Causeway

A causeway is a track, road or railway on the upper point of an embankment across "a low, or wet place, or piece of water".[1] It can be constructed of earth, masonry, wood, or concrete. One of the earliest known wooden causeways is the Sweet Track in the Somerset Levels, England, that dates from the Neolithic age.[2] Timber causeways may also be described as both boardwalks and bridges.

The Hindenburgdamm Rail Causeway across the Wadden Sea to the island of Sylt in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany | |

| Ancestor | None. (See Ford (crossing)) |

|---|---|

| Related | None. (See Step-stone bridge) |

| Descendant | None. (See Viaduct) |

| Carries | Traffic, Rail, Cyclists, Pedestrians |

| Material | Concrete, Masonry, Earth-fill |

| Movable | No |

| Design effort | medium |

| Falsework required | No |

Etymology

When first used, the word appeared in a form such as "causey way" making clear its derivation from the earlier form "causey". This word seems to have come from the same source by two different routes. It derives ultimately, from the Latin for heel, calx, and most likely comes from the trampling technique to consolidate earthworks.

Originally, the construction of a causeway utilised earth that had been trodden upon to compact and harden it as much as possible, one layer at a time, often by slaves or flocks of sheep. Today, this work is done by machines. The same technique would have been used for road embankments, raised river banks, sea banks and fortification earthworks.

The second derivation route is simply the hard, trodden surface of a path. The name by this route came to be applied to a firmly-surfaced road. It is now little-used except in dialect and in the names of roads which were originally notable for their solidly-made surface. The 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica states "causey, a mound or dam, which is derived, through the Norman-French caucie (cf. modern chaussée),[3] from the late Latin via calciata, a road stamped firm with the feet (calcare, to tread)."[4]

The word is comparable in both meanings with the French chaussée, from a form of which it reached English by way of Norman French. The French adjective, chaussée, carries the meaning of having been given a hardened surface, and is used to mean either paved or shod. As a noun chaussée is used on the one hand for a metalled carriageway, and on the other for an embankment with or without a road.

Other languages have a noun with similar dual meaning. In Welsh, it is sarn. The Welsh is relevant here, as it also has a verb, sarnu, meaning to trample. The trampling and ramming technique for consolidating earthworks was used in fortifications and there is a comparable, outmoded form of wall construction technique, used in such work and known as pisé, a word derived not from trampling but from ramming or tamping. The Welsh word 'cawsai' translates directly to the English word 'causeway'; it is possible that, with Welsh being a lineal linguistic descendant of the original native British tongues, the English word derives from the Welsh.

A transport corridor that is carried instead on a series of arches, perhaps approaching a bridge, is a viaduct; a short stretch of viaduct is called an overpass. The distinction between the terms causeway and viaduct becomes blurred when flood-relief culverts are incorporated, though generally a causeway refers to a roadway supported mostly by earth or stone, while a bridge supports a roadway between piers (which may be embedded in embankments). Some low causeways across shore waters become inaccessible when covered at high tide.

History

The Aztec city-state of Tenochtitlan had causeways supporting roads and aqueducts. One of the oldest engineered roads yet discovered is the Sweet Track in England. Built in 3807 or 3806 BC,[5] the track was a walkway consisting mainly of planks of oak laid end-to-end, supported by crossed pegs of ash, oak, and lime, driven into the underlying peat.

Engineering

The modern embankment may be constructed within a cofferdam: two parallel steel sheet pile or concrete retaining walls, anchored to each other with steel cables or rods. This construction may also serve as a dyke that keeps two bodies of water apart, such as bodies with a different water level on each side, or with salt water on one side and fresh water on the other. This may also be the primary purpose of a structure, the road providing a hardened crest for the dike, slowing erosion in the event of an overflow. It also provides access for maintenance as well perhaps, as a public service.

Examples

Notable causeways include those that connect Singapore and Malaysia (the Johor-Singapore Causeway), Bahrain and Saudi Arabia (25-km long King Fahd Causeway) and Venice to the mainland, all of which carry roadways and railways. In the Netherlands there are a number of prominent dikes which also double as causeways, including the Afsluitdijk, Brouwersdam, and Markerwaarddijk. In Louisiana, two very long bridges, called the Lake Pontchartrain Causeway, stretch across Lake Pontchartrain for almost 38 km, making them the world's longest bridges (if total length is considered instead of span length). They are also the oldest causeways on the Gulf Coast that have never been put out of commission for an extended period of time following a hurricane. In the Republic of Panama a causeway connects the islands of Perico, Flamenco, and Naos to Panama City on the mainland. It also serves as a breakwater for ships entering the Panama Canal.

Causeways are also common in Florida, where low bridges may connect several man-made islands, often with a much higher bridge (or part of a single bridge) in the middle so that taller boats may pass underneath safely. Causeways are most often used to connect the barrier islands with the mainland.

The Churchill Barriers in Orkney are some of the most notable sets of causeways in Europe. Constructed in waters up to 18 metres deep, the four barriers link five islands on the eastern side of the natural harbour at Scapa Flow. They were built during World War II as military defences for the harbour, on the orders of Winston Churchill.

The Estrada do Istmo connecting the islands of Taipa and Coloane in Macau was initially built as a causeway. The sea on both sides of the causeway then became shallower as a result of silting, and mangroves began to conquer the area. Later, land reclamation took place on both sides of the road and the area has subsequently been named Cotai and become home to several casino complexes.

Specific causeways around the world

Various causeways in the world:

- Adam's Bridge, historic causeway which existed till 1480 CE

- Afsluitdijk, Netherlands.

- Canso Causeway, Nova Scotia, Canada (45.6443°N 61.4184°W)

- Colaba Causeway, Mumbai, India[6] 18.91°N 72.81°E

- Courtney Campbell Causeway, Tampa Bay, Florida, United States

- Gaoji Causeway, Xiamen, China

- Hindenburgdamm, Germany (54.8852°N 8.5404°E)

- Johor–Singapore Causeway (1.4520°N 103.7700°E)

- King Fahd Causeway, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia (26.1841°N 50.3241°E)

- Lake Cuitzeo Causeway, Michoacán, Mexico (19.9380°N 101.1547°W)

- Lake Pontchartrain Causeway, Metairie, Louisiana, Southern; Mandeville, Louisiana, Northern.

- Lucin Cutoff railroad causeway across the Great Salt Lake in Utah, USA

- MacArthur Causeway, Florida, United States

- Mahim Causeway, Mumbai, India 19.04871°N 72.83816°E

- Pulaski Skyway

- Robert Moses Causeway, Bay Shore, Long Island, New York, United States ()

- Sanibel Causeway, Sanibel, Florida, United States

- Swarkestone causeway, Derby, England, United Kingdom

- The Causeway, Western Australia

- Venice (45.4535°N 12.2990°E)

- Yolo Causeway, California, USA

Precautions

Causeways affect currents and may therefore be involved in beach erosion or changed deposition patterns; this effect has been a problem at the Hindenburgdamm in northern Germany. During hurricane seasons, the winds and rains of approaching tropical storms—as well as waves generated by the storm in the surrounding bodies of water—make traversing causeways problematic at best and impossibly dangerous during the fiercest parts of the storms. For this reason (and related reasons, such as the need to minimize traffic jams on both the roads approaching the causeway and the causeway itself), emergency evacuation of island residents is a high priority for local, regional, and even national authorities.

Gallery

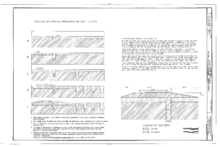

Aerial view of the Lucin Cutoff trestle before removal. The 1950s causeway can be seen to the right of the trestle.

Aerial view of the Lucin Cutoff trestle before removal. The 1950s causeway can be seen to the right of the trestle. The causeway to Antelope Island in the Great Salt Lake, Utah

The causeway to Antelope Island in the Great Salt Lake, Utah

- The Sorell Causeway in Tasmania, Australia

Lake Pontchartrain Causeway bridge in New Orleans

Lake Pontchartrain Causeway bridge in New Orleans Causeway across Colwyn Bay Beach, Wales, United Kingdom

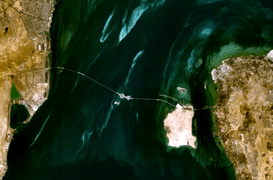

Causeway across Colwyn Bay Beach, Wales, United Kingdom The King Fahd Causeway from satellite photo

The King Fahd Causeway from satellite photo Causeway in St. George's, Bermuda

Causeway in St. George's, Bermuda

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to causeways. |

References

- Oxford English Dictionary

- Williams, Robin; Williams, Romey (1992). The Somerset Levels. Bradford on Avon: Ex Libris Press. pp. 35–36. ISBN 0-948578-38-6.

- Wedgwood, Hensleigh (1855). "On False Etymologies". Transactions of the Philological Society (6): 66.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- Brunning, Richard (February 2001). "The Somerset Levels". Current Archaeology. XV (4) (172 (Special issue on Wetlands)): 139–143.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Colaba Causeway

- Oxford English Dictionary. 1971. ISBN 0-19-861212-5.

- Collins Robert French Dictionary, 5th edn. 1998. ISBN 0-00-470526-2.

- Nouveau Petit Larousse Illustré, Paris. 1934.

- Grape, W. The Bayeux Tapestry. Prestel, Munich and New York. 1994. ISBN 3-7913-1365-7.

- Evans, H.M. and Thomas, W.O. The New Welsh Dictionary (Y Geiriadur Newydd). Llyfrau'r Dryw, Llandybie. 1953.