Son of God

Historically, many rulers have assumed titles such as son of God, son of a god or son of heaven.[1]

The term "son of God" is used in the Hebrew Bible as another way of referring to humans with special relationships with God. In Exodus, the nation of Israel is called God's "Firstborn son".[2] In Psalms, David is called "son of God", even commanded to proclaim that he is God's "begotten son" on the day he was made king.[3][4] Solomon is also called "son of God".[5][6] Angels, just and pious men, and the kings of Israel are all called "sons of God."[7]

In the New Testament of the Christian Bible, "Son of God" is applied to Jesus on many occasions.[7] Jesus is declared to be the Son of God on two separate occasions by a voice speaking from Heaven. Jesus is explicitly and implicitly described as the Son of God by himself and by various individuals who appear in the New Testament.[7][8][9][10][7] Jesus is called "son of God," while followers of Jesus are called, "sons of God".[11] As applied to Jesus, the term is a reference to his role as the Messiah, the King chosen by God.[12] The contexts and ways in which Jesus' title, Son of God, means something more than or other than Messiah remain the subject of ongoing scholarly study and discussion.

The term "Son of God" should not be confused with the term "God the Son" (Greek: Θεός ὁ υἱός), the second Person of the Trinity in Christian theology. The doctrine of the Trinity identifies Jesus as God the Son, identical in essence but distinct in person with regard to God the Father and God the Holy Spirit (the first and third Persons of the Trinity). Nontrinitarian Christians accept the application to Jesus of the term "Son of God", which is found in the New Testament.

Rulers and imperial titles

Throughout history, emperors and rulers ranging from the Western Zhou dynasty (c. 1000 BC) in China to Alexander the Great (c. 360 BC) to the Emperor of Japan (c. 600 AD) have assumed titles that reflect a filial relationship with deities.[1][13][14][15]

The title "Son of Heaven" i.e. 天子 (from 天 meaning sky/heaven/god and 子 meaning child) was first used in the Western Zhou dynasty (c. 1000 BC). It is mentioned in the Shijing book of songs, and reflected the Zhou belief that as Son of Heaven (and as its delegate) the Emperor of China was responsible for the well being of the whole world by the Mandate of Heaven.[13][14] This title may also be translated as "son of God" given that the word Ten or Tien in Chinese may either mean sky or god.[16] The Emperor of Japan was also called the Son of Heaven (天子 tenshi) starting in the early 7th century.[17]

Among the Eurasian nomads, there was also a widespread use of "Son of God/Son of Heaven" for instance, in the third century BC, the ruler was called Chanyü[18] and similar titles were used as late as the 13th century by Genghis Khan.[19]

Examples of kings being considered the son of god are found throughout the Ancient Near East. Egypt in particular developed a long lasting tradition. Egyptian pharaohs are known to have been referred to as the son of a particular god and their begetting in some cases is even given in sexually explicit detail. Egyptian pharaohs did not have full parity with their divine fathers but rather were subordinate.[20]:36 Nevertheless, in the first four dynasties, the pharaoh was considered to be the embodiment of a god. Thus, Egypt was ruled by direct theocracy,[21] wherein "God himself is recognized as the head" of the state.[22] During the later Amarna Period, Akhenaten reduced the Pharaoh's role to one of coregent, where the Pharaoh and God ruled as father and son. Akhenaten also took on the role of the priest of god, eliminating representation on his behalf by others. Later still, the closest Egypt came to the Jewish variant of theocracy was during the reign of Herihor. He took on the role of ruler not as a god but rather as a high-priest and king.[21]

Jewish kings are also known to have been referred to as "son of the LORD".[23]:150 The Jewish variant of theocracy can be thought of as a representative theocracy where the king is viewed as God's surrogate on earth.[21] Jewish kings thus, had less of a direct connection to god than pharaohs. Unlike pharaohs, Jewish kings rarely acted as priests, nor were prayers addressed directly to them. Rather, prayers concerning the king are addressed directly to god.[20]:36–38 The Jewish philosopher Philo is known to have likened God to a supreme king, rather than likening Jewish kings to gods.[24]

Based on the Bible, several kings of Damascus took the title son of Hadad. From the archaeological record a stela erected by Bar-Rakib for his father Panammuwa II contains similar language. The son of Panammuwa II a king of Sam'al referred to himself as a son of Rakib.[20]:26–27 Rakib-El is a god who appears in Phoenician and Aramaic inscriptions.[25] Panammuwa II died unexpectedly while in Damascus.[26] However, his son the king Bar-Rakib was not a native of Damascus but rather the ruler of Sam'al it is unknown if other rules of Sam'al used similar language.

In Greek mythology, Heracles (son of Zeus) and many other figures were considered to be sons of gods through union with mortal women. From around 360 BC onwards Alexander the Great may have implied he was a demigod by using the title "Son of Ammon–Zeus".[27]

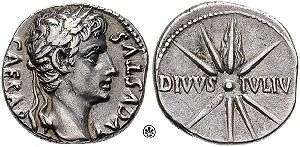

In 42 BC, Julius Caesar was formally deified as "the divine Julius" (divus Iulius) after his assassination. His adopted son, Octavian (better known as Augustus, a title given to him 15 years later, in 27 BC) thus became known as divi Iuli filius (son of the divine Julius) or simply divi filius (son of the god).[28] As a daring and unprecedented move, Augustus used this title to advance his political position in the Second Triumvirate, finally overcoming all rivals for power within the Roman state.[28][29]

The word applied to Julius Caesar as deified was divus, not the distinct word deus. Thus Augustus called himself Divi filius, and not Dei filius.[30] The line between been god and god-like was at times less than clear to the population at large, and Augustus seems to have been aware of the necessity of keeping the ambiguity.[30] As a purely semantic mechanism, and to maintain ambiguity, the court of Augustus sustained the concept that any worship given to an emperor was paid to the "position of emperor" rather than the person of the emperor.[31] However, the subtle semantic distinction was lost outside Rome, where Augustus began to be worshiped as a deity.[32] The inscription DF thus came to be used for Augustus, at times unclear which meaning was intended.[30][32] The assumption of the title Divi filius by Augustus meshed with a larger campaign by him to exercise the power of his image. Official portraits of Augustus made even towards the end of his life continued to portray him as a handsome youth, implying that miraculously, he never aged. Given that few people had ever seen the emperor, these images sent a distinct message.[33]

Later, Tiberius (emperor from 14–37 AD) came to be accepted as the son of divus Augustus and Hadrian as the son of divus Trajan.[28] By the end of the 1st century, the emperor Domitian was being called dominus et deus (i.e. master and god).[34]

Outside the Roman Empire, the 2nd-century Kushan King Kanishka I used the title devaputra meaning "son of God".[35]

Bahá'í Faith

In the writings of the Bahá'í Faith, the term "Son of God" is applied to Jesus,[36] but does not indicate a literal physical relationship between Jesus and God,[37] but is symbolic and is used to indicate the very strong spiritual relationship between Jesus and God[36] and the source of his authority.[37] Shoghi Effendi, the head of the Bahá'í Faith in the first half of the 20th century, also noted that the term does not indicate that the station of Jesus is superior to other prophets and messengers that Bahá'ís name Manifestations of God, including Buddha, Muhammad and Baha'u'llah among others.[38] Shoghi Effendi notes that, since all Manifestations of God share the same intimate relationship with God and reflect the same light, the term Sonship can in a sense be attributable to all the Manifestations.[36]

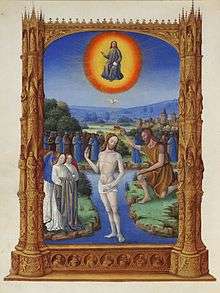

Christianity

In Christianity, the title "Son of God" refers to the status of Jesus as the divine son of God the Father.[39][40] It derives from several uses in the New Testament and early Christian theology.

Islam

In Islam, Jesus is known as Īsā ibn Maryam (Arabic: عيسى بن مريم, lit. 'Jesus, son of Mary'), and is understood to be a prophet and messenger of God (Allah) and al-Masih, the Arabic term for Messiah (Christ), sent to guide the Children of Israel (banī isrā'īl in Arabic) with a new revelation, the al-Injīl (Arabic for "the gospel").[41][42][43]

Islam rejects any kinship between God and any other being, including a son.[44][45] Thus, rejecting the belief that Jesus is the begotten son of God (Allah), God (Allah) himself[46] or another god.[47] As in Christianity, Islam believes Jesus had no earthly father. In Islam Jesus is believed to be born due to the command of God (Allah) "be".[48] God (Allah) ordered[44] the angel Jibrīl (Gabriel) to "blow"[49] the soul of Jesus into Mary[50][51] and so she gave birth to Jesus. Islamic scholars debate whether or not, the title Son of God might apply to Jesus in an adoptive rather than generative sense, just like Abraham was taken as a friend of God.[52]

Judaism

Although references to "sons of God", "son of God" and "son of the LORD" are occasionally found in Jewish literature, they never refer to physical descent from God.[53][54] There are two instances where Jewish kings are figuratively referred to as a god.[23]:150 The king is likened to the supreme king God.[24] These terms are often used in the general sense in which the Jewish people were referred to as "children of the LORD your God".[53]

When used by the rabbis, the term referred to Israel or to human beings in general, and not as a reference to the Jewish mashiach.[53] In Judaism the term mashiach has a broader meaning and usage and can refer to a wide range of people and objects, not necessarily related to the Jewish eschaton.

Gabriel's Revelation

Gabriel's Revelation, also called the Vision of Gabriel[55] or the Jeselsohn Stone,[56] is a three-foot-tall (one metre) stone tablet with 87 lines of Hebrew text written in ink, containing a collection of short prophecies written in the first person and dated to the late 1st century BC.[57][58] It is a tablet described as a "Dead Sea scroll in stone".[57][59]

The text seems to talk about a messianic figure from Ephraim who broke evil before righteousness by three days.[60]:43–44 Later the text talks about a “prince of princes" a leader of Israel who was killed by the evil king and not properly buried.[60]:44 The evil king was then miraculously defeated.[60]:45 The text seems to refer to Jeremiah Chapter 31.[60]:43 The choice of Ephraim as the lineage of the messianic figure described in the text seems to draw on passages in Jeremiah, Zechariah and Hosea. This leader was referred to as a son of God.[60]:43–44, 48–49

The text seems to be based on a Jewish revolt recorded by Josephus dating from 4 BC.[60]:45–46 Based on its dating the text seems to refer to Simon of Peraea, one of the three leaders of this revolt.[60]:47

Dead Sea Scrolls

In some versions of Deuteronomy the Dead Sea Scrolls refer to the sons of God rather than the sons of Israel, probably in reference to angels. The Septuagint reads similarly.[23]:147[61]

4Q174 is a midrashic text in which God refers to the Davidic messiah as his son.[62]

4Q246 refers to a figure who will be called the son of God and son of the Most High. It is debated if this figure represents the royal messiah, a future evil gentile king or something else.[62][63]

In 11Q13 Melchizedek is referred to as god the divine judge. Melchizedek in the bible was the king of Salem. At least some in the Qumran community seemed to think that at the end of days Melchizedek would reign as their king.[64] The passage is based on Psalm 82.[65]

Pseudepigrapha

In both Joseph and Aseneth and the related text The Story of Asenath, Joseph is referred to as the son of God.[23]:158–159[66] In the Prayer of Joseph both Jacob and the angel are referred to as angels and the sons of God.[23]:157

References

- Introduction to the Science of Religion by Friedrich Muller 2004 ISBN 1-4179-7401-X page 136

- The Tanach - The Torah/Prophets/Writings. Stone Edition. 1996. p. 143. ISBN 0-89906-269-5.

- The Tanach - The Torah/Prophets/Writings. Stone Edition. 1996. p. 1439. ISBN 0-89906-269-5.

- The Tanach - The Torah/Prophets/Writings. Stone Edition. 1996. p. 1515. ISBN 0-89906-269-5.

- The Tanach - The Torah/Prophets/Writings. Stone Edition. 1996. p. 741. ISBN 0-89906-269-5.

- The Tanach - The Torah/Prophets/Writings. Stone Edition. 1996. p. 1923. ISBN 0-89906-269-5.

- "Catholic Encyclopedia: Son of God". Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- One teacher: Jesus' teaching role in Matthew's gospel by John Yueh-Han Yieh 2004 ISBN 3-11-018151-7 pages 240–241

- Dwight Pentecost The words and works of Jesus Christ 2000 ISBN 0-310-30940-9 page 234

- The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia by Geoffrey W. Bromiley 1988 ISBN 0-8028-3785-9 pages 571–572

- "International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: Sons of God (New Testament)". BibleStudyTools.com. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- Merriam-Webster's collegiate dictionary (10th ed.). (2001). Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster.

- China : a cultural and historical dictionary by Michael Dillon 1998 ISBN 0-7007-0439-6 page 293

- East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History by Patricia Ebrey, Anne Walthall, James Palais 2008 ISBN 0-547-00534-2 page 16

- A History of Japan by Hisho Saito 2010 ISBN 0-415-58538-4 page

- The Problem of China by Bertrand Russell 2007 ISBN 1-60520-020-4 page 23

- Boscaro, Adriana; Gatti, Franco; Raveri, Massimo, eds. (2003). Rethinking Japan: Social Sciences, Ideology and Thought. II. Japan Library Limited. p. 300. ISBN 0-904404-79-X.

- Britannica, Encyclopaedia. "Xiongnu". Xiongnu (people) article. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- Darian Peters (July 3, 2009). "The Life and Conquests of Genghis Khan". Humanities 360. Archived from the original on April 26, 2014.

- Adela Yarbro Collins, John Joseph Collins (2008). King and Messiah as Son of God: Divine, Human, and Angelic Messianic Figures in Biblical and Related Literature. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. Retrieved 3 February 2014.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Jan Assmann (2003). The Mind of Egypt: History and Meaning in the Time of the Pharaohs. Harvard University Press. pp. 300–301. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- "Catholic Encyclopedia". Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- Riemer Roukema (2010). Jesus, Gnosis and Dogma. T&T Clark International. Retrieved 30 January 2014.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Jonathan Bardill (2011). Constantine, Divine Emperor of the Christian Golden Age. Cambridge University Press. p. 342. Retrieved 4 February 2014.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- K. van der Toorn; Bob Becking; Pieter Willem van der Horst, eds. (1999). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible DDD. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 686. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- K. Lawson Younger, Jr. "Panammuwa and Bar-Rakib: two structural analyses" (PDF). University of Sheffield. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2014.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Cartledge, Paul (2004). "Alexander the Great". History Today. 54: 1.

- Early Christian literature by Helen Rhee 2005 ISBN 0-415-35488-9 pages 159–161

- Augustus by Pat Southern 1998 ISBN 0-415-16631-4 page 60

- The world that shaped the New Testament by Calvin J. Roetzel 2002 ISBN 0-664-22415-6 page 73

- Experiencing Rome: culture, identity and power in the Roman Empire by Janet Huskinson 1999 ISBN 978-0-415-21284-7 page 81

- A companion to Roman religion edited by Jörg Rüpke 2007 ISBN 1-4051-2943-3 page 80

- Gardner's art through the ages: the western perspective by Fred S. Kleiner 2008 ISBN 0-495-57355-8 page 175

- The Emperor Domitian by Brian W. Jones 1992 ISBN 0-415-04229-1 page 108

- Encyclopedia of ancient Asian civilizations by Charles Higham 2004 ISBN 978-0-8160-4640-9 page 352

- Lepard, Brian D (2008). In The Glory of the Father: The Baha'i Faith and Christianity. Bahá'í Publishing Trust. pp. 74–75. ISBN 1-931847-34-7.

- Taherzadeh, Adib (1977). The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh, Volume 2: Adrianople 1863–68. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. p. 182. ISBN 0-85398-071-3.

- Hornby, Helen, ed. (1983). Lights of Guidance: A Bahá'í Reference File. New Delhi, India: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. p. 491. ISBN 81-85091-46-3.

- J. Gordon Melton, Martin Baumann, Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, ABC-CLIO, USA, 2010, p. 634-635

- Schubert M. Ogden, The Understanding of Christian Faith, Wipf and Stock Publishers, USA, 2010, p. 74

- Glassé, Cyril (2001). The new encyclopedia of Islam, with introduction by Huston Smith (Édition révisée. ed.). Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press. p. 239. ISBN 9780759101906.

- McDowell, Jim, Josh; Walker, Jim (2002). Understanding Islam and Christianity: Beliefs That Separate Us and How to Talk About Them. Euguen, Oregon: Harvest House Publishers. p. 12. ISBN 9780736949910.

- The Oxford Dictionary of Islam, p.158

- "Surah An-Nisa [4:171]". Surah An-Nisa [4:171]. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- "Surah Al-Ma'idah [5:116]". Surah Al-Ma'idah [5:116]. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- "Surah Al-Ma'idah [5:72]". Surah Al-Ma'idah [5:72]. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- "Surah Al-Ma'idah [5:75]". Surah Al-Ma'idah [5:75]. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- "Surah Ali 'Imran [3:59]". Surah Ali 'Imran [3:59]. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- "Surah Al-Anbya [21:91]". Surah Al-Anbya [21:91]. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- Jesus: A Brief History by W. Barnes Tatum 2009 ISBN 1-4051-7019-0 page 217

- The new encyclopedia of Islam by Cyril Glassé, Huston Smith 2003 ISBN 0-7591-0190-6 page 86

- David Richard Thomas Christian Doctrines in Islamic Theology Brill, 2008 ISBN 9789004169357 p. 84

- The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion by Maxine Grossman and Adele Berlin (Mar 14, 2011) ISBN 0199730040 page 698

- The Jewish Annotated New Testament by Amy-Jill Levine and Marc Z. Brettler (Nov 15, 2011) ISBN 0195297709 page 544

- "By Three Days, Live": Messiahs, Resurrection, and Ascent to Heavon in Hazon Gabriel, Israel Knohl, Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- "The First Jesus?". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2010-08-19. Retrieved 2010-08-05.

- Yardeni, Ada (Jan–Feb 2008). "A new Dead Sea Scroll in Stone?". Biblical Archaeology Review. 34 (01).

- van Biema, David; Tim McGirk (2008-07-07). "Was Jesus' Resurrection a Sequel?". Time Magazine. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- Ethan Bronner (2008-07-05). "Tablet ignites debate on messiah and resurrection". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

The tablet, probably found near the Dead Sea in Jordan according to some scholars who have studied it, is a rare example of a stone with ink writings from that era — in essence, a Dead Sea Scroll on stone.

- Matthias Henze (2011). Hazon Gabriel. Society of Biblical Lit. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- Michael S. Heiser (2001). "DEUTERONOMY 32:8 AND THE SONS OF GOD". Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- Markus Bockmuehl; James Carleton Paget, eds. (2007). Redemption and Resistance: The Messianic Hopes of Jews and Christians in Antiquity. A&C Black. pp. 27–28. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- EDWARD M. COOK. "4Q246" (PDF). Bulletin for Biblical Research 5 (1995) 43-66 [© 1995 Institute for Biblical Research]. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- David Flusser (2007). Judaism of the Second Temple Period: Qumran and Apocalypticism. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 249. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- Jerome H. Neyrey (2009). The Gospel of John in Cultural and Rhetorical Perspective. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 313–316.

- translated by Eugene Mason and Text from Joseph and Aseneth H. F. D. Sparks. "The Story of Asenath" and "Joseph and Aseneth". Retrieved 30 January 2014.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

Bibliography

- Borgen, Peder. Early Christianity and Hellenistic Judaism. Edinburgh: T & T Clark Publishing. 1996.

- Brown, Raymond. An Introduction to the New Testament. New York: Doubleday. 1997.

- Essays in Greco-Roman and Related Talmudic Literature. ed. by Henry A. Fischel. New York: KTAV Publishing House. 1977.

- Dunn, J. D. G., Christology in the Making, London: SCM Press. 1989.

- Ferguson, Everett. Backgrounds in Early Christianity. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing. 1993.

- Greene, Colin J. D. Christology in Cultural Perspective: Marking Out the Horizons. Grand Rapids: InterVarsity Press. Eerdmans Publishing. 2003.

- Holt, Bradley P. Thirsty for God: A Brief History of Christian Spirituality. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. 2005.

- Josephus, Flavius. Complete Works. trans. and ed. by William Whiston. Grand Rapids: Kregel Publishing. 1960.

- Letham, Robert. The Work of Christ. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press. 1993.

- Macleod, Donald. The Person of Christ. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press. 1998.

- McGrath, Alister. Historical Theology: An Introduction to the History of Christian Thought. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. 1998.

- Neusner, Jacob. From Politics to Piety: The Emergence of Pharisaic Judaism. Providence, R. I.: Brown University. 1973.

- Norris, Richard A. Jr. The Christological Controversy. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. 1980.

- O'Collins, Gerald. Christology: A Biblical, Historical, and Systematic Study of Jesus. Oxford:Oxford University Press. 2009.

- Pelikan, Jaroslav. Development of Christian Doctrine: Some Historical Prolegomena. London: Yale University Press. 1969.

- _______ The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100–600). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1971.

- Schweitzer, Albert. Quest of the Historical Jesus: A Critical Study of the Progress from Reimarus to Wrede. trans. by W. Montgomery. London: A & C Black. 1931.

- Tyson, John R. Invitation to Christian Spirituality: An Ecumenical Anthology. New York: Oxford University Press. 1999.

- Wilson, R. Mcl. Gnosis and the New Testament. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. 1968.

- Witherington, Ben III. The Jesus Quest: The Third Search for the Jew of Nazareth. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press. 1995.

- _______ “The Gospel of John." in The Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels. ed. by Joel Greene, Scot McKnight and I. Howard