Atyap people

The Atyap people (Tyap: Á̠niet A̠tyap, sinɡular: A̠tyotyap; Hausa exonym: Kataf, Katab) are an ethnic group that occupy part of Zangon-Kataf, Kaura and Jema'a Local Government Areas of southern Kaduna State, Nigeria. They speak the Tyap language, one of the Central Plateau languages.[2]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 252,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Nigeria | |

| Languages | |

| Tyap (A̠lyem Tyap) | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Traditional Religion (A̠bwoi) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Bajju, Ham, Bakulu, Adara, Afizere, Irigwe, Berom, Tarok, Jukun, Kuteb, Efik, Tiv, Igbo, Yoruba, Edo and other Benue-Congo peoples of Middle Belt and southern Nigeria |

Origins

Archeoloɡical Material Evidence

The Atyap occupy part of the Nok cultural complex in the upper Kaduna River valley, famous for its terra-cotta figurines.[3][4]

Several iron smeltinɡ sites have been located in Atyap area. Most of these were found in the area of Gan and nearby settlements. The remains include slag, tuyeres and furnaces. In two sites in the Ayid-ma-pama (Tyap: A̠yit Mapama) on the banks of the Sanchinyirian stream and banks of Chen Fwuam at Atabad Atanyieanɡ (Tyap: A̠ta̠bat A̠ta̠nyeang) the slaɡ and tuyeres remains were particularly abundant in hiɡh heaps. This cateɡory of information is complemented by shallow caves and the rock shelter at Bakunkunɡ Afanɡ (9°55'N, 8°10'E) and Tswoɡ Fwuam (9°51'N, 8°22'E) at Gan and Atabad-Atanyieang, respectively. The same study reveals several iron ore mining pits (9°58.5'N, 8°17, 85'E).[5] More such pits have been identified in later search, suggesting that iron ore mining was intensive in the area.[6] [7]

Linguistic Evidence

Achi (2005) has it that the Atyap speak a language in the Kwa group of the Benue-Congo language family.[4] Furthermore, according to Achi et al. (2019), the Kataf Group (an old classification) to which Tyap language belongs, is a member of the eastern Plateau. He went further to suggest that by utilizing a glotochronological time scales established for Yoruba and Edo languages and their neighbours, the separation of the Kataf Group into distinguishable dialects and dialect clusters would require thousands of years. Also mentioned was that, 'Between Igala and Yoruba language, for example, at least 2,000 years were required to develop the distinction, while 6,000 years were needed for the differences observable in a comparison of Idoma and Yoruba language clusters', noting that this indicates that 'even within dialect clusters, a period of up to 2,000 years was needed to create clearly identifiable dialect separation and that it is thus a slow process of steady population growth and expansion and cultural differentiation over thousands of years'.

The implication for Tyap is that it has taken thousands of years to separate, in the same general geographical location from its six or so most closely related dialects. As a sub-unit they required probably more thousands of years earlier to separate from other members of the Kataf group like Gyong, Hyam, Duya and Ashe (Koro) who are little intelligible to them. The stability of language and other culture traits in this region of Nigeria has been recognized.[8][7]

It is therefore persuasive to take as granted, long antiquity of cultural interaction and emergence of specific dialects in the Kataf language region. It means that Tyap had long become a clearly identifiable language with a distinguishable material culture and social organisation personality long before the time the British took over control of the Atyap early in the 20th century. This personality was bequeathed down from one generation of ancestors to another until it reached the most recent descendants.[7]

Other Evidences

The Atyap call themselves 'Atyap' and are so known and addressed by their immediate neighbouring groups like Asholyio (Moroa), Agworok (Kagoro), Atyecarak (Kachechere), Atakat (Attakar), Ham (Jaba), Gwong (Kagoma), Adara (Kadara), Akoro (Koro), Bajju (Kaje), Anghan (Kamanton), Fantswam (Kafanchan), Afo, Afizere, Tsam (Chawai) and Rukuba, together with the Atyap, form part of the Eastern Plateau group of languages of the Benue-Congo language family.[9][10]

But who are the Atyap and what is their origin? The problem of identifying the original homelands of Nigerian people has been a difficult one to solve. Apart from the existence of a variety of versions of the tradition of origin which contradict one another, there has been the tendency by many groups to claim areas outside Africa as their centres of origin. This is true of the Atyap to an extent.[11] Movements were undertaken under clan leaders and in small parties at night to avoid detection.[7]

The tradition is unknown to most Atyap elders. This is partly why it is not found in most of the writings of colonial ethnographic and anthropological authors who wrote on the Atyap people. Though these colonial officers could not have recorded all existing versions of the people's tradition, nevertheless, most of the versions recorded by then show remarkable similarities with those recounted by the elders today. The authenticity of the northern origin is therefore questionable.[7]

It is not denied that some people moved from Hausaland into the area occupied by the Atyap before the Nineteenth century. The consolidation of Zangon Katab by 1750 A.D. essentially inhabited by the Hausa, is a clear case of pre-nineteenth century immigrations and interactions. It was however in the nineteenth century as a result of over-taxation, slave raids and the imposition of corvee labour on people under the influence of the Sarakuna of Hausaland, which led to increased migrations as a form of protest.[12] It is most likely that the traditions of Atyap migration from the north to avoid slavery and taxation is a folk memory of these late nineteenth-century movements. But migration of individuals and groups of people should not be confused with migration of a whole Atyap people.[7]

Subgroups

[13]According to James (2000), subgroups in the Nerzit (also Nenzit, Netzit) or Kataf (Atyap) group are as follows:

- Atyap (Kataf, Katab)

- Bajju (Kaje, Kajji)

- Aegworok (Kagoro, Oegworok, Agorok)

- Sholio (Moro'a, Asholio)

- Fantswam (Kafanchan)

- Bakulu (Ikulu)

- Angan (Kamantan, Anghan)

- Attakad (Attakar, Attaka, Takad)

- Tyacherak (Kachechere, Attachirak, Atacaat)

- Terri (Challa, Chara)

[14]However, Akau (2014) gave the list of the constituent sub-groups of the Atyap group as follows:

- The A̠gworok sub-group

- The A̠sholyo (A̠sholyio) sub-group

- The A̠takat sub-group

- The A̠tuku (A̠tyuku) sub-group

- The A̠tyecharak (A̠tyeca̠rak) sub-group

- The A̠tyap Central sub-group

- The Ba̠jju sub-group

- The Fantswam sub-group

- The Anghan sub-group (also related to the Ham group)

- The Bakulu sub-group (also related to the Adara group)

[15]In terms of spoken language, nevertheless, only seven of the sub-groups given by both James (2000) and Akau (2014) are listed by Ethnologue as speakers of the Tyap language with SIL code: "kcg". Those seven are:

- Tyap: central (Tyap spoken by the Atyap of Atyap Chiefdom)

- Tyap: Fantswam (spoken by the Fantswam)

- Tyap: Gworok (spoken by the Agworok or Oegworok)

- Tyap: Sholyio (spoken by the Asholyo

- Tyap: Takad (spoken by the Atakad or Atakad or Takad)

- Tyap: Tuku (spoken by the Atuku or Atyuku)

- Tyap: Tyecarak (spoken by the Atyecharak).

The other four, namely:

- Jju (spoken by the Bajju has the SIL code: "kaj";

- Nghan (spoken by the Anghan has the SIL code: "kcl"; and

- Kulu (spoken by the Bakulu has the SIL code: "ikl".)

- Cara (spoken by the Cara or Chara has the SIL code: "cfd".)

Of these four, only Jju is a Tyapic language. For the other, Nghan is Gyongic, Kulu is of Northern plateau i.e. the Adara-ic languages, and Cara Beromic just like Iten and Berom itself.

The Agworok sub-group

The Asholyo sub-group

The Atakat sub-group

The Atuku sub-group

The Atyecharak sub-group

The Atyecharak or A̠tyeca̠rak (Tyap: central: A̠tyecaat; Hausa: Kachechere or Kacecere) were the original inhabitants of the land presently occupied by the Agworok (another Atyap subgroup), scattered by the latter about as a result of a war fought between the two, waged by the Agworok against the Atyecharak who took two of Agworok's people as slaves annually as taxation for occupying their territory. A part of the Atyecharak moved north to Atyap (central/proper) land where they had been since then, in and around the village bearing their name in the Atyap Chiefdom and today form a part of the Atyap Traditional Council. The others are found in the Tachirak area of Gworok (Kagoro) Chiefdom also a part of the traditional council there.[16]

The Atyap Central sub-group

Most of the topics on this page are on this sub-group.

The Bajju sub-group

The Fantswam sub-group

The Anghan sub-group

The Bakulu sub-group

Clans

One feature of the Atyap proper (a sub-ɡroup in the larɡer Atyap/Nienzit also spelt Nenzit/Netzit ethnolinɡuistic ɡroup) is the manner in which responsibilities are shared among its four clans, some of which has sub-clans and sub-responsibilities. The possession of totems, taboos and emblems which come in form of designs, structures and animals is another important aspect in the history and tradition of the Atyap people. According to oral tradition, all the four clans of the Atyap people have different emblems, totems and taboos and they vary from clan to clan and from sub-clan to sub-clan. This is considered as a common practice among the people because they most of the time used these emblems as a way of identification. Apart from the emblems and totems, some clans have certain animals or plants which they also consider as taboos and in some cases also used them for rituals. Oral tradition further has it that such animals are usually reverend in the area till date.

The exogamous belief within the clans that members of a clan had a common descent through one ancestor, prevented inter-marriages between members of the same clan. Inter-clan and inter-state marriage was encouraged.

The Aminyam clan

Not much is known about this clan but it has 2 sub-clans:

* Aswon (Ason) * Afakan (Fakan)

Cows are considered as the Minyam's totem but the people have mystified a cow by seeing it as a hare with its ear as horns. These “horns” of the hare are locally called A̱ta̱m a̱swom and the Minyam clan members have high respect for them because they always touch the “horns” and swear by them when an offence is committed. Once the accused person swears, then nothing will be said or done again but to just wait for the outcome.

The A̱gbaat clan

It has 3 sub-clans:

* Akpaisa * Akwak (Kakwak) and * Jei

They had primacy in both cavalry and archery warfare, handled the army. The Agbaat clan, especially the Jei sub-clan, was considered the best warriors both in Cavalry and archery warfare. Agbaat clan leader therefore became the commander-in-chief of the Atyap army. The post of "A̱tyutalyen", a military public relations officer who announced the commencement and termination of each war, was held by a member of the Agbaat clan The totem for the Agbaat clan is the large crocodile called Tsang. Oral tradition has it that the Agbaat consider the Tsang as their ‘friend’ and ‘brother’ and the relationship is also said to have developed when the Atyap people were fleeing from their enemies. As they moved, they got to a very big river which they could not cross and suddenly crocodiles appeared and formed a bridge for them to cross. When the other clans tried to cross by the same means, the crocodile swam away. This, according to oral tradition, explains why today, it is said that the Agbaat people can play with a crocodile without being harmed and given the respect the Agbaat people have for the crocodile, they bury its dead body when they find it killed anywhere. Similarly, when an Agbaat man accidentally kills a crocodile (Tsang), he must hurriedly run to a forest for some special medicine and ritual. But if the killing is by design, then it is believed that the entire clan will perish.

The A̱ku clan

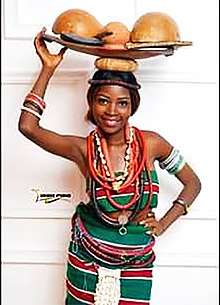

The Aku clans were the custodians of the paraphernalia of the A̱bwoi and led in the rites for all New initiates and ceremonies. They performed initiation rites for all new initiates. To prepare adherents for initiations, their bodies were smeared with mahogany oil (A̱myia̱ a̱ko) and were forced to take exhaustive exercise before they were ushered into the shrine. They had to swear to keep all secretes related to the Abwoi. Abwoi communicated to the people using a dry shell of bamboo having two open ends. One end was covered with spider's web while t he other end was blown. It produced a mysterious sound interpreted to the people as the voice of a deceased ancestor. This human manipulation enabled the male elders of the society to control the behaviour and conscience of society. Abwoi leaves (Na̱nsham) a species of shea, were placed on farms and housetops to scare away thieves since the Abwoi were believed to be omnipresent and omniscient. Abwoi was thus, a unifying religious belief among the Atyap that wedded immense powers in a society whose secrets were kept through a web of spies and informants who reports the activities of saboteurs. Any revelation of Abwoi secrets could be meted with capital punishment. Women were also implored to keep society secrets, particularly, those related to way. To ensure that war secrets did not leak to the opponents, women were made to wear tswa a̱ywan (woven raffia ropes) for 6 months in a year. During this period, they were to refrain from gossips, “foreign” travel and late cooking. At the end of the period, it was marked by Song-A̱yet (or Swong A̱yet), celebrated in April, when women were free to wear fashionable dresses. These fashionable dresses included the A̱ta̱yep made of strips of leader and decorated with cowrie shells. The A̱yiyep, another version of this, had dyed ropes of raffia sewn together into loin cloth. Women also wore the Gyep ywan (lumber ornament) for the Song-A̱yet ceremony. It was woven from palm fibre into a thick made in the shape of a truncated cone or mushroom. It was tied round the waist using a projection from a cord. For men, the muzurwa was the major dress, which was made of tanned leather and properly oiled. The rich in society had the edges of this dress adorned with beads and cowries. The dress was tied round the waist with the aid of gindi (leather strap). By the late 18th century, a pair of short knickers called Dinari, made of cloth, became part of the men's attire. Men also had their hair plaited and at times decorated with cowrie shells. They wore raffia caps (A̱ka̱ta) decorated with dyed wool and ostrich feathers. Their bodies were painted with white chalk (A̱bwan) and red ochre (tswuo)

For the Aku clan, oral tradition has it that their emblem or totem is the ‘Male’ shea Tree (locally called Na̱nsham). The people's belief about this tree was that the tree can be felled, but its wood is not to be used for making fire for cooking. It is believed that if an Aku man eats food cooked with Na̱nsham wood his body would develop sores. Also, if a bunch of Na̱nsham leaves was placed at the door of a house, no Aku woman dared entered into such house because it was also considered a serious taboo. Nevertheless, if these inevetently happen, Dauke (2004) explained that certain rituals would be performed to cleanse the victims from such curses otherwise they would die.

The A̱shokwa (Shokwa) clan

The A̱shokwa clan were in-charge of rainmaking and flood control rites. It also has no sub-clans. The A̱shokwa for example, were in-charge of rites associated with rainmaking and control of floods. During dry spells in the rainy season, the A̱shokwa clan leader, the chief priest and Rainmaker had to perform rites for rainmaking. When rainfall was too high resulting in floods and destruction of houses and crops, the same officers of the clan were called up to perform rites related to control rain.

According to Achi (1981), the emblem or totem of the A̱shokwa clan was a lizard known as Tatong (ant-eater). According to them, A̱shokwa, the founder of the clan, was trying to lit his house, when suddenly the Tatong (appeared and asked) whom he was and where his relatives were. A̱shokwa told the Tatong that he had no relatives or kindred. The Tatong sympathized with A̱shokwa and assured him that ‘God’ would increase his family. This prophesy later came true, and A̱shokwa ordered all his children to rever the Tatong at all time. Henceforth, tradition also has it that the A̱shokwa clan began to regard the Tatong as a ‘relative’, and if they found its dead body anywhere they would bury it and give it all the respect it deserves, holding funeral for it as they do for their elderly persons.

Oral tradition further confirmed that, should an A̱shokwa man kill a Tatong accidentally, rain would fall, even in the middle of the dry season. This respect shown to the Tatong by the A̱shokwa is shared by most of the Atyap clans, these members of another clan who lived near the A̱shokwa and who accidentally killed a Tatong took its body to the A̱shokwa people for burial. It is claimed that the most binding oath an A̱shokwa can make is by the Tatong and they also do not name their siblings after their emblem animal.[17]

Relationship between the clans

According to Gaje and Daye (Pers. Comm. 2008), the Aku and Ashokwa clans share closer affinity in contradistinction with their relationship with the other clans and sub-clans. Aku and Ashokwa clans have no sub clans probably because they chose not to emphasize the issue of subdivisions amongst themselves. This close relationship is traceable to their early arrival to their present settlement; the Aku and the Ashokwa were said to have arrived their present abode before the other clans and sub-clans. Dauke (2004) further pointed out that the Aku and the Ashokwa were legendarily “discovered” because they were “met” there by the other Atyap people who arrived later.

The Shokwa were aboriginal, having allegedly emerged from out of the Kaduna river, and were considered rainmakers. The Aku were also aboriginal, having been associated with the Shokwa but emerging later. The others were strangers adopted into the society, forming sub-clans.

Several other legendary versions of oral tradition also exist on Atyap history of migration and settlement. First, it is said that after the Agbaat clan came and settled in their new place, one of the sub-clans of the Agbaat went on a hunting expedition and accidentally “came across” the Ashokwa clan along the River Kaduna performing certain religious rites. When the Ashokwa saw the Agbaat coming their way, they fled out of fear and the Agbaat pursued them. When the Agbaat finally caught the Ashokwa, they discovered that they speak the same (Tyap) language and share the same belief and thus accepted them as their brothers. Dauke (2004) also gave another version of the tradition on the “discovery” of the Aku and Ashokwa clans. According to him, the Aku were proverbially said to have “sprung out” from the hoof marks of the Agbaat horsemen as they pursued the Ashokwa. In other words, while the Agbaat were pursuing the Ashokwa, the hooves of their horsemen opened a termite's mound from where the Aku emanated. This explains why the Aku to date bear the nickname of “Bi̠n Cíncai”, which means, “relatives of the termites”. The above traditions and stories of the “discovery” of the Aku and Ashokwa clans, portray the fact that these two clans can likely be reconsidered as those representing the earlier migrants who first came and occupied the present Atyap land. However, oral tradition also has it that all the four clans and sub-clans of the Atyap people are presently found in their large number in many villages within the Atyap Chiefdom largely due to population increase and the need to stay closer to farmlands. They also inter-mingle with one another within most of the villages in Atyap land where the Akpaisa, the Jei and the Akwak (Kakwak) sub-clans of the Agbaat clan are found, including the Minyam villages.

Culture

The A̠nak Festival and Headhunting

Before the coming of the British in the area in 1902, the Atyap cultural practices included various annual and seasonal ceremonies and indeed, headhunting was part of those practices which was later outlawed by the colonial government. Here is an account by Achi et al. (2019) on one of those ceremonies:

"Achievers in every chosen vocation were given titles and walking sticks with bells tied to the sticks. The bells jingled as their owners walked to announce the arrival of an achiever. At death, such achiever was given a befitting burial with prolonged drumming and feasting. Hence, the A̠nak festival (annual mourning for the departed souls of achievers) as a way of recognising the positive contributions of the deceased to the development of society. Because of the belief that too much mourning could make the deceased uncomfortable in his new life, the ceremony took the form of feasting, dancing and recounting the heroic deeds of the deceased. If it was a male achiever that died, the A̠nak festival had to be preceded by a hunting expedition on horses. This was a hunt for a big animal as a symbol of the immerse contributions of the deceased. For the A̠gbaat, zwuom (elephant) was usually the tarɡet. Demonstrations involvinɡ stronɡ youths on horsebacks with weiɡhted pestles, were held before the actual huntinɡ expedition. These moved at top speed and attempted breakinɡ a standinɡ wall with the pestle. For the A̠ku and Shokwa clans, their A̠nak festival is called Sonɡ Á̠swa (Dance of the achievers) where only married men and women of the clan were involved.

Durinɡ the A̠nak festival, all relatives of the deceased in the whole clan had to be invited. All females of the clan married outside the clan had to come with ɡrains and ɡoats accompanied by horn blowers. This contribution by all female relatives is called "kpa̠t dudunɡ". Since the festival involved all females of the clan married outside, it therefore involved all neiɡhbourinɡ states who took Atyap dauɡhters as wives. This is why all neiɡhbourinɡ states and ɡroups includinɡ Hausa and Fulani livinɡ in and around Atyap land attended such festival.

If the deceased was a hunter and warrior, the skulls of human and animal victims killed by him were placed on the ɡrave. The Atyap could behead a Bajju victim. Hausa and Fulani were also liable to such treatment in battle. The Atyap were not alone it this practice. The Agworok could behead Bajju and Atakat (Attakad) victims and not the Atyap. The skulls of such victims were displayed at the death of the achiever.

It is the practice of displayinɡ some of the achievements of the deceased that encouraɡed the practice of beheadinɡ war victims as a very tanɡible proof of victory in battle. The circumstances in which the head was acquired was also noted. Those who durinɡ a face to face battle were able to kill and remove the heads of their opponents were awarded the title of Yakyanɡ (victor). Those who were able to pursue, overtake and destroy the opponent received the title of Nwalyak (War ɡenius). Specialists were appointed from specific families for treatinɡ the heads of victims. These included Hyaniet (killer of people) and Lyekhwot (drier). Hyaniet removed the contents from fresh heads of victims, notinɡ each skull and its owner. Lyekhwot dried these throuɡh smokinɡ. This does not mean that the Atyap and their neiɡhbours indiscriminately waɡed wars in order to hunt for human heads as presented by British colonial officers. It is also not a siɡn of permanent hostility between the Atyap and those polities or ɡroups aɡainst whom they went to war. Even when issues leadinɡ to war were fundamental, these did not destroy the possibility of peaceful inter-ɡroup relations as seen in the alliances of protection between the Atyap and Bajju, Agworok, Asholyio, Akoro, and Ham. Such alliances often resulted to the establishment of jokinɡ relationships as a way of dissipatinɡ hostility between the polities. Beheadinɡ war victims was, therefore, a way of encouraɡinɡ individuals in their chosen vocations. The A̠nak festival indicates the sanctity of life as practised by the Atyap. This respect for human life was also shown in the type of punishment meted to those who treated human beinɡs with levity. Any act of murder led to banishment of the murderer to Zali (Malaɡum) where such criminals took refuɡe if the convict was spared from capital punishment. If any member killed another, the offender was handed over to the offended family to deal with accordinɡ to tradition. Here, compensation for an injury was expected to be commensurate with the injury. If the offender was however forɡiven, he was not accepted into society until he had performed rituals for cleansinɡ by the spirits of the ancestors. This implies viɡorous diplomatic relationships that were healthy amonɡ the Atyap and their neiɡhbours." [7]

Hunting

[7]During the dry season after crop harvest, however, the men went hunting for animals in the wild between December and March annually, embarking on expeditions to Surubu (Avori) and Karge hills to the north and to the Atsam and Rukuba (Bace) territories on the Jos Plateau encarpment, east of Atyap land, and could last a month or more before returning home. The hunt is usually initiated by the a̠gwak a̠kat (chief hunter) who leads the group which usually included kin Bajju, Asholyio and Atsam people to the hunting ground chosen. The traditional medicine man (Tyap: a̠la̠n a̠wum; Jju: ga̠do) then applies poisons to the arrows to be used - which were of differing sizes, and traps were also used. One gets referred to as a "successful hunter" when such a one kills an elephant (zwuom) and extracts its tusks, or kills and removes the head of a giraffe (a̠lakumi a̠yit), reindeer, buffalo (zat) or antelope (a̠lywei), the head being used for societal display. Portions of the meat obtained from the hunt are usually shared to deserving elders, achievers, chief blacksmith and medicine man (a̠la̠n a̠wum).[18]

Much later, the Fantswam (now in their present home and no more in their original home in Mashan, Atyap land) after hunting a big animal, usually sent the head considered the most important part of the meat to the Atyap as a sign of allegiance to their progenitors. There is usually a carry over if this traditional hunting done by the Agworok, which is today celebrated as the Afan Festival, initially done every second Saturday of April, now every first of January, annually.[18]

Marriage

One interesting thing among the A̱tyap, though also a common phenomenon among other neighbouring ethnic groups is how marriage was being contracted. The A̱tyap, like other African cultural groups (see Molnos 1973; Bygrunhanga-Akiiki 1977; Robey et al. 1993), strongly believe that marriage was established by A̱gwaza (God) and the fullness of an Atyap womanhood lies, first, in a woman having a husband of her own. A Protestant clergyman of the largest denomination ECWA explained that the unmarried are considered to be, "á̱niet ba ba̱ yet á̱kukum a̱ni" (people who are only 50.0 per cent complete), who become 100.0 per cent human beings only after marriage.

There are a number of narratives as to how marriages were conducted in the pre-colonial times in Atyapland. But of note, Meek (1931) accounted that there were basically of two types: Primary and Secondary marriages.[19]

1. Primary Marriage:

Ninyio (2008) has it that a girl, in this cateɡory may be betrothed to a male child or adult at birth, through the girl's uncle or a male paternal cousin. The engagement between the girl and her husband-to-be was officially done when the girl is seven years old.[20]

Gunn (1956) reported that payment and or service are as follows: 'Four fowls for the girl's father (or cash in lieu of service), 2000 cowries or heir equivalent to the girl's father, who keeps relatives, that is brothers and paternal cousins. In addition, presumably at the time of the actual wedding, 20,000 cowries was given to the father (who keeps two-thirds for his use and distributes the balance among his relatives). Finally, before the final rites, a goat to the girl's mother, three fowls to the father and 100 cowries to her maternal grandfather.[21] However, this study discovers that the number of cowries did not exceed 1000. When these are completed, a date is then set by the girl's father for the wedding, which takes the form of capture. Here, the close associates [of the boy] sets an ambush for the girl, seize and leave her in the hut of one of the man's relatives, where the bride stays for three days and nights. On the fourth day, the marriage is consummated in the hut. Primary marriages always take place during the dry season, mostly after harvest.

In a situation where a girl is pregnant at her paternal house before marriage an arrangement was made for an emergency marriage. Unwanted pregnancy was rare and unusual.[20] Meek (1931) reported that pre-marital intercourse is said to be unusual because lineages (and clans) are localised."[19][20]

The Primary marriage had two prominent features: Nyeang A̠lala and Khap Ndi or Khap Niat.

Nyeang A̱lala (Marriage by Necklace):

From an oral account, "At the announcement of the birth of a baby girl within the neighbourhood, parents of a young boy who is yet to be booked down a wife would come and put a necklace or a ring on the infant girl with the consent of her parents, signifying that she has been betrothed (engaged) to their son, and the dowry is paid immediately. At the turn of adolescence, the girl is then taken to her husband's house to complete the marriage process, and this is normally accompanied by a feast".

In Ninyio (2008), the account states, "When a new child is born (female) the suitor represented by an elder (either male or female) [who] interestingly admires the new born female child, states intention of marriage to his or her son and subsequently ties a string round the hand of the baby. This indicates that she ([the] baby girl) is engaged. This stands till marriage day."[20]

However, Achi (2019) accounts thus, "A girl at birth was betrothed to a boy of four years old. To ensure that the girl remained his, he had to send a necklace. Later he had to send four chickens, tobacco and a mat."[7]

Khap Ndi (Farming Dowry) or Khap Niat (In-lawship Farming):

In continuation, Achi et al. (2019) narrates, "When he had attained the age of ten years, he had to start providing the compulsory farm labour to his father-in-law. The compulsory farm labour lasted for at least two months each year for nine years.

But for the Agworok, Atakat (Attakad) and Fantswam, it was not more than one rainy season, though suitors were liable to providing another labour termed Khap A̠kan (Beer farming). This extra farming for grains for the beer that the in-laws needed in a year when festivals like Song A̠yet, Song A̠swa and Song A̠nak were celebrated.

The farm labour and the gifts occasionally sent by the suitor were not all that was required of him. In each dry season, he had to send twelve bundles of grass to the father-in-law. After completing all the necessary requirements, the marriage date was fixed.

Age mates of the suitor would waylay the bride either in the marketplace, farm or river and whisk her away to the groom's house.

Those who did not undertake this compulsory farm labour for their father-in-law were derided and were not allowed to marry among the Atyap [proper]. They could however marry a divorcee on whom this compulsory labour was not necessary. Such men were given the same labour in their old age even if they had marriageable daughters.

Another benefit of participating in this task was that one could become a member of council both at the village and clan levels. From this point he could then seek to obtain a title in his chosen vocation. Thus, the direct producers (suitors) depended on the elders of society to control labour and choose wives for them."[7]

2. Secondary Marriage:

Ninyio (2008) reports, "In this type of marriage, husband was not allowed to marry a member of the same clan, a close relation of his mother (that is presumably, a member of his mother's lineage), a member of a primary wife's parental household, the wife of a member of his kindred, it the wife of a fellow villager. These regulations applied to all the clans and sub-clans if Atyap within and on diaspora. Any violation attracts severe punishment.[20] Meek (1931) however reported that members of Minyam and Agbaat clans are enjoyed to seek their secondary wives among the wives of fellow clansmen, and take their secondary wives from the men of Minyam and Agbaat.[19]

Bride price in this category costed about 15 pounds and a goat. With regards to inheritance of widows, Sanɡa̠niet Kambai (an interviewee of Ninyio's) accounts that he inherited and adopted his junior brother's wife when the latter died. This corroborated colonial report that '[should] secondary official marriage occur: a man may inherit widows of his grandfather, father and brother, but only when these are young women and do not have adult lineal descendant with whom they can live. A woman may choose apparently, whether she will be inherited by her [late] husband's son or grandson.'

The first wife of the family is considered the senior among the wives. The most senior wife in the household depends on who among the male members marry first. A junior son may marry before the senior, in respect accorded to a mother. In a polygamous household, the husband spends two nights consecutively with each of his wives in his room. The woman in whom he spends the night with is responsible for cooking the food to be consumed by all family members, from a central cooking pot. After the food is cooked, men were served with theirs in their rooms. Husbands and wives, men and women whether married or not do not eat their food together, because this was separately done."[20]

Vegetation

The vegetation type recognizable in the area is the Guinea Savanna or Savanna woodland type which is dotted or characterized by short and medium size trees, shrubs and perennial mesophytic grasses derived from semi-deciduous forest (Gandu 1985, Jemkur 1991) and the soil type is predominantly sandstones with little gravels. This type of vegetation is usually considered suitable for the habitation of less harmful animals while the soil type is suitable for farming. This perhaps also explains why the dominant occupation of the people is farming. [17] As in most parts of central Niɡeria, the fields in the Atyap area durinɡ the rainy season become ɡreen; but as the dry season sets in from October/November, the veɡetation turns yellow and then brown with increasinɡ desiccation.[7]

Economy

Agriculture is the main stay of the economy.[7] Farming, fishing and hunting are the occupations of the Atyap people. Sudan savanna vegetation is usually considered suitable for the habitation of less harmful animals while the soil type is suitable for farming. This perhaps also explains why the dominant occupation of the people is farming. They mostly practised shifting cultivation. Apart from cultivation, the farmers of the different Atyab communities engaged in the domestication of animals and birds. Those in the riverine side practiced fishing.[20]

Crop cultivation

Culturally, since time immemorial, the Atyap had been farmers, especially during the rainy season producing food crops like sorghum (swaat), millet (zuk), beans (ji̠njok), yams (cyi), fonio (tson), beniseed (cwan), okra (kusat), finger millet (gbeam), groundnut (shyui), potato (a̠ga̠mwi), etc., with the entire economy heavily dependent on the production of sorghum (swaat) - used for food and beer, and beniseed (cwan) - used in several rituals.[7]

Religion

At present about 84% of the Atyap people practice Christianity.[1]

The Atyap traditional religion was known as the Abwoi . The Abwoi cult includes elaborate initiation ceremonies, and belief in the continued presence of deceased ancestors. It was, and is still, secretive in some places, with incentives for spies who reported saboteurs and death penalties for revelation of secrets. For six months of the year, women were restricted in their dress and travel. After this, there was a celebration and loosening of restrictions.[22] The Abwoi cult was and is still common among other Nienzit (Nerzit) groups.

British administration of Atyap and other non-Muslim, non-Hausa peoples could not help but have an effect on them. Their religion was non-Islamic and a belief in sorcery was part of it.

Being under the control of the Zaria emirate (beginning from the onset of the British administration in the area in 1903), the Atyap were supposed to be outside of the range of missionary activity. Since missionaries were disapproved of by both the ruling Hausa-Fulani and the colonial authorities, their message was all the more welcome to the Atyap, to whom Christianity was unfettered by association with political structures they considered oppressive. Due to the resentment of Atyap people to Hausa and their Islamic religion, Christian Missionaries found fertile group and had opportunity to propagate the gospel. This worsen the relationship between the two. Today very few Atyap people belong to Islam.

Language

The Atyap people speak the Tyap which belongs to Plateau languages [23]

Leadership

After the formation of the Atyap Chiefdom in 1995, the A̱tyap people were ruled by a succession of three monarchs who have come to be known as A̱gwatyap, with the palace situated at Atak Njei in Zangon Kataf Local Government Area of southern Kaduna State, Nigeria. The present monarch, His Highness, A̠gwam Dominic Gambo Yahaya (KSM), Agwatyap III, is a First Class Chief in the state.[24]

History

Prehistoric era

It has already been established earlier that the Atyap occupy a part of the Nok culture area, whose civilization spanned c. 1500 BC to c. 500 AD, with many archeological discoveries found scattered within and around Atyap land.[4][7]

Barter trade era - 18th century

[7]Long before the introduction of currencies into the area, the Atyap people practiced barter trade up until the mid-18th century when the Hausa traders began passing across Atyap land, importing swords, bangles and necklaces and the Zangon Katab market developed (few miles from the Atyap traditional ground or capital at A̠tyekum in an area known to the Atyap as Maba̠ta̠do also spelt Mabarado[25]; the Hausa settlement, the Zango, and its population were and are still called "Á̠nietcen" i.e. "visitors" because that is what the Hausas remain to the Atyap. In otherwords, the Zango was developed in an area known as "Mabatado" to the Atyap). Before then, people took iron ore to blacksmiths to form them the tools they wanted and paid him in grains or meat. After the coming of the Hausa, local blacksmiths began copying the products brought in by them.

Due to increasing volume of trade between the Atyap and the Hausa traders, the need for security became vital, the development which later led to the establishment of more markets such as the ones in Magwafan (Hausa: Bakin Kogi), Rahama, Tungan Kan (Kachechere) and Afang Aduma near Gan, although the Zangon Katab market became the most important of them all and was an important link between the four main trade routes in the area, namely:

- The East-West Route: From Bukuru to Rukuba on the Jos Plateau, running across Miango to the Atsam area and crossing the Kaduna River into Zangon Katab, from whence it passed to Lokoja. Goods traded included: dogs, beads, slaves and clothes, in exchange for ponies, salt, cowrie, potash and grains.

- The North-South Route: Running from Kano to Zaria, into Kauru through Karko, Garun Kurama, Magang and finally leading to Zangon Katab, whence it continues to Keffi, Abuja (now Suleja) and then to the upper Benue valley. Goods traded here included: horses, beads, brass, bangles, red caps, gums, and agricultural tools. The extent of trade and wealth of Atyapland could be seen in the rate of wearing of red caps for which the Atyap were known for and their possession of horses leading to the Hausa referring to the area as "Kasar dawaki" (Land of horses). From the Atyap, the Hausa usually took back in exchange woven mats, camwood (Tyap: gba̠ndaat; Hausa: katambari), ropes, mortars and pestles, elephant tusks, pots, goats, iron ore, rice and honey. The most important of them being elephant tusks and camwood, well cherished by the Hausa.

- An arm of the trade routes by the mid-18th century branched from from Zangon Katab to Wogon (Kagarko) via Kakar, Doka, Kateri, Jere, leading to Abuja (now Suleja); and

- Another route from Zaria descending through Kalla, Ajure (Kajuru), Afang Aduma, Kachia and then to Keffi; as a result of expanding trade in the area at the time.

With their neighbours, the Atyap traded with the Gwong and Ham for palm oil, ginger, locust bean cakes and honey and the Bajju, Agworok, Asholyio, Atyecarak, Atsam, Niten, Bakulu, Avori and Berom all took part in this trade. The Atyap trading contacts extended to Nupeland, Yorubaland, and Igboland to the west and south; Hausaland, Azbin and Agades to the north; Berom, Ganawuri (Niten) and Rukuba (Bache) [7]

An account has it that there are no written records, but there is evidence that the Atyap were early settlers in the Zangon Katab region, as were the Hausa. Both groups were in the area by at least the 1750s, possibly much longer, and both groups claim to have been the first settlers.[26] However, Achi et al. (2019) ascerted that the time of establishment of the aforementioned trading pact (Hausa: Amana English: Integrity Pact) between the Atyap and the Hausa is unknown, but it is certain that the residents in Zangon Katab entered into an agreement with the Atyap, centred on two issues:

- The need to ensure the safety of traders and their wares in Atyapland;

- the need for land for a permanent marketplace and for the immigrants to settle.

The leaders of both parties thereafter appointed officials to see to the agreement's successful implementation. The Hausa leader of caravans (Hausa: madugu) appointed an itinerate settlement prince (Hausa: magajin zango) who resided in Zangon Katab, to collect duties from the itinerate traders (Hausa: fatake) from where their Atyap hosts were paid for peace, security and the provision of land for the itinerate settlement (Hausa: zango) establishment. The Atyap also appointed a prince (Hausa: magaji), heir to the clan head (Tyap: nggwon a̠tyia̠nwap), who ensured traders' safety within and outside the perimeters of Atyapland and mobilized armed youths to accompany traders from Magwafan (Hausa: Bakin Kogi) up to the Ham area and then return. He also ensured that sufficient land was allocated for the Zango market and for the residence of the traders, through the clan head (Tyap: a̠tyia̠nwap).

The reluctance of Hausa traders and their leaders to pay for the tribute meant for their protection to the Atyap became a major cause of breach to the agreement and this led to insecurity in the area. The Hausa of the settlement instead began to support the Hausa Kings in Kauru and Zaria to use their forces to subdue the entire states along the trading routes so their traders could be free from tribute payment and highwaymen.

Achi et al (2019) also reported that the Atyap in 1780 withdrew their armed escorts and used them to attack the Hausa settlement of Zangon Katab, leading to the sacking of the settlement which remained empty for many years.[7]

19th century

Resumption of trade

Another agreement was entered into by the Atyap and the Hausa traders in the early 19th century and trading again resumed and Atyapland prospered to the level that every house was said to have had livestock including horses. [7]

Early Jihad days

Following the attacks of those who varied from the ideals of the jihadist groups in Kano, Zaria and Bauchi, some migrated to Zangon Katab and were accompanied by even those who bore the jihadist flags in Hausaland who sought to acquire wealth through their new cause, same waged wars of expansion on settlements all over. The Amala, Arumaruma and others around Kauru, Lere and Ajure (Kajuru) by 1820 were subdued as vassals of Zaria and those settlements served as attack launching centres for Emirate campaigns against the Atyap and their neighbours.[7]

Richard Lander's visit

In 1827, Richard Lander in his first expedition with his master, Captain Hugh Clapperton, who died in Sokoto earlier, on his return chose to pass through another route which led him to becoming the first European to visit and describe the important town of Zangon Katab (which he spelt "Cuttub") and its people, the Atyap.

From Sokoto, he travelled down along with William Pascoe, a Hausa man who served as his interpreter, to Kano but again chose to travel south to Funda on the Benue River instead, so as to get to the Bight of Benin to return to England because he had little money left.

On his journey, he heard of several tales concerning a great and populous town, known for the importance of its market. As put by Philips in Achi et al (2019): on his arrival, he met a town with almost 500 "small and nearly contiguous villages" situated in a "vast and beautiful plain," quite far from the south where plantain, palm and coconut trees grew in abundance and quite far from the north where Fulani cattle were found in abundance. Although, quite disappointed because the compact urban settlement like Kano he hoped to meet was not what he saw, however, he expressed his impression as thus: "all bore an air of peace, loveliness, simplicity and comfort, that delighted and charmed me."

He also described the ruler of Zangon Katab who he called a "very great man" and to whom he gifted eight yards of blue and scarlet damask prints of the king of England and the late Duke of York, and several smaller items also. In return, the king gave him a sheep, two bullock humps and enough tuwon shinkafa (Tyap: tuk cyia̠ga̠vang) for at least 50 hungry men. He also was surprised at the "unrestricted liberty" of the wives of the king which he contrasted with what he found in the Hausa states, Nupe, Borgu and other Muslim areas, reporting that the wives were never known to abuse that liberty.

After some other encounters, Lander left Zangon Katab to proceed in his journey and was intercepted by four horsemen from the Emir of Zaria who took him back to Zaria, forbidding him to travel to Funda which was at war with the Sokoto caliphate at the moment. He finally returned to England via Badagry.[7]

Later Jihad days and slave trade

The itinerate traders of Zangon Kataf in the 1830s began regarding themselves as subjects of the Emir of Zaria, again refusing to pay tribute to the Atyap instead, began showing signs of independence from the Atyap which by the 1840s reached its climax. It was then that the Atyap were conferred the dhimmi status as a non-Muslim group in which they were expected to pay the protection fee (jizya) to the Emir of Zaria to avoid jihadist attack, which also included an annual donation of 15 slaves, 20 raffia mats, some kegs of honey and bundles of raffia fronds to be collected from each clan by their princes (or Hausa: magajis). The jekada appointed by Zaria, then collect these items and transport them to the Emir on Zaria. The Atyap however, did not feel obliged to pay for these tributes because they felt it was only applicable to non-Muslims living in a Muslim state and being that they were in their own state, refused paying. Some of the jekadas from Zaria were usually attacked and killed by the Atyap and the Hausa traders and their cattle sometimes face similar treats. The captives realised were sold into slavery to the Irigwe middlemen in particular and others with political status held ransom from Zaria.

The emergence of Mamman Sani as Emir of Zaria (1846 -1860) came with aggression on the Aniragu, Atumi, Koono, Anu, Avono, Agbiri, Avori and Kuzamani in the Kauru area who refused allying with the Emir of Zaria through the Sarkin Kauru, viewing the alliance as a loss of independence.

The Bajju in 1847 were affected by this aggression when Mamman attacked Bi, one of their villages. They responded by attacking the Hausa and Fulani in their territory holding some captives and compelling the emirs of Zaria and Jema'a to pay tribute to them for some years, after which the latter launched a counter offensive against them to set their people free.

The new Emir of Zaria few decades later, Abdullahi in 1871 appointed Tutamare and Yawa, deploying them across the Zangon Katab area. Tutamare was a Bakulu convert to Islam who was given the Kuyambana title and put in-charge of extracting tributes from his people and the Anghan, a task which became difficult to accomplish and his title snatched by the District Head of Zangon Katab. Yawa on the other hand was appointed in the 1880s as Sarkin Yamma (chief of the west) by Emir Sambo (1881 - 1889). His functions include policing the western sections against Ibrahim Nagwamatse of Kontagora's forces and raid for slaves. He used Wogon (Kagarko), Ajure (Kajuru) and Kachia as bases to raid the Adara, Gbagyi, Atyap, Koro, Bakulu and Anghan.

The next Emir of Zaria Yero (1890 - 1897) organized a force of royal slaves and equipped them with firearms to instill terror on the local population, seizing people into slavery, food supplies, preventing them from cultivating their crops and causing widespread starvation and deaths to force them into submission. Instead, they allied with one another against Zaria in the 19th century. The insecurity and economic turbulence brought by the raids and tributes were meant to create avenues for slavery and its trade in the area and succeeded to a great extent.

In a bid to penetrate the area, Zaria collided one clan against another and was able weaken certain sections of the Atyap polity through trickery, forcing them into Amana relationships with her. Some of the towns they penetrated included: Ataghyui, Magang, Makunfwuong, Kanai and Sako. Zaria's expectations were to have them as bases for her advancing and retreating forces, and to feed her with vital information. Through them she penetrated Atyapland and enforced the payment of tributes, which she increased in the early 1890s from 15 to 100 slaves annually. The Atyap however stopped paying these tributes in 1894 and Zaria reacted by sending a large army of fighters to Zangon Kataf from Zaria, assisted by the Sarkin Kauru who knew the area very well. The Atyap, however, through an ambush completely defeated the combined forces and sold some of the fighters captured into slavery then returned to Zangon Katab and burnt down the Zango settlement, again disrupting trade in the area.

The last pre-colonial Emir of Zaria, Kwassau (1898 - 1903) in 1899, launched a carefully planned attack on the Atyap for disrupting the trade in the area and succeeded in reestablishing the Amana Pact relationship with some Atyap lineages and settlements (Ataghyui, Sako, Mazaki and Kanai), using Mazaki as an attack base and also used the Atsam against the Atyap by making them block the Atyap escaping via the Kaduna River. This attack came at the time of the A̠nak Festival when people were less ready for war. Kwassau was said to have destroyed many lives in the Santswan Forest where many Atyap escapees went hiding by clearing the forest and was also said to have vowed not to spare a soul and needed neither slave nor concubine and the Kaduna River was said to flowed with the blood of his victims who were estimated to have numbered about a thousand at that very event.

Kwassau, however, met with a strong resistance at Magata, Mayayit, Makarau and Ashong Ashyui where he resorted to impalling his victims on stakes and burning others alive. In the course of this war, the leading warrior as Achi in Achi et al (2019) puts it, "the most gallant military commander of the Atyap anti-slavery forces, Marok Gandu of Magata, was captured by the Hausa forces who executed him by impalling on a stake, while others like Zinyip Katunku and Kuntai Mado of Mashan were said to have been buried alive, in 1902.

The Kwassau wars caused many southwards migrations of Atyap to neighbouring areas of Asholyio, Agworok, Bajju and Koro, and many never returned since then. This migration phase is known in Tyap as Tyong Kwasa̠u (escape from Kwassau), while those which happened earlier are called Tyong A̠kpat (escape from the Hausa).[7]

Atyap nationalism grew in the 19th century as Fulani jihadists tried to extend their control in this and other parts of central Nigeria. [27]

20th century

Colonial Nigeria

The British military entered Atyapland April 3, 1903 and took it without a fight from the Atyap, probably due to the fatigue incurred on the Kwassau wars which the people were still recovering from. The British then left Atyapland and moved to the Bajju who, however, put up a fight but fell to the British. In 1904, the British moved to the Agworok in what was known as the Tilde Expedition, starting from Jema'a Daroro on November 7, 1904.[7] When the British conquered the north and Middle Belt of Nigeria 1903-4, they followed a system of indirect rule. The British gave the emir of Zaria increased powers over the Atyab through the village heads that he appointed, and causing increasing resentment.[27]

Achi in Achi et al (2019) described the fabrication of the claims by Zaria about her sovereignty over the Atyap a deliberate distortion of history, as many of the polities portrayed by her as dependents we're in reality independent. Accepting these claims, the British in 1912 appealed to the Atyap to acknowledge the emirs of Jema'a and Zaria as their parents chiefs in a bid to impose colonial rule through those newfound allies. Earlier, in 1907 the Atyap were placed under Kauru renamed Katuka District and in 1912, the Zangon Katab District was created.[7]

Christian missionaries found fertile ground with the Atyap, who had rejected the Moslem religion. This served to increase tensions between the Atyap and the Hausa. However, one has to be very careful when referring to religious conflicts in Nigeria, as it is not all Atyap people that are Christians, similarly, not all Hausa people are Muslims. Oftentimes, historians make more emphasis on religious factor other than other basic factors like land for example. The Atyap also resented loss of land, considering that they had originally owned all of the Zangon-Kataf territory and had been illegally dispossessed by Hausa intruders.

Atyap anti-colonial movements

With the introduction of taxation, forced labour and compelling of people to cultivate cash crops, causing hardship on the people, the Atyap in 1910 arose against the British in protest, which was crushed by the British but on the long run, led to the people's greater hatred against the Zangon Katab District Head.

A second uprising occurred in 1922, this time around with a combined Atyap-Bajju alliance against the oppressive taxation policies if the British. The British again used force to quell the revolt but failed to arrest the leaders who escaped the area.

During the period if the Great Depression (1929 - 1933), the British abolished the tax payment when the people could not even afford to feed themselves.

During the World War II era (1939 - 1945), a few Atyap were recruited as contribution for the war in southeast Asia and German Africa. The Atyap also produced food crops for internal needs for the feeding of workers in the mines, aerodrome construction sites in Kaduna, Kano and Maiduguri and export of those crops to the colonial army in British West Africa. The increased diversion of labour from food production to the tin mines, railway and road construction and into the army resulted to increase in use of child labour for agricultural activities. The Atyap were, however, denied jobs in the Native Authority. Most of the employees in the 1950s in the Zaria Native Authority were the emir's relatives. Achi (2019) noted that the Atyap were always told "All of us in Zaria division are brothers, whether we be Muslims, Pagans or Christians" but faced discrimination always when it came to employment and reported that in 1953, the Native Authority had 102 staff, 60 being Hausa/Fulani, 42 indigenes from Atyap, Bajju, Bakulu, Anghan, Atsam and Atyecharak - i.e. 25 village scribes, four court scribes, three local police, nine teachers and one departmental mallam.

In 1942, Bajju militants led by Usman Sakwat waged intense anti-colonial struggles directly against the Zaria Emirate and this brewed to the post World War II Atyap-Bajju movement against the colonialists.

The Atyap were up to the 1950s predominantly animists and adherents of the Abwoi religion. On the other hand, the Hausa were Muslims and non-indigenous to the area. However, the British selected persons from the Zaria ruling circles to rule over the Atyap who although had chiefs, but were made to bow to the Hausa aristocrats and any among the Á̠gwam A̠tyap (Atyap chiefs) who refused to do so was severely dealt with mostly by removal or dismissal from office.

The driving force behind the anti-colonial revolts by the Atyap peasants and their Bajju allies had to do with the high taxes, lack of enough schools, non-employment of Atyap indigenes even in the Native Authority and prevalent societal social injustice and domination by Zaria feudal aristocrats, their arrogance, contempt for the Atyap culture and above all, the demand for the creation of an Atyap Chiefdom, modelled after the those of Moroa, Kagoro and Kwoi which had indigenous chiefs and were not under any emirate.

In May 1946, the Atyap revolted by refusing to pay tax to the Hausa, refused forced labour, boycotted the Zangon Kataf market and the refusal of youths to obey orders of the Hausa District Head, regarded the alkali and "pagan" courts (latter established about 1927) and threatened to attack the about 5,000 Hausa/Fulani inhabitants of Zangon Katab and demanding for the separation of the Atyap area friend Zaria Emirate. The situation became delicate and the Resident, G. D. Pitcairn blamed the Chief of Gworok (Kagoro), Gwamna Awan, appointed as the first Christian chief in the whole of Zaria province in 1945, a year earlier, for fuelling the crisis because the Zaria feudal ruling circles were uncomfortable with his being chief and wanted him out by all means.

Many Atyap were arrested enmasse, including Ndung Amaman of Zonzon who was an elder in support of the resistance, who later died of a heart-related complication in detention in Zaria and 25 others convicted of offence against taxation ordinance and sentenced to three months imprisonment with hard labour. Others like Sheyin (AKA Mashayi) and five others were convicted of unlawfully assaulting the police and resisting authority and sentenced to two to six months imprisonment with hard labour. The British knew what to do but refused to ensure that justice was done instead continued to promote feudal tyranny against the Atyap. Usman Sakwat and 12 other Bajju were also thrown into prison for an entire year.

In January 1954, soldiers were sent to Zangon Katab town by the British to avert an impending attack by Atyap and Bajju extremist groups against the Hausa population.[7]

Post colonial Nigeria

After independence in 1960, General Yakubu Gowon (1966–1975) introduced reforms, letting the Atyap appoint their own village district heads, but the appointees were subject to approval by the emir, and were therefore often seen as puppets.[27]

Much earlier in 1922 the then emir of Zaria acquired a stretch of land in Zango town, the Atyap capital, with no compensation. In 1966 the emir gave the land, now used as a market, to the Hausa community. The Atyap complained that the Hausa traders treated them as slaves in this market.[28]

To reduce the tensions, after the death of the Hausa District Head of Zangon Kataf in 1967, an Atyap Bala Ade Dauke was made the first indigenous District Head of Zangon Kataf and Kuyambanan Zazzau and remained so for the next 28 years.[29]

Tensions steadily increased, flaring up in February 1992 over a proposal to move the market to a new site, away from land that had been transferred to the Hausas. The proposal by the first Atyap head of the Zangon Kataf Local Government Area was favoured by the Atyap who could trade beer and pork on the neutral site and opposed by the Hausa, who feared loss of trading privileges. Over 60 people were killed in the February clashes. Further violence broke out in Zango on May 15/16, with 400 people killed and most buildings destroyed. When the news reached Kaduna, rampaging Hausa youths killed many Christians of all ethnic groups in retaliation.[30]

In the aftermath, many Hausa fled the area, although some returned later, having no other home.[26] A tribunal set up by the Babangida military government sentenced 17 people to death for alleged complicity in the killings, including a former military governor of Rivers State, Major-General Zamani Lekwot, an Atyap. The sentences were eventually reduced to gaol terms.[31] It was said that Lekwot's arrest was due to his feud with Ibrahim Babangida, then Head of State. No Hausa were charged.[32]

An Atyap Chiefdom was created in 1995 following the recommendation of a committee headed by Air Vice Marshall Usman Mu'azu that investigated the cause of the uprising.[25]

For some time, the Atyap had been increasingly speaking Hausa, the primary (i.e. major) language of the region. However, after the violent clashes in 1992 there has been a strong trend back to use of Tyap.[33]

21st century

Continued tension and outbreaks of violence were reported as late as 2006.[26]

The Atyap Chiefdom was upgraded to first class in 2007. In 2010 the president of Atyap Community Development Association (ACDA) said that since the chiefdom was established there had been only a few occasions when it was necessary to intervene to resolve misunderstandings.[25][34]

Notable People

- Maj. Gen. Zamani Lekwot (Rtd.), MNI: Military Governor of Rivers State, Nigeria (1975-1978); Nigerian Ambassador/High Commissioner to the Republics of Senegal, Mauritania, Cape Verde and The Gambia.[35]

- AVM Ishaya Shekari (Rtd.): Former Military Governor of Kano State (1978-1979), Nigeria; also a business mogul.

- Lt. Col. Musa Bityong (late)

- Engr. Andrew Laah Yakubu (Rtd.): Group Managing Director of the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation, NNPC (2012-2014).

- Sen. Isaiah Balat (Late): Former Nigerian Minister of State for Works and Housing (1999-2000); Senator representing Kaduna South Senatorial District (2003-2007); also a businessman and founder of Gora Oil and Gas.

- Sen. Danjuma Laah: Senator representing Kaduna South Senatorial District (2015-Date); also a businessman in the hospitality industry.

- Sunday Marshall Katung (Barr.): Former member of the Nigerian House of Representatives, representinɡ Jaba/Zanɡon-Kataf federal constituency, and runninɡ mate to the People's Democratic Party candidate in the 2019 Governorship elections of Kaduna State, Nigeria.

- Kyuka Lilymjok (Prof.): A Nigerian writer, philosopher and professor of Law.

- Bala Achi (late): A renown Niɡerian historian, educationist and writer and first Head of Station (Chief Research Officer) of the Niɡerian National Commission of Museums and Monuments, Abuja.

See also

References

- Joshua project entry on the Atyap

- "The Atyap Nationality". Atyap Community Online. Archived from the original on 2012-11-17. Retrieved 2010-03-06.

- John Edward Philips (2005). Writing African history. Boydell & Brewer. p. 15ff. ISBN 1-58046-164-6.

- Bala Achi (2005). "Local History in Post-Independent Africa in Writing African history". p. 375.

- Bitiyong, Y. I. (1988). "Preliminary Survey on Some Sites in Zangon Kataf District of Upper Kaduna River Basin": African Study Monograms. pp. 97–107.

- Jemkur, J. F.; Bitiyonɡ, Y. I.; Mahdi, H.; Jada, Y. H. Y. (1989). Interim Report on Fieldwork Conducted on the Nerzit Reɡion (Kaduna State) on Traditional Farminɡ in Niɡeria, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria.

- Achi, B.; Bitiyonɡ, Y. A.; Bunɡwon, A. D.; Baba, M. Y.; Jim, L. K. N.; Kazah-Toure, M.; Philips, J. E. (2019). A Short History of the Atyap. Tamaza Publishinɡ Co. Ltd., Zaria. pp. 9–245. ISBN 978-978-54678-5-7.

- Fagg, B. (1959). The Nok Culture in Prehistory. Journal of Historic Society of Nigeria, 1:4. p. 288-293.

- Greenberg, J.H. (1966). The Languages of Africa 2nd edition. Indiana University, Bloomington. pp. 8–46.

- Meek, C.K. (1928). The Northern Tribes of Nigeria. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co., London. pp. 171–195.

- Temple, C.L. (1985). Notes on the Tribes, Provinces Emirates and States of Northern Provinces of Nigeria. London. pp. 31–222.

- Achi, B. (1987). The Handy System in the Economy of Hausaland. Paper presented at the 32nd Annual Congress of the Historical Society of Nigeria, University of Jos. pp. 1–15.

- James, Ibrahim (2000). The Settler Phenomenon in the Middle Belt and the Problem of National Integration in Nigeria: The Middle Belt (Ethnic Composition of the Nok Culture).

- Akau T. L., Kambai (2014). Tyap-English Dictionary. Benin City: Divine Press. pp. xvi.

- "Tyap". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- Afuwai, Yanet. The Place of Kagoro in the History of Nigeria.

- Yakubu K. Y. (2013). A Reconsideration of the Origin and Migration of Atyap People of Zangon-Kataf Local Government Area of Kaduna State. 2. Journal of Tourism and Heritage Studies. pp. 71–75.

- Achi, Bala. Warfare and Military Architecture Among the Atyap.

- Meek, C.K. (1931). Tribal Studies in Northern Nigeria. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co., Broadway House, London. pp. 58–76.

- Ninyio, Y. S. (2008). Pre-colonial History of Atyab (Kataf). Ya-Byangs Publishers, Jos. p. 93. ISBN 978-978-54678-5-7.

- Gunn, H. D. (1956). Pagan People of the Central Area of Nigeria. London. p. 21.

- "The Culture and Religion". Atyap Community Online. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2010-03-06.

- Ayuba Kefas (2016). Atyap People, Culture and Language. Unpublished. p. 12.

- "Ministry of Local Government Affairs". Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- IBRAHEEM MUSA (7 March 2010). "Peace has returned to Zangon Kataf -Community leader". Sunday Trust. Archived from the original on 2010-03-13. Retrieved 2010-03-07.

- "They Do Not Own This Place" (PDF). Human Rights Watch. April 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 March 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-06.

- Tom Young (2003). Readings in African politics. Indiana University Press. p. 75.76. ISBN 0-253-21646-X.

- Toyin Falola (2001). Violence in Nigeria: The Crisis of Religious Politics and Secular Ideologies. University Rochester Press. p. 216. ISBN 1-58046-052-6.

- Yahaya, Aliyu (Spring 2016). "Colonialism in the Stateless Societies of Africa: A Historical Overview of Administrative Policies and Enduring Consequences in Southern Zaria Districts, Nigeria". 8 (1). Retrieved August 10, 2020. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Ernest E. Uwazie; Isaac Olawale Albert; G. N. Uzoigwe (1999). Inter-ethnic and religious conflict resolution in Nigeria. Lexington Books. p. 106. ISBN 0-7391-0033-5.

- Agaju Madugba (2001-09-09). "Zangon-Kataf: For Peace to Endure". ThisDay. Archived from the original on 2005-11-26. Retrieved 2010-03-06.

- Yusuf Yariyok (February 4, 2003). "FIGHTING MUHAMMAD'S WAR: REVISITING SANI YERIMA'S FATWA". NigeriaWorld. Retrieved 2010-03-06.

- Roger Blench (July 29, 1997). "The Status of the Languages of Central Nigeria" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-26. Retrieved 2010-03-06.

- Ephraim Shehu. "Yakowa at 60: Any legacy?". People's Daily. Retrieved 2010-03-08.

- "PROFILE: Zamani Lekwot". Premium Times Nigeria. Archived from the original on 2014-03-14. Retrieved 2020-05-13.