Sieve analysis

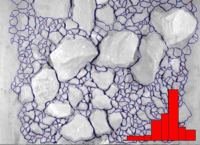

A sieve analysis (or gradation test) is a practice or procedure used (commonly used in civil engineering) to assess the particle size distribution (also called gradation) of a granular material by allowing the material to pass through a series of sieves of progressively smaller mesh size and weighing the amount of material that is stopped by each sieve as a fraction of the whole mass.

| Granulometry | |

|---|---|

| |

| Basic concepts | |

| Particle size · Grain size Size distribution · Morphology | |

| Methods and techniques | |

| Mesh scale · Optical granulometry Sieve analysis · Soil gradation | |

Related concepts | |

| Granulation · Granular material Mineral dust · Pattern recognition Dynamic light scattering | |

The size distribution is often of critical importance to the way the material performs in use. A sieve analysis can be performed on any type of non-organic or organic granular materials including sands, crushed rock, clays, granite, feldspars, coal, soil, a wide range of manufactured powders, grain and seeds, down to a minimum size depending on the exact method. Being such a simple technique of particle sizing, it is probably the most common.[1]

Procedure

A gradation test is performed on a sample of aggregate in a laboratory. A typical sieve analysis involves a nested column of sieves with wire mesh cloth (screen). See the separate Mesh (scale) page for details of sieve sizing.

A representative weighed sample is poured into the top sieve which has the largest screen openings. Each lower sieve in the column has smaller openings than the one above. At the base is a round pan, called the receiver.

The column is typically placed in a mechanical shaker. The shaker shakes the column, usually for some fixed amount of time. After the shaking is complete the material on each sieve is weighed. The mass of the sample of each sieve is then divided by the total mass to give a percentage retained on each sieve. The size of the average particle on each sieve is then analysed to get a cut-off point or specific size range, which is then captured on a screen.

The results of this test are used to describe the properties of the aggregate and to see if it is appropriate for various civil engineering purposes such as selecting the appropriate aggregate for concrete mixes and asphalt mixes as well as sizing of water production well screens.

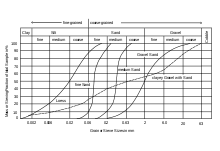

The results of this test are provided in graphical form to identify the type of gradation of the aggregate. The complete procedure for this test is outlined in the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) C 136[2] and the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) T 27[3]

A suitable sieve size for the aggregate underneath the nest of sieves to collect the aggregate that passes through the smallest. The entire nest is then agitated, and the material whose diameter is smaller than the mesh opening pass through the sieves. After the aggregate reaches the pan, the amount of material retained in each sieve is then weighed.[4]

Preparation

In order to perform the test, a sufficient sample of the aggregate must be obtained from the source. To prepare the sample, the aggregate should be mixed thoroughly and be reduced to a suitable size for testing. The total mass of the sample is also required.[4]

Results

The results are presented in a graph of percent passing versus the sieve size. On the graph the sieve size scale is logarithmic. To find the percent of aggregate passing through each sieve, first find the percent retained in each sieve. To do so, the following equation is used,

%Retained = ×100%

where WSieve is the mass of aggregate in the sieve and WTotal is the total mass of the aggregate. The next step is to find the cumulative percent of aggregate retained in each sieve. To do so, add up the total amount of aggregate that is retained in each sieve and the amount in the previous sieves. The cumulative percent passing of the aggregate is found by subtracting the percent retained from 100%.

%Cumulative Passing = 100% - %Cumulative Retained.

The values are then plotted on a graph with cumulative percent passing on the y axis and logarithmic sieve size on the x axis.[4]

There are two versions of the %Passing equations. the .45 power formula is presented on .45 power gradation chart, whereas the more simple %Passing is presented on a semi-log gradation chart. version of the percent passing graph is shown on .45 power chart and by using the .45 passing formula.

- .45 power percent passing formula

% Passing = Pi = x100%

Where:

SieveLargest - Largest diameter sieve used in (mm).

Aggregatemax_size - Largest piece of aggregate in the sample in (mm).

- Percent passing formula

%Passing = x100%

Where:

WBelow - The total mass of the aggregate within the sieves below the current sieve, not including the current sieve's aggregate.

WTotal - The total mass of all of the aggregate in the sample.

Methods

There are different methods for carrying out sieve analyses, depending on the material to be measured.

Throw-action

Here a throwing motion acts on the sample. The vertical throwing motion is overlaid with a slight circular motion which results in distribution of the sample amount over the whole sieving surface. The particles are accelerated in the vertical direction (are thrown upwards). In the air they carry out free rotations and interact with the openings in the mesh of the sieve when they fall back. If the particles are smaller than the openings, they pass through the sieve. If they are larger, they are thrown.. The rotating motion while suspended increases the probability that the particles present a different orientation to the mesh when they fall back again, and thus might eventually pass through the mesh. Modern sieve shakers work with an electro-magnetic drive which moves a spring-mass system and transfers the resulting oscillation to the sieve stack. Amplitude and sieving time are set digitally and are continuously observed by an integrated control-unit. Therefore, sieving results are reproducible and precise (an important precondition for a significant analysis). Adjustment of parameters like amplitude and sieving time serves to optimize the sieving for different types of material. This method is the most common in the laboratory sector.[5]

Horizontal

In horizontal sieve shaker the sieve stack moves in horizontal circles in a plane. Horizontal sieve shakers are preferably used for needle-shaped, flat, long or fibrous samples, as their horizontal orientation means that only a few disoriented particles enter the mesh and the sieve is not blocked so quickly. The large sieving area enables the sieving of large amounts of sample, for example as encountered in the particle-size analysis of construction materials and aggregates.

Tapping

A horizontal circular motion overlies a vertical motion which is created by a tapping impulse. These motional processes are characteristic of hand sieving and produce a higher degree of sieving for denser particles (e.g. abrasives) than throw-action sieve shakers.

Wet

Most sieve analyses are carried out dry. But there are some applications which can only be carried out by wet sieving. This is the case when the sample which has to be analysed is e.g. a suspension which must not be dried; or when the sample is a very fine powder which tends to agglomerate (mostly < 45 µm) – in a dry sieving process this tendency would lead to a clogging of the sieve meshes and this would make a further sieving process impossible. A wet sieving process is set up like a dry process: the sieve stack is clamped onto the sieve shaker and the sample is placed on the top sieve. Above the top sieve a water-spray nozzle is placed which supports the sieving process additionally to the sieving motion. The rinsing is carried out until the liquid which is discharged through the receiver is clear. Sample residues on the sieves have to be dried and weighed. When it comes to wet sieving it is very important not to change the sample in its volume (no swelling, dissolving or reaction with the liquid).

Air Circular Jet

Air jet sieving machines are ideally suited for very fine powders which tend to agglomerate and cannot be separated by vibrational sieving. The reason for the effectiveness of this sieving method is based on two components: A rotating slotted nozzle inside the sieving chamber and a powerful industrial vacuum cleaner which is connected to the chamber. The vacuum cleaner generates a vacuum inside the sieving chamber and sucks in fresh air through the slotted nozzle. When passing the narrow slit of the nozzle the air stream is accelerated and blown against the sieve mesh, dispersing the particles. Above the mesh, the air jet is distributed over the complete sieve surface and is sucked in with low speed through the sieve mesh. Thus the finer particles are transported through the mesh openings into the vacuum cleaner.

Types of gradation

- A Dense gradation

- A dense gradation refers to a sample that is approximately of equal amounts of various sizes of aggregate. By having a dense gradation, most of the air voids between the material are filled with particles. A dense gradation will result in an even curve on the gradation graph.[6]

- Narrow gradation

- Also known as uniform gradation, a narrow gradation is a sample that has aggregate of approximately the same size. The curve on the gradation graph is very steep, and occupies a small range of the aggregate.[4]

- Gap gradation

- A gap gradation refers to a sample with very little aggregate in the medium size range. This results in only coarse and fine aggregate. The curve is horizontal in the medium size range on the gradation graph.[4]

- Open gradation

- An open gradation refers an aggregate sample with very little fine aggregate particles. This results in many air voids, because there are no fine particles to fill them. On the gradation graph, it appears as a curve that is horizontal in the small size range.[4]

- Rich gradation

- A rich gradation refers to a sample of aggregate with a high proportion of particles of small sizes.[6]

Types of sieves

- Woven wire mesh sieves

Woven wire mesh sieves are according to technical requirements of ISO 3310-1.[7] These sieves usually have nominal aperture ranging from 20 micrometers to 3.55 millimeters, with diameters ranging from 100 to 450 millimeters.

- Perforated plate sieves

Perforated plate sieves conform to ISO 3310-2 and can have round or square nominal apertures ranging from 1 millimeter to 125 millimeters.[8] The diameters of the sieves range from 200 to 450 millimeters.

- American standard sieves

American standard sieves also known as ASTM sieves conform to ASTM E11 standard.[9] The nominal aperture of these sieves range from 20 micrometers to 200 millimeters, however these sieves have only 8 inches (203 mm) and 12 inches (305 mm) diameter sizes.

Limitations of sieve analysis

Sieve analysis has, in general, been used for decades to monitor material quality based on particle size. For coarse material, sizes that range down to #100 mesh (150μm), a sieve analysis and particle size distribution is accurate and consistent.

However, for material that is finer than 100 mesh, dry sieving can be significantly less accurate. This is because the mechanical energy required to make particles pass through an opening and the surface attraction effects between the particles themselves and between particles and the screen increase as the particle size decreases. Wet sieve analysis can be utilized where the material analyzed is not affected by the liquid - except to disperse it. Suspending the particles in a suitable liquid transports fine material through the sieve much more efficiently than shaking the dry material.

Sieve analysis assumes that all particle will be round (spherical) or nearly so and will pass through the square openings when the particle diameter is less than the size of the square opening in the screen. For elongated and flat particles a sieve analysis will not yield reliable mass-based results, as the particle size reported will assume that the particles are spherical, where in fact an elongated particle might pass through the screen end-on, but would be prevented from doing so if it presented itself side-on.

Properties

Gradation affects many properties of an aggregate, including bulk density, physical stability and permeability. With careful selection of the gradation, it is possible to achieve high bulk density, high physical stability, and low permeability. This is important because in pavement design, a workable, stable mix with resistance to water is important. With an open gradation, the bulk density is relatively low, due to the lack of fine particles, the physical stability is moderate, and the permeability is quite high. With a rich gradation, the bulk density will also be low, the physical stability is low, and the permeability is also low. The gradation can be affected to achieve the desired properties for the particular engineering application.[6]

Engineering applications

Gradation is usually specified for each engineering application it is used for. For example, foundations might only call for coarse aggregates, and therefore an open gradation is needed. Sieve analysis determines the particle size distribution of a given soil sample and hence helps in easy identification of a soil's mechanical properties. These mechanical properties determine whether a given soil can support the proposed engineering structure. It also helps determine what modifications can be applied to the soil and the best way to achieve maximum soil strength.

References

- p231 in "Characterisation of bulk solids" by Donald Mcglinchey, CRC Press, 2005.

- ASTM International - Standards Worldwide. (2006). ASTM C136-06. http://www.astm.org/cgi-bin/SoftCart.exe/DATABASE.CART/REDLINE_PAGES/C136.htm?E+mystore

- AASHTO The Voice of Transportation. T0 27. (2006). http://bookstore.transportation.org/item_details.aspx?ID=659

- Pavement Interactive. Gradation Test. (2007). http://pavementinteractive.org/index.php?title=Gradation_Test

- Texas Department of Transportation (January 2016). "Test Procedure for Sieve Analysis of Fine and Coarse Aggregates" (PDF). Texas DOT. Retrieved 2016-12-24.

- M.S. Mamlouk and J.P. Zaniewski, Materials for Civil and Construction Engineers, Addison-Wesley, Menlo Park CA, 1999

- ISO/TC 24/SC 8. Test sieves -- Technical requirements and testing -- Part 1: Test sieves of metal wire cloth. ISO 3310-1:2000. ISO. p. 15.

- ISO/TC 24/SC 8. Test sieves -- Technical requirements and testing -- Part 2: Test sieves of perforated metal plate. ISO 3310-2:2013. ISO. p. 9.

- Subcommittee: E29.01. Standard Specification for Woven Wire Test Sieve Cloth and Test Sieves. ASTM E11 - 13. ASTM International. p. 9.