1965 Tour de France

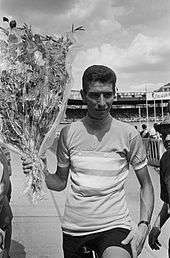

The 1965 Tour de France was the 52nd edition of the Tour de France, one of cycling's Grand Tours. It took place between 22 June and 14 July, with 22 stages covering a distance of 4,188 km (2,602 mi). In his first year as a professional, Felice Gimondi, a substitute replacement on the Salvarani team, captured the overall title ahead of Raymond Poulidor, last year's second-place finisher.

Route of the 1965 Tour de France | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Race details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dates | 22 June – 14 July | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stages | 22, including two split stages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Distance | 4,188 km (2,602 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Winning time | 116h 42' 06" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Results | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gimondi became one of only seven riders, the others being Alberto Contador, Vincenzo Nibali, Chris Froome and five-time Tour winners Jacques Anquetil, Eddy Merckx and Bernard Hinault to have won all three of the major Tours. Besides Gimondi's first tour and win, it was a first for other reasons: the 1965 Tour started in Cologne, Germany (the first time the Tour started in Germany,[1] and only the third time it started outside France), and it was the first time the start ramp was used in time trials.

Jan Janssen, who won the points classification the previous year successfully defended his title; he won another points title in 1967 and the overall title at the 1968 Tour de France.

Julio Jiménez won two stages and his first of three consecutive mountains classification. Jiminez also won the mountains classification at the 1965 Vuelta a España – becoming one of (now) four riders to complete the Tour/Vuelta double by winning both races' mountains competitions in the same year.

Teams

The 1965 Tour started with 130 cyclists, divided into 13 teams of 10 cyclists.[2] Each team had to include at least six cyclists with the same nationality.[3] The Molteni–Ignis team was a combined team, with 5 cyclists from Molteni and 5 from Ignis.[2]

The teams entering the race were:[2]

Pre-race favourites

Jacques Anquetil, who won the previous four Tours de France (1961–1964), did not participate in this tour. Cyclists in that time earned most of their income in criteriums, and Anquetil believed that even if he would win a sixth time, he would not get more money in those races.[4]

This made Raymond Poulidor, who became second in the previous Tour, the main favourite.[1]

Other favourites were Italians Vittorio Adorni and Gianni Motta. Adorni had won the Giro d'Italia earlier that year, helped by his team-mate Felice Gimondi who finished third in his first year as a professional. Originally, Gimondi was not planning to start the 1965 Tour, but was asked to do so after several team-mates were ill.[4]

Route and stages

The 1965 Tour de France started on 22 June, and had one rest day in Barcelona.[5] The highest point of elevation in the race was 2,360 m (7,740 ft) at the summit of the Col d'Izoard mountain pass on stage 16.[6][7]

| Stage | Date | Course | Distance | Type | Winner | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 22 June | Cologne (West Germany) to Liège (Belgium) | 149 km (93 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 1b | Liège (Belgium) | 22.5 km (14.0 mi) | Team time trial | Ford France–Gitane | ||

| 2 | 23 June | Liège (Belgium) to Roubaix | 200.5 km (124.6 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 3 | 24 June | Roubaix to Rouen | 240 km (150 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 4 | 25 June | Caen to Saint-Brieuc | 227 km (141 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 5a | 26 June | Saint-Brieuc to Châteaulin | 147 km (91 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 5b | Châteaulin | 26.7 km (16.6 mi) | Individual time trial | |||

| 6 | 27 June | Quimper to La Baule | 210.5 km (130.8 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 7 | 28 June | La Baule to La Rochelle | 219 km (136 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 8 | 29 June | La Rochelle to Bordeaux | 197.5 km (122.7 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 9 | 30 June | Dax to Bagnères-de-Bigorre | 226.5 km (140.7 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 10 | 1 July | Bagnères-de-Bigorre to Ax-les-Thermes | 222.5 km (138.3 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 11 | 2 July | Ax-les-Thermes to Barcelona (Spain) | 240.5 km (149.4 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 3 July | Barcelona | Rest day | ||||

| 12 | 4 July | Barcelona (Spain) to Perpignan | 219 km (136 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 13 | 5 July | Perpignan to Montpellier | 164 km (102 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 14 | 6 July | Montpellier to Mont Ventoux | 173 km (107 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 15 | 7 July | Carpentras to Gap | 167.5 km (104.1 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 16 | 8 July | Gap to Briançon | 177 km (110 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 17 | 9 July | Briançon to Aix-les-Bains | 193.5 km (120.2 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 18 | 10 July | Aix-les-Bains to Le Revard | 26.9 km (16.7 mi) | Mountain time trial | ||

| 19 | 11 July | Aix-les-Bains to Lyon | 165 km (103 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | ||

| 20 | 12 July | Lyon to Auxerre | 198.5 km (123.3 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 21 | 13 July | Auxerre to Versailles | 225.5 km (140.1 mi) | Plain stage | ||

| 22 | 14 July | Versailles to Paris | 37.8 km (23.5 mi) | Individual time trial | ||

| Total | 4,188 km (2,602 mi)[10] | |||||

Race overview

The race started in Germany, and the first stage, ending in Belgium, was won by Belgian Rik Van Looy. On the second stage, run over cobbles, three riders escaped: Bernard Vandekerkhove, Felice Gimondi and Victor Van Schil. Vandekerkhove won the stage, and became the new leader.[4]

On the third stage, there was again a group away, including Gimondi and André Darrigade. Darrigade was one of the best sprinters of that time, so Gimondi knew he would not win if it would end in a sprint. Gimondi therefore escaped with one kilometer to go. Gimondi was able to stay away, and won the stage; it was the first victory in his professional career.[4] Gimondi also took the lead in the general classification, represented by the yellow jersey; this made Gimondi a protected rider in his team because his sponsor wanted to keep the publicity associated with the yellow jersey as long as possible.[4]

The second part of the fifth stage was run as an individual time trial. It was won by Raymond Poulidor, but Gimondi was second, and kept his lead. He had a margin in the general classification of over two minutes on Vandekerkhove, while his team leader Adorni was in third place.[4]

In the seventh stage, Adorni fell. His team-mates, including Gimondi, waited for him and lost some time; because of this, Vandekerkhove took back the lead.[4]

The ninth stage was the first Pyrenean stage, and during that stage eleven riders abandoned because of sickness. This included the leader of the general classification Vandekerkhove, and also Adorni. Rumours about doping that went wrong circulated, but nothing was ever proven. Gimondi became the leader of the general classification again, and because his team leader Adorni had left the race, he also became the undisputed leader of this team.[4]

There were two more days in the Pyrenees, but these gave no big changes in the general classification. After stage eleven, Gimondi was still leading, with Poulidor in second place, more than three minutes behind. Poulidor expected that the inexperienced Gimondi would fail somewhere, and expected fourth-placed Motta to be his biggest rival. Poulidor announced he would attack on Mont Ventoux in stage fourteen.[4]

During that stage, Poulidor showed his strength, and won. He had a big margin over Motta, but Gimondi had stayed surprisingly close, and kept the lead in the general classification with 34 seconds.[4]

In the following Alp stages, Poulidor did not attack; he planned to take the lead in the mountain time trial of stage eighteen. But this was won by Gimondi, who thus increased his lead.[4]

The only realistic chance left for Poulidor to win back time was in the individual time trial that ended the race. Poulidor was a good time trialist, and on a good day he should have been able to win back enough time to win the race. But Gimondi was the fastest man that day, and won the stage, and thereby the Tour de France.[4]

Classification leadership and minor prizes

There were several classifications in the 1965 Tour de France, two of them awarding jerseys to their leaders.[11] The most important was the general classification, calculated by adding each cyclist's finishing times on each stage. The cyclist with the least accumulated time was the race leader, identified by the yellow jersey; the winner of this classification is considered the winner of the Tour.[12]

Additionally, there was a points classification. In the points classification, cyclists got points for finishing among the best in a stage finish, or in intermediate sprints. The cyclist with the most points lead the classification, and was identified with a green jersey.[13]

There was also a mountains classification. The organisation had categorised some climbs as either first, second, third, or fourth-category; points for this classification were won by the first cyclists that reached the top of these climbs first, with more points available for the higher-categorised climbs. The cyclist with the most points lead the classification, but was not identified with a jersey.[14]

For the team classification, the times of the best three cyclists per team on each stage were added; the leading team was the team with the lowest total time. The riders in the team that led this classification wore yellow caps.[15]

In addition, there was a combativity award given after each stage to the cyclist considered most combative. The split stages each had a combined winner. The decision was made by a jury composed of journalists who gave "stars". The cyclist with the most "stars" in all stages lead the "star classification".[16] Felice Gimondi won this classification.[5] The jury gave Cees Haast the prize more most unlucky cyclist, because he lost his sixth place in the general classification after a fall, and the prize for most sympathetic cyclist to Gianni Motta, because he was always in a good mood and did not look for apologies after losing to Gimondi.[17] The Souvenir Henri Desgrange was given in honour of Tour founder Henri Desgrange to the first rider to pass the summit of the Col du Lautaret on stage 17. This prize was won by Francisco Gabica.[18]

Final standings

General classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Salvarani | 116h 42' 06" | |

| 2 | Mercier–BP–Hutchinson | + 2' 40" | |

| 3 | Molteni–Ignis | + 9' 18" | |

| 4 | Pelforth–Sauvage–Lejeune | + 12' 43" | |

| 5 | Ford France–Gitane | + 12' 56" | |

| 6 | Ferrys | + 13' 15" | |

| 7 | Molteni–Ignis | + 14' 48" | |

| 8 | Flandria–Romeo | + 17' 36" | |

| 9 | Pelforth–Sauvage–Lejeune | + 17' 52" | |

| 10 | Kas–Kaskol | + 19' 11" |

| Final general classification (11–81)[21] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Rider | Team | Time |

| 11 | Wiel's–Groene Leeuw | + 19' 21" | |

| 12 | Peugeot–BP–Michelin | + 20' 32" | |

| 13 | Kas–Kaskol | + 24' 34" | |

| 14 | Peugeot–BP–Michelin | + 25' 07" | |

| 15 | Molteni–Ignis | + 25' 31" | |

| 16 | Wiel's–Groene Leeuw | + 28' 04" | |

| 17 | Peugeot–BP–Michelin | + 29' 35" | |

| 18 | Pelforth–Sauvage–Lejeune | + 29' 53" | |

| 19 | Salvarani | + 32' 48" | |

| 20 | Ford France–Gitane | + 34' 51" | |

| 21 | Flandria–Romeo | + 34' 52" | |

| 22 | Peugeot–BP–Michelin | + 36' 36" | |

| 23 | Kas–Kaskol | + 36' 45" | |

| 24 | Wiel's–Groene Leeuw | + 40' 11" | |

| 25 | Ferrys | + 40' 38" | |

| 26 | Kas–Kaskol | + 42' 00" | |

| 27 | Margnat–Paloma–Inuri–Dunlop | + 43' 23" | |

| 28 | Margnat–Paloma–Inuri–Dunlop | + 43' 34" | |

| 29 | Televizier | + 43' 45" | |

| 30 | Ferrys | + 47' 07" | |

| 31 | Solo–Superia | + 47' 29" | |

| 32 | Televizier | + 47' 30" | |

| 33 | Mercier–BP–Hutchinson | + 47' 49" | |

| 34 | Kas–Kaskol | + 46' 01" | |

| 35 | Solo–Superia | + 49' 16" | |

| 36 | Molteni–Ignis | + 50' 05" | |

| 37 | Kas–Kaskol | + 50' 55" | |

| 38 | Margnat–Paloma–Inuri–Dunlop | + 52' 00" | |

| 39 | Flandria–Romeo | + 52' 54" | |

| 40 | Mercier–BP–Hutchinson | + 53' 10" | |

| 41 | Mercier–BP–Hutchinson | + 53' 44" | |

| 42 | Pelforth–Sauvage–Lejeune | + 54' 12" | |

| 43 | Pelforth–Sauvage–Lejeune | + 54' 29" | |

| 44 | Ferrys | + 54' 49" | |

| 45 | Wiel's–Groene Leeuw | + 56' 11" | |

| 46 | Kas–Kaskol | + 57' 09" | |

| 47 | Wiel's–Groene Leeuw | + 57' 52" | |

| 48 | Wiel's–Groene Leeuw | + 58' 08" | |

| 49 | Molteni–Ignis | + 59' 12" | |

| 50 | Televizier | + 1h 02' 02" | |

| 51 | Televizier | + 1h 03' 42" | |

| 52 | Pelforth–Sauvage–Lejeune | + 1h 04' 17" | |

| 53 | Kas–Kaskol | + 1h 04' 19" | |

| 54 | Flandria–Romeo | + 1h 05' 14" | |

| 55 | Televizier | + 1h 05' 55" | |

| 56 | Solo–Superia | + 1h 08' 36" | |

| 57 | Televizier | + 1h 12' 51" | |

| 58 | Salvarani | + 1h 12' 53" | |

| 59 | Flandria–Romeo | + 1h 12' 58" | |

| 60 | Solo–Superia | + 1h 13' 45" | |

| 61 | Mercier–BP–Hutchinson | + 1h 15' 10" | |

| 62 | Margnat–Paloma–Inuri–Dunlop | + 1h 16' 04" | |

| 63 | Molteni–Ignis | + 1h 17' 54" | |

| 64 | Mercier–BP–Hutchinson | + 1h 20' 18" | |

| 65 | Ferrys | + 1h 20' 51" | |

| 66 | Ford France–Gitane | + 1h 22' 08" | |

| 67 | Ford France–Gitane | + 1h 22' 22" | |

| 68 | Salvarani | + 1h 23' 33" | |

| 69 | Wiel's–Groene Leeuw | + 1h 24' 45" | |

| 70 | Salvarani | + 1h 25' 45" | |

| 71 | Mercier–BP–Hutchinson | + 1h 27' 06" | |

| 72 | Solo–Superia | + 1h 27' 49" | |

| 73 | Molteni–Ignis | + 1h 28' 05" | |

| 74 | Molteni–Ignis | + 1h 28' 11" | |

| 75 | Mercier–BP–Hutchinson | + 1h 31' 07" | |

| 76 | Ferrys | + 1h 31' 39" | |

| 77 | Televizier | + 1h 37' 16" | |

| 78 | Molteni–Ignis | + 1h 37' 26" | |

| 79 | Salvarani | + 1h 40' 43" | |

| 80 | Flandria–Romeo | + 1h 41' 28" | |

| 81 | Flandria–Romeo | + 1h 41' 42" | |

| 82 | Pelforth–Sauvage–Lejeune | + 1h 43' 26" | |

| 83 | Ford France–Gitane | + 1h 43' 26" | |

| 84 | Solo–Superia | + 1h 43' 51" | |

| 85 | Ferrys | + 1h 45' 30" | |

| 86 | Salvarani | + 1h 46' 32" | |

| 87 | Ford France–Gitane | + 1h 46' 36" | |

| 88 | Margnat–Paloma–Inuri–Dunlop | + 1h 48' 48" | |

| 89 | Molteni–Ignis | + 1h 49' 12" | |

| 90 | Televizier | + 1h 49' 28" | |

| 91 | Salvarani | + 1h 53' 34" | |

| 92 | Pelforth–Sauvage–Lejeune | + 2h 03' 47" | |

| 93 | Margnat–Paloma–Inuri–Dunlop | + 2h 14' 18" | |

| 94 | Margnat–Paloma–Inuri–Dunlop | + 2h 22' 38" | |

| 95 | Ferrys | + 2h 23' 37" | |

| 96 | Pelforth–Sauvage–Lejeune | + 2h 37' 38" | |

Points classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pelforth–Sauvage–Lejeune | 144 | |

| 2 | Flandria–Romeo | 130 | |

| 3 | Salvarani | 124 | |

| 4 | Solo–Superia | 109 | |

| 5 | Wiel's–Groene Leeuw | 98 | |

| 6 | Flandria–Romeo | 94 | |

| 7 | Wiel's–Groene Leeuw | 85 | |

| 8 | Flandria–Romeo | 84 | |

| 8 | Kas–Kaskol | 84 | |

| 8 | Molteni–Ignis | 84 |

Mountains classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kas–Kaskol | 133 | |

| 2 | Flandria–Romeo | 74 | |

| 3 | Kas–Kaskol | 68 | |

| 4 | Salvarani | 55 | |

| 5 | Mercier–BP–Hutchinson | 48 | |

| 6 | Pelforth–Sauvage–Lejeune | 47 | |

| 7 | Molteni–Ignis | 45 | |

| 8 | Ferrys | 43 | |

| 9 | Solo–Superia | 30 | |

| 10 | Kas–Kaskol | 25 |

Team classification

| Rank | Team | Time |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kas–Kaskol | 349h 29' 19" |

| 2 | Pelforth–Sauvage–Lejeune | + 16' 08" |

| 3 | Molteni–Ignis | + 16' 35" |

| 4 | Peugeot–BP–Michelin | + 21' 36" |

| 5 | Wiel's–Groene Leeuw | + 36' 03" |

| 6 | Salvarani | + 38' 17" |

| 7 | Ferrys | + 46' 51" |

| 8 | Mercier–BP–Hutchinson | + 50' 21" |

| 9 | Televizier | + 54' 51" |

| 10 | Ford France–Gitane | + 1h 03' 52" |

| 11 | Flandria–Romeo | + 1h 10' 43" |

| 12 | Solo–Superia | + 1h 17' 08" |

| 13 | Margnat–Paloma–Inuri–Dunlop | + 1h 31' 09" |

Combativity classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Salvarani | 80 | |

| 2 | Pelforth–Sauvage–Lejeune | 58 | |

| 3 | Flandria–Romeo | 56 |

Notes

- No jersey was awarded to the leader of the mountains classification until a white jersey with red polka dots was introduced in 1975.[14]

References

- "52ème Tour de France 1965" [52nd Tour de France 1965]. Mémoire du cyclisme (in French). Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1965 – The starters". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "130 renners in de Tour de France". De waarheid (in Dutch). Delpher. 8 June 1965. p. 5. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- McGann & McGann 2008, pp. 6–13.

- Augendre 2016, p. 56.

- Augendre 2016, p. 178.

- "Tour de France". Het Vrije Volk (in Dutch). 21 June 1965. p. 9 – via Delpher.

- Zwegers, Arian. "Tour de France GC top ten". CVCC. Archived from the original on 10 June 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1965 – The stage winners". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Augendre 2016, p. 109.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, pp. 452–455.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, pp. 452–453.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, pp. 453–454.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, p. 454.

- Nauright & Parrish 2012, p. 455.

- van den Akker 2018, pp. 211–216.

- "Ongelukkigste: Duez en super-ongelukkigste: Kees Haast". Gazet Van Antwerpen (in Dutch). Concentra. 15 July 1965. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- "Jimenez le roi des Alpes où R. Binggeli est très à l'aise" [Jimenez the King of the Alps where R. Binggeli is very comfortable] (PDF). Feuille d'Avis du Valais (in French). 10 July 1965. p. 3 – via RERO.

- "Zeven Belgische ritoverwinningen" [Seven Belgian stage victories]. Gazet van Antwerpen (in Dutch). 15 July 1965. p. 16. Archived from the original on 14 February 2019.

- van den Akker, Pieter. "Informatie over de Tour de France van 1965" [Information about the Tour de France from 1965]. TourDeFranceStatistieken.nl (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1965 – Stage 22 Versailles > Paris". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Groene Trui". Gazet Van Antwerpen (in Dutch). Concentra. 15 July 1965. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- "Clasificacion General Definitiva del Gran Premio de la Montana" (PDF). Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 14 July 1965. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2019.

- "Slechts één Belgische ploeg heeft een prijs!". Gazet Van Antwerpen (in Dutch). Concentra. 15 July 1965. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- Lonkhuyzen, Michiel van. "Tour-Giro-Vuelta". www.tour-giro-vuelta.net. Archived from the original on 15 July 2010. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

Bibliography

- Augendre, Jacques (2016). Guide historique [Historical guide] (PDF). Tour de France (in French). Paris: Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McGann, Bill; McGann, Carol (2008). The Story of the Tour de France: 1965–2007. 2. Indianapolis, IN: Dog Ear Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59858-608-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nauright, John; Parrish, Charles (2012). Sports Around the World: History, Culture, and Practice. 2. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-300-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- van den Akker, Pieter (2018). Tour de France Rules and Statistics: 1903–2018. Self-published. ISBN 978-1-79398-080-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

![]()