1985 Tour de France

The 1985 Tour de France was the 72nd edition of the Tour de France, one of cycling's Grand Tours.[1] It took place between 28 June and 21 July 1985. The course ran over 4,109 km (2,553 mi) and consisted of 22 stages and a prologue. The race was won by Bernard Hinault (La Vie Claire), who equalled the record by Jacques Anquetil and Eddy Merckx of five overall victories. Second was Hinault's teammate Greg LeMond, ahead of Stephen Roche (La Redoute).

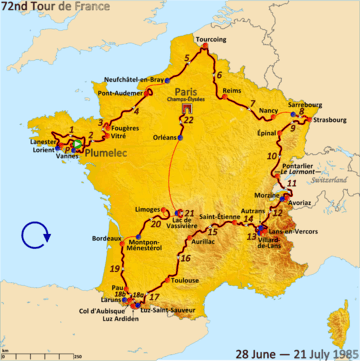

Route of the 1985 Tour de France | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Race details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dates | 28 June – 21 July | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stages | 22 + Prologue, including one split stage | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Distance | 4,109 km (2,553 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Winning time | 113h 24' 23" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Results | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hinault won the race leader's yellow jersey on the first day, in the opening prologue time trial, but time bonuses saw the lead switch to Eric Vanderaerden after stage 1. Hinault's teammate Kim Andersen then took over the yellow jersey following a successful breakaway on stage 4. Hinault regained the race lead after winning the time trial on stage 8. However, a crash on stage 14 into Saint-Étienne broke Hinault's nose, with congestion leading to a bronchitis, which severely hampered his performances. However, he has able to fight off challenges by teammate LeMond and Roche to win the race overall. For his assistance, Hinault publicly pledged to support LeMond for overall victory the following year.

In the Tour's other classifications, Sean Kelly (Skil–Sem–Kas–Miko) won a record-equalling third points classification. The mountains classification was won by Luis Herrera (Varta–Café de Colombia–Mavic). LeMond was the winner of the combination classification, Jozef Lieckens (Lotto) of the intermediate sprints classification, and Fabio Parra (Varta–Café de Colombia–Mavic) was the best rider who rode for the first time, winning the young rider classification. La Vie Claire won both the team and team points classifications.

Teams

The organisers of the Tour, the Société du Tour de France, a subsidiary of the Amaury Group,[2] were free to select which teams they invited for the event.[3] In June 1985, 21 teams had requested to start in the 1985 Tour.[4] Three Italian teams (Gis Gelati, Alpilatte–Olmo–Cierre, and Malvor–Bottecchia–Vaporella) withdrew, so the 1985 Tour started with 18 teams. Each team had 10 cyclists, so the 1985 Tour started with 180 cyclists.[5] Of these, 67 were riding the Tour de France for the first time.[6] The average age of riders in the race was 26.76 years,[7] ranging from the 20-year-old Miguel Induráin (Reynolds) to the 38-year-old Lucien Van Impe (Santini).[8] The Renault–Elf cyclists had the youngest average age while the riders on Verandalux–Dries–Nissan had the oldest.[9]

Two former Tour winners, van Impe (who won in 1976) and Joop Zoetemelk of Kwantum–Decosol–Yoko, who had won in 1980, both set a new record, as it was their fifteenth start in the race.[10]

The teams entering the race were:[5]

Pre-race favourites

.jpg)

Laurent Fignon (Renault–Elf) had won the 1984 Tour de France, his second victory in a row, by a substantial margin of more than ten minutes ahead of Bernard Hinault (La Vie Claire), a four-time winner of the Tour.[11] However, he was unable to defend his title, as an operation on an inflamed Achilles tendon left him sidelined.[12] According to Dutch newspaper Het Parool, Fignon missing the race was well received, considering that otherwise the race was expected to be as one-sided as the year before.[13]

In Fignon's absence, Hinault was considered the clear favourite to achieve his fifth overall victory,[14] which would draw him level with Jacques Anquetil and Eddy Merckx as record winner of the Tour.[13][15] Hinault himself commented ahead of the prologue: "If I sound sure of myself, it's because I am."[16][17] Earlier in the year, he had won the Giro d'Italia.[18] Hinault's team had been significantly strengthened for 1985, with the signings of Steve Bauer, Kim Andersen, and Bernard Vallet. The biggest addition to La Vie Claire's roster however was Greg LeMond. Having turned professional with Renault–Elf alongside Hinault and Fignon in 1981, he had enjoyed a steady rise in the cycling world, including winning the road world championship in 1983 and a third place in the previous year's Tour.[19] During that race, La Vie Claire's team owner Bernard Tapie had approached LeMond, offering him the highest-paid contract in cycling history to set him up as a successor to Hinault.[20][lower-alpha 1] LeMond was therefore considered "the other choice as a possible winner".[21] LeMond himself stated that he would work for Hinault, but that he did not doubt that Hinault would do the same for him should he lose his chances.[22] Equally, Hinault declared before the start that either himself or LeMond would win.[23] The amount of individual time trials, a total of 159 km (99 mi), was considered in Hinault's favour, since he excelled at the discipline.[13][24] Due to the race start in Brittany, Hinault's home region and the large amount of time trialling, commentators jokingly referred to the edition as the "Tour de Hinault".[25]

The third highly-ranked favourite was Phil Anderson (Panasonic–Raleigh), who had just won both the Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré and Tour de Suisse, the most important preparation races for the Tour.[15][23] Among the other favourites, there were mainly riders who were considered climbers, who ascended well up high mountains, but were inferior in time trials. These included Luis Herrera (Varta–Café de Colombia–Mavic), Robert Millar (Peugeot–Shell–Michelin),[lower-alpha 2] Peter Winnen (Panasonic–Raleigh), and Pedro Delgado (Seat–Orbea).[13] Other favourites included Ángel Arroyo (Zor–Gemeaz Cusin), Pedro Muñoz (Fagor), Claude Criquielion (Hitachi–Splendor–Sunair),[13] Stephen Roche (La Redoute), and Sean Kelly (Skil–Sem–Kas–Miko).[15] Kelly was ranked number one in the UCI Road World Rankings, after taking victory at Paris–Nice and winning three stages of the Vuelta a España.[27] His Irish compatriot Roche had displayed good form earlier in the year by winning the Critérium International and the Tour Midi-Pyrénées.[28] Charly Mottet (Renault–Elf), winner of the Tour de l'Avenir, considered the junior Tour de France, in 1984, was considered an outside bet for his team in the absence of team leader Fignon, given his young age.[29]

Route and stages

.jpg)

The 1985 Tour de France started on 28 June, and had one rest day, in Villard-de-Lans.[30] The race started in Brittany, Hinault's home region, with a prologue time trial in Plumelec. The route then headed north towards Roubaix, then south-east to Lorraine, then south through the Vosges and Jura into the Alps.[31] From there, the Tour passed through the Massif Central en route to the Pyrenees. After leaving the high mountains, the route moved north to Bordeaux, before travelling inland, with a time trial at Lac de Vassivière on the penultimate day, followed by a train transfer to Orléans for the final, ceremonial stage into Paris.[32] It was the first time since 1981 that the Tour was run clockwise around France.[33] The highest point of elevation in the race was 2,115 m (6,939 ft) at the summit of the Col du Tourmalet mountain pass on stage 17.[34][35]

The 1985 Tour was the last one to contain split stages, where two stages on the same day had the same number and were distinguished by an "a" and "b". Until 1991, there were still two stages held on the same day, but given separate stage numbers.[36] It was also the first time that two mountain stages were held on the same day, stages 18a and 18b in the Pyrenees.[37]

| Stage | Date | Course | Distance | Type | Winner | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | 28 June | Plumelec | 6 km (3.7 mi) | Individual time trial | ||

| 1 | 29 June | Vannes to Lanester | 256 km (159 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 2 | 30 June | Lorient to Vitre | 242 km (150 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 3 | 1 July | Vitre to Fougères | 73 km (45 mi) | Team time trial | La Vie Claire | |

| 4 | 2 July | Fougères to Pont-Audemer | 239 km (149 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 5 | 3 July | Neufchâtel-en-Bray to Roubaix | 224 km (139 mi) | Plain stage with cobblestones | ||

| 6 | 4 July | Roubaix to Reims | 222 km (138 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 7 | 5 July | Reims to Nancy | 217 km (135 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 8 | 6 July | Sarrebourg to Strasbourg | 75 km (47 mi) | Individual time trial | ||

| 9 | 7 July | Strasbourg to Épinal | 174 km (108 mi) | Hilly stage | ||

| 10 | 8 July | Épinal to Pontarlier | 204 km (127 mi) | Hilly stage | ||

| 11 | 9 July | Pontarlier to Morzine Avoriaz | 195 km (121 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 12 | 10 July | Morzine Avoriaz to Lans-en-Vercors | 269 km (167 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 13 | 11 July | Villard-de-Lans | 32 km (20 mi) | Individual time trial | ||

| 12 July | Villard-de-Lans | Rest day | ||||

| 14 | 13 July | Autrans to Saint-Étienne | 179 km (111 mi) | Hilly stage | ||

| 15 | 14 July | Saint-Étienne to Aurillac | 238 km (148 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 16 | 15 July | Aurillac to Toulouse | 247 km (153 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 17 | 16 July | Toulouse to Luz Ardiden | 209 km (130 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 18a | 17 July | Luz-Saint-Sauveur to Aubisque | 53 km (33 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 18b | Laruns to Pau | 83 km (52 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | |||

| 19 | 18 July | Pau to Bordeaux | 203 km (126 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 20 | 19 July | Montpon-Ménestérol to Limoges | 225 km (140 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 21 | 20 July | Lac de Vassivière | 46 km (29 mi) | Individual time trial | ||

| 22 | 21 July | Orléans to Paris (Champs-Élysées) | 196 km (122 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| Total | 4,109 km (2,553 mi)[41] | |||||

Race overview

Opening stages

Hinault laid down a claim towards his fifth Tour victory immediately, by winning the prologue time trial. LeMond suffered mechanical issues, as a jammed chain slowed him in the final section of the course. He nevertheless finished fifth, 21 seconds behind Hinault.[16] Eric Vanderaerden was second, four seconds slower than Hinault, ahead of Roche in third place.[42] Alfons De Wolf (Fagor) arrived five minutes late for his start and then lost another two minutes to Hinault, meaning that he was eliminated from the race before reaching the first stage proper, having missed the time limit.[43]

Rudy Matthijs (Hitachi–Splendor–Sunair) won the first stage from a bunch sprint, ahead of Vanderaerden, who with the help of time bonuses took over the race leader's yellow jersey. Maarten Ducrot (Kwantum–Decosol–Yoko) had highlighted the stage with a 205 km (127 mi) solo breakaway and held a maximum lead of 16 minutes, but was caught with 22 km (14 mi) to go.[44] Ángel Arroyo, second in the Tour of 1983, abandoned after just 123 km (76 mi) into the first stage.[45] Matthijs made it two stage wins in a row on the second stage, this time coming out on top in a sprint ahead of Sean Kelly.[46]

La Vie Claire won the stage 3 team time trial by over a minute ahead of the next-best team. Their team coach, Paul Köchli, had made the decision to fit faster wheels to the slower riders, balancing out the performance of the squad.[47] While Vanderaerden held on to the yellow jersey, courtesy of the time bonuses he had collected earlier, the eight riders behind him on general classification now came from La Vie Claire.[18] Hinault however was bothered by the large amount of reporters and photographers behind the finish line, punching one of them on the chin.[16] Stage 4 saw the first successful breakaway, with a seven-rider group finishing 46 seconds ahead of the main field. While Gerrit Solleveld (Kwantum–Decosol–Yoko) won the stage, Kim Andersen took the overall lead for La Vie Claire.[48] Future five-time Tour winner Miguel Induráin abandoned during stage 4.[30]

Stage 5 into Roubaix, which featured some cobbled roads, was won by Henri Manders (Kwantum–Decosol–Yoko). He had been in a breakaway with Teun van Vliet (Verandalux–Dries–Nissan), who had done most of the work on the front, before Manders left him about 20 km (12 mi) before the finish, as van Vliet developed spasms in his legs.[49] Stage 6 saw a controversial sprint finish in Reims. Kelly and Vanderaerden had battled hard for the victory, with the latter pushing Kelly towards the barriers, who pushed back with his arm. Vanderaerden crossed the line first and received the stage honours and the yellow jersey on the podium. Later however, the race jury decided to relegate both Kelly and Vanderaerden to the back of the field, giving the stage victory to Francis Castaing (Peugeot–Shell–Michelin), while the race lead remained with Andersen. LeMond, who had mixed himself into the sprint, was raised from fourth to second, giving him a twenty-second time bonus. This allowed him to move into third place in the general classification, two seconds ahead of Hinault.[48][50] With 51 km (32 mi) raced on stage 7, an eight-rider group attacked, including Ludwig Wijnants (Tönissteiner–TW Rock–BASF), but were brought back 27 km (17 mi) later. Luis Herrera was active later in the stage, establishing a breakaway after 193 km (120 mi). From this group, Wijnants, again in the breakaway, attacked with 3 km (1.9 mi) to go. Just as Herrera brought him back 2 km (1.2 mi) later, Wijnants attacked again to claim the stage win.[51]

Vosges and Jura

Stage 8 saw the first long individual time trial of the Tour. At 75 km (47 mi), it was the longest individual time trial in the Tour since 1960.[24] Bernard Hinault won the stage by a high margin, with second-placed Roche 2:20 minutes slower.[52] Hinault even caught and passed Sean Kelly, who had started two minutes ahead of him and proceeded to take another minute out of him. Third was Mottet, ahead of LeMond, who lost 2:34 minutes to Hinault.[48] While Hinault regained the race lead, LeMond was now his closest challenger, 2:32 minutes behind on the general classification, with Anderson and Roche already almost four minutes behind.[53] Dietrich Thurau (Hitachi–Splendor–Sunair) was given a one-minute time penalty for drafting behind Mottet. Angry at the decision, Thurau physically attacked the judge who had handed out the penalty, grabbing him by the throat, and was subsequently ejected from the race on stage 10.[25][54][lower-alpha 3]

The next stage to Épinal was won by Maarten Ducrot, 38 seconds ahead of René Bittinger (Skil–Sem–Kas–Miko). Jeronimo Ibañez Escribano (Seat–Orbea) was taken to hospital, following a crash 8 km (5.0 mi) from the finish.[56] On stage 10, Jørgen V. Pedersen won the day for Carrera–Inoxpran in a sprint finish, beating Johan Lammerts (Panasonic–Raleigh) into second place. Hinault finished 15th and retained his lead in the overall standings.[57] Paul Sherwen (La Redoute) was involved in a crash just 1 km (0.62 mi) into the stage and suffered throughout, reaching the finish more than an hour behind Pedersen. Since he arrived so late, he had to traverse in between spectators who thought no more riders would come across the route. He was well outside the time limit, but the race jury, against the advice of the race director, decided to allow him to start the next stage, naming his "courage" after his early fall as the reason for their decision.[58][59]

Alps

.jpg)

The race entered the high mountains on stage 11, with the first leg in the Alps to Avoriaz. The route crossed the summits of the Pas de Morgins and Le Corbier before arriving in Morzine for the final ascent. Hinault strengthened his claim on the overall victory by escaping early with Luis Herrera, who by now was too far down in the general classification to be a threat. Instead, he collected the points for the mountains classification, a lead which he would hold until the end of the race. Herrera also won the stage, seven seconds ahead of Hinault. LeMond lost 1:41, coming in fifth in a group with Delgado and Fabio Parra (Varta–Café de Colombia–Mavic). Hinault's lead therefore increased to exactly four minutes on second-placed LeMond in the overall standings.[60][61]

Even though stage 12 featured seven categorised climbs, it saw no changes on the top of the general classification,[60] as Parra and Herrera fought out the victory in between teammates. This time, it was Parra who emerged the winner, on the same time as Herrera. Kelly and Niki Rüttimann (La Vie Claire) followed 38 seconds down, one second ahead of the group containing the other favourites, led home by Roche.[62] During the stage, Joël Pelier (Skil–Sem–Kas–Miko), riding his first Tour, had followed Herrera, thinking he was joining a breakaway, not realising that Herrera was only sprinting for mountain points. Hinault, who was generally accepted as the patron, meaning the most influential rider, was unhappy with the acceleration in the field, as he wanted the tempo to remain slow. This led to an altercation between the two, with Hinault driving up to Pelier and to complain.[63][64][lower-alpha 4]

Weakened by his attacking riding style, Hinault placed only second in the mountain time trial to Villard-de-Lans, about a minute behind Vanderaerden. Yet, his advantage over LeMond, who again had mechanical issues, increased to 5:23 minutes on the general classification.[60] Roche lost 16 seconds to Hinault, Anderson 24 seconds and Kelly 35 seconds. Roche remained the closest competitor to the La Vie Claire duo, sitting third overall, 6:08 minutes behind Hinault, with Kelly fourth, at 6:35 minutes. Anderson was sixth, behind Bauer.[66]

Transition through Massif Central

Following the only rest day of the Tour, stage 14 took the riders to Saint-Étienne in the Massif Central. The stage, following a hilly route, saw Luis Herrera attack again and gain more points for the mountains classification. Although he crashed on the final descent of the day, he prevailed to reach the finish line first, soaked in blood, 47 seconds ahead of a select group of riders containing LeMond.[67] Hinault followed in a group almost two minutes later. As they approached the finish, Bauer's rear wheel hit a piece of traffic furniture. As his bike moved sideways, it touched Anderson's, who crashed and brought down Hinault with him. The latter suffered a broken nose, but was able to finish the stage. As the accident had occurred within the final kilometre, the time he lost in the crash was not counted. However, Hinault rode the rest of the Tour with a stitched nose and two black eyes, caused by his sunglasses breaking when he fell.[64][68][69] As a result of LeMond finishing ahead of him, Hinault's overall lead was cut down to 3:32 minutes.[67]

Stage 15 was another transition stage. Hennie Kuiper (Verandalux–Dries–Nissan), winner of Milan–San Remo earlier in the year, did not take the start. Pedro Muñoz abandoned the race after 30 km (19 mi). Jean-Claude Bagot of Fagor escaped on the third climb of the day, after 96 km (60 mi). After he was recaptured, another attack went, containing Joël Pelier. Hinault, suffering from his injuries, was unhappy with the accelerations and brought the escape group back himself, not least due to the participation of Pelier. After 134 km (83 mi), Eduardo Chozas (Reynolds) attacked on a downhill section and managed to get away from the peloton. By the time he crossed the summit of the Col d'Entremont after 180 km (110 mi), his lead had increased to over ten minutes. 15 km (9.3 mi) from the finish. the gap had increased to over 11 minutes, while Ludo Peeters (Kwantum–Decosol–Yoko) escaped from the main field. At the finish, Chozas took victory, 9:51 minutes ahead of Peeters, who just held off the group of favourites, led by Kelly. Hinault retained the race lead, while Chozas rose to seventh overall.[70]

Another stage with minor categorised climbs followed the next day. Frédéric Vichot (Skil–Sem–Kas–Miko) broke clear of the field after 38 km (24 mi), building a maximum lead of more than twenty minutes. As he approached the finish, his advantage decreased significantly, but he managed to win the stage, 3:12 minutes ahead of Mottet and Bontempi, as Hinault remained the leader of the race overall.[71]

Pyrenees

–Greg LeMond, describing his view of the controversial stage 17[72]

Congestion in his broken nose had led to a bronchitis for Hinault, severely impacting his ability to perform. He was therefore on the back foot as the race entered the Pyrenees on stage 17. On the Col du Tourmalet, Renault–Elf set a high tempo, putting Hinault into difficulty. Pedro Delgado later recalled that he saw Hinault yelling at Herrera, at which point he decided to attack.[73] With Delgado went Roche and LeMond, as well as Parra. Early leader Pello Ruiz Cabestany (Seat–Orbea) led over the top of the Tourmalet, 1:18 minutes ahead of Delgado, followed by LeMond, Roche, and Parra two minutes down.[74] As they approached the final ascent to Luz Ardiden, LeMond and Roche were in front. LeMond asked his team car about the gap to Hinault. Koechli told LeMond that Hinault was only 45 seconds behind him and that he was not allowed to work with Roche, in order not to endanger La Vie Claire standing first and second on the general classification. He was told to hold station or attack and drop Roche. The latter heard the conversation between LeMond and his team car and remained alert, therefore, both cancelled each other out and allowed other riders to catch back up. When LeMond saw that Hinault was not among them, he began to suspect that the gap he had been told was not correct.[75] Delgado attacked from the main group and won the stage. LeMond eventually finished fifth, 2:52 minutes behind, and gained little over a minute on Hinault.[76][77][78] At the finish, LeMond was visibly angry when interviewed by American television, saying that he felt betrayed by his team of a chance to win the Tour.[79] In the general classification, Hinault remained in front, with LeMond 2:25 minutes behind.[77] Views on the stage differ. LeMond describes how he was ready to quit the Tour that night, being severely disappointed by his team's refusal to let him work with Roche in order to win the Tour. Hinault meanwhile maintains that there were no bad feelings inside La Vie Claire during the 1985 Tour and that it was a clear case of not attacking a teammate who has the race lead.[80] Later the same day, team owner Tapie and Hinault convinced LeMond to continue riding by assuring him that the year after, Hinault would work for LeMond.[81] LeMond emerged from the meeting with a different public statement, telling the press that he got carried away after the finish and that he would continue to work for Hinault.[78]

Stage 18a, which was held in the morning, had a summit finish on the Col d'Aubisque. Roche attacked on the final ascent and won the stage, taking one-and-a-half minutes out of Hinault's lead.[52] According to LeMond, Hinault was suffering so badly this time that he had to push his teammate in order to conserve the race lead.[81][82] Stage 18b in the afternoon was won by Roche's La Redoute teammate Régis Simon, who won a two-man sprint to the line against Álvaro Pino (Zor–Gemeaz Cusin).[83] After the two split stages, Hinault's lead over LeMond stood at 2:13 minutes, with Roche in third, 3:30 minutes behind.[84]

Final stages

_(cropped).jpg)

With only one time trial to come, victory appeared all but secure for Hinault. Speaking to journalist Samuel Abt of The New York Times, five-time Tour winner Jacques Anquetil declared that he and Eddy Merckx would "accept him in our club with pleasure".[85] Stage 19 to Bordeaux remained uneventful until about 30 km (19 mi) to the finish, when several riders tried, but failed, to escape. The race then settled for a bunch sprint, won by Vanderaerden ahead of Kelly by a very small margin. It was the first time during this Tour that the entire field, still 145 riders strong, reached the finish together.[86] The following day, Johan Lammerts achieved the third stage victory for the Panasonic–Raleigh team. He had broken away with four other riders with 35 km (22 mi) to go and went clear of them 9 km (5.6 mi) from the finish to win by 21 seconds ahead of Andersen. LeMond gained several seconds through bonuses at intermediate sprints, closing the gap to Hinault to 1:59 minutes.[87]

On the penultimate day of the Tour, stage 21 saw the final time trial, around Lac de Vassivière near Limoges. LeMond did not incur any mechanical difficulties this time and won the stage, five seconds faster than Hinault. It was not only the first stage win for LeMond, but the first for a rider from the United States.[81] After the stage, LeMond said: "Now I know I can beat Hinault. I know I can win the Tour de France."[88] Third place went to Anderson, who finished 31 seconds slower than LeMond, with Kelly in fourth, 54 seconds adrift, five seconds faster than Roche.[89]

The final stage into Paris was, per tradition, a ceremonial affair, with no attacks to alter the general classification.[90] In the final sprint, Rudy Matthijs took his third stage victory,[91] with Sean Kelly finishing in second place for the fifth time during this Tour.[92] Hinault finished safely in the field to win his fifth Tour de France,[93] putting him equal with Anquetil and Merckx as record winner of the event, as well as securing his second Giro-Tour double.[94] During the final stage, Pedro Delgado used the small categorised climbs along the route to move past Robert Millar into second place in the mountains classification, ensuring his team the prize money that went with it.[95][lower-alpha 5]

Hinault's final victory margin over LeMond was 1:42 minutes.[96] Roche rounded out the podium in third place, 4:29 minutes behind. His compatriot Kelly finished fourth overall, at 6:26 minutes, ahead of Anderson.[97] The average speed of the race was 36.391 km/h (22.612 mph), compared to 35.882 km/h (22.296 mph) the year before.[98] Five teams finished the Tour with all ten riders still in the race: La Vie Claire, Skil–Sem–Kas–Miko, Kwantum–Decosol–Yoko, Peugeot–Shell–Michelin, and Panasonic–Raleigh.[99]

Classification leadership and minor prizes

There were several classifications in the 1985 Tour de France, six of them awarding jerseys to their leaders.[100] The most important was the general classification, calculated by adding each cyclist's finishing times on each stage. The cyclist with the least accumulated time was the race leader, identified by the yellow jersey; the winner of this classification is considered the winner of the Tour.[101] There were two ways to gain time bonuses, which subtracted seconds from a rider's overall time. One was at stage finishes, where the first three riders across the line received 30, 20, and 10 seconds bonus respectively. The split stages 18a and 18b awarded full time bonuses each.[102] Secondly, riders were able to gain 10, 6, and 3 seconds bonus for the first three to cross the line at intermediate sprints. Unlike the previous year, where these were only given out during flat stages, the time bonuses at intermediate sprints were awarded during every road stage of the 1985 Tour.[103]

Additionally, there was a points classification, where cyclists were given points for finishing among the best in a stage finish. The cyclist with the most points led the classification, and was identified with a green jersey.[104] The system for the points classification was changed for the 195 Tour: in previous years, more points were earned in flat stages than in mountain stages, which gave sprinters an advantage in this classification; while in 1985, all stages gave 25 points for the winner, down to 1 point for 25th placce.[105][106] Unlike in many other years, between 1984 and 1986, intermediate sprints did not award points for this classification.[107] Sean Kelly won the classification for a record-equalling third time.[92] His 434 points were 69.4% of the maximum possible amount obtainable, a record as of 2019.[108]

There was also a mountains classification. The points system for the classification was changed: mountains in the toughest categories gave more points, to reduce the influence of the minor hills on this classification.[105] The organisation had categorised some climbs as either hors catégorie, first, second, third, or fourth-category; points for this classification were won by the first cyclists that reached the top of these climbs first, with more points available for the higher-categorised climbs.[109] Hors catégorie climbs awarded 40 points to the first rider across, down to 1 point for the 15th rider. First-category mountains awarded 30 points to the first rider to reach the top, with the other three categories awarding 20, 7, and 4 points respectively to the first man across the summit.[110] The cyclist with the most points led the classification, and wore a white jersey with red polka dots.[109] Luis Herrera won the mountains classification.[30]

The combination jersey for the combination classification was introduced in 1985.[105] This classification was calculated as a combination of the other classifications:[111] a first place in one of the classifications awarded 25 points, down to 1 point for 25th place. Only the general, mountains, points, and intermediate sprint classifications were included here.[112] The winner of this classification was Greg LeMond.[113]

Another classification was the young rider classification. This was decided the same way as the general classification, but only riders that rode the Tour for the first time were eligible, and the leader wore a white jersey.[111][114] The winner of this classification was Fabio Parra, who finished in eighth place in the general classification.[30]

The sixth individual classification was the intermediate sprints classification. This classification had similar rules as the points classification, but only points were awarded on intermediate sprints. Its leader wore a red jersey.[115] The intermediate sprints awarded more points the more the Tour progressed, from 3,2, and 1 points for the first three riders across during stages 1 to 5 to 12,8, and 4 points respectively during the last five stages.[116] The classification was won by Jozef Lieckens (Lotto).[117]

For the team classification, the times of the best three cyclists per team on each stage were added; the leading team was the team with the lowest total time. The riders in the team that led this classification were identified by yellow caps.[115] There was also a team points classification. Cyclists received points according to their finishing position on each stage, with the first rider receiving one point. The first three finishers of each team had their points combined, and the team with the fewest points led the classification. The riders of the team leading this classification wore green caps.[115] La Vie Claire led both classifications after the prologue as well as from stage 8 until the finish.[118]

In addition, there was a combativity award, in which a jury composed of journalists gave points after each mass-start stage to the cyclist they considered most combative. The split stages each had a combined winner.[119] At the conclusion of the Tour, Maarten Ducrot won the overall super-combativity award, also decided by journalists.[30] The Souvenir Henri Desgrange was given in honour of Tour founder Henri Desgrange to the first rider to pass the summit of the Col du Tourmalet on stage 17. This prize was won by Pello Ruiz Cabestany.[120]

The 1985 Tour was the last to feature what was called "flying stages", introduced in 1977: on stages 4 and 11, there was a finish line at the midway point of the course, which was treated as a stage finish but the race continued uninterrupted afterwards. Kim Andersen was the first to cross the line on stage 4, while Eric Vanderaerden took the honours on stage 11. They received the same prizes as regular stage winners, including prize money, time bonuses and points for the points classification, but the times were not taken for the general classification. Officially, they were also supposed to be counted as stage victories, but the public did not accept the concept and both are today not included in stage winner statistics and the idea was scrapped the following year.[121]

In total, the Tour organisers paid out 3,003,050 French francs in prize money, with 40,000 and an apartment valued at 120,000 Francs given to the winner of the general classification.[122]

- In stage 21, Greg LeMond wore the technicolor jersey.

Final standings

| Legend | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Denotes the winner of the general classification | Denotes the winner of the points classification | ||

| Denotes the winner of the mountains classification | Denotes the winner of the young rider classification | ||

| Denotes the winner of the combination classification | Denotes the winner of the intermediate sprints classification | ||

General classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | La Vie Claire | 113h 24' 23" | |

| 2 | La Vie Claire | + 1' 42" | |

| 3 | La Redoute | + 4' 29" | |

| 4 | Skil–Sem–Kas–Miko | + 6' 26" | |

| 5 | Panasonic–Raleigh | + 7' 44" | |

| 6 | Seat–Orbea | + 11' 53" | |

| 7 | Varta–Café de Colombia–Mavic | + 12' 53" | |

| 8 | Varta–Café de Colombia–Mavic | + 13' 35" | |

| 9 | Reynolds | + 13' 56" | |

| 10 | La Vie Claire | + 14' 57" |

Points classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Skil–Sem–Kas–Miko | 434 | |

| 2 | La Vie Claire | 332 | |

| 3 | La Redoute | 279 | |

| 4 | La Vie Claire | 266 | |

| 5 | Panasonic–Raleigh | 258 | |

| 6 | Panasonic–Raleigh | 244 | |

| 7 | Kwantum–Decosol–Yoko | 199 | |

| 8 | Varta–Café de Colombia–Mavic | 195 | |

| 9 | Tönissteiner–TW Rock–BASF | 192 | |

| 10 | Seat–Orbea | 156 |

Mountains classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Varta–Café de Colombia–Mavic | 440 | |

| 2 | Seat–Orbea | 274 | |

| 3 | Peugeot–Shell–Michelin | 270 | |

| 4 | La Vie Claire | 214 | |

| 5 | Varta–Café de Colombia–Mavic | 190 | |

| 6 | La Vie Claire | 165 | |

| 7 | Santini | 136 | |

| 8 | Varta–Café de Colombia–Mavic | 133 | |

| 9 | La Redoute | 130 | |

| 10 | Reynolds | 113 |

Young rider classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Varta–Café de Colombia–Mavic | 113h 37' 58" | |

| 2 | Reynolds | + 21" | |

| 3 | La Vie Claire | + 1' 22" | |

| 4 | Peugeot–Shell–Michelin | + 4' 10" | |

| 5 | Zor–Gemeaz Cusin | + 8' 00" | |

| 6 | La Redoute | + 25' 41" | |

| 7 | Zor–Gemeaz Cusin | + 26' 03" | |

| 8 | Renault–Elf | + 29' 22" | |

| 9 | Reynolds | + 32' 18" | |

| 10 | Zor–Gemeaz Cusin | + 32' 37" |

Combination classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | La Vie Claire | 91 | |

| 2 | Skil–Sem–Kas–Miko | 85 | |

| 3 | La Vie Claire | 76 | |

| 4 | La Redoute | 63 | |

| 5 | Varta–Café de Colombia–Mavic | 62 | |

| 6 | Seat–Orbea | 60 | |

| 7 | Reynolds | 57 | |

| 8 | La Vie Claire | 56 | |

| 9 | La Vie Claire | 51 | |

| 10 | Kwantum–Decosol–Yoko | 47 |

Intermediate sprints classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lotto | 162 | |

| 2 | Reynolds | 67 | |

| 3 | Skil–Sem–Kas–Miko | 59 | |

| 4 | La Vie Claire | 54 | |

| 5 | La Vie Claire | 51 | |

| 6 | Skil–Sem–Kas–Miko | 47 | |

| 7 | Renault–Elf | 38 | |

| 8 | Varta–Café de Colombia–Mavic | 32 | |

| 9 | Zor–Gemeaz Cusin | 32 | |

| 10 | Kwantum–Decosol–Yoko | 26 |

Team classification

| Rank | Team | Time |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | La Vie Claire | 340h 21' 09" |

| 2 | Panasonic–Raleigh | + 27' 10" |

| 3 | Peugeot–Shell–Michelin | + 40' 54" |

| 4 | Skil–Sem–Kas–Miko | + 46' 51" |

| 5 | La Redoute | + 53' 57" |

| 6 | Varta–Café de Colombia–Mavic | + 1h 05' 24" |

| 7 | Reynolds | + 1h 11' 28" |

| 8 | Zor–Gemeaz Cusin | + 1h 25' 42" |

| 9 | Renault–Elf | + 1h 26' 54" |

| 10 | Carrera–Inoxpran | + 1h 30' 18" |

Team points classification

| Rank | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | La Vie Claire | 1095 |

| 2 | Panasonic–Raleigh | 1268 |

| 3 | Skil–Sem–Kas–Miko | 1475 |

| 4 | Peugeot–Shell–Michelin | 1579 |

| 5 | La Redoute | 1727 |

| 6 | Lotto | 1802 |

| 7 | Hitachi–Splendor–Sunair | 1832 |

| 8 | Lotto | 1858 |

| 9 | Tönissteiner–TW Rock–BASF | 2461 |

| 10 | Renault–Elf | 2471 |

Aftermath

Hinault reiterated his promise to work for LeMond the following year several times during the final part of the 1985 Tour. Following the time trial on the penultimate day, he publicly stated in an interview with French cycling magazine Miroir du Cyclisme: "I'll stir things up to help Greg win, and I'll have fun doing it. That's a promise."[131] On the victory podium in Paris, he leaned over to LeMond, telling him: "Next year, it's you", repeating the pledge again during the celebration dinner of La Vie Claire that same evening.[132] Public opinion saw Hinault and LeMond as good friends. The sports newspaper L'Equipe ran a cartoon on the day of the final stage, showing Hinault on a bicycle and LeMond next to him on a child's scooter, with Hinault saying "Because you've been so good, I'll take you along next year on my handlebars", to which LeMond replied: "Thanks, Uncle Bernard."[133] His first Tour victory the following year did not come to LeMond as easily as these pledges and jokes indicated. Hinault attacked several times during the 1986 Tour de France, only conceding defeat after the last time trial.[134] LeMond was frustrated with the apparent unwillingness by Hinault to honour the deal, saying: "He made promises to me he never intended to keep. He made them just to relieve the pressure on himself."[135] The rivalry between Hinault and LeMond in both the 1985 and 1986 Tours was subject of the documentary Slaying the Badger, part of ESPN's series 30 for 30. Based on the book by the same name by journalist Richard Moore, it premiered on 22 July 2014.[136]

In previous years, cyclists tied their shoes to their pedals with toe-clips, allowing them to not only push the pedals down but also pull them up. In 1985, Hinault used clip-ins (clipless pedals), which allowed the shoes to snap into the pedal. His victory in this Tour made these clip-ins popular.[137]

There was some criticism that the time trials were too important. If the time trials would have not counted towards the general classification, the result would have been as follows:[138]

| Rank | Name | Team | Time gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Varta–Café de Colombia–Mavic | ||

| 2 | Seat–Orbea | + 16" | |

| 3 | La Vie Claire | + 2' 28" | |

| 4 | Varta–Café de Colombia–Mavic | + 2' 52" | |

| 5 | La Redoute | + 4' 22" | |

| 6 | Reynolds | + 4' 27" | |

| 7 | Skil–Sem–Kas–Miko | + 4' 32" | |

| 8 | La Vie Claire | + 4' 47" | |

| 9 | Peugeot–Shell–Michelin | + 6' 21" | |

| 10 | Panasonic–Raleigh | + 6' 55" |

The total length of the time trials reduced from 223 kilometres (139 mi) in 1985 to 180 kilometres (110 mi) in 1986.[139] Tour director Félix Lévitan felt after the 1985 Tour de France that the race had been too easy, and made the course in 1986 extra difficult, including more mountain climbs than before.[140]

This was the last year that the Tour de France was actively managed by Jacques Goddet, who had taken over as race director from the race's founder, Henri Desgrange, in 1936.[94]

Doping

After every stage, around four cyclists were selected for doping controls. None of these cyclists tested positive for performance-enhancing drugs.[141][142] After the end of the Tour, world champion Claude Criquielion, who had finished 18th overall, was involved in a doping controversy. At the national championship race before the Tour, he had tested positive for Pervitin, but received no repercussions. The head of the laboratory at Ghent University, which had administered the analysis, subsequently resigned his post in the Medical Commission of the Belgian Cycling Association (KBWB) in protest.[143]

Notes

- LeMond was paid $225,000 in his first year, §260,000 in the second, and $300,000 in his third. A promise of royalty payments for clipless pedals created by Look, another company owned by Tapie, never materialised.[20]

- Robert Millar later in life had a gender transition and is now known as Philippa York.[26] For the purpose of this article, her name and gender from 1985 are used.

- Thurau claimed that the judge, Raymond Trine from Belgium, held a grudge against him, having already handed out a penalty for doping at the 1980 German championships which was later overturned. He also held the opinion that if he were to be penalised, Mottet should be as well, who he claimed had drafted as well.[55]

- The split between Pelier and Hinault lasted over a year, until they became friends when Pelier supported Hinault during the 1986 World Championships. During the 1989 Tour de France, when Hinault was working as a consultant to the Tour organisation, Pelier was in an eventually successful solo breakaway, on stage 6 to Futuroscope. Pelier was surprised to find that Hinault drove up next to him in the organisers' car and cheered him on.[65]

- The magazine Cycling described Delgado's attack as the "final humiliation" for Millar, who had lost the 1985 Vuelta a España to Delgado in a controversial penultimate stage, where Delgado had escaped and was aided by Spanish compatriots to dislodge Millar of overall victory.[95]

References

- Heijmans & Mallon 2011, p. 95.

- Woodland 2007, p. 335.

- van den Akker 2018, p. 17.

- "Record-aantal ploegen in Tour". Nieuwsblad van het Noorden (in Dutch). Koninklijke Bibliotheek. 15 June 1985. p. 23. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1985 – The starters". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Tour de France 1985 – Debutants". ProCyclingStats. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "Tour de France 1985 – Peloton averages". ProCyclingStats. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "Tour de France 1985 – Youngest competitors". ProCyclingStats. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "Tour de France 1985 – Average team age". ProCyclingStats. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "Record Zoetemelk". Leeuwarder Courant (in Dutch). 26 June 1985. Retrieved 31 March 2020 – via Delpher.

- Fotheringham 2015, pp. 232–239.

- McGann & McGann 2008, pp. 153–155.

- Asbroek, Harry Ten (24 June 1985). "Kopmannen dringen om Fignons erfenis" [Leaders push for Fignon's legacy]. Het Parool (in Dutch). p. 15. Retrieved 2 April 2020 – via Delpher.

- Van Gucht 2015, p. 164.

- Oudshoorn, Erik; de Vries, Guido (27 June 1985). "Hinault kan record Merckx en Anquetil evenaren in Tour de France" [Hinault can match Merckx and Anquetil record in Tour de France]. NRC Handelsblad (in Dutch). p. 8. Retrieved 2 April 2020 – via Delpher.

- Moore 2011, p. 150.

- Abt 1990, p. 93.

- McGann & McGann 2008, p. 155.

- Fotheringham 2015, p. 247.

- Moore 2011, pp. 137–139.

- McGann & McGann 2008, p. 153.

- Ceulen, Bennie (22 June 1985). "Greg LeMond: "Bernard Hinault is de boss..."" [Greg LeMond: "Bernard Hinault is the boss..."]. Limburgsch Dagblad (in Dutch). p. 21. Retrieved 2 April 2020 – via Delpher.

- "Hinault: "Lemond of ik winaar"" [Hinault: "LeMond or me will win"]. Leeuwarder Courant (in Dutch). Geassocieerde Pers Diensten. 26 June 1985. p. 19. Retrieved 2 April 2020 – via Delpher.

- Van Gucht 2015, p. 172.

- "Prügel im Endkampf" [Terminal-state birching]. Der Spiegel (in German) (30/1985). 22 July 1985. pp. 123–129. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Fotheringham, William (6 July 2017). "Philippa York: 'I've known I was different since I was a five-year-old'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Ryan 2018, p. 166.

- Roche & Cossins 2012, pp. 54–55.

- Ouwerkerk, Peter (26 June 1985). "Charly Mottet en de tendinitis" [Charly Mottet and the tendonitis]. Het Vrije Volk (in Dutch). p. 22. Retrieved 2 April 2020 – via Delpher.

- Augendre 2016, p. 76.

- Wheatcroft 2013, p. 255.

- Bacon 2014, p. 179.

- van den Akker 2018, p. 12.

- Augendre 2016, p. 188.

- "Ronde van Frankrijk 85" [Tour de France 85]. Limburgs Dagblad (in Dutch). 27 June 1985. p. 21 – via Delpher.

- van den Akker 2018, p. 129.

- Ryan 2018, p. 169.

- "72ème Tour de France 1985" (in French). Mémoire du cyclisme. Archived from the original on 19 August 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- Zwegers, Arian. "Tour de France GC top ten". CVCCBike.com. Archived from the original on 10 June 2009. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1985 – The stage winners". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Augendre 2016, p. 110.

- "Bernard Hinault winaar Proloog Tour de France" [Bernard Hinault winner - prologue of the Tour de France]. Amigoe (in Dutch). 29 June 1985. p. 9 – via Delpher.

- Wheatcroft 2013, pp. 254–255.

- "Rudy Matthijs wint 1e etappe" [Rudy Matthijs wins first stage]. Amigoe (in Dutch). 29 June 1985. p. 9 – via Delpher.

- "Debâcle Arroyo" [Debacle Arroyo]. Leeuwarder Courant (in Dutch). 1 July 1985. p. 14 – via Delpher.

- "Uitslagen van Tour" [Results of the Tour]. Leeuwarder Courant (in Dutch). 1 July 1985. p. 14 – via Delpher.

- Fotheringham 2015, p. 256.

- McGann & McGann 2008, p. 156.

- de Vries, Guido (4 July 1985). "Raas dirigeert Manders naar omstreden zege" [Raas directs Manders to a controversial victory]. NRC Handelsblad (in Dutch). p. 19 – via Delpher.

- Ryan 2018, pp. 167–168.

- "Pelicula de la etapa" [Movie of the stage] (PDF). Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 6 July 1985. p. 25.

- Rendell 2008, p. 216.

- Fotheringham 2015, pp. 256–257.

- "Thurau, expulsado de carrera" [Thurau, expelled from the race] (PDF). Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 9 July 1985. p. 30.

- Abt 2005, p. 28.

- "Dutchman Wins the Ninth Leg". Los Angeles Times. Épinal. Associated Press. 8 July 1985. p. 36 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Hinault retains cycling lead". Austin American-Statesman. Pontarlier. 9 July 1985. p. 20 – via Newspapers.com.

- Burgess, Charles (9 July 1985). "Sherwen's Courage Wins Judges' Vote". The Guardian. p. 29. Retrieved 24 April 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Abt 2005, pp. 28–29.

- McGann & McGann 2008, p. 157.

- Fotheringham 2015, p. 257.

- "Parra battles teammate to win 12th leg of Tour". The Ottawa Citizen. Lans-en-Vercors. United Press International. 11 July 1985. p. 66 – via Newspapers.com.

- Moore 2014, pp. 53–54.

- Fotheringham 2015, p. 259.

- Moore 2014, p. 54.

- "Vanderaerden heeft wind mee en wint verrassend de tijdrit" [Vanderaerden has a tailwind and surprisingly wins the time trial]. Leeuwarder Courant (in Dutch). Villard-de-Lans. Geassocieerde Pers Diensten. 12 July 1985. p. 6 – via Delpher.

- "Top Riders Injured in Tour de France". Reno Gazette-Journal. Saint-Étienne. Associated Press. 14 July 1985. p. 32 – via Newspapers.com.

- Moore 2011, pp. 152–153.

- Rendell 2008, p. 214.

- "Pelicula de la etapa" [Movie of the Stage] (PDF). Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 15 July 1985. p. 3.

- "Pelicula de la etapa" [Movie of the Stage] (PDF). Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 16 July 1985. p. 25.

- Moore 2011, p. 159.

- Fotheringham 2015, pp. 259–260.

- "Pelicula de la etapa". Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 17 July 1985. p. 4. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- de Visé 2019, pp. 124–127.

- Fotheringham 2015, p. 261.

- McGann & McGann 2008, p. 160.

- Abt 1990, p. 94.

- Moore 2011, pp. 158–159.

- Moore 2011, pp. 159–160.

- de Visé 2019, p. 128.

- Moore 2011, p. 158–160.

- "Régis Simon even uit schaduw broers" [Régis Simon out of his brothers' shadows]. Het Vrije Volk (in Dutch). 18 July 1985. p. 15. Retrieved 23 April 2020 – via Delpher.

- Moore 2011, p. 160.

- Abt, Samuel (18 July 1985). "Victory Within Reach of Weary Hinault". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Burgess, Charles (19 July 1985). "Second Again for Maverick Kelly". The Guardian. p. 24. Retrieved 24 April 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Burgess, Charles (20 July 1985). "Paris Awaits Hinault". The Guardian. p. 12. Retrieved 24 April 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Moore 2011, p. 161.

- "Stage 21 to LeMond, but Hinault Holds Lead". The Boston Globe. United Press International. 21 July 1985. p. 77. Retrieved 24 April 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Woodland 2007, p. 84.

- "Matthijs lacht ook op Champs Elysées" [Matthijs laughs on the Champs Elysées as well]. Het Parool (in Dutch). 22 July 1985. p. 15. Retrieved 24 April 2020 – via Delpher.

- Ryan 2018, p. 171.

- Smith 2009, p. 79.

- McGann & McGann 2008, p. 162.

- Moore 2008, pp. 198–199.

- Fife 2000, p. 55.

- McGann & McGann 2008, p. 161.

- Laget et al. 2013, pp. 230–232.

- van den Akker 2018, p. 39.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, pp. 452–455.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, pp. 452–453.

- van den Akker 2018, pp. 128–129.

- van den Akker 2018, pp. 183–184.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, pp. 453–454.

- "Ruim ton voor winnaar" [More Than a Ton for the Winner]. Het Vrije Volk (in Dutch). Koninklijke Bibliotheek. 28 June 1985. p. 21. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- van den Akker 2018, p. 154.

- van den Akker 2018, p. 180.

- van den Akker 2018, p. 158.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, p. 454.

- van den Akker 2018, p. 163.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, pp. 454–455.

- van den Akker 2018, p. 187.

- Laget et al. 2013, p. 232.

- van den Akker 2018, p. 174.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, p. 455.

- van den Akker 2018, p. 181.

- "Clasificaciones oficiales". Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 22 July 1985. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- van den Akker 2018, p. 190.

- van den Akker 2018, pp. 211–216.

- "Greg Lemond gevangen in keurslijf" [Greg Lemond caught in straitjacket]. Het Vrije Volk (in Dutch). 17 July 1985. p. 17 – via Delpher.

- van den Akker 2018, p. 79.

- Woodland 2007, p. 313.

- "Dag na dag" [Day to day]. Gazet van Antwerpen (in Dutch). 22 July 1985. p. 23. Archived from the original on 14 February 2019.

- Martin 1985, pp. 124–125.

- van den Akker, Pieter. "Informatie over de Tour de France van 1985" [Information about the Tour de France from 1985]. TourDeFranceStatistieken.nl (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- "Tour in cijfers". Leidsch Dagblad (in Dutch). 22 July 1985. p. 10 – via Regionaal Archief Leiden.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1985 – Stage 22 Orléans > Paris". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Tour de France". Het Parool (in Dutch). 22 July 1985. p. 14 – via Delpher.

- van den Akker, Pieter. "Stand in het jongerenklassement – Etappe 22" [Standings in the youth classification – Stage 22]. TourDeFranceStatistieken.nl (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- van den Akker, Pieter. "Sprintdoorkomsten in de Tour de France 1985" [Sprint results in the Tour de France 1985]. TourDeFranceStatistieken.nl (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 25 April 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- Moore 2011, p. 168.

- de Visé 2019, pp. 128–129.

- Abt 1990, p. 96.

- McGann & McGann 2008, pp. 162–170.

- Van Gucht 2015, p. 186.

- "Slaying the Badger – ESPN Films: 30 for 30". ESPN. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Heijmans & Mallon 2011, p. 157.

- Nelissen, Jean (22 July 1985). "Hinault populairder dan ooit" [Hinault more popular than ever]. Leidsche Courant (in Dutch). Regionaal Archief Leiden. p. 9. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- "73ème Tour de France 1986" (in French). Mémoire du cyclisme. Archived from the original on 28 August 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- "Hinault boos op Tourbaas Lévitan" [Hinault angry with Tour boss Lévitan]. Leidsch Dagblad (in Dutch). Regionaal archief Leiden. 9 October 1985. p. 15. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- "Geen nieuws van het dopingfront" [No news from the doping front]. Leidsche Courant (in Dutch). Regionaal Archief Leiden. 22 July 1985. p. 11. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- van den Akker 2018, p. 90.

- "Affaire-Criquelion krijgt een staartje" [Affair Criquelion gets a tail]. De Volkskrant (in Dutch). 8 August 1985. p. 8. Retrieved 2 April 2020 – via Delpher.

Bibliography

- Abt, Samuel (1990). LeMond: The Incredible Comeback. London: Stanley Paul. ISBN 978-0-09-174874-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Abt, Samuel (2005). Up the Road: Cycling's Modern Era from LeMond to Armstrong. Boulder, CO: VeloPress. ISBN 1-931382-78-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Augendre, Jacques (2016). Guide historique [Historical guide] (PDF). Tour de France (in French). Paris: Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bacon, Ellis (2014). Mapping Le Tour. Updated History and Route Map of Every Tour de France Race. Glasgow, UK: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-754399-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- de Visé, Daniel (2019). The Comeback: Greg LeMond, the True King of American Cycling, and a Legendary Tour de France. New York City: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-4718-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fife, Graeme (2000). Tour de France: The History, the Legend, the Riders. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84018-284-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fotheringham, William (2015). The Badger: Bernard Hinault and the Fall and Rise of French Cycling. London: Yellow Jersey Press. ISBN 978-0-22-409205-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heijmans, Jeroen; Mallon, Bill, eds. (2011). Historical Dictionary of Cycling. Lanham: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7175-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Laget, Françoise; Laget, Serge; Cazaban, Philippe; Montgermont, Gilles (2013). Tour de France: Official 100th Race Anniversary Edition. London: Quercus. ISBN 978-1-78206-414-5.

- Martin, Pierre (1985). Tour 85: The Stories of the 1985 Tour of Italy and Tour de France. With contributions from: Penazzo, Sergio; Baratino, Dante; Schamps, Daniel; Vos, Cor. Keighley, UK: Kennedy Brothers Publishing. OCLC 85076452.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McGann, Bill; McGann, Carol (2008). The Story of the Tour de France: 1965–2007. 2. Indianapolis, IN: Dog Ear Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59858-608-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moore, Richard (2008). In Search of Robert Millar. London: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-723502-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moore, Richard (2011). Slaying the Badger: LeMond, Hinault and the Greatest Ever Tour de France. London: Yellow Jersey Press. ISBN 978-0-22-409986-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moore, Richard (2014). Étape: The Untold Stories of the Tour de France's Defining Stages. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-750010-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nauright, John; Parrish, Charles (2012). Sports Around the World: History, Culture, and Practice. 2. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-300-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rendell, Matt (2008). Blazing Saddles: The Cruel and Unusual History of the Tour de France. London: Quercus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84724-382-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roche, Stephen; Cossins, Peter (2012). Born to Ride. London: Yellow Jersey Press. ISBN 978-0-22-409191-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ryan, Barry (2018). The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling's Golden Generation. Dublin: Gill Books. ISBN 978-07171-8153-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Martin, ed. (2009). The Telegraph Book of the Tour de France. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-84513-545-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- van den Akker, Pieter (2018). Tour de France Rules and Statistics: 1903–2018. Self-published. ISBN 978-1-79398-080-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Van Gucht, Ruben (2015). Hinault. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-47-291296-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wheatcroft, Geoffrey (2013). Le Tour: A History of the Tour de France. London: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4711-2894-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Woodland, Les, ed. (2007). The Yellow Jersey Companion to the Tour de France. London: Yellow Jersey Press. ISBN 978-0-22-408016-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Andrews, Guy (2016). Greg Lemond: Yellow Jersey Racer. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4729-4355-2.

External links

![]()