1934 Tour de France

The 1934 Tour de France was the 28th edition of the Tour de France, taking place from 3 to 29 July. It consisted of 23 stages over 4,470 km (2,778 mi). The race was won by Antonin Magne, who had previously won the 1931 Tour de France. The French team was dominant, holding the yellow jersey for the entire race and winning most of the stages. Every member of the French team won at least one stage.

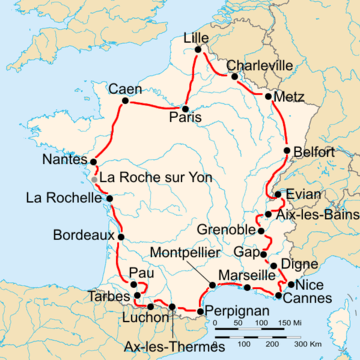

Route of the 1934 Tour de France followed clockwise, starting in Paris | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Race details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dates | 3–29 July | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stages | 23, including one split stage | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Distance | 4,470 km (2,778 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Winning time | 147h 13' 58" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Results | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

French cyclist René Vietto rose to prominence by winning the mountains classification, but even more by giving up his own chances for the Tour victory by giving first his front wheel and later his bicycle to his team captain Magne.

The 1934 Tour de France saw the introduction of the split stage and the individual time trial. Stage 21 was split into two parts, and the second part was an individual time trial, the first one in the history of the Tour de France.

Innovations and changes

The major introduction in 1934 was the introduction of the individual time trial (ITT). There had been time-trial like stages before in the Tour de France, but they had been run as a team time trial. Since the format of the Tour de France changed in 1930 from trade teams to national teams, the Tour organisation had to pay for the housing, travel and feeding for the cyclists. The organisation received the money from the sales of l'Auto, the newspaper that organised the Tour. l'Auto was a morning newspaper, while one of its competitors, Paris-Soir, was an evening paper. Paris-Soir was also following the race, and was able to publish the results the same day, while l'Auto had to wait for the next day, publishing old news. To counter this, the stages in the Tour de France had started later, so they would end after Paris-Soir had to print their newspapers. The Paris-Soir sports editor had countered this by starting his own race, the Grand Prix des Nations, run as an ITT. The first edition in 1932 was not received well by the cyclists, but from 1933 on it was a success. The tour director Henri Desgrange saw the success of the French cyclists in the Grand Prix des Nations, and adapted the individual time trial format in the Tour. Not all cyclists were happy with the ITT. René Vietto, a climber, said it was a dull test of horsepower, while a bike race should also test the head. Other cyclists said the ITT would negate the effect of good teamwork.[1]

The bonification system from the 1933 Tour de France was slightly reduced: now the winner of a stage received 90 seconds bonification, and the second cyclist 45 seconds. In addition to this, the winner of the stage received a bonification equal to the difference between him and the second-placed cyclists, with a maximum of two minutes. This same bonification system was applied on mountain summits that counted for the mountains classification.[2]

In 1933, there had been 40 touriste-routiers, cyclist not competing in a national team, but in 1934 this was reduced to 20.[3] In previous years, these touriste-routiers had to supply their own material and arrange their own hotels; in 1934, the conditions improved and touriste-routiers were given the same treatment as the riders in national teams.[4]

Teams

As was the custom since the 1930 Tour de France, the 1934 Tour de France was contested by national teams. Belgium, Italy, Germany and France each sent teams of 8 cyclists each, while Switzerland and Spain sent a combined team of eight cyclists. In addition, there were 20 individual cyclists; other than in 1933, they were no longer racing under the nomer "touriste-routier" but as "individuel". In total this made 60 cyclists.[5]

Pre-race favourites

The French team of 1934 consisted of all good riders, with the core of the team being the winner of 1933, Georges Speicher, Roger Lapébie, former winner Antonin Magne and Maurice Archambaud, who had performed well in 1933.[1] The French selectors were criticized for selecting René Vietto, a twenty-year-old rider who had only won some small races.[6] The Italian team now included Giuseppe Martano, who had ridden as a touriste-routier in 1933. The Belgian team, which normally included some big contenders, was lackluster.[1]

Route and stages

The highest point of elevation in the race was 2,556 m (8,386 ft) at the summit tunnel of the Col du Galibier mountain pass on stage 7.[7][8]

| Stage | Date | Course | Distance | Type[lower-alpha 1] | Winner | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 July | Paris to Lille | 262 km (163 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 2 | 4 July | Lille to Charleville | 192 km (119 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 3 | 5 July | Charleville to Metz | 161 km (100 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 4 | 6 July | Metz to Belfort | 220 km (140 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 5 | 7 July | Belfort to Evian | 293 km (182 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 8 July | Evian | Rest day | ||||

| 6 | 9 July | Evian to Aix-les-Bains | 207 km (129 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 7 | 10 July | Aix-les-Bains to Grenoble | 229 km (142 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 8 | 11 July | Grenoble to Gap | 102 km (63 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 9 | 12 July | Gap to Digne | 227 km (141 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 10 | 13 July | Digne to Nice | 156 km (97 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 14 July | Nice | Rest day | ||||

| 11 | 15 July | Nice to Cannes | 126 km (78 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 12 | 16 July | Cannes to Marseille | 195 km (121 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 13 | 17 July | Marseille to Montpellier | 172 km (107 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 14 | 18 July | Montpellier to Perpignan | 177 km (110 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 19 July | Perpignan | Rest day | ||||

| 15 | 20 July | Perpignan to Ax-les-Thermes | 158 km (98 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 16 | 21 July | Ax-les-Thermes to Luchon | 165 km (103 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 17 | 22 July | Luchon to Tarbes | 91 km (57 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 18 | 23 July | Tarbes to Pau | 172 km (107 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 24 July | Pau | Rest day | ||||

| 19 | 25 July | Pau to Bordeaux | 215 km (134 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 20 | 26 July | Bordeaux to La Rochelle | 183 km (114 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 21a | 27 July | La Rochelle to La Roche sur Yon | 81 km (50 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 21b | La Roche sur Yon to Nantes | 90 km (56 mi) | Individual time trial | |||

| 22 | 28 July | Nantes to Caen | 275 km (171 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 23 | 29 July | Caen to Paris | 221 km (137 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| Total | 4,470 km (2,778 mi)[12] | |||||

Race overview

The first stage was won by 1933 winner Speicher, and again wore the yellow jersey. In the second stage, he lost his lead as there was a split, with Speicher in the second part and Magne in the leading group, and Magne took over the leading position.[1]

In the fifth stage, Le Grevès and Speicher finished close together. After examining the photo finish, both cyclists shared the time bonus, although Le Grevès was named winner.[1][2]

After stage six, before the heavy climbing in the alps, Magne was leading with almost 8 minutes on second-placed Martano. In the alps, Vietto was the best. He won stages 7 and 9, and climbed to third place in the general classification, half an hour behind Magne. Had he not lost 40 minutes in the first two stages due to flat tires, he would have been the leader of the race. Martano had been able to reduce the margin to Magne to 125 seconds.[1]

The stages 12 to 14, between the Alps and the Pyrenees, were won by French cyclists, without important changes in the general classification. In the fifteenth stage, Magne attacked on an early climb, but Martano did not drop. The big climb of the day was the Puymorens, and Vietto lead while Magne and Martano followed. On the way down, Magne crashed on a pothole,[13] and broke the wooden rim of his front wheel. Martano saw his chances, and raced away. Magne asked Vietto for his bicycle, but Vietto only gave him his front wheel. Magne's frame had been bent in the crash, so when Speicher, the next French cyclist, showed up, Magne took Speicher's bicycle. Vietto had to wait several minutes to get a replacing front wheel, and lost all chances for the stage victory. A photographer was present to take a picture of Vietto, weeping with a bike without a front wheel. When this picture was published, the cycling world was touched, and newspapers proclaimed him "Le Roi René" (King René).[1]

In the sixteenth stage, things got worse for Vietto. He was first over the first two mountains, with his team leader Magne and Martano closely following. On the descent of the Portet d'Aspet, Magne crashed again, and broke his rear wheel. Vietto was unaware of this, and continued. When he was down, a Tour course marshall informed him that his team leader had crashed. Lapébie was far ahead, and all the other French cyclists were far behind, so Magne was without support. Vietto then turned around, and rode back up the mountain. When he reached Magne, Magne took Vietto's bicycle. Magne rode down, reached Lapébie who had waited for him, and together they caught Martano. Vietto had to wait for the service car to bring him a new bicycle, and finally finished four minutes behind Magne, Martano and Lapébie. Vietto was not happy with what had happened, and he said that Magne did not know how to ride, and that Lapébie should not have been so far ahead. Magne on the other hand was grateful for what Vietto and Lapébie did.[1]

In the seventeenth stage, Magne was able to get away from Martano who broke his frame,[14] and finished 13 minutes ahead of thim while winning the stage. Magne now lead with almost 20 minutes.[1] In the eighteenth stage, Magne lost four minutes to Martano. It could have been more, had not Vietto and Lapébie collected the time bonuses on the mountains and the finish.[1]

In the next flat stages, nothing really changed the general classification except the individual time trial in stage 21. Magne won there, increasing the margin to Martano by 8 minutes.[1] Vietto had won back enough time to end in fifth place in the general classification, and won the mountains classification.[13] Magne had ridden consistently in the entire Tour, and had benefitted from his team support. He won his second Tour de France, the fifth in a row for France.[13]

Classification leadership and minor prizes

The time that each cyclist required to finish each stage was recorded, and these times were added together for the general classification. If a cyclist had received a time bonus, it was subtracted from this total; all time penalties were added to this total. The cyclist with the least accumulated time was the race leader, identified by the yellow jersey.

For the mountains classification, 14 mountains were selected by the Tour organisation. On the top of these mountains, ten points were given for the first cyclist to pass, nine points to the second cyclist, and so on, until the tenth cyclist who got one point.

For the fifth time, there was a team competition, this time won by the French team.[2] The team classification was calculated in 1934 by adding up the times of the best three cyclists of a team; the team with the least time was the winner. The fifth national team that started, the Belgian team, finished with only two cyclists, so according to the rules in 1934 they were no longer eligible for the team classification.[15]

Fourth-placed Félicien Vervaecke became the winner of the "individuals" category.[16] This classification was calculated in the same way as the general classification, but only the cyclists riding as individuals were eligible.[17]

| Stage | Winner | General classification |

Mountains classification[lower-alpha 3] | Team classification | Classification for individuals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Georges Speicher | Georges Speicher | no award | France | Sylvère Maes |

| 2 | René Le Grevès | Antonin Magne | Yves Le Goff | ||

| 3 | Roger Lapébie | ||||

| 4 | Roger Lapébie | Félicien Vervaecke | Félicien Vervaecke | ||

| 5 | René Le Grevès Georges Speicher[lower-alpha 2] |

Yves Le Goff | |||

| 6 | Georges Speicher | Ambrogio Morelli | |||

| 7 | René Vietto | Federico Ezquerra | |||

| 8 | Giuseppe Martano | ||||

| 9 | René Vietto | ||||

| 10 | René Le Grevès | ||||

| 11 | René Vietto | Félicien Vervaecke | |||

| 12 | Roger Lapébie | ||||

| 13 | Georges Speicher | ||||

| 14 | Roger Lapébie | ||||

| 15 | Roger Lapébie | ||||

| 16 | Adriano Vignoli | René Vietto | |||

| 17 | Antonin Magne | ||||

| 18 | René Vietto | ||||

| 19 | Ettore Meini | ||||

| 20 | Georges Speicher | ||||

| 21a | René Le Grevès | ||||

| 21b | Antonin Magne | ||||

| 22 | Raymond Louviot | ||||

| 23 | Sylvère Maes | ||||

| Final | Antonin Magne | René Vietto | France | Félicien Vervaecke | |

Final standings

General classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | France | 147h 13' 58" | |

| 2 | Italy | + 27' 31" | |

| 3 | France | + 52' 15" | |

| 4 | Individual | + 57' 40" | |

| 5 | France | + 59' 02" | |

| 6 | Individual | + 1h 12' 02" | |

| 7 | Germany | + 1h 12' 51" | |

| 8 | Individual | + 1h 20' 56" | |

| 9 | Switzerland/Spain | + 1h 29' 02" | |

| 10 | Switzerland/Spain | + 1h 40' 39" |

| Final general classification (11–39)[20] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Rider | Team | Time |

| 11 | France | + 1h 52' 21" | |

| 12 | France | + 2h 03' 21" | |

| 13 | Individual | + 2h 16' 52" | |

| 14 | Italy | + 2h 21' 09" | |

| 15 | Italy | + 2h 21' 58" | |

| 16 | Italy | + 2h 32' 38" | |

| 17 | Switzerland/Spain | + 2h 35' 17" | |

| 18 | Belgium | + 2h 44' 47" | |

| 19 | Switzerland/Spain | + 2h 53' 03" | |

| 20 | Switzerland/Spain | + 2h 55' 26" | |

| 21 | Individual | + 2h 57' 51" | |

| 22 | Germany | + 3h 01' 13" | |

| 23 | Individual | + 3h 01' 48" | |

| 24 | Italy | + 3h 22' 40" | |

| 25 | France | + 3h 26' 26" | |

| 26 | Individual | + 3h 30' 51" | |

| 27 | Individual | + 3h 55' 39" | |

| 28 | Individual | + 3h 57' 54" | |

| 29 | Individual | + 4h 00' 09" | |

| 30 | Switzerland/Spain | + 4h 03' 25" | |

| 31 | Individual | + 4h 27' 07" | |

| 32 | Belgium | + 4h 28' 12" | |

| 33 | Individual | + 4h 29' 40" | |

| 34 | Individual | + 4h 38' 57" | |

| 35 | Individual | + 4h 39' 37" | |

| 36 | Individual | + 5h 00' 50" | |

| 37 | Germany | + 5h 46' 38" | |

| 38 | Germany | + 6h 37' 55" | |

| 39 | Italy | + 7h 15' 36" | |

Mountains classification

| Stage | Rider | Height | Mountain range | Winner |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | Ballon d'Alsace | 1,178 metres (3,865 ft) | Vosges | Félicien Vervaecke |

| 6 | Aravis | 1,498 metres (4,915 ft) | Alps | Félicien Vervaecke |

| 7 | Galibier | 2,556 metres (8,386 ft) | Alps | Federico Ezquerra |

| 8 | Côte de Laffrey | 900 metres (3,000 ft) | Alps | Vicente Trueba |

| 9 | Vars | 2,110 metres (6,920 ft) | Alps | René Vietto |

| 9 | Allos | 2,250 metres (7,380 ft) | Alps | René Vietto |

| 11 | Braus | 1,002 metres (3,287 ft) | Alps-Maritimes | René Vietto |

| 11 | Castillon | 555 metres (1,821 ft) | Alps-Maritimes | René Vietto |

| 16 | Col de Port | 1,249 metres (4,098 ft) | Pyrenees | René Vietto |

| 16 | Portet d'Aspet | 1,069 metres (3,507 ft) | Pyrenees | Adriano Vignoli |

| 17 | Peyresourde | 1,569 metres (5,148 ft) | Pyrenees | René Vietto |

| 17 | Aspin | 1,489 metres (4,885 ft) | Pyrenees | Antonin Magne |

| 18 | Tourmalet | 2,115 metres (6,939 ft) | Pyrenees | René Vietto |

| 18 | Aubisque | 1,709 metres (5,607 ft) | Pyrenees | René Vietto |

| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | France | 111 | |

| 2 | Switzerland/Spain | 93 or 95 | |

| 3 | Italy | 78 | |

| 4 | Individual | 76 | |

| 5 | Switzerland/Spain | 75 | |

| 6 | France | 69 | |

| 7 | Individual | 54 | |

| 8 | Individual | 43 | |

| 9 | Individual | 36 | |

| 10 | Switzerland/Spain | 21 |

Aftermath

The individual time trial that was introduced in 1934 was a success, and has been used since then in almost every year.

René Vietto, who had sacrificed his Tour chances for his team leader Magne, was convinced that he could have won the Tour instead.[1][6]

Notes

- In 1934, there was no distinction in the rules between plain stages and mountain stages; the icons shown here indicate whether the stage included mountains that counted for the mountains classification.

- Le Grevès and Speicher were both declared winner of the fifth stage.

- No jersey was awarded to the leader of the mountains classification until a white jersey with red polka dots was introduced in 1975.[19]

References

- McGann & McGann 2006, pp. 112–119.

- "28ème Tour de France 1934" (in French). Mémoire du cyclisme. Archived from the original on 20 July 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- "Des modifications au réglement" (PDF). l'Ouest-Eclair (in French). 8 September 1933. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- "Nieuwe plannen van Desgrange". Het volk : dagblad voor de arbeiderspartij (in Dutch). Delpher. 6 September 1933. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1934 – The starters". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Tom James (15 August 2003). "1934: Vietto's great sacrifice". VeloArchive. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- Augendre 2016, pp. 177–178.

- Cossins 2013, pp. 50–51.

- Augendre 2016, p. 32.

- Arian Zwegers. "Tour de France GC top ten". CVCC. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2009.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1934 – The stage winners". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Augendre 2016, p. 108.

- Barry Boyce (2004). "1934: "Roi" Rene's Regal Sacrifice". Top 25 All Time Tours. Cycling revealed. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- "1934: Antonin Magne wint dankzij de opoffering van René Vietto" (in Dutch). tourdefrance.nl. 19 March 2003. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- "Ayer terminó la Vuelta a Francia con el previsto y magnífico del francés Antonin Magne" (PDF). Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 30 July 1934. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 July 2012.

- "l'Historique du Tour - Année 1934" (in French). Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 15 May 2010. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- "Il "Tour" si è concluso con una brillante tappa - Classifica degl'isolati". Il Littoriale (in Italian). Biblioteca digitale. 30 July 1934. p. 6. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- van den Akker, Pieter. "Informatie over de Tour de France van 1934" [Information about the Tour de France from 1934]. TourDeFranceStatistieken.nl (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, p. 454.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1934 – Stage 23 Caen > Paris". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Augendre 2016, pp. 175–192.

Bibliography

- Augendre, Jacques (2016). Guide historique [Historical guide] (PDF). Tour de France (in French). Paris: Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cossins, Peter (2013). Le Tour 100: The definitive history of the world's greatest race. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-1-84403-759-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McGann, Bill; McGann, Carol (2006). The Story of the Tour de France: 1903–1964. 1. Indianapolis, IN: Dog Ear Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59858-180-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nauright, John; Parrish, Charles (2012). Sports Around the World: History, Culture, and Practice. 2. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-300-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

![]()