1987 Tour de France

The 1987 Tour de France was the 74th edition of the Tour de France, taking place from 1 to 26 July. It consisted of 25 stages over 4,231 km (2,629 mi). It was the closest three-way finish in the Tour until the 2007 Tour de France, among the closest overall races in Tour history and the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th place riders each wore the Yellow jersey at some point during the race. It was won by Stephen Roche, the first and so far only Irishman to do so.

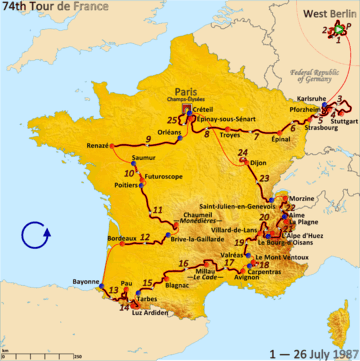

Route of the 1987 Tour de France | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Race details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dates | 1–26 July | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stages | 25 + Prologue | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Distance | 4,231 km (2,629 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Winning time | 115h 27' 42" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Results | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The winner of the 1986 Tour de France, Greg LeMond was unable to defend his title following a shooting accident in April.

Following Stage 1, Poland's Lech Piasecki became the first rider from the Eastern Bloc to lead the Tour de France.[1][2] He was one of eight different men to wear yellow, a new record for the Tour.[2]

Teams

The number of cyclists in one team was reduced from 10 to 9, to allow more teams in the race.[1] The 1987 Tour started with 207 cyclists, divided into 23 teams.[3] Of these, 62 were riding the Tour de France for the first time.[4] The average age of riders in the race was 27.05 years,[5] ranging from the 20-year-old Jean-Claude Colotti (RMO–Cycles Méral–Mavic) to the 36-year-old Gerrie Knetemann (PDM–Concorde).[6] The Caja Rural–Orbea cyclists had the youngest average age while the riders on Del Tongo had the oldest.[7]

The teams entering the race were:[3]

- 7-Eleven

- ANC–Halfords

- BH

- Café de Colombia–Varta

- Caja Rural–Orbea

- Carrera Jeans–Vagabond

- Del Tongo

- Fagor–MBK

- Hitachi–Marc

- Joker–Merckx

- Kas

- Panasonic–Isostar

- PDM–Concorde

- Postobón–Manzana–Ryalcao

- Reynolds

- Roland–Skala

- RMO–Cycles Méral–Mavic

- Superconfex–Kwantum–Yoko–Colnago

- Supermercati Brianzoli–Chateau d'Ax

- Système U

- Teka

- Toshiba–Look

- Vétements Z–Peugeot

Pre-race favourites

Shortly before the Tour, on 20 April 1987, the defending champion Greg LeMond was accidentally shot by his brother-in-law while hunting turkeys. He was unable to start the 1987 Tour, and because Bernard Hinault (second placed in 1986, and the only rider to seriously challenge LeMond in 1986) had retired, the Tour started without a clear favourite.

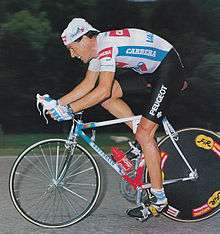

Only one previous winner started in the 1987 Tour: Laurent Fignon, winner in 1983 and 1984. Since then, Fignon had struggled with his form, but in the first months of 1987, Fignon had finally shown some good results. LeMond's place as leader of the Toshiba team was now taken by Jean-François Bernard. He had finished in twelfth place in the previous year as helper of LeMond and Hinault, so more was expected from him now. The Carrera team was led by Stephen Roche. For Roche, the months before the 1987 Tour had gone well, having won the 1987 Giro d'Italia. In the recent Tours, Pedro Delgado had shown improving results, and he had some talented helpers in his PDM team, so he was also considered a contender.[8]

Route and stages

In 1985, it was announced that the 1987 Tour would start in West-Berlin, to celebrate that it was 750 years ago that the city was founded.[9] The 1987 Tour de France started on 1 July, and had one rest day, in Avignon.[10] There were 25 stages (and a prologue), more than ever before.[8] The highest point of elevation in the race was 2,642 m (8,668 ft) at the summit of the Col du Galibier mountain pass on stage 21.[11][12]

| Stage | Date | Course | Distance | Type | Winner | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | 1 July | West Berlin (West Germany) | 6 km (3.7 mi) | Individual time trial | ||

| 1 | 2 July | West Berlin (West Germany) | 105 km (65 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 2 | 2 July | West Berlin (West Germany) | 41 km (25 mi) | Team time trial | Carrera Jeans–Vagabond | |

| 3 | 4 July | Karlsruhe (West Germany) to Stuttgart (West Germany) | 219 km (136 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 4 | 5 July | Stuttgart (West Germany) to Pforzheim (West Germany) | 79 km (49 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 5 | 5 July | Pforzheim (West Germany) to Strasbourg | 112 km (70 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 6 | 6 July | Strasbourg to Épinal | 169 km (105 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 7 | 7 July | Épinal to Troyes | 211 km (131 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 8 | 8 July | Troyes to Épinay-sous-Sénart | 206 km (128 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 9 | 9 July | Orléans to Renazé | 260 km (160 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 10 | 10 July | Saumur to Futuroscope | 87 km (54 mi) | Individual time trial | ||

| 11 | 11 July | Poitiers to Chaumeil | 206 km (128 mi) | Hilly stage | ||

| 12 | 12 July | Brive to Bordeaux | 228 km (142 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 13 | 13 July | Bayonne to Pau | 219 km (136 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 14 | 14 July | Pau to Luz Ardiden | 166 km (103 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 15 | 15 July | Tarbes to Blagnac | 164 km (102 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 16 | 16 July | Blagnac to Millau | 216 km (134 mi) | Hilly stage | ||

| 17 | 17 July | Millau to Avignon | 239 km (149 mi) | Hilly stage | ||

| 18 July | Avignon | Rest day | ||||

| 18 | 19 July | Carpentras to Mont Ventoux | 37 km (23 mi) | Mountain time trial | ||

| 19 | 20 July | Valréas to Villard-de-Lans | 185 km (115 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 20 | 21 July | Villard-de-Lans to Alpe d'Huez | 201 km (125 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 21 | 22 July | Le Bourg-d'Oisans to La Plagne | 185 km (115 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 22 | 23 July | La Plagne to Morzine | 186 km (116 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 23 | 24 July | Saint-Julien-en-Genevois to Dijon | 225 km (140 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 24 | 25 July | Dijon | 38 km (24 mi) | Individual time trial | ||

| 25 | 26 July | Créteil to Paris (Champs-Élysées) | 192 km (119 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| Total | 4,231 km (2,629 mi)[17] | |||||

Race overview

The prologue was won by specialist Jelle Nijdam, and none of the favourites lost much time.[8] The second place in the prologue was for Polish cyclist Lech Piasecki, and when he was part of a break-away in the first stage that won a few seconds, he became the new leader in the general classification, the first time that an Eastern-European cyclist lead the Tour de France.[2][1] Piasecki kept his lead in the team time trial of stage 2, but lost it in the third stage when a break-away gained several minutes. Erich Maechler became the new leader. Maechler kept the lead for several stages. After stage nine, Maechler was still leading. The mass-start stages were dominated by break-aways of cyclists who were not considered relevant for the final victory; sixth-placed Charly Mottet was the only cyclist in the top 15 who had real chances of finishing high.[8]

The tenth stage was an individual time trial, and the first real test for the favourites. It was won by Stephen Roche, with Mottet in second place; Mottet became the new leader of the general classification.[8] After a successful escape in the eleventh stage, Martial Gayant became the new leader. The twelfth stage ended in a bunch sprint that did not change the general classification. The Tour arrived in the Pyrenees in the thirteenth stage. Non-climbers, such as Gayant lost more than fifteen minutes, and so the non-climbers were removed from the top positions of the general classification; the new top three was Mottet – Bernard – Roche, all serious contenders for the final victory.[8]

The eighteenth stage was an individual time trial, with a finish on the Mont Ventoux. It was won with a great margin by Jean-François Bernard, who became the new leader of the general classification, and the new hope of the French cycling fans. Bernard was a good climber and a good time-trialist, and had the support of a good team, so he could be able to stay leader until the end of the race.[8] But already in the next stage, Bernard lost considerable time. He had a flat tire just before the top of a climb, and lost contact with the other riders while he had to wait for repairs, and had to spend energy to get back. His rivals Mottet and Roche had made a plan to attack in the feed zone, where cyclists could get their lunch. Mottet and Roche had packed extra food at the start of the stage, and attacked while Bernard was at the back of the peloton. Bernard chased them, but was not able to get back to them, and lost four minutes in that stage, which made Roche the new leader, closely followed by Mottet and Delgado.[8]

In the twentieth stage, the riders went through the Alps, to finish on the Alpe d'Huez. Roche finished in fifteenth place, and lost the lead to Delgado.[8] The pivotal stage was stage 21. In the first part of this stage, the Colombian cyclists of the "Cafe de Colombia" team (including Luis Herrera and Fabio Parra, fifth and sixth in the general classification) kept a high pace, and many cyclists were dropped. Roche, Delgado and Mottet decided to work together to get rid of the Colombian cyclists on the descent of the Galibier, out of fear that Herrera and Parra would leave them behind in the next climbs. Their plan worked, but Delgado's teammates were also dropped. Roche saw this opportunity and escaped, climbing the Madeleine in a small breakaway group.[18] Somewhat later, Delgado's teammates got back to Delgado, and together they chased Roche, and caught him just before the climb of La Plagne. Roche then anticipated that Delgado would keep attacking on the climb. Knowing Delgado was the better climber, Roche decided he would not follow Delgado's attack. Instead, he let Delgado get away until the margin was one minute, giving Delgado the impression that he could safely save energy for the next stages, and at the last part of the stage gave it everything he had to reduce the margin. Roche followed that tactic, and confused not only Delgado, but also the commentators and the Tour organisation. Roche finished a few seconds behind Delgado, and after the finish he collapsed and was given an oxygen mask in an ambulance.[18]

Roche was only 39 seconds behind Delgado in the general classification. Roche could still win the Tour, but it depended on if he could recover in time for the 22nd stage. That stage included the last serious climb of the Tour, so Delgado had his final opportunity to gain time on Roche, and he attacked. However, Roche was able to come back to Delgado twice. Then, Roche attacked, and Delgado could not keep up. Roche won back 18 seconds on Delgado, so he had reduced his margin to 21 seconds.[1] Being a talented time-trialist, he knew that he could easily make up for it on the penultimate stage (an individual time trial at Dijon). Indeed, Roche won almost a minute on Delgado, and this was enough to secure the overall win. This time trial was won by Jean-François Bernard finished the Tour in third place after losing four minutes after the flat tire in the nineteenth stage.[8]

Doping

Bontempi was originally declared winner of the 7th stage, but a few days later, his doping test came back positive for testosterone. Bontempi was set back to the last place of the stage, was penalised with 10 minutes in the general classification, and received a provisional suspension of one month.[19]

One day later, it became public that Dietrich Thurau had tested positive after the eighth stage. At that point, Thurau had already left the race. He was set back to the last place of that stage, and also received a provisional suspension of one month.[20]

The third rider to test positive was Silvano Contini, after the thirteenth stage. He received the same penalty.[21]

Classification leadership and minor prizes

There were several classifications in the 1987 Tour de France, six of them awarding jerseys to their leaders.[22] The most important was the general classification, calculated by adding each cyclist's finishing times on each stage. The cyclist with the least accumulated time was the race leader, identified by the yellow jersey; the winner of this classification is considered the winner of the Tour.[23]

Additionally, there was a points classification, where cyclists were given points for finishing among the best in a stage finish, or in intermediate sprints. The cyclist with the most points lead the classification, and was identified with a green jersey.[24]

There was also a mountains classification. The organisation had categorised some climbs as either hors catégorie, first, second, third, or fourth-category; points for this classification were won by the first cyclists that reached the top of these climbs first, with more points available for the higher-categorised climbs. The cyclist with the most points lead the classification, and wore a white jersey with red polka dots.[25]

There was also a combination classification. This classification was calculated as a combination of the other classifications, its leader wore the combination jersey.[26]

Another classification was the intermediate sprints classification. This classification had similar rules as the points classification, but only points were awarded on intermediate sprints. Its leader wore a red jersey.[27]

The sixth individual classification was the young rider classification. This was decided the same way as the general classification, but only riders under 26 years were eligible, and the leader wore a white jersey. In 1987 the race organisers changed the rules for the young rider classification; from 1983 to 1986, this classification had been as a "debutant classification", open for cyclist that rode the Tour for the first time. In 1987, the organisers decided that the classification should be open to all cyclists less than 25 years of age at 1 January of the year.[26]

For the team classification, the times of the best three cyclists per team on each stage were added; the leading team was the team with the lowest total time. The riders in the team that led this classification were identified by yellow caps.[27] There was also a team points classification. Cyclists received points according to their finishing position on each stage, with the first rider receiving one point. The first three finishers of each team had their points combined, and the team with the fewest points led the classification. The riders of the team leading this classification wore green caps.[27]

In addition, there was a combativity award, in which a jury composed of journalists gave points after each mass-start stage to the cyclist they considered most combative. The split stages each had a combined winner.[28] At the conclusion of the Tour, Régis Clère won the overall super-combativity award, also decided by journalists.[29] The Souvenir Henri Desgrange was given in honour of Tour founder Henri Desgrange to the first rider to pass the summit of the Col du Galibier on stage 21. This prize was won by Pedro Muñoz Machín Rodríguez.[30][11]

- In stage 19, Stephen Roche wore the combination jersey.

Final standings

| Legend | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Denotes the winner of the general classification | Denotes the winner of the points classification | ||

| Denotes the winner of the mountains classification | Denotes the winner of the young rider classification | ||

| Denotes the winner of the combination classification | Denotes the winner of the intermediate sprints classification | ||

General classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Carrera Jeans–Vagabond | 115h 27' 42" | |

| 2 | PDM–Concorde | + 0' 40" | |

| 3 | Toshiba–Look | + 2' 13" | |

| 4 | Système U | + 6' 40" | |

| 5 | Café de Colombia–Varta | + 9' 32" | |

| 6 | Café de Colombia–Varta | + 16' 53" | |

| 7 | Système U | + 18' 24" | |

| 8 | BH | + 18' 33" | |

| 9 | 7-Eleven | + 21' 49" | |

| 10 | Caja Rural–Orbea | + 26' 13" |

Points classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Superconfex–Kwantum–Yoko–Colnago | 263 | |

| 2 | Carrera Jeans–Vagabond | 247 | |

| 3 | PDM–Concorde | 228 | |

| 4 | Toshiba–Look | 201 | |

| 5 | Joker–Merckx | 195 | |

| 6 | Café de Colombia–Varta | 174 | |

| 7 | Système U | 153 | |

| 8 | BH | 135 | |

| 9 | 7-Eleven | 129 | |

| 10 | Café de Colombia–Varta | 128 |

Mountains classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Café de Colombia–Varta | 452 | |

| 2 | BH | 314 | |

| 3 | 7-Eleven | 277 | |

| 4 | PDM–Concorde | 224 | |

| 5 | Café de Colombia–Varta | 180 | |

| 6 | Carrera Jeans–Vagabond | 173 | |

| 7 | Toshiba–Look | 170 | |

| 8 | Reynolds | 147 | |

| 9 | Système U | 137 | |

| 10 | BH | 132 |

Young rider classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7-Eleven | 115h 49' 31" | |

| 2 | Panasonic–Isostar | + 31' 46" | |

| 3 | Kas | + 59' 08" | |

| 4 | Roland–Skala | + 59' 24" | |

| 5 | Caja Rural–Orbea | + 1h 08' 17" | |

| 6 | Café de Colombia–Varta | + 1h 11' 12" | |

| 7 | Vétements Z–Peugeot | + 1h 11' 48" | |

| 8 | Système U | + 1h 14' 23" | |

| 9 | PDM–Concorde | + 1h 20' 01" | |

| 10 | Café de Colombia | + 1h 22' 22" |

Combination classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Toshiba–Look | 72 | |

| 2 | Système U | 70 | |

| 3 | Carrera Jeans–Vagabond | 69 | |

| 4 | Café de Colombia–Varta | 65 | |

| 5 | BH | 65 |

Intermediate sprints classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vétements Z–Peugeot | 249 | |

| 2 | Superconfex–Kwantum–Yoko–Colnago | 178 | |

| 3 | Teka | 142 | |

| 4 | Fagor–MBK | 100 | |

| 5 | Panasonic–Isostar | 70 | |

| 6 | Toshiba–Look | 55 | |

| 7 | Carrera Jeans–Vagabond | 52 | |

| 8 | Système U | 52 | |

| 9 | Vétements Z–Peugeot | 51 | |

| 10 | Joker–Merckx | 35 |

Team classification

| Rank | Team | Time |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Système U | 346h 44' 02" |

| 2 | Café de Colombia–Varta | + 38' 20" |

| 3 | BH | + 56' 02" |

| 4 | Fagor–MBK | + 1h 07' 54" |

| 5 | Toshiba–Look | + 1h 28' 54" |

| 6 | PDM–Concorde | + 1h 34' 11" |

| 7 | Carrera Jeans–Vagabond | + 1h 41' 42" |

| 8 | Panasonic–Isostar | + 1h 47' 02" |

| 9 | 7-Eleven | + 1h 53' 11" |

| 10 | Caja Rural–Orbea | + 2h 22' 44" |

Team points classification

| Rank | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Système U | 1790 |

| 2 | PDM–Concorde | 1804 |

| 3 | 7-Eleven | 1821 |

| 4 | Panasonic–Isostar | 1863 |

| 5 | BH | 2670 |

| 6 | Carrera Jeans–Vagabond | 2718 |

| 7 | Hitachi–Marc | 2766 |

| 8 | Vétements Z–Peugeot | 2813 |

| 9 | Toshiba–Look | 2828 |

| 10 | Fagor–MBK | 3057 |

Aftermath

After the Giro-Tour double victory, Roche would complete the Triple Crown of Cycling by winning the 1987 road race world championship.[8]

Jeff Pierce winning the final stage on the Champs-Élysées is thought to have impressed the presence of United States cycling in the European circuit.[38] Cycling News's Pat Malach wrote that Pierce's win was his defining win for the remainder of his career.[38]

References

- Boyce, Barry (2006). "1987: Drama on La Plagne". Cycling revealed. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- L'Équipe, Leblanc & Armstrong 2003, p. 290.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1987 – The starters". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Tour de France 1987 – Debutants". ProCyclingStats. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "Tour de France 1987 – Peloton averages". ProCyclingStats. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "Tour de France 1987 – Youngest competitors". ProCyclingStats. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "Tour de France 1987 – Average team age". ProCyclingStats. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- McGann & McGann 2008, pp. 171–178.

- "Tour '87 start in West-Berlijn". Leidse Courant (in Dutch). Regionaal Archief Leiden. 11 October 1985. p. 11. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- Augendre 2016, p. 78.

- Augendre 2016, pp. 177–178.

- "Ronde van Frankrijk 87" [Tour de France 87]. de Volkskrant (in Dutch). 30 June 1987. p. 8 – via Delpher.

- "74ème Tour de France 1987" [74th Tour de France 1987]. Mémoire du cyclisme (in French). Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- Zwegers, Arian. "Tour de France GC top ten". CVCCBike.com. Archived from the original on 10 June 2009. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1987 – The stage winners". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- The seventh stage was initially won by Guido Bontempi, who failed a doping test. Second-placed cyclist in that stage Dominguez was promoted to the first place.

- Augendre 2016, p. 110.

- Bordyche, Tom (26 June 2012). "Stephen Roche remembers one special day in 1987". BBC. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- "1987, Part Three: D'ohpe!". Cyclismas. 6 July 2012. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- "Wir haben doch früher alle gedopt" (in German). Die Welt. 23 May 2007. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- "Ook Contini betrapt op dopinggebruik". Leidsch Dagblad (in Dutch). Regionaal archief Leiden. 27 July 1987. p. 11. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, pp. 452–455.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, pp. 452–453.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, pp. 453–454.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, p. 454.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, pp. 454–455.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, p. 455.

- van den Akker 2018, pp. 211–216.

- Augendre 2016, p. 76.

- "Iedere renner kan tien mille verdienen" [Every rider can earn ten mille]. Het Vrije Volk (in Dutch). 1 July 1987. p. 14 – via Delpher.

- "Tour van dag tot dag" [Tour from day to day]. Het Vrije Volk (in Dutch). 27 July 1987. p. 12 – via Delpher.

- Martin 1987, pp. 130–131.

- van den Akker, Pieter. "Informatie over de Tour de France van 1987" [Information about the Tour de France from 1987]. TourDeFranceStatistieken.nl (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1987 – Stage 25 Créteil > Paris". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Tour in cijfers" [Tour in numbers]. Het Parool (in Dutch). 27 July 1987. p. 17 – via Delpher.

- "Clasificaciones oficiales" (PDF). Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 27 July 1987. p. 38. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2019.

- Martin 1987, p. 133.

- Pat Malach (16 March 2012). "Triumph on the Champs-Elysees: Jeff Pierce recalls his solo '87 win in Paris". Cycling News. Future Publishing Limited. Archived from the original on 31 July 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

Bibliography

- Augendre, Jacques (2016). Guide historique [Historical guide] (PDF). Tour de France (in French). Paris: Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- L'Équipe; Leblanc, Jean-Marie; Armstrong, Lance (2003). The Official Tour de France Centennial 1903–2003. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-84358-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martin, Pierre (1987). Tour 87: The Stories of the 1987 Tour of Italy and Tour de France. With contributions from: Penazzo, Sergio; Baratino, Dante; Schamps, Daniel; Vos, Cor. Keighley, UK: Kennedy Brothers Publishing. OCLC 810684532.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McGann, Bill; McGann, Carol (2008). The Story of the Tour de France: 1965–2007. 2. Indianapolis, IN: Dog Ear Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59858-608-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nauright, John; Parrish, Charles (2012). Sports Around the World: History, Culture, and Practice. 2. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-300-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- van den Akker, Pieter (2018). Tour de France Rules and Statistics: 1903–2018. Self-published. ISBN 978-1-79398-080-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Connor, Jeff (2011). Wide-Eyed and Legless: Inside the Tour de France. Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84596-801-4.

- Connor, Jeff (2012). Field of Fire: The Tour de France of '87 and the Rise and Fall of ANC-Halfords. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78057-278-9.

External links

![]()