchy of Prussia 1525–1618 (1701) (Polish fief 1525–1657) |

Royal (Polish) Prussia (Poland) 1454/1466 – 1772 | |||

| Brandenburg-Prussia 1618–1701 | ||||

| Kingdom in Prussia 1701–1772 | ||||

| Kingdom of Prussia 1772–1918 | ||||

| Free State of Prussia (Germany) 1918–1947 |

Klaipėda Region (Lithuania) 1920–1939 / 1945–present |

Recovered Territories (Poland) 1918/1945–present | ||

| Brandenburg (Germany) 1947–1952 / 1990–present |

Kaliningrad Oblast (Russia) 1945–present | |||

The West-Baltic Prussians successfully repelled most of the campaigns and managed to strike Konrad in retaliation. However, the Prussians and Yotvingians in the south had their territory conquered. The land of the Yotvingians was situated in the area of what is today the Podlaskie Voivodeship of Poland. The Prussians attempted to oust Polish or Masovian forces from Yotvingia and Culmerland (or Chełmno Land), which by now was partially conquered, devastated and almost totally depopulated.

Papal edicts

Konrad of Masovia had already called a crusade against the Old Prussians in 1208, but it was not successful. Konrad, acting on the advice of Christian, first bishop of Prussia, established the Order of Dobrzyń, a small group of 15 knights. The Order, however, was soon defeated and, in reaction, Konrad called on the Pope for yet another crusade and for help from the Teutonic Knights. As a result, several edicts called for crusades against the Old Prussians. The crusades, involving many of Europe's knights, lasted for sixty years.

In 1211, Andrew II of Hungary enfeoffed the Teutonic Knights with the Burzenland. In 1225, Andrew II expelled the Teutonic Knights from Transylvania, and they had to transfer to the Baltic Sea.

Early in 1224, Emperor Frederick II announced at Catania that Livonia, Prussia with Sambia, and a number of neighbouring provinces were under Imperial immediacy (German: Reichsfreiheit). This decree subordinated the provinces directly to the Roman Catholic Church and the Holy Roman Emperor as opposed to being under the jurisdiction of local rulers.

At the end of 1224, Pope Honorius III announced to all Christendom his appointment of Bishop William of Modena as the Papal Legate for Livonia, Prussia, and other countries.

As a result of the Golden Bull of Rimini in 1226 and the Papal Bull of Rieti of 1234, Prussia came into the Teutonic Order's possession. The Knights began the Prussian Crusade in 1230. Under their governance, woodlands were cleared and marshlands made arable, upon which many cities and villages were founded, including Marienburg (Malbork) and Königsberg (Kaliningrad).

Cities founded

Unlike newly founded cities between the rivers Elbe and Oder the cities founded by the Teutonic Order had a much more regular, rectangular sketch of streets, indicating their character as planned foundations.[10] The cities were heavily fortified, accounting for the long lasting conflicts with the resistive native Old Prussians, with armed forces under command of the knights.[10] Most cities were prevailingly populated with immigrants from Middle Germany and Silesia, where many knights of the order had their homelands.[11]

The cities were usually given Magdeburg law town privileges, with the one exception of Elbing (Elbląg), which was founded with the support of Lübeckers and thus was awarded Lübeck law.[10] While the Lübeckers provided the Order important logistic support with their ships, they were otherwise, with the exception of Elbing, rather uninvolved in the establishment of the Monastic State.[10]

History

13th century

In 1234, the Teutonic Order assimilated the remaining members of the Order of Dobrzyń and, in 1237, the Order of the Livonian Brothers of the Sword. The assimilation of the Livonian Brothers of the Sword (established in Livonia in 1202) increased the Teutonic Order's lands with the addition of the territories known today as Latvia and Estonia.

In 1243, the Papal legate William of Modena divided Prussia into four bishoprics: Culm (Chełmno), Pomesania, Ermland (Warmia) and Samland (Sambia). The bishoprics became suffragans to the Archbishopric of Riga under the mother city of Visby on Gotland. Each diocese was fiscally and administratively divided into one-third reserved for the maintenance of the capitular canons, and two-thirds were where the Order collected the dues. The cathedral capitular canons of Culm, Pomesania and Samland were simultaneously members of the Teutonic Order since the 1280s, ensuring a strong influence by the Order. Only Ermland's diocesan chapter maintained independence, enabling to establish its autonomous rule in the capitular third of Ermland's diocesan territory (Prince-Bishopric of Ermeland).

14th century

Danzig and the Hanse

At the beginning of the 14th century, the Duchy of Pomerania, a neighbouring region, plunged into war with Poland and the Margraviate of Brandenburg to the west. The Teutonic Knights seized the city of Danzig in November 1308. The Order had been called by King Władysław I of Poland. According to historical sources, many of the inhabitants of the city, Polish and German, were slaughtered. In September 1309, Margrave Waldemar of Brandenburg-Stendal sold his claim to the territory to the Teutonic Order for the sum of 10,000 Marks in the Treaty of Soldin. This marked the beginning of a series of conflicts between Poland and the Teutonic Knights as the Order continued incorporating territories into its domains.

While the Order promoted the Prussian cities by granting them extended surrounding territory and privileges, establishing courts, civil and commercial law, it allowed the cities less outward independence than free imperial cities enjoyed within the Holy Roman Empire.[11][12]

The members of the Hanseatic League did consider merchants from Prussian cities as their like, but also accepted the Grand Master[13] of the Order as the sole territorial ruler representing Prussia at their Hanseatic Diets.[10] Thus Prussian merchants, along with those from Ditmarsh, were the only beneficiaries of a quasi membership within the Hanse, although lacking the background of citizenship in a fully autonomous or free city.[14] Only merchants from the six Prussian Hanseatic cities of Braunsberg (Braniewo), Culm (Chełmno), Danzig, Elbing, Königsberg and Thorn (Toruń) were considered fully fledged members of the league, while merchants from other Prussian cities had a lesser status.[15]

The Teutonic Order's possession of Danzig was disputed by the Polish kings Władysław I and Casimir the Great—claims that led to the Polish–Teutonic War (1326–1332) and, eventually, lawsuits in the papal court in 1320 and 1333. A peace was concluded at Kalisz in 1343, where the Teutonic Order agreed that Poland should rule Pomerelia as a fief and Polish kings, therefore, retained the right to the title Duke of Pomerania. The title referred to the Duchy of Pomerelia. Unlike in English, German, Latin or Lithuanian language Polish uses the term Pomorze for Pomerania (since 1181 a fief within the Holy Roman Empire) and Pomerelia alike. Both duchies were earlier ruled by related dynasties, thus the semantic title was Duke of Pomerania rather than Duke of Pomerelia, as it was referred to in other languages.

Second Danish-Hanseatic War

In the conflict between the Hanse and Denmark on the trade in the Baltic King Valdemar IV of Denmark had held the Hanseatic city of Visby to ransom in 1361.[16] However, the members of the Hanseatic league were undecided to unite against him.[17] However, when Valdemar IV then captured Prussian merchant ships in the Øresund on their way to England, Grand Master Winrich of Kniprode travelled to Lübeck to propose a war alliance against Denmark, received with reluctance only by the important cities forming the Wendish-Saxon third of the Hanse.[18]

Since Valdemar IV had also attacked ships of the Dutch city of Kampen and other destinations in the Zuiderzee, Prussia and Dutch cities, such as Kampen, Elburg and Harderwijk, allied themselves against Denmark.[18] This then made the Hanse calling up a diet in Cologne in 1367, also convening the afore-mentioned and more non-member cities like Amsterdam and Brielle, founding the Cologne Federation as a war alliance, in order to ban the Danish threat.[19] More cities from the Lower Rhine area till up to Livonia joined.[19]

Of the major players only Bremen and Hamburg refused to send forces, but contributed financially.[20] Besides Prussia, three more territorial partners, Henry II of Schauenburg and Holstein-Rendsburg, Albert II of Mecklenburg, and the latter's son Albert of Sweden, joined the alliance, attacking via land and sea, forcing Denmark to sign the Treaty of Stralsund in 1370.[20] Several Danish castles and fortresses were then taken by Hanse forces for fifteen years, in order to secure the implementation of the peace conditions.

English Merchant Adventurers

The invasions of the Teutonic Order from Livonia to Pleskau in 1367 had caused the Russians to recoup themselves on Hanse merchants in Novgorod, which again made the Order block exports of salt and herring into Russia.[21] While the relations had eased by 1371 so that trade resumed, they soured again until 1388.[22]

During the Lithuanian crusade of 1369/1370, ending with the Teutonic victory in the Battle of Rudau, Prussia enjoyed considerable support from English knights.[23] The Order welcomed English Merchant Adventurers, starting to cruise in the Baltic, competing with Dutch, Saxon and Wendish Hanseatic merchants, and allowed them to open outposts in its cities of Danzig and Elbing.[24] This necessarily brought about a conflict with the rest of the Hanse, which was in a heavy argument with Richard II of England, over levies of higher dues. The Merchants struggled to achieve an unsatisfactory compromise.[23]

Dissatisfied Richard II's navy suddenly attacked six Prussian ships in May 1385 – and those of more Hanse members – in the Zwin,[25] Grand Master Conrad Zöllner von Rothenstein immediately terminated all trade with England.[25] When in the same year the Hanse evacuated all their Danish castles in fulfillment of the Treaty of Stralsund, Prussia argued in favour of a renewal of the Cologne Federation for the deeply concerned about the ensuing conflict with England, but could not prevail.[26]

The cities preferred to negotiate and take retaliatory actions, such as counter-confiscation of English merchandise.[25] So when in 1388 Richard II finally reconfirmed the Hanseatic trade privileges, Prussia once again permitted merchant adventurers, granting permissions to remain; for this action they were renounced once again by the Grand Master Conrad of Jungingen in 1398.[25]

In the conflict with the Burgundian Philip the Bold on the Hanse privileges in the Flemish cities the positions of the Hanse cities and Prussia were again reversed. Here the majority of the Hanse members decided in the Hanseatic Diet on 1 May 1388 for an embargo against the Flemish cities. Meanwhile, Prussia could not prevail with its plea for further negotiations.[27]

Trading

The Order's Großschäffer was one of the leading functionaries of the order. The word translates about as "chief sales and buying officer" with procuration. They were in charge of the considerable commerce, import, export, crediting, real estate investment etc., which the Order carried out, using its network of bailiwicks and agencies spanned over much of Central, Western and Southern Europe and the Holy Land. The other Großschäffer in Marienburg had the grain export monopoly. As to imports both were not bound to any particular merchandise. From Königsberg, holding the monopoly in amber export, achieved the exceptional permission to continue amber exports to Flanders and textile imports in return.[28] On the occasion of the ban on Flemish trade, the Hanse urged Prussia and Livonia again to interrupt the exchange with Novgorod as well, but with both blockades Russian and Flemish commodities could not reach their final destinations.[22] In 1392 it was then Grand Master Conrad of Wallenrode who supported the Flemish to achieve an acceptable agreement with the Hanse resuming the bilateral trade.[28] While a Hanseatic delegation under Johann Niebur reopened trade with Novgorod in the same year, after reconfirmation of the previous mutual privileges.[22]

Since the late 1380s grave piracy by privateers, promoted by Albert of Sweden and Mecklenburg actually directed against Margaret I of Denmark, blocked seafaring to the herring supplies at the Scania Market, thus fish prices tripled in Prussia.[29] The Saxon Hanse cities urged Prussia to intervene, but Conrad of Jungingen was more worried about a Danish victory.[29] So only after the cities, led by Lübeck's burgomaster Hinrich Westhof, had liaised the Treaty of Skanör (1395), Albert's defeat manifested, so that Prussia finally sent out its ships, led by Danzig's city councillor Conrad Letzkau.[30][31] Until 1400 the united Teutonic-Hanseatic flotilla then thoroughly cleared the Baltic Sea from pirates, the Victual Brothers, and even took the island of Gotland in 1398.[30][31]

| Saffron | 7040 | Hungarian Iron | 21 |

| Ginger | 1040 | Trave Salt | 12.5 |

| Pepper | 640 | Herring | 12 |

| Wax | 237.5 | Flemish salt | 8 |

| French wine | 109.5 | Wismar beer | 7.5 |

| Rice | 80 | Flour | 7.5 |

| Steel | 75 | Wheat | 7 |

| Rhenish wine | 66 | Rye | 5.75 |

| Oil | 60 | Barley | 4.2 |

| Honey | 35 | Ash woad | 4.75 |

| Butter | 30 |

15th century

Konrad von Jungingen

At the beginning of the 15th century, the State of the Teutonic Order stood at the height of its power under Konrad (Conrad) von Jungingen. The Teutonic navy ruled the Baltic Sea from bases in Prussia and Gotland, and the Prussian cities provided tax revenues sufficient to maintain a significant standing force composed of Teutonic Knights proper, their retinues, Prussian peasant levies, and German mercenaries.

In 1402, the March of Brandenburg gave the New March (Neumark) in pawn to the Teutonic Order, which kept it until Brandenburg redeemed it again in 1454 and 1455, respectively, by the Treaties of Cölln and Mewe. Though the possession of this territory by the Order strengthened ties between the Order and their secular counterparts in northern Germany, it exacerbated the already hostile relationship between the Order and Polish–Lithuanian union.

In March 1407, Konrad died from complications caused by gallstones and was succeeded by his younger brother, Ulrich von Jungingen. Under Ulrich, the Teutonic State fell from its precarious height and became mired in internal political strife, near-constant war with Polish–Lithuanian union, and crippling war debts.

Losses to Poland, Polish suzerainty

In 1408, Conrad Letzkau served as a diplomat to Queen Margaret I and arranged that the Order sell Gotland to Denmark.[30] In 1410, with the death of Rupert, King of the Germans, war broke out between the Teutonic Knights, supported by Pomerania, and a Polish-Lithuanian alliance supported by Ruthenian and Tatar auxiliary forces. Poland and Lithuania triumphed following a victory at the Battle of Grunwald (Tannenberg).

The Order assigned Heinrich von Plauen to defend Prussian Pomerania (Pomerelia), who moved rapidly to bolster the defence of Marienburg Castle in Prussian Pomesania. Heinrich von Plauen was elected vice-grand master and led the Teutonic Knights through the Siege of Marienburg in 1410. Eventually von Plauen was promoted to Grand Master and, in 1411, concluded the First Treaty of Thorn with King Władysław II Jagiełło of Poland.

In March 1440, gentry (mainly from Culmerland) and the Hanseatic cities of Danzig, Elbing, Kneiphof, Thorn and other Prussian cities founded the Prussian Confederation to free themselves from the overlordship of the Teutonic Knights. Due to the heavy losses and costs after the war against Poland and Lithuania, the Teutonic Order collected taxes at steep rates. Furthermore, the cities were not allowed due representation by the Teutonic Order.

In February 1454, the Prussian Confederation asked King Casimir IV of Poland to support their revolt and to incorporate the region to the Kingdom of Poland. King Casimir IV agreed and signed the act of incorporation in Kraków on 6 March 1454.[33] The Thirteen Years' War, the longest of the Polish–Teutonic wars, (also known as the War of the Cities) broke out. Various cities of the region pledged allegiance to the Polish King in 1454.[34]

The Second Peace of Thorn in October 1466 ended the war and provided for the Teutonic Order's cession of its rights over the western half of its territories to the Polish Kingdom,[7] which became the Polish province of Royal Prussia and the remaining part of the Order's land became a fief and protectorate of Poland, considered part of one and indivisible Kingdom of Poland.[1] In accordance to the peace treaty, from now on, every Grand Master was obliged to swear an oath of allegiance to the reigning Polish king within six months of taking office, and any new territorial acquisitions by the Teutonic Order, also outside Prussia, would also be incorporated into Poland.[35] The Grand Master of the Teutonic Order became a prince and counselor of the Polish king and the Kingdom of Poland.[36]

Formation of a new nobility

While the Knights of the Teutonic Order formed a thin ruling class by themselves, they have extensively used mercenaries, mostly German, from the Holy Roman Empire, to whom they granted lands in return. This gradually created a new class of landed nobility. Due to several factors, among which was the high rate of early death in battle, these lands became concentrated over time in the hands of a relatively small number of noblemen each having a vast estate. This nobility would evolve to what is known as the Prussian Junker nobility.[37]

16th century and aftermath

Transformation to Ducal Prussia

During the Protestant Reformation, endemic religious upheavals and wars occurred across the region. In 1525, during the aftermath of the Polish-Teutonic War (1519–1521), Sigismund I the Old, King of Poland, and his nephew, the last Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights, Albert of Brandenburg-Ansbach, a member of a cadet branch of the House of Hohenzollern, agreed that the latter would resign his position, adopt Lutheran faith and assume the title of Duke of Prussia. Thereafter referred to as Ducal Prussia (German: Herzogliches Preußen, Preußen Herzoglichen Anteils; Polish: Prusy Książęce), remaining a Polish fief.

Thus in a deal partially brokered by Martin Luther, Roman Catholic Teutonic Prussia was transformed into the Duchy of Prussia, the first Protestant state. Sigismund's consent was bound to Albert's submission to Poland, which became known as the Prussian Homage. On 10 December 1525 at their session in Königsberg the Prussian estates established the Lutheran Church in Ducal Prussia by deciding the Church Order.[38]

The Habsburg-led Holy Roman Empire continued to hold its claim to Prussia and furnished grand masters of the Teutonic Order, who were merely titular administrators of Prussia, but managed to retain many of the Teutonic holdings elsewhere outside of Prussia. Joachim II Hector, Elector of Brandenburg, who had converted to Lutheranism in 1539, was after the co-enfeoffment of his line of the Hohenzollern with the Prussian dukedom. So he tried for gaining his brother-in-law Sigismund II Augustus of Poland and finally succeeded, including the then usual expenses. On 19 July 1569, when Albert Frederick rendered King Sigismund II homage and was in return enfeoffed as Duke of Prussia in Lublin, the King simultaneously enfeoffed Joachim II and his descendants as co-heirs.

Personal union with Brandenburg

In 1618, the Prussian Hohenzollern were extinct in the male line, and so the Polish fief of Prussia was passed on to the senior Brandenburg Hohenzollern line, the ruling margraves and prince-electors of Brandenburg, who thereafter ruled Brandenburg (a fief of the Holy Roman Empire), and Ducal Prussia (a Polish fief), in personal union. This legal contradiction made a cross-border real union impossible; however, in practice, Brandenburg and Ducal Prussia were more and more ruled as one, and colloquially referred to as Brandenburg-Prussia.

Frederick William, Duke of Prussia and Prince-elector of Brandenburg, sought to acquire Royal Prussia in order to territorially connect his two existing fiefs. An opportunity occurred when Charles X Gustav of Sweden, in his attempt to conquer Poland (cf. Swedish Deluge), promised to cede to Frederick William the Polish-Prussian voivodeships of Chełmno, Malbork and Pomerania (Pomerelia) as well as the Prince-Bishopric of Ermeland, if Frederick William supported the Swedish campaign. This offer was speculative since Frederick William would have to commit to military support of the campaign, while the reward was conditional on achieving victory.

John II Casimir of Poland forestalled the Swedish-Prussian alliance by submitting a counter-offer, which Frederick William accepted. On 29 July 1657 they signed the Treaty of Wehlau in Wehlau (Polish: Welawa; today Znamensk). In return for Frederick William's renunciation of the Swedish-Prussian alliance, John Casimir recognised Frederick William's full sovereignty over the Duchy of Prussia (German: Herzogtum Preußen). Thus after more than 130 years of Polish suzerainty, Prussia regained full sovereignty in 1657 (definitively confirmed by the Peace of Oliva in 1660), a necessary prerequisite for elevating Ducal Prussia to become the sovereign Kingdom of Prussia in 1701 (not to be confused with Polish Royal Prussia).

The nature of the de facto collectively ruled governance of Brandenburg-Prussia became more apparent through the titles of the higher ranks of the Prussian government, seated in Brandenburg's capital of Berlin after the return of the court from Königsberg, where they had sought refuge from the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648). However, the legal amalgamation of the Kingdom of Prussia (a sovereign state) with Brandenburg (a fief of the Holy Roman Empire) was achieved only after the dissolution of the Empire in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

Archaeology

Fortifications of the Ordensstaat have been examined through archaeological excavation since the end of World War II, especially those built or expanded during the fourteenth century. Fortifications are generally the best preserved material legacy of the Order's presence in the Baltic today, and timber and earth, as well as brick examples, are attested in the archaeological record. The earliest castles in the Ordensstaat consisted of simple buildings attached to a fortified enclosure and, whilst the quadrangular red-brick structure would come to typify convent buildings, single-wing castles would continue to be built alongside timber towers.[39] Where they followed the conventional layout, castles included a connected set of communal spaces such as a dormitory, refectory, kitchen, chapter house, a chapel or church, an infirmary, and tower projecting over the moat.

Marienburg fort

Construction began on Marienburg during the third quarter of the thirteenth century, and work continued on it until the middle of the fifteenth century. A settlement developed alongside the castle, which together enclosed 25 hectares. Granted town rights in 1286, its castle is larger than any other built by the Order. Since 1997 the outer bailey has been thoroughly excavated, dating to the mid-1350s. Preserved at Marienburg was a polychrome statue of Mary about eight meters in height, made of artificial stone and originally decorated with mosaic tiles. Mary was the most important patron of the knights and central to the liturgy of the Teutonic Order, so it is not surprising to find such striking representations of her at their most prominent castle.

Coins

Coins were minted from the late 1250s. These were often simple in design, stamped with the cross of the Order on one side, but support the notion that crusading, colonisation, and a supporting infrastructure went hand in hand from the earliest years of the Prussian Crusade.[40]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to State of the Teutonic Order. |

Notes

- Górski 1949, p. 96-97, 214-215.

- Stone, Daniel (2001). A History of Central Europe. University of Washington Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 0-295-98093-1.

- France, John (2005). The Crusades and the Expansion of Catholic Christendom, 1000–1714. New York: Routledge. p. 380. ISBN 0-415-37128-7.

- Frucht, Richard C. (2005). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 69. ISBN 1-57607-800-0.

- Skyum-Nielsen, Niels (1981). Danish Medieval History & Saxo Grammaticus. Museum Tusculanum Press. p. 129. ISBN 87-88073-30-0.

- Housley, Norman (1992). The later Crusades, 1274–1580. p. 371. ISBN 0-19-822136-3.

- Górski 1949, p. 88-92, 206-210.

- Górski 1949, p. 93-94, 212.

- Lewinski Corwin, Edward Henry (1917). The Political History of Poland. The Polish Book Importing Company. p. 45.

lizard union.

- Philippe Dollinger, Die Hanse [La Hanse (XIIe-XVIIe siècles); German], see references for bibliographical details, p. 55. ISBN 3-520-37105-7.

- Philippe Dollinger, Die Hanse [La Hanse (XIIe-XVIIe siècles); German], see references for bibliographical details, p. 54. ISBN 3-520-37105-7.

- Philippe Dollinger, Die Hanse [La Hanse (XIIe-XVIIe siècles); German], see references for bibliographical details, p. 123. ISBN 3-520-37105-7.

- in German: Hochmeister, literally "High Master".

- Philippe Dollinger, Die Hanse [La Hanse (XIIe-XVIIe siècles); German], see references for bibliographical details, p. 124. ISBN 3-520-37105-7.

- Cf. Philippe Dollinger, Die Hanse [La Hanse (XIIe-XVIIe siècles); German], see references for bibliographical details, p. 123. ISBN 3-520-37105-7.

- Philippe Dollinger, Die Hanse [La Hanse (XIIe-XVIIe siècles); German], see references for bibliographical details, p. 96. ISBN 3-520-37105-7.

- Philippe Dollinger, Die Hanse [La Hanse (XIIe-XVIIe siècles); German], see references for bibliographical details, p. 97. ISBN 3-520-37105-7.

- Philippe Dollinger, Die Hanse [La Hanse (XIIe-XVIIe siècles); German], see references for bibliographical details, p. 98. ISBN 3-520-37105-7.

- Philippe Dollinger, Die Hanse [La Hanse (XIIe-XVIIe siècles); German], see references for bibliographical details, p. 99. ISBN 3-520-37105-7.

- Philippe Dollinger, Die Hanse [La Hanse (XIIe-XVIIe siècles); German], see references for bibliographical details, p. 100. ISBN 3-520-37105-7.

- Philippe Dollinger, Die Hanse [La Hanse (XIIe-XVIIe siècles); German], see references for bibliographical details, pp. 109seq. ISBN 3-520-37105-7.

- Philippe Dollinger, Die Hanse [La Hanse (XIIe-XVIIe siècles); German], see references for bibliographical details, p. 110. ISBN 3-520-37105-7.

- Philippe Dollinger, Die Hanse [La Hanse (XIIe-XVIIe siècles); German], see references for bibliographical details, p. 104. ISBN 3-520-37105-7.

- Philippe Dollinger, Die Hanse [La Hanse (XIIe-XVIIe siècles); German], see references for bibliographical details, pp. 103seq. ISBN 3-520-37105-7.

- Philippe Dollinger, Die Hanse [La Hanse (XIIe-XVIIe siècles); German], see references for bibliographical details, p. 105. ISBN 3-520-37105-7.

- Philippe Dollinger, Die Hanse [La Hanse (XIIe-XVIIe siècles); German], see references for bibliographical details, p. 102. ISBN 3-520-37105-7.

- Philippe Dollinger, Die Hanse [La Hanse (XIIe-XVIIe siècles); German], see references for bibliographical details, p.107. ISBN 3-520-37105-7.

- Philippe Dollinger, Die Hanse [La Hanse (XIIe-XVIIe siècles); German], see references for bibliographical details, p. 108. ISBN 3-520-37105-7.

- Philippe Dollinger, Die Hanse [La Hanse (XIIe-XVIIe siècles); German], see references for bibliographical details, p. 113. ISBN 3-520-37105-7.

- Natalia Borzestowska and Waldemar Borzestowski, "Dlaczego zginął burmistrz", 17 October 2005, retrieved on 8 September 2011.

- Philippe Dollinger, Die Hanse [La Hanse (XIIe-XVIIe siècles); German], see references for bibliographical details, p. 114. ISBN 3-520-37105-7.

- W.Bonhke, Der Binnenhandel des Deutschen Ordens in Preusen, in Hansische Geschichtsblatter, 80 (1962), pp.51–3

- Górski 1949, p. 54.

- Górski 1949, p. 71-72, 76, 79.

- Górski 1949, p. 96-97, 215.

- Górski 1949, p. 96, 103, 214, 221.

- Rosenberg, H. (1943). The Rise of the Junkers in Brandenburg-Prussia, 1410-1653: Part 1. The American Historical Review, 49(1), 1-22.

- Albertas Juška, Mažosios Lietuvos Bažnyčia XVI-XX amžiuje, Klaipėda: 1997, pp. 742–771, here after the German translation Die Kirche in Klein Litauen (section: 2. Reformatorische Anfänge; (in German)) on: Lietuvos Evangelikų Liuteronų Bažnyčia, retrieved on 28 August 2011.

- Pluskowski, Aleksander (2013). The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade: Holy War and Colonization. Routledge. p. 149.

- Pluskowski, Aleksander (2013). The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade: Holy War and Colonization. Routledge. p. 110.

References

- Dollinger, Philippe (1998) [1966]. Hans Krabusch and Marga Krabusch (trls.) (ed.). Die Hanse (La Hanse (XIIe-XVIIe siècles, Paris, Aubier, 1964) (in German). 371. Stuttgart: Kröner: Kröners Taschenbuchausgabe. ISBN 3-520-37105-7.

- Pluskowski, Aleksander. The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade: Holy War and Colonization. London: Routledge, 2013. ISBN 0415691710

- Górski, Karol (1949). Związek Pruski i poddanie się Prus Polsce: zbiór tekstów źródłowych (in Polish and Latin). Poznań: Instytut Zachodni.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Ordensland.de: cities, castles and landscapes of the Teutonic Knights (in German)

- Teutonic Order (at worldstatesmen)