Battle of Guangning

The Battle of Guanging was a military conflict between the Manchu forces of the Later Jin and the Ming dynasty of China. It occurred at and around the Ming's northern city of Guangning (now Beizhen, Liaoning), which fell to the Later Jin in 1622.

| Battle of Guangning | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Qing conquest of the Ming | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Later Jin | Ming dynasty | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Nurhaci Li Yongfang Hong Taiji Daišan |

Wang Huazhen Xiong Tingbi Bao Chengxian Luo Yiguan † Sun Degong | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| unknown | 36,000+[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| at least 6,000[3] | 16,000+[2] | ||||||

Background

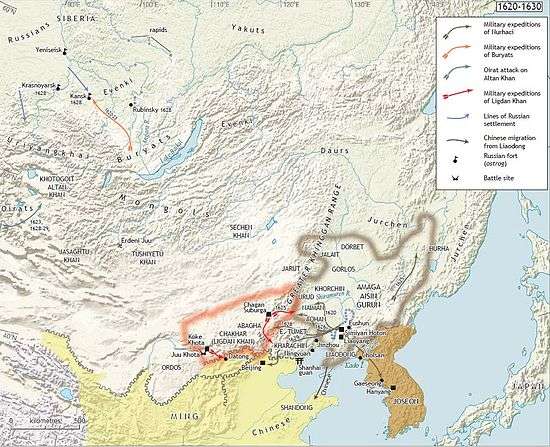

In Sichuan and Guizhou a major rebellion by indigenous peoples had broken out the previous year, and the Ming dynasty was thrown into a major rebel crisis. Meanwhile in Liaoning, Wang Huazhen, Vice Censor-Chief of the Right and Touring Pacification Commissioner of Guangning, proposed hiring 400,000 Mongols to attack the Jurchens. The officials at the Ming court thought this was a dumb idea and refused the proposal.[4][3]

As of 1622 the Ming dynasty had spent 21,188,366 taels on the war in Liaodong over a three year period. With the allotted funds for weapons manufacturing, 25,134 cannons, 6,425 muskets, 8,252 small guns, and 4,090 culverins had been produced for a total of 43,901 firearms. In terms of cold weapons, 98,547 polearms and swords, 26,214 great "horse decapitator" swords, 42,800 bows, 1,000 great axes, 2,284,000 arrows, 180,000 fire arrows, 64,000 bow strings, and hundreds of transport carts were produced.[5]

Course of battle

Jin forces attacked Fort Xiping, situated west of the Liu River, one of the minor tributaries of the Liao River. Their initial advance was checked by Ming forces who repelled the invaders with cannon fire.[3]

Wang Huazhen, charged with the defense of Guangning, sent Bao Chengxian to intercept the enemy. Ming forces engaged in battle with the Jin army and lost. Bao managed to evade capture and escaped. Upon receiving news of their defeat, Wang abandoned Guangning, leaving Sun Degong in charge of the city, and fled to Dalinghe.[1]

Luo Yiguan, the commander of Fort Xiping, had an unruly subordinate who wanted to attack the Jurchens, so he did. He was defeated and retreated back to the fortress.[3]

The Ming defector Li Yongfang besieged Fort Xiping. Fort garrisons put up a stout defense and Luo personally cursed Li as a traitor. So many attackers died that piles of their bodies were reported to have reached the top of the walls. Eventually the defenders ran out of gunpowder and ammunition, at which point Luo bowed towards Beijing and said, "Your minister has exhausted himself," before committing suicide by slitting his throat. What remained of Fort Xiping's 3,000 garrisons were slaughtered, but the Jin army had suffered 6,000 casualties in the process.[6]

The Jin khan Nurhaci then intercepted a Ming relief force of 30,000 and routed them, killing a third of their men.[3]

Meanwhile, the Ming's Mongol allies were busy looting the area around Guanging, which had already been emptied of people, who fled further south seeking refuge.[7]

Sun Degong surrendered Guangning to the Jin, after which Bao Chengxian also came forward and surrendered.[1]

Nurhaci's sons Hong Taiji and Daišan took Yizhou and slaughtered its 3,000 strong garrison.[7]

Aftermath

Nurhaci returned to Liaoyang to recuperate. Sun Degong became a mobile corps commander accompanying the White Banner, and led other Ming defectors to garrison Yizhou.

Wang Huazhen rendezvoused with Xiong Tingbi at Dalinghe. From there Wang retreated with the aid of Xiong's soldiers past the Shanhai Pass into Ming territory. Both Wang and Xiong were impeached and eventually arrested. Xiong Tingbi was executed in 1625 and Wang Huazhen was executed in 1632.[7]

Ming commander Zu Dashou retreated to Juehua Island.[7]

Mao Wenlong was appointed commander-in-charge of Pacifying Liao.[7]

Sun Chengzong was appointed military commissioner. He immediately requested 200,000 taels in cash, which the court eunuch Wei Zhongxian opposed, but was ultimately provided for on command of the emperor. The emperor also allocated 30,000 taels for the construction of war carts. Sun took on a defensive approach and promoted his stance to the court as the only realistic response to Jin aggression. Sun chastised the court officials for having no knowledge of military matters yet constantly meddling in matters of strategic importance. However he also acknowledged the problem of military officials impinging on the authority of civil officials, and neither were ideal or desirable.[8]

The frontier situation is dire. Troops have been amassed, but not trained and military supplies have not arrived. You need generals to lead the troops but civil officials to coordinate training. Generals must oversee ranks, but a civil official must determine their use. You must use military officials to defend the frontiers but every day they should consult with civil officials in their tent. So the frontier should be entrusted to a xunfu and a jinglue and the decision to attack or defend should emanate from the court.[8]

— Sun Chengzong

Sun recommended the appointment of men such as Sun Yuanhua and Yuan Chonghuan, who would play a pivotal role in the Battle of Ningyuan. Yuan Chonghuan was made Inspector of the Army at Shanhai Pass. Ningyuan, located southwest of Guangning, was made the frontier base in the northeast.[9]

Wang Zaijin continued to propose a Ming-Mongol alliance, and even requested 1.2 million taels to hire Mongols to attack the Jin. He was eventually reassigned to Nanjing as Military Commissioner of auxiliary administration.[10]

References

- Wakeman 1985, p. 67.

- Swope 2014, p. 44-45.

- Swope 2014, p. 44.

- Swope 2014, p. 41.

- Swope 2014, p. 49.

- Swopoe 2014, p. 44.

- Swope 2014, p. 45.

- Swope 2014, p. 50.

- Swope 2014, p. 45-46.

- Swope 2014, p. 51.

Bibliography

- Swope, Kenneth (2014), The Military Collapse of China's Ming Dynasty, Routledge

- Wakeman, Frederic (1985), The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-Century China, 1, University of California Press