1992 Summer Olympics

The 1992 Summer Olympics (Spanish: Juegos Olímpicos de Verano de 1992, Catalan: Jocs Olímpics d'estiu de 1992), officially known as the Games of the XXV Olympiad, was an international multi-sport event held in Barcelona, Spain from 25 July to 9 August 1992.

| |||

| Host city | Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Motto | Friends For Life (Spanish: Amigos Para Siempre, Catalan: Amics Per Sempre) | ||

| Nations | 169 | ||

| Athletes | 9,356 (6,652 men, 2,704 women) | ||

| Events | 257 in 25 sports (34 disciplines) | ||

| Opening | 25 July | ||

| Closing | 9 August | ||

| Opened by | |||

| Cauldron | |||

| Stadium | Estadi Olímpic de Montjuïc | ||

| Summer | |||

| |||

| Winter | |||

| |||

| Part of a series on |

|

Beginning in 1994, the International Olympic Committee decided to hold the Summer and Winter Olympics in alternating even-numbered years. The 1992 Summer Olympics was the last occasion for the Summer and Winter Olympics to be staged in the same year.[2] This Olympiad was the first since the end of the Cold War, and was unaffected by boycotts for the first time since the 1972 Olympiad.[3]

The Unified Team topped the medal table, winning 45 gold and 112 overall medals.

Host city selection

Barcelona is the second-largest city in Spain and the capital of the autonomous community of Catalonia, and the hometown of then-IOC president Juan Antonio Samaranch. The city was also a host for the 1982 FIFA World Cup. On 17 October 1986, Barcelona was selected to host the 1992 Summer Olympics over Amsterdam, Netherlands; Belgrade, Yugoslavia; Birmingham, United Kingdom; Brisbane, Queensland, Australia; and Paris, France, during the 91st IOC Session in Lausanne, Switzerland.[4] With 85 out of 89 members of the IOC voting by secret ballot, Barcelona won a majority of 47 votes. Samaranch abstained from voting. In the same IOC meeting, Albertville, France, won the right to host the 1992 Winter Games.[5]

Barcelona had previously bid for the 1936 Summer Olympics, that were held in Berlin.

| 1992 Summer Olympics bidding results[6] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | NOC Name | Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | ||

| Barcelona | 29 | 37 | 47 | |||

| Paris | 19 | 20 | 23 | |||

| Brisbane | 11 | 9 | 10 | |||

| Belgrade | 13 | 11 | 5 | |||

| Birmingham | 8 | 8 | — | |||

| Amsterdam | 5 | — | — | |||

Highlights

- At the opening ceremony, Greek mezzo-soprano Agnes Baltsa sang "Romiossini" as the Olympic flag was paraded around the stadium. Alfredo Kraus later sang the Olympic Hymn in Spanish, Catalan and French, as the flag was hoisted.

- The Olympic cauldron was ignited using a flaming arrow, lit from the flame of the Olympic torch. It was shot by Paralympic archer Antonio Rebollo, who aimed the arrow over the top of the cauldron to ignite the gas emanating from it. The arrow landed outside the stadium.[7] This unusual method for lighting the cauldron had been carefully designed to avoid any chance of the arrow landing in the stadium if Rebollo missed his target.[8][9]

- South Africa rejoined the Summer Olympics having been banned for its apartheid policy after the 1960 Summer Olympics. The Women's 10,000 metres event was hotly contested. White South African runner Elana Meyer and black Ethiopian runner Derartu Tulu (winner) ran hand-in-hand in a victory lap.[10]

- Germany sent a unified team having reunified in 1990, the last such team was at the 1964 Summer Olympics.

- As the Soviet Union was dissolved in 1991, the Baltic nations of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, sent their own teams for the first time since 1936. The other former Soviet republics preferred to compete together as the Unified Team, which consisted of present-day Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan. The Unified Team finished first in the medal standings, edging the United States.

- The separation of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia led to the Olympic debuts of Croatia, Slovenia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Due to United Nations sanctions, athletes from the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia were not allowed to participate with their own team. However, some individual athletes competed under the Olympic flag as Independent Olympic Participants.

- In basketball, the admittance of NBA players led to the formation of the "Dream Team" of the United States, featuring Michael Jordan, Magic Johnson, Larry Bird and other NBA stars. Prior to 1992, only European and South American professionals were allowed to compete, while the Americans used college players. The Dream Team won the gold medal and was inducted as a unit into the Basketball Hall of Fame in 2010.[11]

- Fermín Cacho won the 1,500 metres in his home country, earning Spain's first-ever Olympic gold medal in a running event.[12]

- Chinese diver Fu Mingxia, age 13, became one of the youngest Olympic gold medalists of all time.

- In men's artistic gymnastics, Vitaly Scherbo from Belarus, (representing the Unified Team), won six gold medals, including four in a single day. Scherbo tied Eric Heiden's record for individual gold medals at a single Olympics, winning five medals in an individual event (Michael Phelps would later equal this record in 2008).

- In women's artistic gymnastics, Tatiana Gutsu took gold in the All-Around competition edging the United States' Shannon Miller.

- Russian swimmers (competing for the Unified Team) dominated the men's freestyle events, with Alexander Popov and Yevgeny Sadovyi each winning two events. Sadovyi also won in the relays.

- Evelyn Ashford won her fourth Olympic gold medal in the 4×100-metre relay, making her one of only four female athletes to have achieved this in history.

- The young Krisztina Egerszegi of Hungary won three individual swimming gold medals.

- In women's 200 metre breaststroke, Kyoko Iwasaki of Japan won a gold medal at age of 14 years and six days, making her the youngest-ever gold medalist in swimming competitions at the Olympics.

- Algerian athlete Hassiba Boulmerka, who was frequently criticized by Muslim groups in Algeria who thought she showed too much of her body when racing, received death threats[13] and was forced to move to Europe to train, won the 1,500 metres, also holding the African women's record in this distance.

- After being demonstrated in six previous Summer Olympic Games, baseball officially became an Olympic sport. Badminton and women's judo also became part of the Olympic program, while slalom canoeing returned to the Games after a 20-year absence.

- Roller hockey, Basque pelota, and taekwondo were all demonstrated at the 1992 Summer Olympics.

- Several of the U.S. men's volleyball gold medal team from the 1988 Olympics returned to vie for another medal. In the preliminary round, they lost a controversial match to Japan, sparking them to shave their heads in protest. This notably included player Steve Timmons, sacrificing his trademark red flattop for the protest. The U.S. team ultimately progressed to the playoffs and won bronze.

- Mike Stulce of the United States won the men's shot put, beating the heavily favored Werner Günthör of Switzerland.

- On the 20th anniversary of the Munich massacre and the 500th anniversary of the Alhambra Decree, Yael Arad became the first Israeli to win an Olympic medal, winning a silver medal in judo. The next day, Oren Smadja became Israel's first male medalist, winning a bronze in the same sport.

- Derek Redmond of Great Britain tore a hamstring during a 400-meter semi-final heat. As he struggled to finish the race, his father entered the track without credentials and helped him complete the race, to a standing ovation from the crowd.

- Gail Devers came into the 100 meters hurdles as the favorite. Though her Olympic history shows her winning the 100 meters dash twice, the first time earlier in this Olympics, she primarily made her career as a hurdler. And true to form, Devers had a commanding lead in this race, until the final hurdle. Devers came up short and hit the hurdle, foot first, hard, knocking her off balance. She stumbled toward the finish line, falling on the last step, but still finished fifth, .001 out of fourth place.

- Jennifer Capriati won the singles tennis competition at the age of 16. She had previously earned a spot in the semifinals of two grand slams at the age of 14.

- Two gold medals were awarded in solo synchronized swimming after a judge inadvertently entered the score of "8.7" instead of the intended "9.7" in the computerized scoring system for one of Sylvie Fréchette's figures. This error ultimately placed Fréchette second, leaving Kristen Babb-Sprague for the gold medal. Following an appeal FINA awarded Fréchette a gold medal, replacing her silver medal and leaving the two swimmers both with gold.[14]

- Indonesia won its first-ever gold medal, after winning a silver medal at 1988 Olympics. Susi Susanti won the gold in badminton women's singles after defeating Bang Soo-hyun in the final round. Alan Budikusuma won the badminton men's singles competition, earning a second gold medal for Indonesia. Several years later, Susanti and Budikusuma married and she received the nickname golden bride or Olympic bride.

Records

Venues

- Montjuïc Area:

- Cross-country course – modern pentathlon (running)

- Estadi Olímpic de Montjuïc – opening/closing ceremonies, athletics

- Palau Sant Jordi – gymnastics (artistics), volleyball (final), and handball (final)

- Piscines Bernat Picornell – modern pentathlon (swimming), swimming, synchronized swimming, and water polo (final)

- Piscina Municipal de Montjuïc – diving and water polo

- Institut National d'Educació Física de Catalunya – wrestling

- Mataró – athletics (marathon start)

- Palau dels Esports de Barcelona – gymnastics (rhythmic) and volleyball

- Palau de la Metal·lúrgia – fencing, modern pentathlon (fencing)

- Pavelló de l'Espanya Industrial – weightlifting

- Walking course – athletics (walks)

- Diagonal Area:

- Camp Nou – football (final)

- Palau Blaugrana – judo, roller hockey (demonstration final), and taekwondo (demonstration)

- Estadi de Sarrià – football

- Real Club de Polo de Barcelona – equestrian (dressage, jumping, eventing final), modern pentathlon (riding)

- Vall d'Hebron Area:

- Archery Field – archery

- Pavelló de la Vall d'Hebron – Basque pelota (demonstration) and volleyball

- Tennis de la Vall d'Hebron – tennis

- Velodrome – cycling (track)

- Parc de Mar Area

- Estació del Nord Sports Hall – table tennis

- Olympic Harbour – sailing

- Pavelló de la Mar Bella – badminton

- Subsites

- A-17 highway – cycling (road team time trial)

- Banyoles Lake – rowing

- Camp Municipal de Beisbol de Viladecans – baseball

- Canal Olímpic de Catalunya – canoeing (sprint)

- Circuit de Catalunya – cycling (road team time trial start/ finish)

- Club Hípic El Montayá – equestrian (dressage, eventing endurance)

- Estadi de la Nova Creu Alta – football

- Estadi Olímpic de Terrassa – field hockey

- Estadio Luís Casanova – football

- La Romareda – football

- L'Hospitalet de Llobregat Baseball Stadium – baseball (final)

- Mollet del Vallès Shooting Range – modern pentathlon (shooting), shooting

- Palau D'Esports de Granollers – handball

- Parc Olímpic del Segre – canoeing (slalom)

- Pavelló Club Joventut Badalona – boxing

- Pavelló de l'Ateneu de Sant Sadurní – roller hockey (demonstration)

- Pavelló del Club Patí Vic – roller hockey (demonstration)

- Pavelló d'Esports de Reus – roller hockey (demonstration)

- Pavelló Olímpic de Badalona – basketball

- Sant Sadurní Cycling Circuit – cycling (individual road race)

- Some events, including diving, took place in view of construction of the Sagrada Família

Medals awarded

The 1992 Summer Olympic programme featured 257 events in the following 25 sports:

|

|

|

|

Demonstration sports

Calendar

- All times are in Central European Summer Time (UTC+2)

| ● | Opening ceremony | Event competitions | ● | Event finals | ● | Closing ceremony |

| Date | July | August | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24th Fri | 25th Sat | 26th Sun | 27th Mon | 28th Tue | 29th Wed | 30th Thu | 31st Fri | 1st Sat | 2nd Sun | 3rd Mon | 4th Tue | 5th Wed | 6th Thu | 7th Fri | 8th Sat | 9th Sun | |

| Archery | ● | ● | ● ● | ||||||||||||||

| Athletics | ● ● | ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● |

● | ||||||||

| Badminton | ● ● ● ● |

||||||||||||||||

| Baseball | ● | ||||||||||||||||

| Basketball | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Boxing | ● ● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● ● | |||||||||||||||

| Canoeing | ● ● | ● ● | ● ● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● ● |

|||||||||||||

| Cycling | ● ● | ● | ● | ● ● ● ● ● |

● | ||||||||||||

| Diving | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||

| Equestrian | ● ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||

| Fencing | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||

| Field hockey | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Football | ● | ||||||||||||||||

| Gymnastics | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● ● |

● | ||||||||||

| Handball | ● ● | ||||||||||||||||

| Judo | ● ● | ● ● | ● ● | ● ● | ● ● | ● ● | ● ● | ||||||||||

| Modern pentathlon | ● ● | ||||||||||||||||

| Rowing | ● ● ● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● ● |

|||||||||||||||

| Sailing | ● ● | ● ● ● ● ● ● ● |

● | ||||||||||||||

| Shooting | ● ● | ● ● | ● ● | ● | ● ● | ● ● | ● | ● | |||||||||

| Swimming | ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● ● |

|||||||||||

| Synchronized swimming | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Table tennis | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||

| Tennis | ● ● | ● ● | |||||||||||||||

| Volleyball | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Water polo | ● | ||||||||||||||||

| Weightlifting | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● ● | ● | ||||||||

| Wrestling | ● ● ● |

● ● ● |

● ● ● ● |

● ● ● |

● ● ● |

● ● ● ● |

|||||||||||

| Total gold medals | 9 | 12 | 14 | 17 | 19 | 19 | 22 | 30 | 18 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 22 | 30 | 10 | ||

| Ceremonies | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Date | 24th Fri | 25th Sat | 26th Sun | 27th Mon | 28th Tue | 29th Wed | 30th Thu | 31st Fri | 1st Sat | 2nd Sun | 3rd Mon | 4th Tue | 5th Wed | 6th Thu | 7th Fri | 8th Sat | 9th Sun |

| July | August | ||||||||||||||||

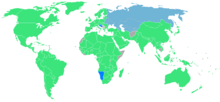

Participating National Olympic Committees

A total of 169 nations sent athletes to compete in the 1992 Summer Games.

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, twelve of the fifteen new states chose to form a Unified Team, while the Baltic States of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania each entered their own teams for the first time since 1936. For the first time, Croatia, Slovenia and Bosnia-Herzegovina competed as independent nations after their separation from Socialist Yugoslavia, and Namibia and the unified team of Yemen (previously North and South Yemen) also made their Olympic debuts.

The 1992 Summer Olympics notably marked Germany competing as a unified team for the first time since 1964, while South Africa returned to the Games for the first time in 32 years.

The Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was banned due to UN sanctions, but individual Yugoslav athletes were allowed to take part as Independent Olympic Participants. Four National Olympic Committees did not send any athletes to compete: Afghanistan, Brunei, Liberia and Somalia.

.svg.png)

Medal count

The following table reflects the top ten nations in terms of total medals won at the 1992 Games (the host nation is highlighted).

| Rank | Nation | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45 | 38 | 29 | 112 | |

| 2 | 37 | 34 | 37 | 108 | |

| 3 | 33 | 21 | 28 | 82 | |

| 4 | 16 | 22 | 16 | 54 | |

| 5 | 14 | 6 | 11 | 31 | |

| 6 | 13 | 7 | 2 | 22 | |

| 7 | 12 | 5 | 12 | 29 | |

| 8 | 11 | 12 | 7 | 30 | |

| 9 | 8 | 5 | 16 | 29 | |

| 10 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 27 | |

| Totals (10 nations) | 196 | 159 | 169 | 524 | |

Broadcast rights

The 1992 Summer Olympics were covered by the following television and radio broadcasters:[20]

Terrorism

The Basque nationalist group ETA attempted to disrupt the Barcelona Games with terrorist attacks. It was already feared beforehand that ETA would use the Olympics to gain publicity for their cause in front of a worldwide audience.[21] As the time of the Games approached,[22] ETA committed attacks in Barcelona and the Catalonia region as a whole, including the deadly 1991 Vic bombing.[23][24] On 10 July 1992, the group offered a two-month truce covering the Olympics in exchange for negotiations, which the Spanish government rejected.[25] However, the Games went ahead successfully without an attack.[26]

Effect on the city

The celebration of the 1992 Olympic Games had an enormous impact on the urban culture and outward projection of Barcelona. The Games provided billions of dollars for infrastructure investments, which are considered to have improved the quality of life in the city, and its attraction for investment and tourism.[27] Barcelona became one of the most visited cities in Europe after Paris, London, and Rome.[28][29]

Barcelona's nomination for the 1992 Summer Olympics sparked the implementation of an ambitious plan for urban transformation that had already been developed previously.[30] Barcelona was opened to the sea with the construction of the Olympic Village and Olympic Port in Poblenou. New centres were created, and modern sports facilities were built in the Olympic zones of Montjuïc, Diagonal, and Vall d'Hebron; hotels were also refurbished and new ones built. The construction of ring roads around the city helped to reduce traffic density, and El Prat airport was modernized and expanded with the opening of two new terminals.[31]

Cost and cost overrun

The Oxford Olympics Study[32] estimates the direct costs of the Barcelona 1992 Summer Olympics to be US$9.7 billion (expressed in 2015 U.S. dollars) with a cost overrun of 266%. This includes only sports-related costs, that is: (i) operational costs incurred by the organizing committee for the purpose of staging the Games, e.g., expenditures for technology, direct transportation, workforce, administration, security, catering, ceremonies, and medical services; and (ii) direct capital costs incurred by the host city and country or private investors to build the competition venues, the Olympic village, international broadcast center, media and press center, and similar structures required to host the Games. Costs excluded from the study are indirect capital and infrastructure costs, such as for road, rail, or airport infrastructure, or for hotel upgrades or other business investment incurred in preparation for the Games.[32][33]

The costs for Barcelona 1992 may be compared with those of London 2012, which cost US$15 billion with a cost overrun of 76%, and those of Rio 2016 which cost US$4.6 billion with a cost overrun of 51%. The average cost for the Summer Olympics since 1960 is US$5.2 billion, with an average cost overrun of 176%.[32][33]

Songs and themes

There were two main musical themes for the 1992 Games. The first one was "Barcelona", a classical crossover song composed five years earlier by Freddie Mercury and Mike Moran; Mercury was an admirer of lyric soprano Montserrat Caballé, both recorded the official theme as a duet. Due to Mercury's death eight months earlier, the duo was unable to perform the song together during the opening ceremony. A recording of the song instead played over a travelogue of the city at the start of the opening ceremony, seconds before the official countdown.[34][35] "Amigos Para Siempre" (Friends for Life) was the other musical theme. It was written by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Don Black, and sung by Sarah Brightman and José Carreras during the closing ceremonies.

Ryuichi Sakamoto composed and conducted the opening ceremony musical score.[36] The Opening Olympic fanfare was composed by Angelo Badalamenti and with orchestrations by Joseph Turrin.

Mascot

The official mascot was Cobi, a Catalan sheepdog in cubist style designed by Javier Mariscal.[37]

Corporate image and identity

A renewal in Barcelona's image and corporate identity could be seen in the publication of posters, commemorative coins, stamps minted by the FNMT in Madrid, and the Barcelona 1992 Olympic Official Commemorative Medals, designed and struck in Barcelona.

See also

- Summer Olympic Games

- Olympic Games

- International Olympic Committee

- List of IOC country codes

- Olympics Triplecast

- Use of performance-enhancing drugs at the 1992 Olympic Games

- Barcelona Gold – compilation album released for the 1992 Games

References

- "Factsheet - Opening Ceremony of the Games of the Olympiad" (PDF) (Press release). International Olympic Committee. 9 October 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 August 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- "Albertville 1992". www.olympic.org. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- "Barcelona 1992 Summer Olympics | Olympic Videos, Photos, News". Olympic.org. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- "IOC Vote History". Aldaver.com. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- Miller, Judith (18 October 1986). "Barcelona gets 1992 Summer Olympics" (Archives). The New York Times.

- "Past Olympic Host City Election Results". Archived from the original on 30 June 2011.

- "Ciudad Olímpica: La parábola del suspiro" [Olympic City: The parable of the sigh]. La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 27 July 1992. p. 36.

- "Ceremonial hall of shame". BBC News. 15 September 2000. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- "Official Report of the Games of the XXV Olympiad, Barcelona 1992, v.4". LA84 Foundation. 1992. p. 72. ISBN 84-7868-097-7.

The arrow described an arc and lit the gas issuing from the cauldron; the flame soared up to a height of three metres.

- "Barcelona 1992: Did you know?". IOC. 2002. Archived from the original on 4 April 2002.

- "Hall of Famers: 1992 United States Olympic Team". Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- "Fermin Cacho Ruiz". Olympic.org. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- Arnold, Chloe (11 February 2012). "Hassiba Boulmerka: Defying death threats to win gold". Algiers: BBC News.

- Farber, Michael (30 July 1996). "On the Bright Side". CNN/SI. Archived from the original on 16 September 2000.

- 1992 Olympics Official Report. Part IV (PDF). Retrieved 24 October 2012.

List of participants by NOC's and sport.

- Barcelona 1992 Opening Ceremony Parade of Nations 2/8 on YouTube

- Barcelona 1992 Opening Ceremony Parade of Nations 1/8 on YouTube

- Barcelona 1992 Opening Ceremony Parade of Nations 4/8 on YouTube

- Barcelona 1992 Opening Ceremony Parade of Nations 6/8 on YouTube

- Miquel de Moragas, Nancy Kay Rivenburgh, ed. (1995). Television in the Olympics : international research project (illustrated ed.). James F. Larson. pp. 257–260. ISBN 978-0861965380. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- Fussey, Pete; Coaffee, Jon; Hobbs, Dick (April 2011). Securing and Sustaining the Olympic City: Reconfiguring London for 2012 and Beyond. Routledge. p. 48. ISBN 9780754679455.

- "CTV News - CTV News Channel". www.ctvnews.ca. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- "Spain Tackles Terrorist Threat By Basques to Olympics, Expo". 1 April 1992. Retrieved 17 January 2019 – via Christian Science Monitor.

- Finkelstein, Beth; Koch, Noel (11 August 1991). "The Threat to the Games in Spain". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018.

- "Eta rebuffed". The Independent. 13 July 1992. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- Thompson, Wayne C (31 August 2017). Western Europe 2017-2018. ISBN 9781475835090.

- Brunet, Ferran (2005). "The economic impact of the Barcelona Olympic Games, 1986–2004" (PDF). Autonomous University of Barcelona. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2009.

- Payne, Bob (6 August 2008). "The Olympics Effect". MSNBC. Archived from the original on 2 September 2008.

- Bremner, Caroline (11 October 2007). "Top 150 City Destinations: London Leads the Way". Euromonitor International. Archived from the original on 4 September 2009.

- Brunet, Ferran (1995). "An economic analysis of the Barcelona '92 Olympic Games: resources, financing, and impact" (PDF). Autonomous University of Barcelona. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 September 2017.

- Beard, Matthew (22 March 2011). "Lessons of Barcelona: 1992 Games provided model for London... and few warnings". London Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- Flyvbjerg, Bent; Stewart, Allison; Budzier, Alexander (2016). The Oxford Olympics Study 2016: Cost and Cost Overrun at the Games. Oxford: Saïd Business School Working Papers (Oxford: University of Oxford). pp. 18–20. SSRN 2804554.

- Joe Myers (29 July 2016). "The cost of hosting every Olympics since 1964" (Based on working paper from The University of Oxford and Said Business School). World Economic Forum.

- "Barcelona 92: 11 momentos inolvidables de aquellos Juegos Olímpicos (VÍDEOS, FOTOS)" (in Spanish). The Huffington Post. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- "Barcelona 92: inicio de la ceremonia". YouTube. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- Illness, Critical (3 September 2010). "Doreen D'Agostino Media " Ryuichi Sakamoto and Decca". Doreendagostinomedia.com. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- "Barcelona 1992 - Summer Games Mascots". Olympic.org. IOC. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1992 Summer Olympics. |

| External video | |

|---|---|

- "Barcelona 1992". Olympic.org. International Olympic Committee.

- "Results and Medalists—1992 Summer Olympics". Olympic.org. International Olympic Committee.

- Barcelona Olympic Foundation

- Olympic Review 1992 - Official results

- Barcelona Olympic Stadium

- Postage stamps of the Republic of Moldova, celebrating the Barcelona Summer Olympics in 1992

- Postage stamps of the Republic of Moldova, celebrating medal winners at the Barcelona Summer Olympics in 1992

| Preceded by Seoul |

Summer Olympic Games Barcelona XXV Olympiad (1992) |

Succeeded by Atlanta |