Christian Social Party (Austria)

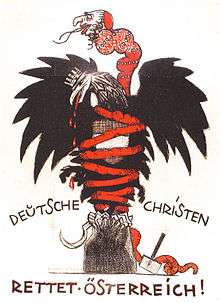

The Christian Social Party (German: Christlichsoziale Partei, CS) was a major conservative political party in the Cisleithanian crown lands of Austria-Hungary and in the First Republic of Austria, from 1891 to 1934. The party was also affiliated with Austrian nationalism that sought to keep Catholic Austria out of the state of Germany founded in 1871, that it viewed as Protestant Prussian-dominated, and identified Austrians on the basis of their predominantly Catholic religious identity as opposed to the predominantly Protestant religious identity of the Prussians.[2] It is a predecessor of the contemporary Austrian People's Party.

Christian Social Party Christlichsoziale Partei | |

|---|---|

| Leader | Karl Lueger (1893–1910) Aloys of Liechtenstein (1910–1918) Johann Nepomuk Hauser (1918–1920) Leopold Kunschak (1920–1921) Ignaz Seipel (1921–1930) Carl Vaugoin (1930–1934) Emmerich Czermak (1934) |

| Founder | Karl Lueger |

| Founded | 1891 |

| Dissolved | 1934 |

| Merged into | Fatherland Front |

| Headquarters | Vienna |

| Ideology | Conservatism[1] Political Catholicism[1] Austrian nationalism[2] Anti-Semitism[3][4] Right-wing populism[3] Corporatism[1] |

| Political position | Right-wing[5] |

| Religion | Catholic |

History

Foundation

.jpg)

The party emerged in the run-up to the 1891 Imperial Council (Reichsrat) elections under the populist Vienna politician Karl Lueger (1844–1910). Referring to ideas developed by the Christian Social movement under Karl von Vogelsang (1818–1890) and the Christian Social Club of Workers, it was oriented towards the petit bourgeoisie[6] and clerical-Catholic; there were many priests in the party, including the later Austrian chancellor Ignaz Seipel, which attracted many votes from the tradition-bound rural population. As a social conservative counterweight to the "godless" Social Democrats, the party gained mass support through Luegers anti-liberal and antisemite slogans. Its support of the Austro-Hungarian cohesion and the ruling House of Habsburg also gave it considerable popularity among the noble class, making it an early example of a big tent party.

Upon the implementation of universal suffrage (for men) under minister-president Max Wladimir von Beck, the CS gained plurality in the 1907 Reichsrat elections, becoming the largest parliamentary group in the Lower House; however already in the 1911 elections, it lost this position to the Social Democratic Workers' Party (SDAP). Though Minister-president Karl von Stürgkh had ignored the discretionary competence of the parliament during the 1914 July Crisis, the Christian Social Party backed the Austrian government during World War I. Nevertheless, when upon the dissolution of the Monarchy in October 1918 the German-speaking Reichsrat representatives met in a "provisional national assembly", the 65 CS deputies voted for the creation of the Republic of German-Austria and its accession to Weimar Germany, though shortly after members of the party began to oppose German annexation.[7]

First Republic

After the 1918 assembly had elected the Social Democrat Karl Renner state chancellor, the Christian Social Party formed a grand coalition with the SDAP under Karl Seitz. In the 1919 Austrian Constitutional Assembly election, the CS gained 35.9% of the votes cast, making it again the second strongest party after the Social Democrats. With its support the assembly enacted the Habsburg Law concerning the expulsion and the takeover of the assets of the House Habsburg-Lorraine. On 10 September 1919, Chancellor Karl Renner had to sign the Treaty of Saint-Germain, which prohibited any affiliation with Germany. It was ratified by the assembly on 21 October.

However, the next year the coalition broke up and Renner resigned on 11 July 1920, succeeded by the Christian Social politician Michael Mayr. Both parties agreed on scheduling new elections and the national assembly dissolved after it had passed the Constitution of Austria on 1 October 1920. Upon the following 1920 election, the CS gained 41.8% of the votes cast surpassing the Social Democrats and as the strongest party entered into a right-wing coalition with the newly established nationalist Greater German People's Party (GDVP). The National Council parliament, successor of the national assembly, re-elected Mayr chancellor in November 1920. The CS also nominated the non-partisan Michael Hainisch, actually a Greater German sympathizer, for Austrian president, who was elected by the Federal Assembly on 9 December.

All Chancellors of the First Austrian Republic from 1920 onwards were members of the Christian Social Party, and so was President Wilhelm Miklas, who succeeded Hainisch in 1928. The Social Democrats remained in opposition and concentrated on their Red Vienna stronghold, while the Austrian political climate polarized over the next years.

Chancellor Mayr had to resign as chancellor in 1922, after the Greater German People's Party left the coalition in disagreement over a treaty signed with the Czechoslovak republic concerning the Sudeten German territories. He was succeeded by Ignaz Seipel, CS chairmen since 1921. Seipel, a devout Catholic and fierce opponent of the Social Democrats, was able to re-arrange the coalition with the GDVP and was elected chancellor on 31 May 1922. From 1929 onwards, the party tried to form an alliance with the Heimwehr movement. Because of the instability of this coalition the party leadership decided to reform a coalition with the agrarian Landbund.

Patriotic Front

In the process of establishing the so-called Austro-fascist dictatorship, Christian Social Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuß founded the Patriotic Front (Vaterländische Front) on 20 May 1933, merging the CS with the Landbund, Heimwehr and other conservative groups. The party was finally dissolved with the entry into force of the "May Constitution" of 1934, the foundation of the Federal State of Austria.

With the assumption of chancellorship by the Nazi politician Arthur Seyss-Inquart and the succeeding Anschluss of Austria to Nazi Germany in March 1938, the Patriotic Front was banned and ceased to exist. After World War II, the party was not refounded. Most of the surviving CS supporters and politicians thought the name had become closely associated with Austrofascism; they founded the centre-right Austrian People's Party (ÖVP), which can be regarded as the linear successor of the CS.

Chairmen

| Chairperson | Period |

|---|---|

| Karl Lueger | 1893–1910 |

| Prince Louis of Liechtenstein | 1910–1918 |

| Johann Nepomuk Hauser | 1918–1920 |

| Leopold Kunschak | 1920–1921 |

| Ignaz Seipel | 1921–1930 |

| Carl Vaugoin | 1930–1934 |

| Emmerich Czermak | 1934 |

Notable members

Prominent members of the CS included:

- Karl Buresch

- Engelbert Dollfuß

- Otto Ender

- Viktor Kienböck

- Karl Lueger

- Michael Mayr

- Julius Raab

- Rudolf Ramek

- Richard Schmitz

- Kurt von Schuschnigg

- Ignaz Seipel

- Fanny von Starhemberg

- Ernst Streeruwitz

- Josef Strobach

- Carl Vaugoin

- Richard Weiskirchner

Literature

- Boyer, John W. (1981). Political Radicalism in Late Imperial Vienna: Origins of the Christian Social Movement, 1848–1897. University of Chicago Press.

- Boyer, John W. (1995). Culture and Political Crisis in Vienna: Christian Socialism in Power, 1897–1918. University of Chicago Press.

- Lewis, Jill (1990). Conservatives and fascists in Austria, 1918–34. Fascists and Conservatives: The Radical Right and the Establishment in Twentieth-century Europe. Unwin Hymen. pp. 98–117.

- Nautz, Jürgen (2006). Domenico, Roy P.; Hanley, Mark Y. (eds.). Christian Social Party (Austria). Encyclopedia of Modern Christian Politics. 1. Greenwood. pp. 133–134.

- Suppanz, Werner (2005). Levy, Richard S. (ed.). Christian Social Party (Austria). Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution. 1. ABC-CLIO. pp. 118–119.

- Wohnout, Helmut (2004). Kaiser, Wolfram; Wohnout, Helmut (eds.). Middle-class Governmental Party and Secular Arm of the Catholic Church: The Christian Socials in Austria. Political Catholicism in Europe 1918–45. Routledge. pp. 141–159. ISBN 0-7146-5650-X.

Notes and references

- Lewis, Jill (1990), Conservatives and fascists in Austria, 1918–34, pp. 102–103

- Spohn, Willfried (2005), "Austria: From Habsburg Empire to a Small Nation in Europe", Entangled Identities: Nations and Europe, Ashgate, p. 61

- Payne, Stanley G. (1995), A History of Fascism, 1914–1945, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, p. 58

- Pauley, Bruce F. (1992), From Prejudice to Persecution: A History of Austrian Anti-Semitism, University of North Carolina Press, pp. 156–158

- Romsics, Gergely (2010). The Memory of the Habsburg Empire in German, Austrian, and Hungarian Right-wing Historiography and Political Thinking, 1918–1941. Social Science Monographs. p. 211.

- Loewenberg, Peter (2009), "Austria 1918: Coming to Terms with the National Trauma of Defeat and Fragmentation", Österreich 1918 und die Folgen, Vienna: Böhlau, p. 20

- DIVIDE ON GERMAN AUSTRIA. – Centrists Favor Union, but Strong Influences Oppose It., The New York Times, 17 January 1919 (PDF)

- This article includes information translated from the German-language Wikipedia article de:Christlichsoziale Partei (Österreich).

- Franz Martin Schindler: Die soziale Frage der Gegenwart, vom Standpunkte des Christentums, Verlag der Buchhandlung der Reichspost Opitz Nachfolger, Wien 1905, 191 S.

External links

![]()

- (in German) Karl von Vogelsang-Institut Institute for the research of the history of Austrian Christian Democracy