1907 Tour de France

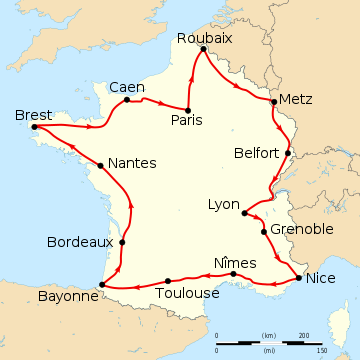

The 1907 Tour de France was the fifth running of the annual Tour de France, one of cycling's Grand Tours. From 8 July to 4 August, the 93 cyclists cycled 4488 km (2,788 mi) in fourteen stages around France. The winner, Lucien Petit-Breton, completed the race at an average speed of 28.47 km/h (17.69 mi/h).[1] For the first time, climbs in the Western Alps were included in the Tour de France. The race was dominated at the start by Émile Georget, who won five of the first eight stages. In the ninth stage, he borrowed a bicycle from a befriended rider after his own broke. This was against the rules; initially he received only a small penalty and his main competitors left the race out of protest. Georget's penalty was then increased and Lucien Petit-Breton became the new leader. Petit-Breton won two of the remaining stages and the overall victory of the Tour.

Route of the 1907 Tour de France followed clockwise, starting in Paris | ||||||||||

| Race details | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dates | 8 July – 4 August | |||||||||

| Stages | 14 | |||||||||

| Distance | 4,488 km (2,789 mi) | |||||||||

| Winning time | 47 points | |||||||||

| Results | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

Innovations and changes

The 1907 Tour de France incorporated 14 stages, which was one more than in 1906. For the first time, roads in Switzerland were included.[1][2] The mountain stages in 1906 had been so successful, according to the organiser Henri Desgrange, that the western Alps were included in the race for the first time.[3]

The 1907 race was also the first time that a car with bicycle repairmen drove behind the riders, to give assistance in solving mechanical problems on bicycles.[2]

As in 1906, the race was decided by a points system. At the end of every stage, the winner was given one point, the next cyclist two points, and so on. After the eighth stage, when there were only 49 cyclists left in the race, the points given in the first eight stages were redistributed among the remaining cyclists, according to their positions in those stages.[2]

Participants

René Pottier, the winner of the 1906 Tour de France, did not defend his title because he had committed suicide in early 1907.[2] Although the riders officially rode the Tour as individuals, some shared the same sponsor and cooperated as if they rode in teams.[4] At the start of the race, it was expected that the riders sponsored by Alcyon and the riders sponsored by Peugeot would compete for the overall victory. Alcyon started with three main contenders: Louis Trousselier, Marcel Cadolle and Léon Georget; Peugeot counted on Emile Georget.[5]

As in the previous years, there were two classes of cyclists, the coureurs de vitesse and the coureurs sur machines poinçonnées. Of the 93 cyclists starting the race, 82 were in the poinçonnée category, which meant that they had to finish the race on the same bicycle as they left, and if it was broken they had to fix it without assistance.[6] The coureurs de vitesse could get help from the car with bicycle repairmen when they had to fix a bicycle, and when a bicycle was beyond repair, they could change it to a new one.[7]

Not all cyclists were competing for the victory; some only joined as tourists. The most notable of them was Henri Pépin. Pépin had hired two riders, Jean Dargassies and Henri Gauban, to ride with him. They treated the race as a pleasure ride, stopping for lunch when they chose and spending the night in the best hotels they could find.[8] Dargassies and Gaubin became the first cyclists in the history of the Tour de France to ride not for their own placings but for another rider's interest. During the race, they found another Tour de France competitor, Jean-Marie Teychenne, lying in a ditch. They helped him get up and fed him; from then on Teychenne also helped Pépin.[3][9]

Race overview

Early in the race, Trousselier, François Faber and Emile Georget were the main contenders.[1] Trousselier, winner of the 1905 Tour de France and eager to win again, won the first stage.[5] In the second stage, the Tour passed the French-German border to finish in Metz, which was then part of Germany. The German authorities allowed the cyclists to finish there, but did not allow the French flag to be flown or the cars of race officials to enter the city.[10] At the end of the stage, Emile Georget seemingly beat Trousselier with a very small margin. After inquiry, Desgrange, the Tour's organiser, decided to put both cyclists in first place,[11] to keep both sponsors satisfied.[5]

In the third stage, the Tour returned to France; at the border, the riders were stopped by two French customs officers and the delay took so long that the stage had to be restarted.[3] During the stage in the Alps, Émile Georget was better than his competitors; he won the stage and became leader of the general classification.[5] Georget won five of the first eight stages, and had a commanding lead.[3] In the seventh stage, Marcel Cadolle, at that time in second place,[12] fell and his handlebar penetrated his knee, after which he had to give up.[5]

During the ninth stage, when Georget was leading the race, he broke the frame of his bicycle[5] at a checkpoint. According to the rules, Georget should have fixed his bicycle alone; he knew this would take him more than five hours, so he switched bicycles with Pierre-Gonzague Privat.[3] This was against the rules, so Georget was given a fine of 500 francs.[1][13] After this stage, won by Petit-Breton, the general classification was as follows:

| Rank | Rider | Points |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Émile Georget | 17 |

| 2 | Lucien Petit-Breton | 37 |

| 3 | Louis Trousselier | 40 |

| 4 | Gustave Garrigou | 53 |

Unsatisfied with the fine given to Georget, Trousselier and the other riders sponsored by Alcyon left the Tour in protest.[5][15]

After the tenth stage, the organisers gave Georget an additional penalty for the bicycle change in the ninth stage. They changed the classification of the ninth stage, moving Georget from 4th on the stage to last (48th place).[13] This effectively cost him 44 points in the general classification and moved him from first to third place.[16] The new classification, after the tenth stage, was

| Rank | Rider | Points |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lucien Petit-Breton | 39 |

| 2 | Gustave Garrigou | 54 |

| 3 | Emile Georget | 64 |

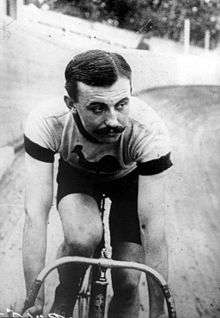

Lucien Petit-Breton became the new leader of the race. Although he had already finished in fifth place and fourth place in previous years,[17] he was still relatively unknown, and had started in the coureurs sur machines poinçonnées category.[1] Petit-Breton finished in the top three in the next stages, so no other cyclist was able to challenge him for the overall victory. At the end of the race, he had increased his lead to a margin of 19 points ahead of Garrigou and 27 points ahead of Georget.[2]

Results

Stage results

In the first and final stages, the cyclists were allowed to have pacers.[18]

| Stage | Date | Course | Distance | Type[lower-alpha 1] | Winner | Race leader | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 July | Paris to Roubaix | 272 km (169 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 2 | 10 July | Roubaix to Metz | 398 km (247 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 3 | 12 July | Metz to Belfort | 259 km (161 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | |||

| 4 | 14 July | Belfort to Lyon | 309 km (192 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | |||

| 5 | 16 July | Lyon to Grenoble | 311 km (193 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | |||

| 6 | 18 July | Grenoble to Nice | 345 km (214 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | |||

| 7 | 20 July | Nice to Nîmes | 345 km (214 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 8 | 22 July | Nîmes to Toulouse | 303 km (188 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 9 | 24 July | Toulouse to Bayonne | 299 km (186 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 10 | 26 July | Bayonne to Bordeaux | 269 km (167 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 11 | 28 July | Bordeaux to Nantes | 391 km (243 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 12 | 30 July | Nantes to Brest | 321 km (199 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 13 | 1 August | Brest to Caen | 415 km (258 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 14 | 4 August | Caen to Paris | 251 km (156 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| Total | 4,488 km (2,789 mi)[20] | ||||||

General classification

Although 110 riders were on the starting list, 17 did not show up, so the race started with 93 cyclists. At the end of the Tour de France, 33 cyclists remained.[2] The cyclists officially were not grouped in teams; some cyclists had the same sponsor, even though they were not allowed to work together.[4]

| Rank | Rider | Sponsor | Points | Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Peugeot-Wolber | 47 | Poinçonnées | |

| 2 | Peugeot-Wolber | 66 | Vitesse | |

| 3 | Peugeot-Wolber | 74 | Vitesse | |

| 4 | Peugeot-Wolber | 85 | Vitesse | |

| 5 | Peugeot-Wolber | 123 | Poinçonnées | |

| 6 | Otav | 150 | Poinçonnées | |

| 7 | Labor-Dunlop | 156 | Poinçonnées | |

| 8 | Labor-Dunlop | 184 | Vitesse | |

| 9 | – | 196 | Poinçonnées | |

| 10 | – | 227 | Poinçonnées |

The total prize money was 25000 French francs, of which 4000 francs were given to Petit-Breton for winning the Tour.[11] In total, he received more than 7000 francs.[22]

Other classifications

Lucien Petit-Breton was also the winner of the "machines poinçonnées" category.[23]

The organising newspaper l'Auto named Emile Georget the meilleur grimpeur. This unofficial title is the precursor to the modern-day mountains classification.[24]

Aftermath

Petit-Breton also started the 1908 Tour de France. He won five stages and the general classification, and became the first cyclist to win the Tour de France two times.[25]

Notes

- In 1907, there was no distinction in the rules between plain stages and mountain stages; the icons shown here indicate which stages included mountains.[2]

References

- "1907 Tour de France". Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 4 May 2009. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- "5ème Tour de France 1907" (in French). Mémoire du cyclisme. Archived from the original on 2 May 2009. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- McGann & McGann 2006, pp. 19–22.

- Thompson 2006, p. 36.

- Amels 1984.

- Wheatcroft 2007.

- Laget et al. 2013.

- Chany & Cazeneuve 1985.

- Dauncey & Hare 2003, p. 73.

- Thompson 2006, p. 68.

- Augendre 2016, p. 9.

- "5ème Tour de France 1907 – 6ème étape" (in French). Mémoire du cyclisme. Archived from the original on 3 May 2009. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- "Le Tour de France". Le Petit Parisien (in French). Gallica Bibliothèque Numérique. 28 July 1907. p. 5. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- "Le Tour de France". Le Petit Parisien (in French). Gallica Bibliothèque Numérique. 26 July 1907. p. 4. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- "Le Tour de France". Le Petit Parisien (in French). Gallica Bibliothèque Numérique. 27 July 1907. p. 4. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- "5ème Tour de France 1907 – 9ème étappe" (in French). Mémoire du cyclisme. Archived from the original on 3 May 2009. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- "Past results for Lucien MAZAN dit PETIT-BRETON (FRA)". Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- "Le Tour de France". Le Petit Parisien (in French). Gallica Bibliothéque Numèrique. 8 July 1907. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1907 – The stage winners". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Augendre 2016, p. 108.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1907 – Stage 14 Caen > Paris". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Le Tour de France" (PDF). Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 8 August 1907. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2019.

- "l'Historique du Tour – Année 1907" (in French). Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 16 July 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- Cleijne 2014, p. 156.

- James, Tom (27 August 2007). "1908: Petit-Breton becomes the first double-winner". Veloarchive. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

Bibliography

- Amels, Wim (1984). De geschiedenis van de Tour de France 1903–1984 (in Dutch). Valkenswaard, Netherlands: Sport-Express. ISBN 978-90-70763-05-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Augendre, Jacques (2016). Guide historique [Historical guide] (PDF). Tour de France (in French). Paris: Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chany, Pierre; Cazeneuve, Thierry (1985). La Fabuleuse Histoire du Tour de France (in French). France: ODIL. ISBN 978-2-8307-0689-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cleijne, Jan (2014). Legends of the Tour. London: Head of Zeus. ISBN 978-1-78185-998-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dauncey, Hugh; Hare, Geoff (2003). The Tour de France, 1903–2003: A Century of Sporting Structures, Meanings and Values. London: Frank Cass & Co. ISBN 978-0-203-50241-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Laget, Françoise; Montgermont, Gilles; Cazaban, Philippe; Laget, Serge (2013). Tour de France: The Official 100th Race Anniversary Edition. London: Hachette UK. ISBN 978-1-78206-415-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McGann, Bill; McGann, Carol (2006). The Story of the Tour de France: 1903–1964. 1. Indianapolis, IN: Dog Ear Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59858-180-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thompson, Christopher S. (2006). The Tour de France: A Cultural History. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24760-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wheatcroft, Geoffrey (2007). Le Tour: A History of the Tour De France. New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-84739-086-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

![]()