Austrian People's Party

The Austrian People's Party (German: Österreichische Volkspartei, ÖVP) is a conservative[1][2] and Christian-democratic[3][4][5] political party in Austria.

Austrian People's Party Österreichische Volkspartei | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | ÖVP |

| Chairman | Sebastian Kurz |

| Secretary-General | Karl Nehammer |

| Parliamentary leader | August Wöginger |

| Managing director | Axel Melchior |

| Founded | 17 April 1945 |

| Headquarters | Lichtenfelsgasse 7 A-1010 Vienna, Austria |

| Youth wing | Young People's Party |

| Ideology | Conservatism[1][2] Christian democracy[3][4][5] Liberal conservatism[6] Factions Centrism[7] Economic liberalism[8] Right-wing populism[9] |

| Political position | Centre-right[10] to right-wing[11] |

| European affiliation | European People's Party |

| International affiliation | International Democrat Union |

| European Parliament group | European People's Party |

| Colours | Cyan (since 2017) Black (before 2017) |

| National Council | 71 / 183 |

| Federal Council | 22 / 61 |

| Governorships | 6 / 9 |

| State cabinets | 7 / 9 |

| State diets | 141 / 440 |

| European Parliament | 7 / 19 |

| Website | |

| dieneuevolkspartei | |

An unofficial successor to the Christian Social Party of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was founded immediately following the reestablishment of the Republic of Austria in 1945 and since then has been one of the two largest Austrian political parties with the Social Democratic Party of Austria (SPÖ). In federal governance, the ÖVP has spent most of the postwar era in a grand coalition with the SPÖ. However, the ÖVP won the 2017 Austrian legislative election, having the greatest number of seats and formed a coalition with the right-wing populist Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ). Its chairman Sebastian Kurz is the youngest Chancellor in Austrian history and currently the world's youngest leader.[12][13]

Until 2017, when the party's colour was changed to cyan, the ÖVP's party colour was black.

Platform

The ÖVP is conservative. For most of its existence, it has explicitly defined itself as Catholic and anti-socialist, with the ideals of subsidiarity as defined by the encyclical Quadragesimo anno and decentralisation.

For the first election after World War II, the ÖVP presented itself as the Austrian Party (German: die österreichische Partei), was anti-Marxist and regarded itself as the Party of the Center (German: Partei der Mitte). The ÖVP consistently held power—either alone or in so-called black–red coalition with the Social Democratic Party of Austria (SPÖ)—until 1970, when the SPÖ formed a minority government with the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ). The ÖVP's economic policies during the era generally upheld a social market economy.

The party's campaign for the 2017 Austrian legislative election under the young chairman Sebastian Kurz was dominated by a rightward shift in policy which included a promised crackdown on illegal immigration and a fight against political Islam,[14] making it more similar to the program of the FPÖ, the party that Kurz chose as his coalition partner after the ÖVP won the election.

History

The ÖVP is the successor of the Christian Social Party, a staunchly conservative movement founded in 1893 by Karl Lueger, mayor of Vienna and highly controversial right-wing populist. Most of the members of the party during its founding belonged to the former Fatherland Front, which was led by chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss, also a member of the Christian Social Party before the Anschluss. While still sometimes honored by ÖVP members for resisting Adolf Hitler, the regime built by Dollfuss was authoritarian in nature and has been dubbed as Austrofascism. In its present form, the ÖVP was established immediately after the restoration of Austria's independence in 1945 and it has been represented in both the Federal Assembly ever since. In terms of Federal Assembly seats, the ÖVP has consistently been the strongest or second-strongest party and as such it has led or at least been a partner in most Austria's federal cabinets.

In the 1945 Austrian legislative election, the ÖVP won a landslide victory in Austria's first postwar election, winning almost half the popular vote and an absolute majority in the legislature. However, memories of the hyper-partisanship that had plagued the First Republic prompted the ÖVP to maintain the grand coalition with the Communist Party of Austria (KPÖ) and the Social Democratic Party of Austria (SPÖ) that had governed the country since the restoration of independence in early 1945. The ÖVP remained the senior partner in a coalition with the SPÖ until 1966 and governed alone from 1966 to 1970. It reentered the government in 1986, but has never been completely out of power since the restoration of Austrian independence in 1945 due to a longstanding tradition that all major interest groups were to be consulted on policy.

After the 1999 Austrian legislative election, several months of negotiations ended in early 2000 when the ÖVP formed a coalition government with the right-wing populist Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) led by Jörg Haider. The FPÖ had won just a few hundred more votes than the ÖVP, but was considered far too controversial to lead a government. The ÖVP's Wolfgang Schüssel became Chancellor—the first ÖVP Chancellor of Austria since 1970. This caused widespread outrage in Europe and the European Union imposed informal diplomatic sanctions on Austria, the first time that it imposed sanctions on a member state. Bilateral relations were frozen (including contacts and meetings at an inter-governmental level) and Austrian candidates would not be supported for posts in European Union international offices.[15] Austria threatened to veto all applications by countries for European Union membership until the sanctions were lifted.[16] A few months later, these sanctions were dropped as a result of a fact-finding mission by three former European prime ministers, the so-called "three wise men". The 2002 legislative election resulted in a landslide victory (42.27% of the vote) for the ÖVP under Schüssel. Haider's FPÖ was reduced to 10.16% of the vote. At the state level, the ÖVP has long dominated the rural states of Lower Austria, Upper Austria, Salzburg, Styria, Tyrol and Vorarlberg. It is less popular in the city state of Vienna and in the rural, but less strongly Catholic states of Burgenland and Carinthia. In 2004, it lost its plurality in the State of Salzburg, where they kept its result in seats (14) in 2009. In 2005, it lost its plurality in Styria for the first time.

After the Alliance for the Future of Austria (BZÖ) split from the FPÖ in 2005, the BZÖ replaced the FPÖ in the government coalition which lasted until 2007. Austria for the first time had a government containing of a party that was founded during the parliamentary term. In the 2006 Austrian legislative election, the ÖVP were defeated and after much negotiations agreed to become junior partner in a grand coalition with the SPÖ, with new party chairman Wilhelm Molterer as Finance Minister and Vice-Chancellor under SPÖ leader Alfred Gusenbauer, who became Chancellor. The 2008 Austrian legislative election saw the ÖVP lose 15 seats, with a further 8.35% decrease in its share of the vote. However, the ÖVP won the largest share of the vote (30.0%) in the 2009 European Parliament election with 846,709, votes, although their number of seats remained the same.

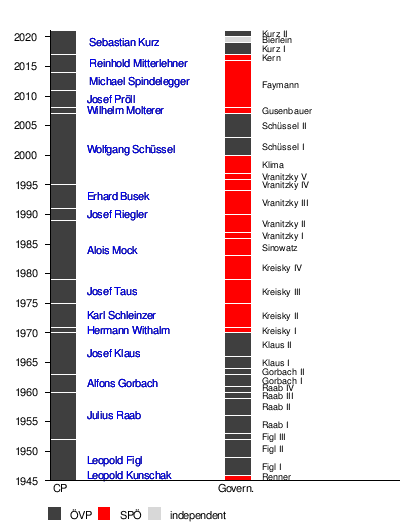

Chairpersons since 1945

The chart below shows a timeline of ÖVP chairpersons and the Chancellors of Austria. The left black bar shows all the chairpersons (Bundesparteiobleute, abbreviated as CP) of the ÖVP party and the right bar shows the corresponding make-up of the Austrian government at that time. The red (SPÖ) and black (ÖVP) colours correspond to which party led the federal government (Bundesregierung, abbreviated as Govern.). The last names of the respective Chancellors are shown, with the Roman numeral standing for the cabinets.

Election results

National Council

| National Council | ||||

| Election | Votes | % | Seats | Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1945 | 1,602,227 (1st) | 49.8% | 85 / 165 |

ÖVP–SPÖ–KPÖ majority |

| 1949 | 1,846,581 (1st) | 44.0% | 77 / 165 |

ÖVP–SPÖ majority |

| 1953 | 1,781,777 (2nd) | 41.3% | 74 / 165 |

SPÖ–ÖVP majority |

| 1956 | 1,999,986 (1st) | 46.0% | 82 / 165 |

ÖVP–SPÖ majority |

| 1959 | 1,928,043 (2nd) | 44.2% | 79 / 165 |

ÖVP–SPÖ majority |

| 1962 | 2,024,501 (1st) | 45.4% | 81 / 165 |

ÖVP–SPÖ majority |

| 1966 | 2,191,109 (1st) | 48.3% | 85 / 165 |

ÖVP majority |

| 1970 | 2,051,012 (2nd) | 44.7% | 78 / 165 |

In opposition |

| 1971 | 1,964,713 (2nd) | 43.1% | 80 / 183 |

In opposition |

| 1975 | 1,981,291 (2nd) | 42.9% | 80 / 183 |

In opposition |

| 1979 | 1,981,739 (2nd) | 41.9% | 77 / 183 |

In opposition |

| 1983 | 2,097,808 (2nd) | 43.2% | 81 / 183 |

In opposition |

| 1986 | 2,003,663 (2nd) | 41.3% | 77 / 183 |

SPÖ–ÖVP majority |

| 1990 | 1,508,600 (2nd) | 32.1% | 60 / 183 |

SPÖ–ÖVP majority |

| 1994 | 1,281,846 (2nd) | 27.7% | 52 / 183 |

SPÖ–ÖVP majority |

| 1995 | 1,370,510 (2nd) | 28.3% | 52 / 183 |

SPÖ–ÖVP majority |

| 1999 | 1,243,672 (3rd) | 26.9% | 52 / 183 |

ÖVP–FPÖ majority |

| 2002 | 2,076,833 (1st) | 42.3% | 79 / 183 |

ÖVP–FPÖ majority |

| 2006 | 1,616,493 (2nd) | 34.3% | 66 / 183 |

SPÖ–ÖVP majority |

| 2008 | 1,269,656 (2nd) | 26.0% | 51 / 183 |

SPÖ–ÖVP majority |

| 2013 | 1,125,876 (2nd) | 24.0% | 47 / 183 |

SPÖ–ÖVP majority |

| 2017 | 1,341,930 (1st) | 31.5% | 62 / 183 |

ÖVP–FPÖ majority |

| 2019 | 1,789,417 (1st) | 37.5% | 71 / 183 |

ÖVP–GRÜNE majority |

President

| Federal Presidency of the Republic of Austria | |||||||

| Election | Candidate | First round | Second round | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Result | Votes | % | Result | ||

| 1951 | Heinrich Gleißner | 1,725,451 | 40.1% | Runner-up | 2,006,322 | 47.9% | Lost |

| 1957 | Wolfgang Denk | 2,159,604 | 48.9% | Lost | |||

| 1963 | Julius Raab | 1,814,125 | 40.6% | Lost | |||

| 1965 | Alfons Gorbach | 2,324,436 | 49.3% | Lost | |||

| 1971 | Kurt Waldheim | 2,224,809 | 47.2% | Lost | |||

| 1974 | Alois Lugger | 2,238,470 | 48.3% | Lost | |||

| 1980 | Rudolf Kirchschläger | 3,538,748 | 79.9% | Won | |||

| 1986 | Kurt Waldheim | 2,343,463 | 49.6% | Runner-up | 2,464,787 | 53.9% | Won |

| 1992 | Thomas Klestil | 1,728,234 | 37.2% | Runner-up | 2,528,006 | 56.9% | Won |

| 1998 | Thomas Klestil | 2,644,034 | 63.4% | Won | |||

| 2004 | Benita Ferrero-Waldner | 1,969,326 | 47.6% | Lost | |||

| 2010 | No candidate | ||||||

| 2016 | Andreas Khol | 475,767 | 11.1% | 5th place | |||

European Parliament

| European Parliament | |||||

| Election | Votes | % | Seats | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 1,124,921 (1st) | 29.7% | 7 / 21 | ||

| 1999 | 859,175 (2nd) | 30.7% | 7 / 21 | ||

| 2004 | 817,716 (2nd) | 32.7% | 6 / 18 | ||

| 2009 | 858,921 (1st) | 30.0% | 6 / 17 | ||

| 2014 | 761,896 (1st) | 27.0% | 5 / 18 | ||

| 2019 | 1,305,954 (1st) | 34.6% | 7 / 18 | ||

State Parliaments

| State | Year | Votes | % | Seats | Government | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | +/- | Pos. | |||||

| Burgenland | 2020 | 56,728 | 30.6 (2nd) |

11 / 36 |

Opposition | ||

| Carinthia | 2018 | 45,438 | 15.4 (3rd) |

6 / 36 |

SPÖ–ÖVP | ||

| Lower Austria | 2018 | 450,812 | 49.6 (1st) |

29 / 56 |

ÖVP–SPÖ–FPÖ | ||

| Salzburg | 2018 | 94,642 | 37.8 (1st) |

15 / 36 |

ÖVP–Grüne–NEOS | ||

| Styria | 2019 | 217,036 | 36.0 (1st) |

18 / 48 |

ÖVP–SPÖ | ||

| Tyrol | 2018 | 141,691 | 44.3 (1st) |

17 / 36 |

ÖVP–Grüne | ||

| Upper Austria | 2015 | 316,290 | 36.4 (1st) |

21 / 56 |

ÖVP–FPÖ–SPÖ–Grüne | ||

| Vienna | 2015 | 76,958 | 9.2 (4th) |

7 / 100 |

Opposition | ||

| Vorarlberg | 2019 | 71,911 | 43.5 (1st) |

17 / 36 |

ÖVP–Grüne | ||

Symbols

.svg.png) Logo used in the 1980s

Logo used in the 1980s Logo before 2017

Logo before 2017 Logo with flag before 2017

Logo with flag before 2017 Turquoise variant of the text-logo since 2017

Turquoise variant of the text-logo since 2017

References

- Edgar Grande; Martin Dolezal; Marc Helbling; Dominic Höglinger (2012). Political Conflict in Western Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-107-02438-0. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- Terri E. Givens (2005). Voting Radical Right in Western Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-139-44670-9. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- Gary Marks; Carole Wilson (1999). "National Parties and the Contestation of Europe". In T. Banchoff; Mitchell P. Smith (eds.). Legitimacy and the European Union. Taylor & Francis. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-415-18188-4. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- André Krouwel (2012). Party Transformations in European Democracies. SUNY Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-1-4384-4483-3. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- Ari-Veikko Anttiroiko; Matti Mälkiä, eds. (2007). Encyclopedia of Digital Government. Idea Group Inc (IGI). p. 390. ISBN 978-1-59140-790-4. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- Ralph P Güntzel (2010). Understanding "Old Europe": An Introduction to the Culture, Politics, and History of France, Germany, and Austria. Tectum Wissenschaftsverlag. p. 162. ISBN 978-3-8288-5300-3.

- Derbyshire, J. Denis (2016). Encyclopedia of World Political Systems. Taylor & Francis. p. 114.

- Country Profile: Austria. The Unit. 2001. p. 9.

- Barbara Tóth (7 January 2020). "Austria's political experiment". International Politics and Society.

-

- Connolly, Kate; Oltermann, Philip; Henley, Jon (23 May 2016). "Austria elects Green candidate as president in narrow defeat for far right". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- Clarke, Hilary; Halasz, Stephanie; Vonberg, Judith. "Coalition government with far-right party takes power in Austria". CNN. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- "The Latest: Election tally shows Austria turning right". The Washington Times. Associated Press. 15 October 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- Oliphant, Roland; Csekö, Balazs (5 December 2016). "Austrian far-right defiant as Freedom Party claims 'pole position' for general election: 'Our time comes'". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

-

- "Austria's new government is a first—a Conservative-Green coalition". The Economist. 7 January 2020.

But on January 7th Mr Kogler, who led the party to a string of electoral successes last year, and three of his comrades were sworn in to government as junior partners to the right-wing Austrian People's Party (ÖVP).

- "Who's fired?". Financial Times. 30 September 2019.

His rightwing Austrian People's Party posted a projected 37 per cent in Sunday's general election, as both the Social Democrats and the far-right Freedom Party — Mr Kurz's allies in the government that collapsed in May — fell back.

- "Austrian MPs vote to ban headscarves in primary schools". euronews. 16 May 2019.

The law was tabled by the coalition government, made up of PM Sebastian Kurz' right-wing Austrian People's Party (ÖVP) and far-right Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ).

- "What's at stake in Austria's legislative elections?". TRT World. 24 September 2019.

That crisis—which saw the collapse of the coalition between the rightwing Austrian People’s Party (OVP) and the far-right Freedom Party of Austria (FPO)—stemmed from a controversial incident now known as the “Ibiza scandal”.

- "Austria's new government is a first—a Conservative-Green coalition". The Economist. 7 January 2020.

- "Austria election results: Far-right set to enter government as conservatives top poll". The Independent. 16 October 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- "Head of a state at 33 - meet the youngest serving leaders in the world". gulfnews.com.

- "Make Austria Great Again — the rapid rise of Sebastian Kurz". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- "The European Union's sanctions against Austria". WSWS. 22 February 2000. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- Donald G. McNeill (4 July 2000). "A Threat By Austria on Sanctions". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

Further reading

- Binder, Dieter A. (2004). Michael Gehler; Wolfram Kaiser (eds.). 'Rescuing the Christian Occident': The People's Party in Austria. Christian Democracy in Europe since 1945. Routledge. pp. 121–134. ISBN 0-7146-5662-3.

- Fallend, Franz (2004). Steven Van Hecke; Emmanuel Gerard (eds.). The Rejuvenation of an 'Old Party'? Christian Democracy in Austria. Christian Democratic Parties in Europe Since the End of the Cold War. Leuven University Press. pp. 79–104. ISBN 90-5867-377-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Austrian People's Party. |

- Official website

- Austrian People's Party Country Studies

- Austrian People's Party at the European People's Party website