Olympic flame

The Olympic flame is a symbol used in the Olympic movement. It is also a symbol of continuity between ancient and modern games.[1] Several months before the Olympic Games, the Olympic flame is lit at Olympia, Greece. This ceremony starts the Olympic torch relay, which formally ends with the lighting of the Olympic cauldron during the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games. The flame then continues to burn in the cauldron for the duration of the Games, until it is extinguished during the Olympic closing ceremony.

Origins

Olympic flame

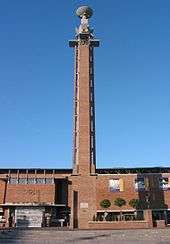

The Olympic flame as a symbol of the modern Olympic movement was introduced by architect Jan Wils who designed the stadium for the 1928 Summer Olympics in Amsterdam.

The idea for the Olympic flame was derived from ancient Greece, where a sacred fire was kept burning throughout the celebration of the ancient Olympics on the altar of the sanctuary of Hestia.[2][3] In Ancient Greek mythology, fire had divine connotations — it was thought to have been stolen from the gods by Prometheus. Sacred fires were present at many ancient Greek sanctuaries, including those at Olympia. Every four years, when Zeus was honoured at the Olympic Games, additional fires were lit at his temple and that of his wife, Hera. The modern Olympic flame is ignited at the site where the temple of Hera used to stand.

When the tradition of an Olympic fire was reintroduced during the 1928 Summer Olympics, an employee of the Electric Utility of Amsterdam lit the first modern Olympic flame in the Marathon Tower of the Olympic Stadium in Amsterdam.[4] The Olympic flame has been part of the Summer Olympics ever since. The Olympic flame was first introduced to the Winter Olympics at the 1936 Winter Olympics in Garmisch-Partenkirchen.

Olympic torch relay

By contrast to the Olympic flame, the Olympic torch relay, which transports the flame from Olympia, Greece to the various designated sites of the Games, had no ancient precedent and was introduced by Carl Diem at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin[5] which were organized by the Nazis under the guidance of Joseph Goebbels.

At the first Olympic torch relay, the flame was transported from Olympia to Berlin over 3,187 kilometres by 3,331 runners in twelve days and eleven nights. There were minor protests in Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia on the way, which were suppressed by the local security forces. Leni Riefenstahl later staged the torch relay for the 1938 film Olympia.[6]

Main ceremonies

Olympic flame lighting

The Olympic fire is ignited several months before the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games at the site of the ancient Olympics in Olympia, Greece.

Eleven women, representing the Vestal Virgins,[notes 1] perform a celebration at the Temple of Hera in which the first torch of the Olympic Torch Relay is kindled by the light of the Sun, its rays concentrated by a parabolic mirror.

At the beginning of the ceremony, the Olympic anthem was sung first followed by the national anthem of the country hosting the Olympics and the national anthem of Greece along with the hoisting of the flags.

Olympic torch relay

.jpg)

After the ceremony at Olympia, the Olympic flame first travels around Greece, and is then transferred during a ceremony in the Panathenaic Stadium in Athens from the prior Olympic city to the current year's host city.[7][8]

The Olympic torch relay in the host country ends with the lighting of the Olympic cauldron during the opening ceremony in the central host stadium of the Games. The final carrier is often kept unannounced until the last moment. Over the years, it has become a tradition to let a famous athlete of the host nation, former athletes or athletes with significant achievements and milestones be the last runner in the Olympic torch relay.

Notable torch relays

The Olympic torch travels routes that symbolise human achievement. Although most of the time the torch with the Olympic flame is still carried by runners, it has been transported in many different ways. The fire travelled by boat in 1948 and 2012 to cross the English Channel and was carried by rowers in Canberra as well as by dragon boat in Hong Kong in 2008.[9] It was first transported by airplane in 1952, when the fire travelled to Helsinki. In 1956, all carriers in the torch relay to Stockholm, where the equestrian events were held instead of in Melbourne, travelled on horseback.

Remarkable means of transportation were used in 1976, when the flame was transformed to a radio signal and transmitted from Europe to the New World: Heat sensors in Athens detected the flame, the signal was sent to Ottawa via satellite where it was received and used to trigger a laser beam to re-light the flame.[10][11] The torch, but not the flame, was taken into space by astronauts in 1996, 2000 and 2013.[12] Other unique means of transportation include a Native American canoe, a camel, and Concorde.[13] The torch has been carried across water; the 1968 Grenoble Winter Games was carried across the port of Marseilles by a diver holding it aloft above the water.[14] In 2000, an underwater flare was used by a diver across the Great Barrier Reef en route to the Sydney Games.[15] In 2012 it was carried by boat across Bristol harbour in the UK and on the front of a London Underground train to Wimbledon.

In 2004, the first global torch relay was undertaken, a journey that lasted 78 days. The Olympic flame covered a distance of more than 78,000 km in the hands of some 11,300 torchbearers, travelling to Africa and South America for the first time, visiting all previous Olympic cities and finally returning to Athens for the 2004 Summer Olympics. The 2008 Summer Olympics torch relay spanned all six inhabited continents before proceeding through China, but was met with protests in London, Paris, and San Francisco. As a result, in 2009, the International Olympic Committee announced that future torch relays could be held only within the country hosting the Olympics after the initial Greek leg. Although this rule took effect with the 2014 Winter Olympics, the organizers of the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver and the 2012 Summer Olympics in London chose to hold their torch relays only in their respective hosting countries of Canada and the United Kingdom[16] (except for brief stops in the United States and Ireland, respectively). The London 2012 torch travelled 8,000 miles across the UK. The Rio 2016 torch travelled 12,000 miles across Brazil.

Protests against relays

There have been protests against Olympic torch relays since they were first introduced. In 1936, there were minor protests against the torch relay to Nazi Germany in Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia, which were suppressed by the local security forces.

In the 1956 Melbourne Games in Australia, local veterinary student Barry Larkin protested against the relay when he tricked onlookers by carrying a fake flame, consisting of a pair of underpants set on fire in a plum pudding can, attached to a chair leg. He successfully managed to hand over the fake flame to the Mayor of Sydney, Pat Hills and escape without being noticed.[17][18][19]

In 2008 there were various attempts to stop the Olympic flame as a protest against China's human rights record. In London, a "ring of steel" was formed around the flame to protect it, but one protester managed to grab hold of the torch while it was being held by television presenter Konnie Huq.[20]

In 2016, ten days before the beginning of the Rio Games in Brazil, citizens of Angra dos Reis, a city near Rio de Janeiro, managed to put out the Olympic flame when protesting against the city's spending money on hosting the games, despite the economic crisis that took hold of Brazil.[21]

Re-igniting the flame

It is not uncommon for the Olympic flame to be accidentally or deliberately extinguished during the course of the torch relay (and on at least one occasion the cauldron itself has gone out during the Games). To guard against this eventuality, multiple copies of the flame are transported with the relay or maintained in backup locations. When a torch goes out, it is re-lit (or another torch is lit) from one of the backup sources. Thus, the fires contained in the torches and Olympic cauldrons all trace a common lineage back to the same Olympia lighting ceremony.

- One of the more memorable extinguishings occurred at the 1976 Summer Olympics held in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. After a rainstorm doused the Olympic flame a few days after the games had opened, an official re-lit the flame using a cigarette lighter. Organizers quickly doused it again and re-lit it using a backup of the original flame.[11]

- At the 2004 Summer Olympics, when the Olympic flame came to the Panathinaiko Stadium to start the global torch relay, the night was very windy and the torch, lit by Gianna Angelopoulos-Daskalaki of the Athens 2004 Organizing Committee, blew out due to the wind, but was re-lit from the backup flame taken from the original flame lit at Olympia.

- In 2008 the Olympic torch was extinguished at least twice by Chinese officials (five times according to French police[22]) so that it could be transported in a bus amid protests while it was being paraded through Paris.[23][24] This eventually led to the cancellation of the relay's last leg in the city.[25] The fire itself, however, remained preserved in the backup lantern used to keep it overnight and on airplanes, and the torch was re-lit using this flame.

- In October 2013 in Russia, the Olympic flame was blown out at the Kremlin and was reignited from a security officer's lighter instead of the back up flame.[26]

The current design of the torch has a safeguard built into it: There are two flames inside the torch. There is a highly visible (yellow flame) portion which burns cooler and is more prone to extinguish in wind and rain, but there is also a smaller hotter (blue in the candle's wick) flame akin to a pilot light hidden inside the torch which is protected from wind and rain and is capable of relighting the cooler more visible portion if it is extinguished. The fuel inside the torch lasts for approximately 15 minutes before the flame is exhausted.[27]

Selected relays in detail

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Olympic torches and torch relays. |

.jpg)

- 1936 Summer Olympics torch relay

- Cancelled 1940 Summer Olympics torch relay

- 1948 Summer Olympics torch relay

- 1952 Winter Olympics torch relay

- 1968 Summer Olympics torch relay

- 1976 Summer Olympics torch relay

- 1980 Summer Olympics torch relay

- 1984 Winter Olympics torch relay

- 1984 Summer Olympics torch relay

- 1988 Winter Olympics torch relay

- 1988 Summer Olympics torch relay

- 1992 Winter Olympics torch relay

- 1992 Summer Olympics torch relay

- 1994 Winter Olympics torch relay

- 1996 Summer Olympics torch relay

- 1998 Winter Olympics torch relay

- 2000 Summer Olympics torch relay

- 2002 Winter Olympics torch relay

- 2004 Summer Olympics torch relay

- 2006 Winter Olympics torch relay

- 2008 Summer Olympics torch relay

- 2008 Summer Paralympics torch relay

- 2010 Winter Olympics torch relay

- 2010 Winter Paralympics torch relay

- 2010 Summer Youth Olympics torch relay

- 2012 Summer Olympics torch relay

- 2012 Summer Paralympics torch relay

- 2014 Winter Olympics torch relay

- 2014 Winter Paralympics torch relay

- 2016 Summer Olympics torch relay

- 2016 Summer Paralympics torch relay

- 2018 Winter Olympics torch relay

- 2018 Winter Paralympics torch relay

- 2020 Summer Olympics torch relay

- 2020 Summer Paralympics torch relay

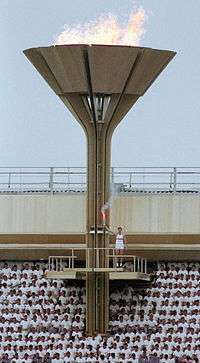

Olympic cauldron lighting

During the opening ceremony, the final bearer of the torch runs towards the cauldron, often placed at the top of a grand staircase, and then uses the torch to start the flame in the stadium. The climactic transfer of the Olympic flame from the final torch to the cauldron at the central host stadium marks the symbolic commencement of the Games.

As with being the final runner of the Olympic torch relay, it is considered to be a great honor to light the Olympic cauldron, and similarly it has become a tradition to select notable athletes to conduct this part of the ceremony.

After being lit, the flame in the Olympic cauldron continues to burn throughout the Games, until the closing ceremony, when it is finally put out, symbolizing the official end of the Games.

Notable cauldron ceremonies

The first well-known athlete to light the cauldron in the stadium was ninefold Olympic Champion Paavo Nurmi, who excited the home crowd in Helsinki in 1952. In 1968, Enriqueta Basilio became the first woman to light the Olympic Cauldron at the Olympic Games in Mexico City.

Perhaps one of the most spectacular of Olympic cauldron lighting ceremonies took place at the 1992 Summer Olympics, when Paralympic archer Antonio Rebollo lit the cauldron by shooting a burning arrow over it, which ignited gas rising from the cauldron.[28][28][29] Unofficial videos seem to indicate that the flame was lit from below.[30][31] Twenty years after the Barcelona Games one of those involved said that the flame was "switched on" ("Se encendió con un botón", in Spanish).[32] Two years later, the Olympic fire was brought into the stadium of Lillehammer by a ski jumper. In Beijing 2008, Li Ning "ran" on air around the Bird's Nest and lit the flame.

In Vancouver 2010, four athletes—Catriona Le May Doan, Wayne Gretzky, Steve Nash and Nancy Greene—were given the honour of lighting the flame simultaneously indoors before Wayne Gretzky transferred the flame to an outdoor cauldron at Vancouver's waterfront. Other famous last bearers of the torch include heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali (1996), Australian aboriginal runner Cathy Freeman (2000) and the and more recently Brazilian marathon runner Vanderlei Cordeiro de Lima (2016), and South Korean figure skater Yuna Kim (2018).

On other occasions, the people who lit the cauldron in the stadium are not famous, but nevertheless symbolize Olympic ideals. Japanese runner Yoshinori Sakai was born in Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, the day the United States destroyed that city with the nuclear weapon Little Boy. He symbolized the rebirth of Japan after the Second World War when he opened the 1964 Tokyo Games. At the 1976 Games in Montreal, two teenagers — one from the French-speaking part of the country, one from the English-speaking part — symbolized the unity of Canada.

At the 2012 Games in London, the torch was carried by Sir Steve Redgrave to a group of seven young British athletes (Callum Airlie, Jordan Duckitt, Desiree Henry, Katie Kirk, Cameron MacRitchie, Aidan Reynolds and Adelle Tracey) — each nominated by a British Olympic champion — who then each lit a single tiny flame on the ground, igniting 204 copper petals before they converged to form the cauldron for the Games.

Design of equipment used

Olympic torch designs

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Olympic torches. |

The design of the torch used in the relay to the Games changes for each Games. They may be designed to represent a classical ideal, or to represent some local aspect of those particular Games.[14][33][34]

The first Olympic torches in 1936 were produced by the Krupp armaments company in wood and metal, inspired by an olive leaf. The distinctive 1976 torch was manufactured by John L. Saksun's The Queensway Machine Products Ltd. Some (such as Albertville in 1992 and Turin in 2006) have been designed by famous industrial designers. These design-led torches have been less popular than the more classical designs, the Turin torch in particular was criticised for being simply too heavy for the runners.

The torch for the 1948 London Olympics was designed by architect Ralph Lavers.[35] They were cast in Hiduminium aluminium alloy[36] with a length of 47 cm and a weight of 960 g. This classical design of a long handle capped by a cylindrical bowl re-appeared in many later torch designs. The torch used for the final entry to the stadium and the lighting of the cauldron was of a different design, also a feature that would re-appear in later years. This torch did not require the long distance duration or weather resistance of the other torches, but did need a spectacular flame for the opening ceremony.

At the Melbourne Olympics of 1956, the magnesium/aluminium fuel used for the final torch was certainly spectacular, but also injured its holder.[15] Runners were also burned by the solid-fueled torch for the 1968 Mexico Games. The fuel used for the torch has varied. Early torches used solid or liquid fuels, including olive oil.[37]

For a particularly bright display, pyrotechnic compounds and even burning metals have been used. Since the Munich Games of 1972, most torches have instead used a liquefied gas such as propylene or a propane/butane mixture. These are easily stored, easily controlled and give a brightly luminous flame.

The number of torches made has varied from, for example, 22 for Helsinki in 1952, 6,200 for the 1980 Moscow Games[14] and 8,000 for the London 2012 Games. In transit, the flame sometimes travels by air. A version of the miner's safety lamp is used, kept alight in the air. These lamps are also used during the relay, as a back-up in case the primary torch goes out. This has happened before several Games, but the torch is simply re-lit and carries on.

Berlin 1936 torch

Berlin 1936 torch- 1948 London torch

Cortina 1956 torch

Cortina 1956 torch- Melbourne 1956 torch

Rome 1960 Torch

Rome 1960 Torch- Tokyo 1964 torch

Grenoble 1968 torch

Grenoble 1968 torch Mexico 1968 torch

Mexico 1968 torch Innsbruck 1976 torch

Innsbruck 1976 torch Montreal 1976 torch

Montreal 1976 torch- Sydney 2000 torch

- Athens 2004 torch

Turin 2006 torch

Turin 2006 torch Beijing 2008 torch

Beijing 2008 torch Vancouver 2010 torch

Vancouver 2010 torch London 2012 torch

London 2012 torch.png) Sochi 2014 torch

Sochi 2014 torch Rio 2016 torch

Rio 2016 torch PyeongChang 2018 torch

PyeongChang 2018 torch

Olympic cauldron designs

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Olympic cauldrons. |

The cauldron and the pedestal are always the subject of unique and often dramatic design. These also tie in with how the cauldron is lit during the Opening Ceremony.

- In Los Angeles in 1984, Rafer Johnson lit a wick of sorts at the top of the archway after having climbed a big flight of steps. The flame flared up a pipe, through the Olympic Rings and on up the side of the tower to ignite the cauldron.

- In Atlanta in 1996, the cauldron was an artistic scroll decorated in red and gold. It was lit by Muhammad Ali, using a mechanical, self-propelling fuse ball that transported the flame up a wire from the stadium to its cauldron.[38] At the 1996 Summer Paralympics, the scroll was lit by paraplegic climber Mark Wellman, hoisting himself up a rope to the cauldron.

- For the 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney, Cathy Freeman walked across a circular pool of water and ignited the cauldron through the water, surrounding herself within a ring of fire. The planned spectacular climax to the ceremony was delayed by the technical glitch of a computer switch which malfunctioned, causing the sequence to shut down by giving a false reading. This meant that the Olympic flame was suspended in mid-air for about four minutes, rather than immediately rising up a water-covered ramp to the top of the stadium. When it was discovered what the problem was, the program was overridden and the cauldron continued up the ramp, where it finally rested on a tall silver pedestal.

- For the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City, Utah, United States, the cauldron was lit by the members of the winning 1980 US hockey team. After being skated around the centre ice rink there in the stadium, the flame was carried up a staircase to the team members, who then lit a wick of sorts at the bottom of the cauldron tower which set off a line of flames that travelled up inside the tower until it reached the cauldron at the top which ignited. This cauldron was the first to use glass and incorporated running water to prevent the glass from heating and to keep it clean.

- For the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens, the cauldron was in the shape of a giant olive leaf which bowed down to accept the flame from windsurfer Nikolaos Kaklamanakis.[39]

- In the 2006 Winter Olympics in Turin, Stefania Belmondo placed the flame on an arched lighting apparatus, which initiated a series of fireworks before lighting the top of the 57-metre-high (187 ft) Olympic cauldron, the highest in the history of the Winter Olympic Games.[40]

- In the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, the cauldron resembled the end of a scroll that lifted out from the stadium rim and spiralled upwards. It was lit by Li Ning, who was raised to the rim of the stadium by wires. He ran around the rim of the stadium while suspended and as he ran, an unrolling scroll was projected showing film clips of the flame's journey around the world from Greece to Beijing. As he approached the cauldron, he lit an enormous wick, which then transferred the flame to the cauldron. The flame then spiralled up the structure of the cauldron before lighting it at the top.[41]

- In the 2010 Winter Olympics at Vancouver, a team of athletes (Catriona Le May Doan, Steve Nash, Nancy Greene and Wayne Gretzky) were to simultaneously light the base of poles, which would then carry the flames upwards to the cauldron. However, only three out of four poles came out of the ground due to mechanical problems, resulting in inadvertently excluding Le May Doan from lighting it with the other three athletes. Because the site of the ceremonies - BC Place - was a domed stadium, Gretzky was sent via the back of a pick-up truck to a secondary site — the Vancouver Convention Centre which served as the International Broadcast Centre for these Olympics — to light a larger cauldron of a similar design located outdoors, as Olympic rules state that the flame must be in public view for the entirety of the Olympics. In the closing ceremonies, Le May Doan took part in a joke about the mechanical glitch, and she was able to light the fully raised fourth pole and have the indoor cauldron relit.

- At the 2012 Summer Olympics in London, the flame was passed to a group of seven young British athletes (Callum Airlie, Jordan Duckitt, Desiree Henry, Katie Kirk, Cameron MacRitchie, Aidan Reynolds, and Adelle Tracey) who then each lit a single tiny flame on the ground, igniting 204 petals. The cauldron that traditionally flames continuously from the opening until the closing ceremony was temporarily extinguished (the flame itself was transferred to a lantern) prior to the athletics events while the cauldron was moved to the southern side of the stadium. It was relit by Austin Playfoot, a torchbearer from the 1948 Olympics.[42] In contrast to the cauldrons in Vancouver, the cauldron was not visible to the public outside the stadium. Instead, monitors had been placed throughout the Olympic Park showing the public live footage of the flame.

- For the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia, the cauldron was situated directly outside Fisht Olympic Stadium, the ceremonial venue for the Games. After the torch's lap around the stadium, Irina Rodnina and Vladislav Tretiak carried the torch outside the stadium to light a larger version of the "celebration cauldron" used in the main torch relay at the center of the Olympic Park. A line of gas jets carried the flame from the celebration cauldron up the main cauldron tower, eventually lighting it at the top.

- For the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the cauldron was lit inside the Maracanã Stadium, the ceremonial venue for the Games, by Vanderlei de Lima. As part of these Games' appeal towards environmental protection, organizers deliberately chose to use a basic design with a smaller flame than past cauldrons. To compensate for the smaller cauldron, it is accompanied by a larger kinetic sculpture designed by Anthony Howe. A very similar public cauldron was lit in a plaza outside the Candelária Church following the opening ceremony.[43][44][45]

- For the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, South Korea, the flame was eventually handed to Yuna Kim, who was at the top of a set of steps. She then lit a wick of sorts, which lit a large metal flaming pillar. The pillar rose to the top of the cauldron, lighting it. The cauldron was a large white sculpture with a large sphere on the top, acting for the cauldron. The cauldron's design was inspired by Joseon white porcelain.

Traditional Olympic cauldrons often employ a simple bowl-on-pedestal design, such as the cauldron used for the 1936 Summer Olympics

Traditional Olympic cauldrons often employ a simple bowl-on-pedestal design, such as the cauldron used for the 1936 Summer Olympics Olympic cauldron at Moscow 1980

Olympic cauldron at Moscow 1980 Olympic cauldron at Seoul 1988, during the opening ceremony

Olympic cauldron at Seoul 1988, during the opening ceremony_-_panoramio.jpg) Olympic cauldron at Barcelona 1992

Olympic cauldron at Barcelona 1992 Olympic cauldron at Atlanta 1996

Olympic cauldron at Atlanta 1996 Olympic cauldron at Athens 2004 during the opening ceremony

Olympic cauldron at Athens 2004 during the opening ceremony Olympic cauldron at Turin 2006

Olympic cauldron at Turin 2006- Olympic cauldron at Beijing 2008 during the opening ceremony

Olympic cauldron during the Vancouver 2010 Olympic Winter Games

Olympic cauldron during the Vancouver 2010 Olympic Winter Games.jpg) More artistic and abstract designs for cauldrons, including the 2012 Summer Olympics cauldron, have also been used.

More artistic and abstract designs for cauldrons, including the 2012 Summer Olympics cauldron, have also been used..jpg) Cauldrons can also take on monolithic forms, an example of which being the "cauldron tower" used for the 2014 Winter Olympics

Cauldrons can also take on monolithic forms, an example of which being the "cauldron tower" used for the 2014 Winter Olympics The 2016 cauldron features a kinetic sculpture with a small flame.

The 2016 cauldron features a kinetic sculpture with a small flame. The 2016 Olympics public cauldron, in a plaza at downtown Rio de Janeiro

The 2016 Olympics public cauldron, in a plaza at downtown Rio de Janeiro Olympic Cauldron at PyeongChang 2018

Olympic Cauldron at PyeongChang 2018

Coinage

The Olympic flame has been used as a symbol and main motif numerous times in different commemorative coins. A recent sample was the 50th anniversary of the Helsinki Olympic Games commemorative coin, minted in 2002. In the obverse, the Olympic flame above the Earth can be seen. Note that Finland is the only country highlighted, as the host of the 1952 games.

See also

- Flame of Hope (Special Olympics)

- Queen's Baton Relay, an analogous relay associated with the Commonwealth Games

- Pan American Torch, a torch relay associated with the Pan American Games

- Asian Games Torch, a torch relay associated with the Asian Games

- Universiade Torch, a torch relay associated with the Universiade

- Eternal flame

Notes

- "Beijing 2008 Olympic Games - History of the Olympic Games". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- "Report" (PDF). Official website of the Olympic Movement. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- (secondary)Jean-Pierre Vernant - Hestia - Hermes : The religious expression of space and movement among the Greeks Archived 14 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 19 May 2012

- "Amsterdam 1928". Olympic.org. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- "Hitler's Berlin Games Helped Make Some Emblems Popular". Sports > Olympics. The New York Times. 14 August 2004. Archived from the original on 24 April 2009. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- Adolf Hitler saw the link with the ancient Games as the perfect way to illustrate his belief that classical Greece was an Aryan forerunner of the modern German Reich. (See Hines, Nico (7 April 2008). "Who put the Olympic flame out?". timesonline.co.uk. London. Retrieved 7 April 2008.)

- "Olympic Torch Relay history". London 2012 Olympic Games. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- Ranger, A. "The Panathenaic". http://www.panathenaicstadium.gr/thepanathenaicstadium/history/tabid/96/language/en-us/default.aspx. Panathenaic Stadium 2011. Retrieved 14 July 2016. External link in

|website=(help) - 施幸余乘龍舟傳送火炬 (in Chinese). Singtao. 2 May 2008. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- Winn, L.: Olympic Design: Torches & Cauldrons. Sports Illustrated, 17 Feb 2010.

- "Montréal". The Olympic Museum Lausanne. International Olympic Committee. Archived from the original on 8 February 2002.

- The Olympic Torch Relay: Olympic Torch Relay Highlights

- "Report" (PDF). 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2006.

- "Torch Timeline". BBC News online. 18 May 2011.

- "Olympic torch technology". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2000.

Australian runner, Ron Clarke carried a spectacular, fizzling flame into the Melbourne Olympic Stadium in 1956 only to miss out on the ceremony having his magnesium burns dressed.

- Zinser, Lynn (27 March 2009). "I.O.C. Bars International Torch Relays". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- "Olympic Underwear Relay". The Birdman. Archived from the original on 13 April 2008. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- Stephen Fry (2007). QI Presents: Strictly Come Duncing (DVD). Warner Music Entertainment.

- Turpin, Adrian (8 August 2004). "Olympics Special: The Lost Olympians (Page 1)". Find Articles, originally The Independent on Sunday. Archived from the original on 13 April 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2008.

- Lews, Paul; Kelso, Paul (7 April 2008). "Thousands protest as Olympic flame carried through London". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- "PROTESTERS PUT OUT THE OLYMPIC TORCH IN RIO". Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- (in French) "Flamme olympique: ce qui s'est vraiment passé à Paris" Archived 12 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine, L'Express, 8 April 2008

- "Paris protests force Olympic flame to be extinguished". This is London. 4 April 2008. Archived from the original on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 19 April 2008. External link in

|publisher=(help) - "China condemns Olympic torch disruptions" Archived 23 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine, France 24, 8 April 2008

- "Paris protests force cancellation of torch relay". msnbc.com. 7 April 2008. Archived from the original on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2008.

- Withnall, Adam (7 October 2013). "Got a light? Olympic flame goes out in 'wind tunnel' at Kremlin - and is reborn on the sly via a security officer's cigarette lighter". The Independent. London.

- "The Olympic torch". Entertainment. How Stuff Works.

- Official Report of the 1992 Summer Olympics, Vol. 4, p. 70 (confirming arrow lit the gas above the cauldron) and p. 69 (time-lapse photo of lighting; the arrow passed through the upper reaches of the flame).

- Mathews, John (15 September 2000). "Ceremonial hall of shame". BBC Sport.

- La flecha olimpica no entró!, retrieved 21 September 2019

- Lighting of the cauldron, another unofficial recording on YouTube.

- "ETA puso una bomba en el Palau Sant Jordi en los Juegos de 1992". La Vanguardia. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- Byron, Lee; Desantis, Alicia (9 February 2010). "Passing the Torch: An Evolution of Form". New York Times.

- "Pictures of all Olympic Summergames Torches". olympic-museum.de.

- "Olympic Torch, London 1948". Metalwork. Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 6 January 2008. Retrieved 19 November 2007.

- "1948 Olympics" (PDF). Flight (Here and There ed.): 90. 22 July 1948.

- "How Olympic Torches Work". HowStuffWorks. 7 August 2004. Archived from the original on 21 September 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- 1996 Atlanta Opening Ceremonies — Lighting of the Cauldron on YouTube

- 2004 picture, BBC News

- Olympic Opening Ceremony Torino 2006 - Light of Passion on YouTube

- Olympic (8 August 2019). "Full Opening Ceremony from Beijing 2008 - Throwback Thursday" – via YouTube.

- Taylor, Matthew (30 July 2012). "Olympic cauldron relit after move to southern end of stadium". The Guardian. London.

- "Diminutive Rio 2016 cauldron complemented by massive kinetic sculpture". Dezeen. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- "Sun sculpture and cauldron light up Olympic ceremony..." The Telegraph. 6 August 2016.

- "Formerly homeless boy who lit Olympic cauldron now has 'beautiful life'". CBC News. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

References

- Volker Kluge. 1997-2004. Olympische Sommerspiele – Die Chronik. Five volumes. Sportverlag except Vol. 5 (Südwest-Verlag). ISBN 3-328-00715-6; ISBN 3-328-00740-7; ISBN 3-328-00741-5; ISBN 3-328-00830-6; ISBN 3-517-06732-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Olympic Flame. |

- Olympic Flame Lighting Ceremony for PyeongChang 2018 on YouTube

- Olympic Flame Lighting Ceremony for Rio 2016 on YouTube

- Official site of the Olympic Movement - Images and information on every game since 1896

- IOC brochure on the history of Olympic flame (1 MB PDF)

- TorchRelay.net - Torch Relay coverage. Includes torchbearer profiles, photos, videos, and more.

- Athens Info Guide - A list of past torches

- Sondre Norheim - on the three occasions when the Olympic flame was lit in Morgedal

- BBC article on the history of the torch

- The Nazi Olympics: Berlin 1936 - online exhibition