1963 Tour de France

The 1963 Tour de France was the 50th instance of that Grand Tour. It took place between 23 June and 14 July, with 21 stages covering a distance of 4,138 km (2,571 mi). Stages 2 and 6 were both two part stages, the first half being a regular stage and the second half being a team or individual time trial.

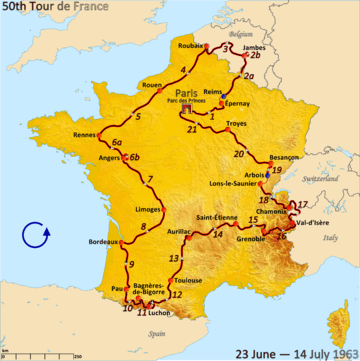

Route of the 1963 Tour de France | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Race details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dates | 23 June – 14 July | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stages | 21, including two split stages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Distance | 4,138 km (2,571 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Winning time | 113h 30' 05" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Results | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Tour organisers were trying to break the dominance of Anquetil, who had won already three Tours, by reducing the time trials length to only 79 km (49 mi), so that the climbing capabilities would be more important.[1]

Nonetheless, the race was won by Anquetil, who was able to stay close to his main rival Federico Bahamontes in the mountains, one time even by faking a mechanical problem in order to get a bicycle that was more suited for the terrain. Bahamontes finished as the second-placed cyclist, but won the mountains classification. The points classification was won by Rik Van Looy.

Teams

The 1963 Tour started with 130 cyclists, divided into 13 teams.[2] The IBAC–Molteni team was a combination of five cyclists from IBAC and five from Molteni, each wearing their own sponsor's jerseys.[1]

The teams entering the race were:[2]

Pre-race favourites

_en_Rik_van_Looy%2C_Bestanddeelnr_915-3093.jpg)

The main favourite before the race was Jacques Anquetil, at that moment already a three-time winner of the Tour, including the previous two editions. Anquetil had shown good form before the Tour, as he won Paris–Nice, the Dauphiné Libéré, the Critérium National and the 1963 Vuelta a España. Anquetil was not sure if he would ride the Tour until a few days before the start; he had been infected by a tapeworm, and was advised not to start.[3] Anquetil had chosen to ride races with tough climbs, to prepare for the 1963 Tour de France.[4]

The major competitor was thought to be Raymond Poulidor, who had shown his capabilities in the 1962 Tour de France.[3]

Route and stages

The 1963 Tour de France started on 23 June in Paris, and had one rest day, in Aurillac.[5] The highest point of elevation in the race was 2,770 m (9,090 ft) at the summit of the Col de l'Iseran mountain pass on stage 16.[6][7]

| Stage | Date | Course | Distance | Type | Winner | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 23 June | Paris to Épernay | 152 km (94 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 2a | 24 June | Reims to Jambes (Belgium) | 186 km (116 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 2b | Jambes (Belgium) | 22 km (14 mi) | Team time trial | Pelforth–Sauvage–Lejeune | ||

| 3 | 25 June | Jambes (Belgium) to Roubaix | 223 km (139 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 4 | 26 June | Roubaix to Rouen | 236 km (147 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 5 | 27 June | Rouen to Rennes | 285 km (177 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 6a | 28 June | Rennes to Angers | 118 km (73 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 6b | Angers | 25 km (16 mi) | Individual time trial | |||

| 7 | 29 June | Angers to Limoges | 236 km (147 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 8 | 30 June | Limoges to Bordeaux | 232 km (144 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 9 | 1 July | Bordeaux to Pau | 202 km (126 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 10 | 2 July | Pau to Bagnères-de-Bigorre | 148 km (92 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 11 | 3 July | Bagnères-de-Bigorre to Luchon | 131 km (81 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 12 | 4 July | Luchon to Toulouse | 173 km (107 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 13 | 5 July | Toulouse to Aurillac | 234 km (145 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 6 July | Aurillac | Rest day | ||||

| 14 | 7 July | Aurillac to Saint-Étienne | 237 km (147 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 15 | 8 July | Saint-Étienne to Grenoble | 174 km (108 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 16 | 9 July | Grenoble to Val d'Isère | 202 km (126 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 17 | 10 July | Val d'Isère to Chamonix | 228 km (142 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 18 | 11 July | Chamonix to Lons-le-Saunier | 225 km (140 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 19 | 12 July | Arbois to Besançon | 54 km (34 mi) | Individual time trial | ||

| 20 | 13 July | Besançon to Troyes | 234 km (145 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 21 | 14 July | Troyes to Paris | 185 km (115 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| Total | 4,138 km (2,571 mi)[10] | |||||

Race overview

In the first stage, four men escaped. One of them was Federico Bahamontes, the winner of the 1959 Tour de France. Bahamontes was known as a climber, so it was unexpected that he gained time on a flat stage.[3] The third stage saw another successful breakaway. Seamus Elliott won the stage, and became the new leader in the race; it was the first time that an Irish cyclist lead the Tour de France.

The time trial in stage 6b was won by Anquetil, with Poulidor in second place. Gilbert Desmet became the new leader. The situation did not change much in the next stages until the stages in the Pyrenees, starting with the tenth stage. Bahamontes lead the first group, but Anquetil was able to stay in that first group, which was a surprise. Anquetil stayed in that first group until the finish, where he outsprinted the rest to win his first mountain stage.[3] In the other two stages in the Pyrenees, Anquetil was able to stay in the first group, lost little time on his competitors, and kept getting closer to Desmet, who was still leading the general classification.

The fifteenth stage was the first in the Alps. Bahamontes won this stage, and in the general classification jumped to second place, three seconds ahead of Anquetil. In the sixteenth stage, Fernando Manzaneque won, eight minutes ahead of Bahamontes and Anquetil who stayed together. Because Desmet was further behind, Bahamontes became the new leader of the race, with a margin of three seconds on Anquetil.

The race was decided in the seventeenth stage. The rules in 1963 did not allow cyclists to change bicycles, unless there was a mechanical problem. Anquetil's team director, Raphaël Géminiani, thought that Anquetil could use a different bicycle on the ascent of the Col de la Forclaz, so he advised Anquetil to fake a mechanical problem on the start of that climb; Géminiani cut through a gear cable, and claimed that it snapped.[11] Anquetil could thus use a light bicycle with lower gears, especially suited for a climb, which gave him an advantage on his competitors. Bahamontes reached the top of the Forclaz first, and only Anquetil had been able to follow him.[12] After the top, Anquetil got his regular bicycle back, and rode to the finish together with Bahamontes. Anquetil won the sprint, and the bonus time made him the new leader.[3][13] As expected, Anquetil won some more time in the time trial in stage 19, and became the winner of the 1963 Tour.

Classification leadership and minor prizes

.jpg)

There were several classifications in the 1963 Tour de France, two of them awarding jerseys to their leaders.[14] The most important was the general classification, calculated by adding each cyclist's finishing times on each stage. The cyclist with the least accumulated time was the race leader, identified by the yellow jersey; the winner of this classification is considered the winner of the Tour.[15]

Additionally, there was a points classification. In the points classification, cyclists got points for finishing among the best in a stage finish, or in intermediate sprints. The cyclist with the most points lead the classification, and was identified with a green jersey.[16]

There was also a mountains classification. The organisation had categorised some climbs as either first, second, third, or fourth-category; points for this classification were won by the first cyclists that reached the top of these climbs first, with more points available for the higher-categorised climbs. The cyclist with the most points lead the classification, but was not identified with a jersey.[17]

For the team classification, the times of the best three cyclists per team on each stage were added; the leading team was the team with the lowest total time. The riders in the team that led this classification wore yellow caps.[18] Carpano and the combined team IBAC-Molteni did not finish with three or more cyclists, so they were not included in the team classification.

In addition, there was a combativity award, in which a jury composed of journalists gave points after each stage to the cyclist they considered most combative. The split stages each had a combined winner.[19] At the conclusion of the Tour, Rik Van Looy won the overall super-combativity award, also decided by journalists.[5]

Final standings

General classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Saint-Raphaël–Gitane–R. Geminiani | 113h 30' 05" | |

| 2 | Margnat–Paloma–Dunlop | + 3' 35" | |

| 3 | Ferrys | + 10' 14" | |

| 4 | Saint-Raphaël–Gitane–R. Geminiani | + 11' 55" | |

| 5 | Flandria–Faema | + 15' 00" | |

| 6 | Flandria–Faema | + 15' 04" | |

| 7 | IBAC–Molteni | + 15' 27" | |

| 8 | Mercier–BP–Hutchinson | + 16' 46" | |

| 9 | Wiel's–Groene Leeuw | + 18' 53" | |

| 10 | G.B.C.–Libertas | + 19' 24" |

Points classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | G.B.C.–Libertas | 275 | |

| 2 | Saint-Raphaël–Gitane–R. Geminiani | 138 | |

| 3 | Margnat–Paloma–Dunlop | 112 | |

| 4 | Wiel's–Groene Leeuw | 111 | |

| 5 | Ferrys | 81 | |

| 6 | Mercier–BP–Hutchinson | 78 | |

| 7 | Mercier–BP–Hutchinson | 77 | |

| 8 | Saint-Raphaël–Gitane–R. Geminiani | 65 | |

| 9 | Margnat–Paloma–Dunlop | 64 | |

| 10 | Flandria–Faema | 54 |

Mountains classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Margnat–Paloma–Dunlop | 147 | |

| 2 | Mercier–BP–Hutchinson | 70 | |

| 3 | Saint-Raphaël–Gitane–R. Geminiani | 68 | |

| 4 | Margnat–Paloma–Dunlop | 51 | |

| 5 | Saint-Raphaël–Gitane–R. Geminiani | 47 | |

| 6 | Wiel's–Groene Leeuw | 46 | |

| 7 | Pelforth–Sauvage–Lejeune | 38 | |

| 8 | IBAC–Molteni | 33 | |

| 9 | Flandria–Faema | 29 | |

| 10 | Flandria–Faema | 27 |

Team classification

| Rank | Team | Time |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Saint-Raphaël–Gitane–R. Geminiani | 340h 35' 25" |

| 2 | Pelforth–Sauvage–Lejeune | + 36' 49" |

| 3 | Flandria–Faema | + 43' 13" |

| 4 | Wiel's–Groene Leeuw | + 59' 03" |

| 4 | Ferrys | + 59' 03" |

| 6 | Margnat–Paloma–Dunlop | + 1h 04' 21" |

| 7 | Mercier–BP–Hutchinson | + 1h 24' 34" |

| 8 | Peugeot–BP–Englebert | + 1h 42' 13" |

| 9 | Kas–Kaskol | + 1h 56' 08" |

| 10 | G.B.C.–Libertas | + 2h 05' 26" |

| 11 | Solo–Terrot | + 4h 18' 36" |

Aftermath

Anquetil, who had been criticized that he just a time trial specialist, showed that he was also capable of mountain stages, and everybody agreed that Anquetil was the best cyclist overall.[13] Anquetil was the first cyclist to win a fourth Tour de France. In the next year, he set the record sharper by winning his fifth Tour. The French public had expected much from Raymond Poulidor, but Poulidor only made the eighth place. Normally, Poulidor was more popular than Anquetil even when Anquetil won, but this time Poulidor received "contemptuous whistles" at the finish in the Parc des Princes,[3] while Anquetil received a standing ovation.[4]

After Anquetil and Géminiani had shown that the rule that bicycle changes were not allowed was easily circumvented by faking a mechanical problem, this rule was removed for the next year.[4]

Notes

- No jersey was awarded to the leader of the mountains classification until a white jersey with red polka dots was introduced in 1975.[17]

References

- "50ème Tour de France 1963" [50th Tour de France 1963]. Mémoire du cyclisme (in French). Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1963 – The starters". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- McGann & McGann 2006, pp. 260–267.

- Boyce, Barry (2004). "Anquetil's 4th victory makes TdF history". CyclingRevealed.

- Augendre 2016, p. 54.

- Augendre 2016, p. 178.

- "Gouden Tour door vier landen" [Golden Tour through four countries]. de Volkskrant (in Dutch). 21 June 1963. p. 13 – via Delpher.

- Zwegers, Arian. "Tour de France GC top ten". CVCC. Archived from the original on 10 June 2009. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1963 – The stage winners". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Augendre 2016, p. 109.

- "Grand Tour Doubles - Jacques Anquetil". Cycle Sport. IPC Media.

- Crepel, Michel (3 November 2010). "Tour de France 1963: Jacques Anquetil au sommet de son art" (in French). Vélo 101.

- Amaury Sport Organisation. "The Tour - Year 1963". letour.fr. Archived from the original on 17 July 2010. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, pp. 452–455.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, pp. 452–453.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, pp. 453–454.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, p. 454.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, p. 455.

- van den Akker 2018, pp. 211–216.

- "Rik Van Looy: twintig ritten in de groene leiderstrui" [Rik Van Looy: twenty rides in the green leader's jersey]. Gazet van Antwerpen (in Dutch). 15 July 1963. p. 11. Archived from the original on 14 February 2019.

- van den Akker, Pieter. "Informatie over de Tour de France van 1963" [Information about the Tour de France from 1963]. TourDeFranceStatistieken.nl (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1963 – Stage 21 Troyes > Paris". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Final classifications". Gazet van Antwerpen (in Dutch). 15 July 1963. p. 12. Archived from the original on 14 February 2019.

- "Clasificacions" [Classifications] (PDF). Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 15 July 1963. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 February 2019.

Bibliography

- Augendre, Jacques (2016). Guide historique [Historical guide] (PDF). Tour de France (in French). Paris: Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McGann, Bill; McGann, Carol (2006). The Story of the Tour de France: 1903–1964. 1. Indianapolis, IN: Dog Ear Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59858-180-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nauright, John; Parrish, Charles (2012). Sports Around the World: History, Culture, and Practice. 2. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-300-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- van den Akker, Pieter (2018). Tour de France Rules and Statistics: 1903–2018. Self-published. ISBN 978-1-79398-080-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

![]()

.jpg)