1905 Tour de France

The 1905 Tour de France was the third edition of the Tour de France, held from 9 to 30 July, organised by the newspaper L'Auto. Following the disqualifications after the 1904 Tour de France, there were changes in the rules, the most important one being the general classification not made by time but by points. The race saw the introduction of mountains in the Tour de France, and René Pottier excelled in the first mountain, although he could not finish the race.[1] Due in part to some of the rule changes, the 1905 Tour de France had less cheating and sabotage than in previous years, though they were not completely eliminated. It was won by Louis Trousselier, who also won four of the eleven stages.

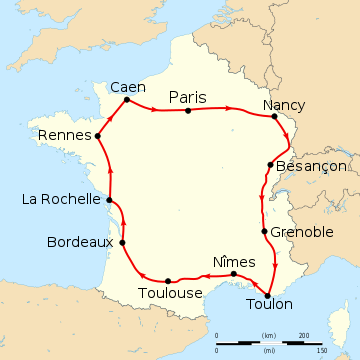

Route of the 1905 Tour de France followed clockwise, starting in Paris | ||||||||||

| Race details | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dates | 9–30 July | |||||||||

| Stages | 11 | |||||||||

| Distance | 2,994 km (1,860 mi) | |||||||||

| Winning time | 35 points | |||||||||

| Results | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

Innovations and changes

After the 1904 Tour de France, some cyclists were disqualified, most notably the top four cyclists of the original overall classification, Maurice Garin, Lucien Pothier, César Garin and Hippolyte Aucouturier. Maurice Garin was originally banned for two years and Pothier for life, so they were ineligible to start the 1905 Tour de France. Of these four, only Aucouturier (who had been "warned" and had a "reprimand inflicted" on him), started the 1905 Tour.[2] They were disqualified by the Union Vélocipédique Française, based on accusations of cheating when there were no race officials around. In 1904 Tour, it was difficult to observe the cyclists continuously, as significant portions of the race were run overnight, and the long stages made it difficult to have officials everywhere.

Because these disqualifications had almost put an end to the Tour de France, the 1905 event had been changed in important ways, to make the race easier to supervise:[3]

- The stages were shortened so that no night riding occurred.

- The number of stages increased to 11 stages, almost double from the previous year.

- The winner was selected on points, not time.[4]

The first cyclist to cross the finish line received 1 point. Other cyclists received one point more than the cyclist who passed the line directly before him, plus an additional point for every five minutes between them, with a maximum of ten points. In this way, a cyclist could not get more than 11 points more than the cyclist that crossed the finish line just before him.[5]

As an example for this point system, the result for the first seven cyclists in the first stage is in this table:

| Rank | Cyclist | Time | Difference with previous finisher | Extra points | Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Louis Trousselier | 11h 25' | — | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | Jean-Baptiste Dortignacq | + 3' | 3' | 1 | 2 |

| 3 | René Pottier | + 4' | 1' | 1 | 3 |

| 4 | Hippolyte Aucouturier | + 26' | 22' | 5 | 8 |

| 5 | Henri Cornet | + 26' | 0' | 1 | 9 |

| 6 | Augustin Ringeval | + 1h 40' | 74' | 11 | 20 |

| 7 | Emile Georget | + 2h 40' | 60' | 11 | 31 |

The other important introduction were the mountains. One of Desgrange's staffers, Alphonse Steinès, took Desgrange for a trip over the Col Bayard at 1,246 metres (4,088 ft) and the Ballon d'Alsace at 1,178 metres (3,865 ft), that had an average gradient of 5.2% with 10% at some places,[3][5] to convince Desgrange to use these climbs in the route. Desgrange accepted it, saying that Steinès would take the blame if the mountains would be too hard to climb.[3]{sfn|Laget|Bouvet|2005|pp=190–191} In the two previous editions, the highest point was the Col de la République at 1,145 metres (3,757 ft). In 1905, Desgrange chose to overlook this, and focused instead on the introduction of the Ballon d'Alsace, because he saw that he had missed the opportunity for publicity previously.[7]

There were two categories of riders, the coureurs de vitesse and the coureurs sur machines poinçonnées.[8] The riders in the first category were allowed to change bicycles, which could be an advantage in the mountains, where they could use a bicycle with lower gears.[3] The riders in the machines poinçonnées category had to use the same bicycle in the entire race, and to verify this, their bicycles were marked.

Participants

Before the race started, 77 riders had signed up for the race.[9] Seventeen of those did not start the race, so the Tour began with 60 riders, including former winner Henri Cornet and future winners René Pottier and Lucien Petit-Breton.[5] The riders were not grouped in teams, but most of them rode with an individual sponsor. Two of the cyclists—Catteau and Lootens—were Belgian, all other cyclists were French. Leading up to the start of the Tour, Wattelier, Trousselier, Pottier and Augereau were all considered the most likely contenders to win the event.[10]

Race overview

Despite the rule changes, there were still protesters among the spectators; in the first stage all riders except Jean-Baptiste Dortignacq punctured due to 125 kg of nails spread along the road.[1][4] The first stage was won by Louis Trousselier. Trousselier was serving the army, and had requested his commander leave for the Tour de France; this was allowed for 24 hours.[11] After he won the first stage and led the classification, his leave was extended until the end of the Tour.[12] From 60 starting cyclists, only 15 cyclists reached the finish line within the time limit;[13] 15 more reached the finish after the limit and the rest took the train.[14] The Tour organiser Desgrange wanted to stop the race, but was persuaded by the cyclists not to do so, and allowed all cyclists to continue with 75 points.[13][14]

In the second stage, the first major climb, the Ballon d'Alsace, made its debut. Four riders were the fastest climbers: Trousselier, René Pottier, Cornet and Aucouturier. Of those four, Trousselier and Aucouturier were the first to be dropped, and Cornet had to drop in the final kilometers.[3] The top was therefore reached first by René Pottier, without dismounting, at an average speed of 20 km/h.[4] Cornet, who reached the top second, had to wait 20 minutes for his bicycle with higher gear, because his support car had broken down.[3] Later Aucouturier caught Pottier, and dropped him, and won the stage.[3] Pottier became second in the stage and led the classification.[1] Seven cyclists did not reach the finish in time, but they were again allowed to start the next stage.[15]

In the third stage, Pottier had to abandon due to tendinitis.[16] The lead was back with Trousselier, who also won the stage.

In the fourth stage, the Côte de Laffrey and the Col Bayard were climbed, the second and third mountains of the Tour de France.[5] Julien Maitron reached both tops first, but Aucouturier won the stage. Trousselier finished in second place, still leading the overall classification, although with the same number of points as Aucouturier.[17]

In the fifth stage, Trousselier won, and because Aucouturier finished in twelfth place, Trousselier had a big lead in the general classification. After the fifth stage, Aucouturier could no longer challenge Trousselier for the lead.[18]

In the seventh stage to Bordeaux, Trousselier punctured after only a few kilometers. The rest of the cyclists quickly sped away from him, and Trousselier had to follow them alone for 200 km. A few kilometers before Bordeaux, Trousselier caught up with the rest, and even managed to win the sprint.[11] Louis Trousselier kept his lead until the end of the race, winning five stages. Trousselier was accused of bad sportsmanship: he reportedly smashed the inkstands of a control post to prevent his opponents from signing.[16] Unlike the 1904 Tour de France, no stage winners, nor anyone from the top ten of the general classification, were disqualified.

Results

Stage results

In the first and last stage, the cyclists were allowed to use pacers. All the 11 stages were won by only three cyclists:[8]

| Stage | Date | Course | Distance | Type[lower-alpha 1] | Winner | Race leader | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9 July | Paris to Nancy | 340 km (210 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 2 | 11 July | Nancy to Besançon | 299 km (186 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | |||

| 3 | 14 July | Besançon to Grenoble | 327 km (203 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 4 | 16 July | Grenoble to Toulon | 348 km (216 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | |||

| 5 | 18 July | Toulon to Nîmes | 192 km (119 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 6 | 20 July | Nîmes to Toulouse | 307 km (191 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 7 | 22 July | Toulouse to Bordeaux | 268 km (167 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 8 | 24 July | Bordeaux to La Rochelle | 257 km (160 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 9 | 26 July | La Rochelle to Rennes | 263 km (163 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 10 | 28 July | Rennes to Caen | 167 km (104 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 11 | 29 July | Caen to Paris | 253 km (157 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| Total | 2,994 km (1,860 mi)[20] | ||||||

General classification

The cyclists officially were not grouped in teams; some cyclists had the same sponsor, even though they were not allowed to work together.[21]

| Rank | Rider | Sponsor | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Peugeot-Wolber | 35 | |

| 2 | Peugeot-Wolber | 61 | |

| 3 | Saving | 64 | |

| 4 | JC Cycles | 123 | |

| 5 | JC Cycles | 155 | |

| 6 | JC Cycles | 202 | |

| 7 | Griffon | 231 | |

| 8 | JC Cycles | 248 | |

| 9 | Peugeot-Wolber/Griffon | 255 | |

| 10 | JC Cycles | 304 |

Other classifications

Pautrat was the winner of the coureurs sur machines poinçonnées category, having used the same bicycle through the whole event.[23]

The organising newspaper L'Auto named René Pottier the meilleur grimpeur. This unofficial title is the precursor to the mountains classification.[24]

Aftermath

The tour organisers liked the effect of the points system, and it remained active until the 1912 Tour de France, after which it was reverted to the time system. In 1953, for the 50-years anniversary of the Tour de France, the points system was reintroduced as the points classification, and the winner was given a green jersey. This points classification has been active ever since.

The introduction of mountains in the Tour de France had also been successful. After the introduction of the Vosges in the 1905 Tour de France, in 1906 the Massif Central were climbed, followed by the Pyrenees in 1910 and the Alps in 1911.

The winner Trousselier received 6950 Francs for his victory. The night after he won, he drank and gambled with friends, and lost all the money.[3] In later years, Trousselier would not win a Tour de France again, but he still won eight more stages and finished on the podium in the next year.[25] The unofficial mountain champion of the 1905 Tour de France, Pottier, would be more successful in the next year, when he won the overall classification and five stages.[26]

For L'Auto, the newspaper that organised the Tour de France, the race was a success; the circulation had increased to 100,000.[27]

Notes

- In 1905, there was no distinction in the rules between plain stages and mountain stages; the icons shown here indicate which stages included mountains.[5]

References

- "The Tour – Year 1905". Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 17 July 2010. Retrieved 29 December 2009.

- James, Tom (14 August 2003). "The Tour is finished ..." VeloArchive. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- McGann & McGann 2006, pp. 14–16.

- "1905: A new formula is devised". VeloArchive. 14 August 2003. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- "3ème Tour de France 1905" (in French). Mémoire du cyclisme. Archived from the original on 20 May 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- "Cyclisme – Le Tour de France". Le Petit Parisien (in French). Gallica Bibliothèque Numérique. 11 July 1905. p. 5. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- Van den Bogaart, Ronnie (10 November 2007). "Col de la République was eerste berg in Tour de France" (in Dutch). Sportgeschiedenis. Archived from the original on 26 February 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- Augendre 2016, p. 7.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1905 – The starters". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Vélocipedie – Le Tour de France de 1905". La Croix (in French). Gallica Bibliothèque Numérique. 9 July 1905. p. 4. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- Amels 1984, pp. 8–9.

- "Memo Louis Trousselier". CyclingWebsite. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- "3ème Tour de France 1905 – 1ère étape" (in French). Mémoire du cyclisme. Archived from the original on 6 May 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- "Louis Trousselier wint Tour de France 1905" (in Dutch). NieuwsDossier. 8 January 2008. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- "3ème Tour de France 1905 – 2ème étape" (in French). Mémoire du cyclisme. Archived from the original on 6 May 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- Mace, Lorraine (2004). "Convicts of the road". Archived from the original on 12 February 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- "3ème Tour de France 1905 – 4ème étape" (in French). Mémoire du cyclisme. Archived from the original on 6 May 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- Boyce, Barry (2004). "The Restructuring". Cycling revealed. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1905 – The stage winners". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Augendre 2016, p. 108.

- Thompson 2006, p. 36.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1905 – Stage 11 Caen > Paris". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "l'Historique du Tour – Année 1905" (in French). Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 15 July 2009. Retrieved 29 December 2009.

- Cleijne 2014, p. 156.

- "Past results for Louis Trousselier (FRA)". ASO. Archived from the original on 24 June 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2009.

- "Past results for Rene Pottier (FRA)". ASO. Archived from the original on 21 July 2009. Retrieved 20 May 2009.

- "Tour de France" (in Dutch). Koninklijke Bibliotheek. 8 August 2008. Archived from the original on 11 July 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

Bibliography

- Amels, Wim (1984). De geschiedenis van de Tour de France 1903–1984 (in Dutch). Valkenswaard, Netherlands: Sport-Express. ISBN 978-90-70763-05-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Augendre, Jacques (2016). Guide historique [Historical guide] (PDF). Tour de France (in French). Paris: Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cleijne, Jan (2014). Legends of the Tour. London: Head of Zeus. ISBN 978-1-78185-998-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Laget, Serge; Bouvet, Philippe (2005). Cols mythiques du Tour de France (in French). Paris: L'Équipe. ISBN 978-2-915535-09-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McGann, Bill; McGann, Carol (2006). The Story of the Tour de France: 1903–1964. 1. Indianapolis, IN: Dog Ear Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59858-180-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thompson, Christopher S. (2006). The Tour de France: A Cultural History. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24760-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

![]()