Sagrada Família

The Basílica de la Sagrada Família (Catalan: [bəˈzilikə ðə lə səˈɣɾaðə fəˈmiljə]; Spanish: Basílica de la Sagrada Familia; 'Basilica of the Holy Family'),[4] also known as the Sagrada Família, is a large unfinished Roman Catholic minor basilica in the Eixample district of Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain. Designed by Spanish/Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí (1852–1926), his work on the building is part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[5] On 7 November 2010, Pope Benedict XVI consecrated the church and proclaimed it a minor basilica.[6][7][8]

| Basílica de la Sagrada Família | |

|---|---|

Basílica de la Sagrada Família | |

Nativity façade in August 2017 | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic |

| District | Barcelona |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Minor basilica |

| Leadership | Juan José Cardinal Omella, Archbishop of Barcelona |

| Year consecrated | 7 November 2010 by Benedict XVI |

| Status | Active/under construction |

| Location | |

| Location | Barcelona, Spain |

| Geographic coordinates | 41°24′13″N 2°10′28″E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Antoni Gaudí |

| Style | Gothic and Modernisme |

| General contractor | Construction Board of La Sagrada Família Foundation[1] |

| Groundbreaking | 19 March 1882 |

| Completed | 2026 (planned)[2] |

| Specifications | |

| Direction of façade | Southeast |

| Capacity | 9,000 |

| Length | 90 m (300 ft)[3] |

| Width | 60 m (200 ft)[3] |

| Width (nave) | 45 m (150 ft)[3] |

| Spire(s) | 18 (8 already built) |

| Spire height | 170 m (560 ft) (planned) |

| Website | |

| sagradafamilia | |

| Part of | Works of Antoni Gaudí |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iv |

| Reference | 320-005 |

| Inscription | 2005 (29th session) |

On 19 March 1882, construction of the Sagrada Família began under architect Francisco de Paula del Villar. In 1883, when Villar resigned,[5] Gaudí took over as chief architect, transforming the project with his architectural and engineering style, combining Gothic and curvilinear Art Nouveau forms. Gaudí devoted the remainder of his life to the project, and he is buried in the crypt. At the time of his death in 1926, less than a quarter of the project was complete.[9]

Relying solely on private donations, the Sagrada Família's construction progressed slowly and was interrupted by the Spanish Civil War. In July 1936, revolutionaries set fire to the crypt and broke their way into the workshop, partially destroying Gaudí's original plans, drawings and plaster models, which led to 16 years of work to piece together the fragments of the master model.[10] Construction resumed to intermittent progress in the 1950s. Advancements in technologies such as computer aided design and computerised numerical control (CNC) have since enabled faster progress and construction passed the midpoint in 2010. However, some of the project's greatest challenges remain, including the construction of ten more spires, each symbolising an important Biblical figure in the New Testament.[9] It is anticipated that the building can be completed by 2026, the centenary of Gaudí's death.[11]

The basilica has a long history of splitting opinion among the residents of Barcelona: over the initial possibility it might compete with Barcelona's cathedral, over Gaudí's design itself, over the possibility that work after Gaudí's death disregarded his design,[12] and the 2007 proposal to build a tunnel of Spain's high-speed rail link to France which could disturb its stability.[13] Describing the Sagrada Família, art critic Rainer Zerbst said "it is probably impossible to find a church building anything like it in the entire history of art",[14] and Paul Goldberger describes it as "the most extraordinary personal interpretation of Gothic architecture since the Middle Ages".[15] The basilica is not the cathedral church of the Archdiocese of Barcelona, as that title belongs to the Cathedral of the Holy Cross and Saint Eulalia.

History

Background

.jpg)

The Basílica de la Sagrada Família was the inspiration of a bookseller, Josep Maria Bocabella, founder of Asociación Espiritual de Devotos de San José (Spiritual Association of Devotees of St. Joseph).[16]

After a visit to the Vatican in 1872, Bocabella returned from Italy with the intention of building a church inspired by the basilica at Loreto.[16] The apse crypt of the church, funded by donations, was begun 19 March 1882, on the festival of St. Joseph, to the design of the architect Francisco de Paula del Villar, whose plan was for a Gothic revival church of a standard form.[16] The apse crypt was completed before Villar's resignation on 18 March 1883, when Antoni Gaudí assumed responsibility for its design, which he changed radically.[16] Gaudi began work on the church in 1883 but was not appointed Architect Director until 1884.

Construction

On the subject of the extremely long construction period, Gaudí is said to have remarked: "My client is not in a hurry."[17] When Gaudí died in 1926, the basilica was between 15 and 25 percent complete.[9][18] After Gaudí's death, work continued under the direction of Domènec Sugrañes i Gras until interrupted by the Spanish Civil War in 1936.

Parts of the unfinished basilica and Gaudí's models and workshop were destroyed during the war by Catalan anarchists. The present design is based on reconstructed versions of the plans that were burned in a fire as well as on modern adaptations. Since 1940, the architects Francesc Quintana, Isidre Puig Boada, Lluís Bonet i Gari and Francesc Cardoner have carried on the work. The illumination was designed by Carles Buïgas. The current director and son of Lluís Bonet, Jordi Bonet i Armengol, has been introducing computers into the design and construction process since the 1980s. Mark Burry of New Zealand serves as Executive Architect and Researcher.[19] Sculptures by J. Busquets, Etsuro Sotoo and the controversial Josep Maria Subirachs decorate the fantastical façades. Barcelona-born Jordi Fauli took over as chief architect in 2012.[20]

The central nave vaulting was completed in 2000 and the main tasks since then have been the construction of the transept vaults and apse. As of 2006, work concentrated on the crossing and supporting structure for the main steeple of Jesus Christ as well as the southern enclosure of the central nave, which will become the Glory façade.

The church shares its site with the Sagrada Família Schools building, a school originally designed by Gaudí in 1909 for the children of the construction workers. Relocated in 2002 from the eastern corner of the site to the southern corner, the building now houses an exhibition.

- Historical photographs of the Sagrada Família

1905

1905 1915

1915 1930. Aerial photograph by Walter Mittelholzer, ETH-Bibliothek.

1930. Aerial photograph by Walter Mittelholzer, ETH-Bibliothek.

Construction status

Chief architect Jordi Fauli announced in October 2015 that construction is 70 percent complete and has entered its final phase of raising six immense steeples. The steeples and most of the church's structure are to be completed by 2026, the centennial of Gaudí's death; as of a 2017 estimate, decorative elements should be complete by 2030 or 2032.[21] Visitor entrance fees of €15 to €20 finance the annual construction budget of €25 million.[22] Computer-aided design technology has been used to accelerate construction of the building. Current technology allows stone to be shaped off-site by a CNC milling machine, whereas in the 20th century the stone was carved by hand.[23]

In 2008, some renowned Catalan architects advocated halting construction[24] to respect Gaudí's original designs, which although they were not exhaustive and were partially destroyed, have been partially reconstructed in recent years.[25]

In 2018, the stone type needed for the construction was found in a quarry in Brinscall, near Chorley, England.[26]

Recent history

AVE tunnel

Since 2013, AVE high-speed trains have passed near the Sagrada Família through a tunnel that runs beneath the centre of Barcelona. The tunnel's construction, which began on 26 March 2010, was controversial. The Ministry of Public Works of Spain (Ministerio de Fomento) claimed the project posed no risk to the church.[27][28] Sagrada Família engineers and architects disagreed, saying there was no guarantee that the tunnel would not affect the stability of the building. The Board of the Sagrada Família (Patronat de la Sagrada Família) and the neighborhood association AVE pel Litoral (AVE by the Coast) had led a campaign against this route for the AVE, without success.

In October 2010, the tunnel boring machine reached the church underground under the location of the building's principal façade.[27] Service through the tunnel was inaugurated on 8 January 2013.[29] Track in the tunnel makes use of a system by Edilon Sedra in which the rails are embedded in an elastic material to dampen vibrations.[30] No damage to the Sagrada Família has been reported to date.

Consecration

The main nave was covered and an organ installed in mid-2010, allowing the still-unfinished building to be used for religious services.[31] The church was consecrated by Pope Benedict XVI on 7 November 2010 in front of a congregation of 6,500 people.[32] A further 50,000 people followed the consecration Mass from outside the basilica, where more than 100 bishops and 300 priests were on hand to offer Holy Communion.[33]

Starting on 9 July 2017, there is an international mass celebrated at the basilica on every Sunday and holy day of obligation, at 9 a.m, open to the public (until the church is full). Occasionally, Mass is celebrated at other times, where attendance requires an invitation. When masses are scheduled, instructions to obtain an invitation are posted on the basilica's website. In addition, visitors may pray in the chapel of the Blessed Sacrament and Penitence.[34]

Fire

On 19 April 2011, an arsonist started a small fire in the sacristy which forced the evacuation of tourists and construction workers.[35] The sacristy was damaged, and the fire took 45 minutes to contain.[36]

Pandemic

On 11 March 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain, construction was stopped and the basilica was closed.[37] This is the first time the construction has been halted since the Spanish Civil War.[38] The Gaudí House Museum in Park Güell was also closed. The basilica reopened, initially to key workers on 4 July 2020.[39]

Design

The style of la Sagrada Família is variously likened to Spanish Late Gothic, Catalan Modernism or Art Nouveau. While the Sagrada Família falls within the Art Nouveau period, Nikolaus Pevsner points out that, along with Charles Rennie Mackintosh in Glasgow, Gaudí carried the Art Nouveau style far beyond its usual application as a surface decoration.[40]

Plan

While never intended to be a cathedral, the Sagrada Família was planned from the outset to be a cathedral-sized building. Its ground-plan has obvious links to earlier Spanish cathedrals such as Burgos Cathedral, León Cathedral and Seville Cathedral. In common with Catalan and many other European Gothic cathedrals, the Sagrada Família is short in comparison to its width, and has a great complexity of parts, which include double aisles, an ambulatory with a chevet of seven apsidal chapels, a multitude of steeples and three portals, each widely different in structure as well as ornament. Where it is common for cathedrals in Spain to be surrounded by numerous chapels and ecclesiastical buildings, the plan of this church has an unusual feature: a covered passage or cloister which forms a rectangle enclosing the church and passing through the narthex of each of its three portals. With this peculiarity aside, the plan, influenced by Villar's crypt, barely hints at the complexity of Gaudí's design or its deviations from traditional church architecture. There are no exact right angles to be seen inside or outside the church, and few straight lines in the design.[41][42]

Spires

Gaudí's original design calls for a total of eighteen spires, representing in ascending order of height the Twelve Apostles,[43] the Virgin Mary, the four Evangelists and, tallest of all, Jesus Christ. Eight spires have been built as of 2010, corresponding to four apostles at the Nativity façade and four apostles at the Passion façade.

According to the 2005 "Works Report" of the project's official website, drawings signed by Gaudí and recently found in the Municipal Archives, indicate that the spire of the Virgin was in fact intended by Gaudí to be shorter than those of the evangelists. The spire height will follow Gaudí's intention, which according to the report will work with the existing foundation.

The Evangelists' spires will be surmounted by sculptures of their traditional symbols: a winged bull (Saint Luke), a winged man (Saint Matthew), an eagle (Saint John), and a winged lion (Saint Mark). The central spire of Jesus Christ is to be surmounted by a giant cross; its total height (172.5 metres (566 ft)) will be less than that of Montjuïc hill in Barcelona,[44] as Gaudí believed that his creation should not surpass God's. The lower spires are surmounted by communion hosts with sheaves of wheat and chalices with bunches of grapes, representing the Eucharist. Plans call for tubular bells to be placed within the spires, driven by the force of the wind, and driving sound down into the interior of the church. Gaudí performed acoustic studies to achieve the appropriate acoustic results inside the temple.[45] However, only one bell is currently in place.[46]

The completion of the spires will make Sagrada Família the tallest church building in the world.

Façades

The Church will have three grand façades: the Nativity façade to the East, the Passion façade to the West, and the Glory façade to the South (yet to be completed). The Nativity Façade was built before work was interrupted in 1935 and bears the most direct Gaudí influence. The Passion façade was built according to the design that Gaudi created in 1917. The construction began in 1954, and the steeples, built over the elliptical plan, were finished in 1976. It is especially striking for its spare, gaunt, tormented characters, including emaciated figures of Christ being scourged at the pillar; and Christ on the Cross. These controversial designs are the work of Josep Maria Subirachs. The Glory façade, on which construction began in 2002, will be the largest and most monumental of the three and will represent one's ascension to God. It will also depict various scenes such as Hell, Purgatory, and will include elements such as the Seven deadly sins and the Seven heavenly virtues.

Nativity Façade

Constructed between 1894 and 1930, the Nativity façade was the first façade to be completed. Dedicated to the birth of Jesus, it is decorated with scenes reminiscent of elements of life. Characteristic of Gaudí's naturalistic style, the sculptures are ornately arranged and decorated with scenes and images from nature, each a symbol in its own manner. For instance, the three porticos are separated by two large columns, and at the base of each lies a turtle or a tortoise (one to represent the land and the other the sea; each are symbols of time as something set in stone and unchangeable). In contrast to the figures of turtles and their symbolism, two chameleons can be found at either side of the façade, and are symbolic of change.

The façade faces the rising sun to the northeast, a symbol for the birth of Christ. It is divided into three porticos, each of which represents a theological virtue (Hope, Faith and Charity). The Tree of Life rises above the door of Jesus in the portico of Charity. Four steeples complete the façade and are each dedicated to a Saint (Matthias, Barnabas, Jude the Apostle, and Simon the Zealot).

Originally, Gaudí intended for this façade to be polychromed, for each archivolt to be painted with a wide array of colours. He wanted every statue and figure to be painted. In this way the figures of humans would appear as much alive as the figures of plants and animals.[47]

Gaudí chose this façade to embody the structure and decoration of the whole church. He was well aware that he would not finish the church and that he would need to set an artistic and architectural example for others to follow. He also chose for this façade to be the first on which to begin construction and for it to be, in his opinion, the most attractive and accessible to the public. He believed that if he had begun construction with the Passion Façade, one that would be hard and bare (as if made of bones), before the Nativity Façade, people would have withdrawn at the sight of it.[48] Some of the statues were destroyed in 1936 during the Spanish Civil War, and subsequently were reconstructed by the Japanese artist Etsuro Sotoo.[49]

Passion Façade

In contrast to the highly decorated Nativity Façade, the Passion Façade is austere, plain and simple, with ample bare stone, and is carved with harsh straight lines to resemble the bones of a skeleton. Dedicated to the Passion of Christ, the suffering of Jesus during his crucifixion, the façade was intended to portray the sins of man. Construction began in 1954, following the drawings and instructions left by Gaudí for future architects and sculptors. The steeples were completed in 1976, and in 1987 a team of sculptors, headed by Josep Maria Subirachs, began work sculpting the various scenes and details of the façade. They aimed to give a rigid, angular form to provoke a dramatic effect. Gaudí intended for this façade to strike fear into the onlooker. He wanted to "break" arcs and "cut" columns, and to use the effect of chiaroscuro (dark angular shadows contrasted by harsh rigid light) to further show the severity and brutality of Christ's sacrifice.

Facing the setting sun, indicative and symbolic of the death of Christ, the Passion Façade is supported by six large and inclined columns, designed to resemble Sequoia trunks. Above there is a pyramidal pediment, made up of eighteen bone-shaped columns, which culminate in a large cross with a crown of thorns. Each of the four steeples is dedicated to an apostle (James, Thomas, Philip, and Bartholomew) and, like the Nativity Façade, there are three porticos, each representing the theological virtues, though in a much different light.

The scenes sculpted into the façade may be divided into three levels, which ascend in an S form and reproduce the stations of the Cross (Via Crucis of Christ).[3] The lowest level depicts scenes from Jesus' last night before the crucifixion, including the Last Supper, Kiss of Judas, Ecce homo, and the Sanhedrin trial of Jesus. The middle level portrays the Calvary, or Golgotha, of Christ, and includes The Three Marys, Saint Longinus, Saint Veronica, and a hollow-face illusion of Christ on the Veil of Veronica. In the third and final level the Death, Burial and the Resurrection of Christ can be seen. A bronze figure situated on a bridge creating a link between the steeples of Saint Bartholomew and Saint Thomas represents the Ascension of Jesus.[50]

The façade contains a magic square based on[51] the magic square in the 1514 print Melencolia I. The square is rotated and one number in each row and column is reduced by one so the rows and columns add up to 33 instead of the standard 34 for a 4x4 magic square.

Glory Façade

Model of the completed Temple; the Glory Façade is on the foreground.

Model of the completed Temple; the Glory Façade is on the foreground. Model showing the entrance as wished by Gaudí.

Model showing the entrance as wished by Gaudí. Ground model, showing Carrer de Mallorca running underground.

Ground model, showing Carrer de Mallorca running underground. Glory Façade under construction (in 2016).

Glory Façade under construction (in 2016). The Glory Façade from inside.

The Glory Façade from inside.

The largest and most striking of the façades will be the Glory Façade, on which construction began in 2002. It will be the principal façade and will offer access to the central nave. Dedicated to the Celestial Glory of Jesus, it represents the road to God: Death, Final Judgment, and Glory, while Hell is left for those who deviate from God's will. Aware that he would not live long enough to see this façade completed, Gaudí made a model which was demolished in 1936, whose original fragments were used as the basis for the development of the design for the façade. The completion of this façade may require the partial demolition of the block with buildings across the Carrer de Mallorca.[52]

To reach the Glory Portico the large staircase will lead over the underground passage built over Carrer de Mallorca with the decoration representing Hell and vice. On other projects Carrer de Mallorca will have to go underground.[53] It will be decorated with demons, idols, false gods, heresy and schisms, etc. Purgatory and death will also be depicted, the latter using tombs along the ground. The portico will have seven large columns dedicated to gifts of the Holy Spirit. At the base of the columns there will be representations of the Seven Deadly Sins, and at the top, The Seven Virtues.

- Gifts: wisdom, understanding, counsel, fortitude, knowledge, piety and fear of the Lord.

- Sins: greed, lust, pride, gluttony, sloth, wrath, envy.

- Virtues: kindness, diligence, patience, charity, temperance, humility, chastity.

This facade will have five doors corresponding to the five naves of the temple, with the central one having a triple entrance, that will give the Glory Façade a total seven doors representing the sacraments:

- Baptism

- Confirmation

- Eucharist

- Penance

- Holy orders

- Marriage

- Unction of the sick

In September 2008, the doors of the Glory façade, by Subirachs, were installed. Inscribed with the Lord's prayer, these central doors are inscribed with the words "Give us our daily bread" in fifty different languages. The handles of the door are the letters "A" and "G" that form the initials of Antoni Gaudí within the phrase "lead us not into temptation".

Interior

- Interior of the Sagrada Família

Standing in the transept and looking northeast (2011)

Standing in the transept and looking northeast (2011) Detail of the roof in the nave. Gaudí designed the columns to mirror trees and branches.[54]

Detail of the roof in the nave. Gaudí designed the columns to mirror trees and branches.[54]

.jpg)

The church plan is that of a Latin cross with five aisles. The central nave vaults reach forty-five metres (148 feet) while the side nave vaults reach thirty metres (98 feet). The transept has three aisles. The columns are on a 7.5 metre (25 ft) grid. However, the columns of the apse, resting on del Villar's foundation, do not adhere to the grid, requiring a section of columns of the ambulatory to transition to the grid thus creating a horseshoe pattern to the layout of those columns. The crossing rests on the four central columns of porphyry supporting a great hyperboloid surrounded by two rings of twelve hyperboloids (currently under construction). The central vault reaches sixty metres (200 feet). The apse is capped by a hyperboloid vault reaching seventy-five metres (246 feet). Gaudí intended that a visitor standing at the main entrance be able to see the vaults of the nave, crossing, and apse; thus the graduated increase in vault loft.

There are gaps in the floor of the apse, providing a view down into the crypt below.

The columns of the interior are a unique Gaudí design. Besides branching to support their load, their ever-changing surfaces are the result of the intersection of various geometric forms. The simplest example is that of a square base evolving into an octagon as the column rises, then a sixteen-sided form, and eventually to a circle. This effect is the result of a three-dimensional intersection of helicoidal columns (for example a square cross-section column twisting clockwise and a similar one twisting counter-clockwise).

Essentially none of the interior surfaces are flat; the ornamentation is comprehensive and rich, consisting in large part of abstract shapes which combine smooth curves and jagged points. Even detail-level work such as the iron railings for balconies and stairways are full of curvaceous elaboration.

Organ

In 2010 an organ was installed in the chancel by the Blancafort Orgueners de Montserrat organ builders. The instrument has 26 stops (1,492 pipes) on two manuals and a pedalboard.

To overcome the unique acoustical challenges posed by the church's architecture and vast size, several additional organs will be installed at various points within the building. These instruments will be playable separately (from their own individual consoles) and simultaneously (from a single mobile console), yielding an organ of some 8000 pipes when completed.[55]

Geometric details

The steeples on the Nativity façade are crowned with geometrically shaped tops that are reminiscent of Cubism (they were finished around 1930), and the intricate decoration is contemporary to the style of Art Nouveau, but Gaudí's unique style drew primarily from nature, not other artists or architects, and resists categorization.

Gaudí used hyperboloid structures in later designs of the Sagrada Família (more obviously after 1914). However, there are a few places on the nativity façade—a design not equated with Gaudí's ruled-surface design—where the hyperboloid crops up. For example, all around the scene with the pelican, there are numerous examples (including the basket held by one of the figures). There is a hyperboloid adding structural stability to the cypress tree (by connecting it to the bridge). And finally, the "bishop's mitre" spires are capped with hyperboloid structures.[56] In his later designs, ruled surfaces are prominent in the nave's vaults and windows and the surfaces of the Passion façade.

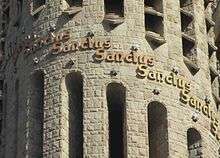

Symbolism

Themes throughout the decoration include words from the liturgy. The steeples are decorated with words such as "Hosanna", "Excelsis", and "Sanctus"; the great doors of the Passion façade reproduce excerpts of the Passion of Jesus from the New Testament in various languages, mainly Catalan; and the Glory façade is to be decorated with the words from the Apostles' Creed, while its main door reproduce the entire Lord's Prayer in Catalan, surrounded by multiple variations of "Give us this day our daily bread" in other languages. The three entrances symbolize the three virtues: Faith, Hope and Love. Each of them is also dedicated to a part of Christ's life. The Nativity Façade is dedicated to his birth; it also has a cypress tree which symbolizes the tree of life. The Glory façade is dedicated to his glory period. The Passion façade is symbolic of his suffering. The apse steeple bears Latin text of Hail Mary. All in all, the Sagrada Família is symbolic of the lifetime of Christ.

Areas of the sanctuary will be designated to represent various concepts, such as saints, virtues and sins, and secular concepts such as regions, presumably with decoration to match.

Burials

- Josep Maria Bocabella

- Antoni Gaudí

Appraisal

The art historian Nikolaus Pevsner, writing in the 1960s, referred to Gaudí's buildings as growing "like sugar loaves and anthills" and describes the ornamenting of buildings with shards of broken pottery as possibly "bad taste" but handled with vitality and "ruthless audacity".[40]

The building's design itself has been polarizing. Assessments by Gaudí's fellow architects were generally positive; Louis Sullivan greatly admired it, describing Sagrada Família as the "greatest piece of creative architecture in the last twenty-five years. It is spirit symbolised in stone!"[57] Walter Gropius praised the Sagrada Família, describing the building's walls as "a marvel of technical perfection".[57] Time magazine called it "sensual, spiritual, whimsical, exuberant",[17] However, author and critic George Orwell called it "one of the most hideous buildings in the world",[58] Author James A. Michener called it "one of the strangest-looking serious buildings in the world"[59] and British historian Gerald Brenan stated about the building "Not even in the European architecture of the period can one discover anything so vulgar or pretentious."[59] The building's distinctive silhouette has nevertheless become symbolic of Barcelona itself,[9] drawing an estimated 3 million visitors annually.[12]

World Heritage status

Together with six other Gaudí buildings in Barcelona, part of la Sagrada Família is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, as testifying "to Gaudí's exceptional creative contribution to the development of architecture and building technology", "having represented el Modernisme of Catalonia" and "anticipated and influenced many of the forms and techniques that were relevant to the development of modern construction in the 20th century". The inscription only includes the Crypt and the Nativity Façade.[5]

Visitor access

Visitors can access the Nave, Crypt, Museum, Shop, and the Passion and Nativity steeples. Entrance to either of the steeples requires a reservation and advance purchase of a ticket. Access is possible only by lift (elevator) and a short walk up the remainder of the steeples to the bridge between the steeples. Descent is via a very narrow spiral staircase of over 300 steps. There is a posted caution for those with medical conditions.[60]

As of June 2017, online ticket purchase has been available. As of August 2010, there had been a service whereby visitors could buy an entry code either at Servicaixa ATM kiosks (part of CaixaBank) or online.[61] During the peak season, May to October, reservation delays for entrance of up to a few days are not unusual.

International masses

The Archdiocese of Barcelona holds an international mass at the Basilica of the Sagrada Família every Sunday and on holy days of obligation.

- Date and time: Every Sunday and on holy days of obligation at 9 am

- There is no charge for attending mass but capacity is limited

- Visitors are asked to dress appropriately and behave respectfully.[62]

Funding and building permit

Construction on Sagrada Família is not supported by any government or official church sources. Private patrons funded the initial stages.[63] Money from tickets purchased by tourists is now used to pay for the work, and private donations are accepted through the Friends of the Sagrada Família.

The construction budget for 2009 was €18 million.[31]

In October 2018, Sagrada Família trustees agreed to pay €36 million in payments to the city authorities, to land a building permit after 136 years of construction.[64] Most of the funds would be directed to improve the access between the church and the Barcelona Metro.[65] The permit was issued by the city on 7 June 2019.[66]

See also

- List of basilicas

- List of Gaudí buildings

- List of Modernista buildings in Barcelona

- Sagrada Família metro station

References

- Fundació junta constructora del Temple Expiatori de la Sagrada Família Fundacions.cat

- Saldivia, Gabriela (9 June 2019). "Not Too Little, Too Late: Unfinished Gaudí Basilica Gets Permit 137 Years Later". NPR. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Gómez Gimeno, María José (2006). La Sagrada Família. Mundo Flip Ediciones. pp. 86–87. ISBN 84-933983-4-9.

- "Història de la Basilica, 1866–1883: Origens". Fundació Junta Constructora del Temple Expiatori de la Sagrada Família (in Catalan). Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- "Works of Antoni Gaudí". UNESCO.org. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- Drummer, Alexander (23 July 2010). "Pontiff to Proclaim Gaudí's Church a Basilica". ZENIT. Archived from the original on 25 September 2010. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- "The Pope Consecrates The Church of the Sagrada Familia". Vatican City: Vatican Information Service. 7 November 2010. Archived from the original on 4 August 2010. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- Delaney, Sarah (4 March 2010). "Pope to visit Santiago de Compostela, Barcelona in November". Catholic News Service. Archived from the original on 7 April 2010. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- Minder, Raphael (3 November 2010). "Polishing Gaudí's Unfinished Jewel". The New York Times.

- Fraser, Giles (3 June 2015). "Barcelona's Sagrada Família: Gaudí's 'cathedral for the poor' – a history of cities in 50 buildings, day 49". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- "Video: See How La Sagrada Família Will Progress in 2015", metropolismag.com, 25 September 2014 (retrieved 2 October 2019)

- Schumacher, Edward (1 January 1991). "Gaudí's Church Still Divides Barcelona". The New York Times.

- Burnett, Victoria (11 June 2007). "Warning: Trains Coming. A Masterpiece Is at Risk". The New York Times.

- Rainer Zerbst, Gaudí – a Life Devoted to Architecture., pp. 190–215

- Goldberger, Paul (28 January 1991). "Barcelona". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 7 February 2010.

- "Sagrada Família". gaudiclub.com. The Gaudí & Barcelona Club.

- Hornblower, Margo (28 January 1991). "Heresy Or Homage in Barcelona?". Time.

- Gladstone, Valerie (22 August 2004). "ARCHITECTURE: Gaudí's Unfinished Masterpiece Is Virtually Complete". The New York Times.

- Fitzpatrick, Lisa (28 September 2011). "The Gaudí code". Barcelona Metropolitan. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- "A Completion Date for Sagrada Família, Helped by Technology". ArchitectMagazine.com. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- Cunningham, Sharon (30 October 2017). "What are the main milestones for the Sagrada Família in the future?". Blog Sagrada Família.

- Wilson, Joseph. "Barcelona's La Sagrada Familia Basilica enters final years of construction". Toronto Sun. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- Daniel, Paul. "Diamond tools help shape the Sagrada Família". Industrial Diamond Review. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- Fancelli, Agustí (4 December 2008). "¿Por qué no parar la Sagrada Familia?" [Why not stop the Sagrada Familia?] (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 July 2010. (English tr.)

- Burry, Mark; Gaudí, Antoni (2007). Gaudí Unseen. Berlin: Jovis Verlag. ISBN 978-3-939633-78-5.

- Titley, Megan (2 May 2018). "Barcelona's iconic Basilica de la Sagrada Familia built with stone from Lancashire". Lancashire Post. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Comorera, Ramon (13 October 2010). "La tuneladora del AVE perfora ya a cuatro metros de la Sagrada Família" [The tunnel boring machine of the AVE is already excavating four meters from the Sagrada Família]. El Periódico de Catalunya (in Spanish). Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ADIF (Administrator of Railway Infrastructures). "Madrid – Zaragoza Barcelona – French Border Line Barcelona Sants-Sagrera – high-speed tunnel". Archived from the original on 21 June 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- "El AVE alcanza Girona". El Periódico de Catalunya (in Spanish). 8 January 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- Comorera, Ramon (12 March 2012). "Doble aislante de vibraciones en las obras de Gaudí" [Double Isolation of Vibrations at the Gaudí constructions]. El Periódico de Catalunya (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- Montañés, José Ángel (13 March 2009). "La Sagrada Familia se abrirá al culto en septiembre de 2010". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 June 2009. (English tr)

- "Pope Benedict consecrates Barcelona's Sagrada Familia". BBC News. 7 November 2010.

- "Visita histórica del Papa a Barcelona para dedicar la Sagrada Família". La Vanguardia. 7 November 2010.

- "Worship at the Basilica". Sagrada Família. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- Woolls, Daniel (19 April 2011). "Fire in Barcelona church sees tourists evacuated". The Star. Toronto.

- "Fire by suspected arsonist at Sagrada Familia". The Telegraph. 19 April 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- "Junta agrees to stop works and visits to the Basilica". Sagrada Família. 11 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- "Spain's La Sagrada Familia will not restart construction works until after visitors return". The Olive Press. 4 May 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- "Coronavirus: Barcelona's Sagrada Familia basilica reopens to key workers". BBC. 4 July 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- Nikolaus Pevsner, An Outline of European Architecture, Penguin Books, (1963), pp. 394–5

- Strickland, Carol; Handy, Amy (11 April 2001). The Annotated Arch: A Crash Course in the History of Architecture. 2. Andrews McMeel Publishing. p. 112. ISBN 9780740710247. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- Gaudí, Antoni; Cuito, Aurora; Montes, Cristina (2002). Gaudí. A. Asppan S.L. p. 136. ISBN 9788489439917. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- Note: the two Apostles who are also Evangelists are left out and replaced by St. Paul and also St. Barnabas.

- "The Sagrada Família: a Temple where verticality rules". Blog Sagrada Família. 10 July 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- Álvaro Muñoz, Mari Carmen; Llop i Bayo, Francesc. "Tubular bell". Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- "Inventario de campanas de las Catedrales de España". Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- Bergós i Massó, Joan (1999). Gaudí, l'home i l'obra. Barcelona: Ed. Lunwerg. p. 40. ISBN 84-7782-617-X.

- Barral i Altet, Xavier (1999). Art de Catalunya. Arquitectura religiosa moderna i contemporània. Barcelona: L'isard. p. 218. ISBN 84-89931-14-3.

- Sendra, Enric (17 July 2014). "First door of the Nativity Façade of the Sagrada Família has now been fitted". Catalan News. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- "La Sagrada Familia abrirá al culto en 2008, según sus responsables" [The Sagrada Familia opens for worship in 2008, according to its leaders]. El Mundo (in Spanish). Mundinteractivos, SA. Europa Press. 2 June 2005. Retrieved 7 July 2010. (English tr.)

- "The magic square on the Passion façade: keys to understanding it". Blog Sagrada Família. 7 February 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- "The Future of La Sagrada Família - Urban Plans With 2026 In Mind". Barcelonas.

- Lover, Art Nouveau (28 March 2019). "Sagrada Familia – The Glory Facade". GaudiAllGaudi.com.

- Zerb, p.30

- Blancafort Orgueners de Montserrat, Archived 3 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in Catalan)

- Burry, M. C.; Burry, J. R.; Dunlop, G. M.; Maher, A. (2001). "Drawing Together Euclidean and Topological Threads" (PDF). The 13th Annual Colloquium of the Spatial Information Research Centre, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 5 August 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) The paper explores the assemblies of second order hyperbolic surfaces as they are used throughout the design composition of the Sagrada Família Church building. - Mower, David (1977). Gaudí. Oresko Books Limited. p. 6. ISBN 0905368096.

- Orwell, George (1938). Homage to Catalonia. Secker and Warburg.

[the anarchists] showed bad taste in not blowing it up when they had the chance.

- Delaney, Paul (24 October 1987). "Gaudí's Cathedral: And Now?". The New York Times.

- https://sagradafamilia.org/en/avis-legal Legal Disclaimer

- "Tickets". Basílica de la Sagrada Família. Archived from the original on 8 June 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- "sagradafamilia.org".

- Fletcher, Tom. "Sagrada Família Church of the Holy Family". Essential Architecture. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- "136 years late, La Sagrada Familia finally lands a building permit". New Atlas. 24 October 2018.

- "Barcelona's Sagrada Familia Church Has Been Under Construction for 136 Years. That's a Lot of Unpaid Permit Fees". Time. 19 October 2018.

- "Sagrada Familia gets building permit after 137 years". CNN.com. 9 June 2019.

Further reading

- Zerbst, Rainer (1988). Antoni Gaudi – A Life Devoted to Architecture. Trans. from German by Doris Jones and Jeremy Gaines. Hamburg, Germany: Taschen. ISBN 3-8228-0074-0.

- Nonell, Juan Bassegoda (2004). Antonio Gaudi: Master Architect. New York: Abbeville Press. ISBN 0-7892-0220-4.

- Hernandez SJ, Jean-Paul (2007). Pardes (ed.). Antoni Gaudi: La Parola nella pietra. I simboli e lo spirito della Sagrada Familia. Bologna, Italy. p. 114. ISBN 978-88-89241-31-8.

- Crippa, Maria Antonietta (2003). Peter Gossel (ed.). Antoni Gaudi, 1852–1926: From Nature to Architecture. Trans. Jeremy Carden. Hamburg, Germany: Taschen. ISBN 3-8228-2518-2.

- Schneider, Rolf (2004). Manfred Leier (ed.). 100 most beautiful cathedrals of the world: A journey through five continents. Trans. from German by Susan Ghyearuni and Rae Walter. Edison, New Jersey: Chartwell Books. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-7858-1888-5.

- Borja de Riquer i Permanye (2001). Modernisme i Modernistes. Barcelona: Gaudi, Lunwerg. ISBN 84-7782-776-1.

- Barral i Altet, Javier (2001). L'isard, Barcelona (ed.). Art de Catalunya. Arquitectura religiosa moderna i contemporània. ISBN 84-89931-14-3.

- Bassegoda i Nonell, Joan (1989). Ausa, Sabadell (ed.). El gran Gaudí. ISBN 84-86329-44-2.

- Bassegoda i Nonell, Joan (2002). Gaudí o espacio, luz y equilibrio. Madrid: Criterio Libros. ISBN 84-95437-10-4.

- Bergós i Massó, Joan (1999). Ed. Lunwerg, Barcelona (ed.). Gaudí, l'home i l'obra. ISBN 84-7782-617-X.

- Bonet i Armengol, Jordi (2001). Ed. Pòrtic, Barcelona (ed.). L'últim Gaudí. ISBN 84-7306-727-4.

- Crippa, Maria Antonietta (2007). Taschen, Köln (ed.). Gaudí. ISBN 978-3-8228-2519-8.

- Flores, Carlos (2002). Ed. Empúries, Barcelona (ed.). Les lliçons de Gaudí. ISBN 84-7596-949-6.

- Fontbona, Francesc; Miralles, Francesc (1985). Ed. 62, Barcelona (ed.). Història de l'Art Català. Del modernisme al noucentisme (1888–1917). ISBN 84-297-2282-3.

- Giralt-Miracle, Daniel (2002). Lunwerg (ed.). Gaudí, la busqueda de la forma. ISBN 84-7782-724-9.

- Gómez Gimeno, María José (2006). Mundo Flip Ediciones (ed.). La Sagrada Familia. ISBN 84-933983-4-9.

- Lacuesta, Raquele (2006). Diputació de Barcelona, Barcelona (ed.). Modernisme a l'entorn de Barcelona. ISBN 84-9803-158-3.

- Navascués Palácio, Pedro (2000). Espasa Calpe, Madrid (ed.). Summa Artis. Arquitectura española (1808–1914). ISBN 84-239-5477-3.

- Permanyer, Lluis (1993). Ed. Polígrafa, Barcelona (ed.). Barcelona modernista. ISBN 84-343-0723-5.

- Puig i Boada, Isidre (1986). Ed. Nou Art Thor, Barcelona (ed.). El temple de la Sagrada Família. ISBN 84-7327-135-1.

- Tarragona, Josep Maria (1999). Ed. Proa, Barcelona (ed.). Gaudí, biografia de l'artista. ISBN 84-8256-726-8.

- Van Zandt, Eleyearr (1997). Asppan (ed.). La vida y obras de Gaudí. ISBN 0-7525-1106-8.

- Zerbst, Rainer (1989). Taschen (ed.). Gaudí. ISBN 3-8228-0216-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sagrada Família. |

.jpg)