1948 Tour de France

The 1948 Tour de France was the 35th edition of the Tour de France, taking place from 30 June to 25 July. It consisted of 21 stages over 4,922 km (3,058 mi).

Route of the 1948 Tour de France followed counterclockwise, starting and finishing in Paris | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Race details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dates | 30 June – 25 July | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stages | 21 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Distance | 4,922 km (3,058 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Winning time | 145h 36' 56" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Results | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

The race was won by Italian cyclist Gino Bartali, who had also won the Tour de France in 1938. Bartali had almost given up during the race, but drew inspiration from a phone call from the Italian prime minister, who asked him to win the Tour de France to prevent civil unrest in Italy after assassination attempt against Togliatti. Bartali also won the mountains classification, while the team classification was won by the Belgian team.

Innovations and changes

The prize for wearing the yellow jersey was introduced in 1948,[1] sponsored by Les Laines, a French wool company.[2] In 1947, the media had complained that too many cyclists reached the end of the race, so the race was no longer heroic; this may have motivated a new rule between the third and the eighteenth stage, the rider last in the general classification was eliminated;[1][3] Where as the 1947 Tour de France had been France-centred, the 1948 race became a more cosmopolitan race.[4]

The Tour visited the Saar protectorate for the first time when the 18th stage passed Saarbrücken and Saarlouis. A second visit took place in 1953.[5]

The first live television broadcast from the Tour de France was in 1948,[6] when the arrival at the velodrome of Parc des Princes was broadcast live.[7]

Teams

.jpg)

As was the custom since the 1930 Tour de France, the 1948 Tour de France was contested by national and regional teams.

After there had not been an official Italian team allowed in the previous edition, the Italians were back. The Italian cyclists were divided between Gino Bartali and Fausto Coppi. Both argued in the preparation of the race about who would be the team leader. The Tour organisation wanted to have both cyclists in the race, so they allowed the Italians and Belgians to enter a second team.[8] In the end, Coppi refused to participate, and Bartali became the team leader.[9] The organisation still allowed the Italians and Belgians to enter a second team, but they were to be composed of young cyclists, and were named the Italy Cadets and the Belgium Aiglons.[8]

The Tour organisation invited the Swiss to send a team, as they wanted Ferdinand Kübler, the winner of the 1948 Tour de Suisse, in the race. Kübler refused this because he could earn more money in other races. When the brothers Georges and Roger Aeschlimann announced that they wanted to join the race, they were quickly accepted, especially because they were from Lausanne, where the Tour would pass through. They were put in a team with eight non-French cyclists living in France, and were named the Internationals.[10]

Twelve teams of ten cyclists entered the race, consisting of 60 French cyclists, 24 Italian, 22 Belgian, 6 Dutch, 4 Luxembourgian, 2 Swiss, 1 Polish and 1 Algerian cyclist.[11]

The teams entering the race were:[11]

- Belgium

- Netherlands/Luxembourg

- Internationals

- Italy

- France

- Belgium Aiglons

- Italy Cadets

- Centre/South-West

- Île-de-France/North-East

- West

- Paris

- South-East

Route and stages

Bartali's three stage wins in a row was the last time that happened, until Mario Cipollini achieved four in a row in 1999.[12] There were five rest days, in Biarritz, Toulouse, Cannes, Aix-les-Bains and Mulhouse.[7] The highest point of elevation in the race was 2,556 m (8,386 ft) at the summit tunnel of the Col du Galibier mountain pass on stage 14.[13][14]

| Stage | Date | Course | Distance | Type | Winner | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 June | Paris to Trouville | 237 km (147 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 2 | 1 July | Trouville to Dinard | 259 km (161 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 3 | 2 July | Dinard to Nantes | 251 km (156 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 4 | 3 July | Nantes to La Rochelle | 166 km (103 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 5 | 4 July | La Rochelle to Bordeaux | 262 km (163 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 6 | 5 July | Bordeaux to Biarritz | 244 km (152 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 6 July | Biarritz | Rest day | ||||

| 7 | 7 July | Biarritz to Lourdes | 219 km (136 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 8 | 8 July | Lourdes to Toulouse | 261 km (162 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 9 July | Toulouse | Rest day | ||||

| 9 | 10 July | Toulouse to Montpellier | 246 km (153 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 10 | 11 July | Montpellier to Marseille | 248 km (154 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 11 | 12 July | Marseille to Sanremo | 245 km (152 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 12 | 13 July | Sanremo to Cannes | 170 km (106 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 14 July | Cannes | Rest day | ||||

| 13 | 15 July | Cannes to Briançon | 274 km (170 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 14 | 16 July | Briançon to Aix-les-Bains | 263 km (163 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 17 July | Aix-les-Bains | Rest day | ||||

| 15 | 18 July | Aix-les-Bains to Lausanne | 256 km (159 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 16 | 19 July | Lausanne to Mulhouse | 243 km (151 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 20 July | Mulhouse | Rest day | ||||

| 17 | 21 July | Mulhouse to Strasbourg | 120 km (75 mi) | Individual time trial | ||

| 18 | 22 July | Strasbourg to Metz | 195 km (121 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 19 | 23 July | Metz to Liège (Belgium) | 249 km (155 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 20 | 24 July | Liège (Belgium) to Roubaix | 228 km (142 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 21 | 25 July | Roubaix to Paris | 286 km (178 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| Total | 4,922 km (3,058 mi)[17] | |||||

Race overview

As the Italian team had not entered the Tours de France of 1939 and 1947, it was the first Tour de France for Bartali since his victory ten years before in 1938. His results in the Giro d'Italia had not been well, and it was not thought that Bartali could compete for the win.[12]

Bartali however won the sprint in the first stage, and thanks to the bonification of one minute for the winner, he was leading the race. After that, the Italian team took a low profile in the race.[12] In the second stage, Bartali lost the lead already; although his teammate Vincenzo Rossello won the stage, Belgian Jan Engels took over the yellow jersey.[18]

In the third stage, a group escaped and built up a lead of almost 14 minutes. Among that group was Louison Bobet, and as he was the best-placed cyclist in that group he became the next leader. Also in that group was Roger Lambrecht; when Lambrecht again was able to be in the first group in the fourth stage, he took the lead, becoming the fourth rider in four stages to don the yellow jersey. Lambrecht kept it in the next stage, but after Bobet won the sixth stage, Bobet took back the lead, and the yellow jersey made him confident.[18] In the Pyrenées, Bartali won both stages in a sprint, but Bobet was near and became the hero of the French spectators.[18]

After the ninth stage, Bobet had built up a lead of more than nine minutes. In the tenth stage, he lost time, and Belgian cyclist Roger Lambrecht reduced the margin to 29 seconds. After the eleventh stage, Bobet was still in the lead, but was having problems, and after he fainted at the finish, he wanted to give up. After a meal, massage and sleeping, he changed his mind, and won the twelfth stage.[19]

After the twelfth stage, Bartali was 20 minutes behind. Bartali thought about quitting the tour, but was persuaded to race on.[20] That night, Bartali received a phone call while he was in bed. Alcide De Gasperi, prime minister of Italy, from the Christian Democratic party, told him that a few days earlier Palmiro Togliatti, leader of the Italian Communist Party, had been shot, and Italy might be on the edge of a civil war. De Gasperi asked Bartali to do his best to win a stage, because the sport news might distract people from the politics. Bartali replied that he would do better, and win the race.[12] The next day, Bartali won stage 13 with a large margin. In the general classification, he jumped to second place, trailing by only 66 seconds. In the fourteenth stage, Bartali and Bobet rode together over the Galibier and the Croix de Fer, but Bartali had been saving his energy, and left Bobet and every body else behind on the Col de Porte. Bartali won again, and took over the yellow jersey as leader of the general classification. Bobet was now in second place, eight minutes behind. The next stage, stage 15, was also won by Bartali. The sixteenth stage was not won by Bartali, but because his direct competitors lost time, he increased his lead to 32 minutes.[12] Bartali lost minutes in the time trial in stage 17, but his lead was never endangered.

With each stage win of Bartali (seven in total), the Italian excitement about the Tour de France increased, and the political tensions quieted.[21]

Classification leadership and minor prizes

The time that each cyclist required to finish each stage was recorded, and these times were added together for the general classification. If a cyclist had received a time bonus, it was subtracted from this total; all time penalties were added to this total. The cyclist with the least accumulated time was the race leader, identified by the yellow jersey.[22] The budget of the Tour de France in 1948 was 45 million Francs, from which one third was provided by private enterprises.[23] In total, 7 million Francs of prizes were awarded in the 1948 Tour de France. Of these, 600.000 Francs were given to Bartali for winning the general classification.[24] Bartali is the only cyclist to win two Tours de France ten years apart.[25] Of the 120 cyclists, 44 finished the race.

Points for the mountains classification were earned by reaching the mountain tops first.[26] There were two types of mountain tops: the hardest ones, in category A, gave 10 points to the first cyclist, the easier ones, in category B, gave 5 points to the first cyclist.

The team classification was calculated by adding the times in the general classification of the best three cyclists per team.[27]

The Souvenir Henri Desgrange was given in honour of Tour founder Henri Desgrange in the opening few kilometres of stage 1 at the summit of the Côte de Picardie in Versailles, Paris.[28][29][30] This prize was won by Roger Lambrecht.[29] The Tour de France in 1948 for the first time had a special award for the best regional rider.[19] This was won by third-placed Guy Lapébie.[7]

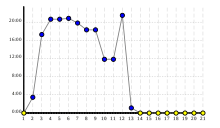

| Stage | Winner | General classification |

Mountains classification[lower-alpha 1] | Team classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gino Bartali | Gino Bartali | no award | Belgium |

| 2 | Vincenzo Rossello | Jan Engels | Belgium B | |

| 3 | Guy Lapébie | Louison Bobet | France | |

| 4 | Jacques Pras | Roger Lambrecht | Internationals | |

| 5 | Raoul Remy | |||

| 6 | Louison Bobet | Louison Bobet | ||

| 7 | Gino Bartali | Bernard Gauthier | France | |

| 8 | Gino Bartali | Jean Robic | ||

| 9 | Raymond Impanis | |||

| 10 | Raymond Impanis | Internationals | ||

| 11 | Gino Sciardis | |||

| 12 | Louison Bobet | France | ||

| 13 | Gino Bartali | |||

| 14 | Gino Bartali | Gino Bartali | Gino Bartali | |

| 15 | Gino Bartali | |||

| 16 | Edward Van Dijck | |||

| 17 | Roger Lambrecht | Belgium | ||

| 18 | Giovanni Corrieri | |||

| 19 | Gino Bartali | |||

| 20 | Bernard Gauthier | |||

| 21 | Giovanni Corrieri | |||

| Final | Gino Bartali | Gino Bartali | Belgium | |

Final standings

General classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Italy | 147h 10' 36" | |

| 2 | Belgium | + 26' 16" | |

| 3 | Centre/South-West | + 28' 48" | |

| 4 | France | + 32' 59" | |

| 5 | Netherlands/Luxembourg | + 37' 53" | |

| 6 | France | + 40' 17" | |

| 7 | Internationals | + 49' 56" | |

| 8 | Internationals | + 51' 36" | |

| 9 | Paris | + 55' 23" | |

| 10 | Belgium | + 1h 00' 03" | |

| Final general classification (11–44)[33] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Rider | Team | Time |

| 11 | Belgium | + 1h 00' 13" | |

| 12 | Paris | + 1h 02' 30" | |

| 13 | Paris | + 1h 25' 08" | |

| 14 | Belgium | + 1h 32' 13" | |

| 15 | Centre/South-West | + 1h 39' 49" | |

| 16 | France | + 1h 41' 26" | |

| 17 | France | + 1h 42' 48" | |

| 18 | Internationals | + 1h 45' 30" | |

| 19 | Italy | + 1h 48' 50" | |

| 20 | Belgium Aiglons | + 1h 59' 47" | |

| 21 | France | + 2h 01' 58" | |

| 22 | Belgium Aiglons | + 2h 15' 41" | |

| 23 | South-East | + 2h 15' 59" | |

| 24 | South-East | + 2h 34' 19" | |

| 25 | France | + 2h 38' 01" | |

| 26 | Centre/South-West | + 2h 42' 46" | |

| 27 | Italy | + 2h 46' 48" | |

| 28 | Paris | + 2h 56' 31" | |

| 29 | Italy | + 2h 59' 10" | |

| 30 | Belgium | + 3h 00' 54" | |

| 31 | Italy Cadets | + 3h 02' 55" | |

| 32 | Île-de-France/North-East | + 3h 05' 28" | |

| 33 | Italy | + 3h 05' 56" | |

| 34 | Italy | + 3h 07' 03" | |

| 35 | Île-de-France/North-East | + 3h 18' 44" | |

| 36 | Netherlands/Luxembourg | + 3h 24' 59" | |

| 37 | Internationals | + 3h 26' 21" | |

| 38 | Italy Cadets | + 3h 34' 29" | |

| 39 | South-East | + 3h 45' 13" | |

| 40 | Île-de-France/North-East | + 3h 48' 13" | |

| 41 | Italy | + 3h 48' 30" | |

| 42 | Netherlands/Luxembourg | + 3h 50' 41" | |

| 43 | South-East | + 4h 14' 57" | |

| 44 | Italy Cadets | + 4h 26' 43" | |

Mountains classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Italy | 62 | |

| 2 | France | 43 | |

| 3 | France | 38 | |

| 4 | Belgium | 30 | |

| 5 | France | 28 |

Team classification

| Rank | Team | Time |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Belgium | 443h 58' 20" |

| 2 | France | + 28' 16" |

| 3 | Paris | + 56' 29" |

| 4 | Internationals | + 1h 00' 30" |

| 5 | Italy | + 2h 11' 36" |

Aftermath

The 1948 Tour de France first showed the strengths of Louison Bobet. Bobet would be the first rider to win three consecutive Tours de France, from 1953 to 1955.[36] After the race, the Italian team manager Alfredo Binda said about Bobet: "If I would have directed Bobet, he would have won the Tour."[7]

Coppi, who had not competed in the 1948 Tour de France because of his bad relationship with Bartali, would enter and win the 1949 Tour de France.

Notes

- No jersey was awarded to the leader of the mountains classification until a white jersey with red polka dots was introduced in 1975.[32]

References

- "35ème Tour de France 1948" [35th Tour de France 1948]. Mémoire du cyclisme (in French). Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- Thompson 2006, p. 49.

- Thompson 2006, p. 115.

- Dauncey & Hare 2003, p. 213.

- Rainer Freyer (2013). "Die Tour de France im Saarland" (in German). Saar-Nostalgie. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- Dauncey & Hare 2003, p. 132.

- Augendre 2016, p. 39.

- Maso 2003, p. 37.

- Ligget, Raia & Lewis 2005, p. 213.

- Maso 2003, p. 26.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1948 – The starters". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Tom James (15 August 2003). "1948: Bartali saves Italy". Veloarchive. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- Augendre 2016, pp. 177–178.

- "Il 35º Giro di Francia si Metterà in moto domani" [The 35th Tour of France will start tomorrow]. Corriere dello Sport (in Italian). 29 June 1948. p. 1. Archived from the original on 21 February 2020.

- Arian Zwegers. "Tour de France GC top ten". CVCC. Archived from the original on 10 June 2009. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1948 – The stage winners". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Augendre 2016, p. 109.

- Amels 1984, p. 56.

- Amaury Sport Organisation. "The Tour - Year 1948". letour.fr. Archived from the original on 25 February 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- Bill Henderson (5 July 1996). "Looking back: Tour de France 1948". away.com. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- Barry Boyce (2004). "Gino "the Pious," an Inspirational Win". Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, pp. 452–453.

- Dauncey, p.110

- Amaury Sport Organisation. "l'Historique du Tour de France, Année 1948". letour.fr. Archived from the original on 15 July 2009. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- McGann & McGann 2006, pp. 156–159.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, p. 454.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, p. 455.

- "35ème Tour de France 1948 - 1ère étape" [35th Tour de France 1948 - 1st stage]. Mémoire du cyclisme (in French). Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- "Tour de France begonnen" [Tour de France begins]. Het Parool (in Dutch). 30 June 1948. p. 3 – via Delpher.

- "Versailles: les statues de La Fayette et Pershing inaugurées" [Versailles: La Fayette and Pershing statues inaugurated]. Le Parisien (in French). 5 October 2017. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- van den Akker, Pieter. "Informatie over de Tour de France van 1948" [Information about the Tour de France from 1948]. TourDeFranceStatistieken.nl (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- Cunningham, Josh (4 July 2016). "History of the Tour de France jerseys". Cyclist. Dennis Publishing. Archived from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1948 – Stage 21 Roubaix > Paris". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Tour-Giro-Vuelta". www.tour-giro-vuelta.net. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

- Maso, p. 303

- "Wall of Fame - Louison Bobet". Infostradasports. 2009. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

Bibliography

- Amels, Wim (1984). De Geschiedenis van de Tour de France 1903-1984 (in Dutch). Sport-Express. p. 56. ISBN 90-70763-05-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Augendre, Jacques (2016). Guide historique [Historical guide] (PDF). Tour de France (in French). Paris: Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dauncey, Hugh; Hare, Geoff (2003). The Tour de France, 1903-2003: A century of sporting structures, meanings, and values. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-5362-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ligget, Phil; Raia, James; Lewis, Sammarye (2005). Tour de France for dummies. For Dummies. p. 175. ISBN 0-7645-8449-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Maso, Benjo (2003). Wij waren allemaal goden (in Dutch). AmstelSport. ISBN 978-90-482-0003-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McGann, Bill; McGann, Carol (2006). The Story of the Tour de France: 1903–1964. 1. Indianapolis, IN: Dog Ear Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59858-180-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nauright, John; Parrish, Charles (2012). Sports Around the World: History, Culture, and Practice. 2. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-300-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thompson, Christopher S. (2006). The Tour de France: A Cultural History. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24760-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

![]()