Battle of Ning-Jin

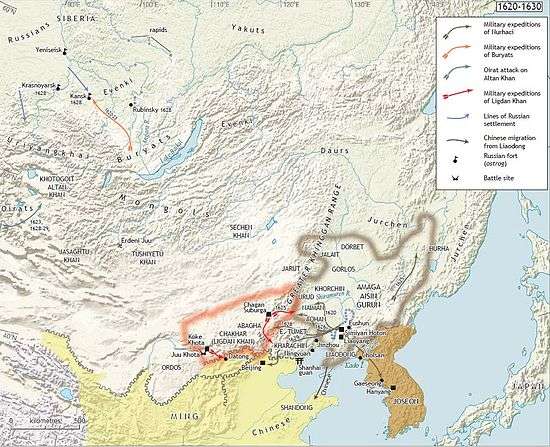

The Battle of Ning-Jin was a military conflict between the Later Jin and Ming dynasty. In the spring of 1627 the Jin khan Hong Taiji invaded Ming territory in Liaoning under the pretext of illegal construction on Jin lands.

| Battle of Ning-Jin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Qing conquest of the Ming | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Later Jin | Ming dynasty | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Hong Taiji Jirgalang (WIA) Ajige Hooge Daišan Manggūltai Amin |

Zhao Shuaijiao Man Gui (WIA) You Shilu Zu Dashou Yuan Chonghuan Zuo Fu Zhu Mei You Shiwei Ji Yong | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 40,000[1] |

Jinzhou: 30,000[1] Man Gui: 30,000[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| several thousand | unknown | ||||||

Background

The Jin khan Nurhaci was wounded in the Battle of Ningyuan the previous year and died. His successor Hong Taiji ordered Amin to attack the kingdom of Joseon (Korea). He himself led a force of 40,000 to attack the Ming city of Jinzhou.[1]

Course of battle

The Later Jin invaded Ming territory in Liaoning under the pretext of illegal construction on Jin lands. The Ming court immediately dispatched a relief army of 30,000.[1]

Hong Taiji led a force of 40,000 to Jinzhou, where he began negotiations with Ming. When Ming refused to respond, he assaulted the city. The battle was close and at one point it appeared that the western guard tower was about to fall, but the commander Zhao Shuaijiao rallied the defenders in that area and repelled the Jin soldiers. After half a day of fighting, Hong Taiji sounded the retreat and pulled back out of the range of Ming cannons.[2]

After several days of successful resistance by Jinzhou, Hong Taiji decided to try his luck at Ningyuan. As Hong Taiji approached Ningyuan, he was intercepted by a Ming army led by Man Gui, You Shilu, and Zu Dashou. The two armies engaged in combat, but it soon became apparent that the Jin were at a severe disadvantage as Yuan Chonghuan had expanded the defensive network from Ningyuan, and Ming reinforcements rushed out from defensive fortifications to attack. Meanwhile, Yuan directed cannoneers on top of Ningyuan's walls who assisted the ground forces by bombarding the enemies. The Jin army disengaged after losing several thousand men and retreated to Jinzhou, where Hong Taiji tried once again to take the city.[2]

As Ming cannons opened fire on the Jin army, a contingent of Ming cavalry engaged the enemies from the rear, forcing them to retreat with yet more casualties. After rallying his army, Hong Taiji attempted another assault on Jinzhou, this time attacking from the south while feigning diversionary assaults from the other three sides. This futile endeavor ended badly and the Jin suffered some two to three thousand casualties before retreating.[2]

Aftermath

Hong Taiji learned the value of artillery and endeavored to obtain more firearm units for his army. In the immediate aftermath however he was occupied with famine and banditry in the Jin realm, which forced him to distribute relief supplies.

Despite the Ming success in battle, Yuan Chonghuan was impeached for lack of agency, engaging with the Jin in peace talks, and allowing them to invade the kingdom of Joseon, for which he was dismissed from office. He was eventually reinstated again after the reigning Tianqi Emperor died and the Chongzhen Emperor succeeded him on 2 October 1627. In the summer of 1628 Yuan announced that he could recover all of Liaodong in just five years if the court followed his plans.[2]

Unfortunately for him, by this time Ming treasuries had been nearly tapped out and the Taicang vault was left with only seven million taels.[3] The Ming realm was also suffering from natural disasters in Shaanxi, Shanxi and Henan. In 1627 widespread drought in Shaanxi resulted in mass starvation as harvests failed and people turned to cannibalism. Natural disasters in Shaanxi were not unusual, and in the last 60 years of the Ming, there was not a single year in which Shaanxi did not experience a natural disaster. The entire region was a natural disaster zone. Shanxi too suffered from windstorms, earthquakes, and famines. In the south, Henan also experienced starvation and it was said that "grains of rice became as precious as pearls."[4] Chongzhen's petty and mercurial ways exacerbated the situation by constantly switching grand secretaries, which prevented a coherent government response from coalescing. Chongzhen's reign alone saw around 50 grand secretaries appointed to the post, representing two thirds of all holders of that post throughout the entire Ming dynasty.[5]

To prevent further depletion of the imperial treasury, Chongzhen cut funding for the Ming postal service, which saw the mass unemployment of large numbers of men from the central and northern provinces around the Yellow River region. This in turn contributed to the overall deterioration of government control and the formation of bandit groups, which became endemic in the last decades of the Ming. In the spring of 1628, Wang Jiayin started a revolt in Shaanxi with some 6,000 followers, one of whom was Zhang Xianzhong, who would go on to depopulate Sichuan in the future. The rebellion posed no threat to the Ming army, but due to the rugged mountain terrain of Shaanxi, the Ming pacification army of 17,000 was unable to effectively root out the rebels.[6]

Another bandit leader Gao Yingxiang rose up in revolt and joined Wang Jiayin soon after. In early 1629 the veteran anti-rebel leader Yang He was called into service and made Supreme Commander of the Three Border Regions. What he found was that situations were even more dire than they appeared. Salaries for soldiers of Shaanxi were three years in arrears, and their own soldiers were deserting to join the rebels. Yang was unable to suppress Wang Jiayin's rebels, who took several isolated fortresses as late as 1630. Yang's policy of amnesty for surrendered peasants was generally ineffective. Once surrendered, the peasants would go back to their homes and join other rebel bands. Despite Ming victories in battle, peasant rebellions would remain a major problem for the remainder of the Ming dynasty. Yang He was eventually impeached and arrested for ineffectiveness. He was replaced with Hong Chengchou who would later defect to the Qing dynasty.[7]

As a result, Yuan Chonghuan was only allotted 40 percent of the funds he had requested.[5]

References

- Swope 2014, p. 67.

- Swope 2014, p. 68.

- Swope 2014, p. 71.

- Swope 2014, p. 76.

- Swope 2014, p. 72.

- Swope 2014, pp. 76–77.

- Swope 2014, pp. 77–79.

Bibliography

- Swope, Kenneth (2014), The Military Collapse of China's Ming Dynasty, Routledge

- Wakeman, Frederic (1985), The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-Century China, 1, University of California Press