1931 Tour de France

The 1931 Tour de France was the 25th edition of the Tour de France, which took place from 30 June to 26 July. It consisted of 24 stages over 5,091 km (3,163 mi).

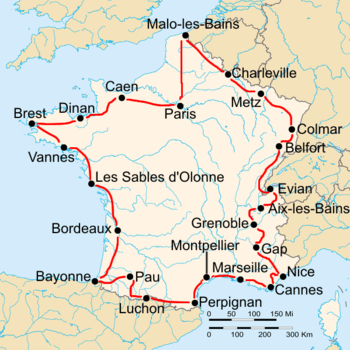

Route of the 1931 Tour de France followed counterclockwise, starting in Paris | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Race details | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dates | 30 June – 26 July | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Stages | 24 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Distance | 5,091 km (3,163 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Winning time | 177h 10' 03" | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Results | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

The race was won by French cyclist Antonin Magne. The sprinters Charles Pélissier and Rafaele di Paco both won five stages.[1]

The cyclists were separated into national teams and touriste-routiers, who were grouped into regional teams. In some stages (2, 3, 4, 6, 7 and 12), the national teams started 10 minutes before the touriste-routiers.[2]

One of these touriste-routiers was Max Bulla. In the second stage, when the touriste-routiers started 10 minutes later than the national teams, Bulla overtook the national teams, won the stage and took the lead, the only time in history that a touriste-routier was leading the Tour de France.[3]

Innovations and changes

In 1931, the touriste-routiers started 10 minutes later than the national teams in some stages (2, 3, 4, 6, and 12).[2] The number of rest days in the Tour de France was reduced to three.[1]

The time bonus for the winner, which had been used before in the 1924 Tour de France, was reintroduced.[2]

Teams

For the second year, the race was run in the national team format, with six different teams. Belgium, Italy, Germany and France each sent a team with eight cyclists. Australia and Switzerland sent a combined team, each with four cyclists. The last team was the Spanish team, with only one cyclist. In addition, 40 cyclists joined as touriste-routiers.[4]

The French team was favourite, because they had dominated the 1930 Tour. The most competition was expected from the Belgian team, followed by the Italian team.[3]

Race overview

In the early flat stages, the sprinters dominated.[1] In the second stage, Austrian Max Bulla won the stage. He was a touriste-routier, and had started ten minutes later than the A-class cyclists. He became the first, and only, touriste-routier to lead the Tour de France, and as of 2011 is the only Austrian to have led the race.[3][5] Max Bulla was the only Austrian cyclist to win a stage in the Tour de France until 2005, when Georg Totschnig won the 14th stage.[6]

After the fifth stage, Charles Pélissier and Rafaele di Paco shared the lead, thanks to the time bonus.[5] After the seventh stage, the race was still completely open: the first 30 cyclists in the general classification were within 10 minutes of each other.[7]

The defending champion, André Leducq, was not in good shape. His teammate Antonin Magne took over the leading role in the French team.[8] In the first mountain stage, Belgian Jef Demuysere was away, with Antonin Magne trying to get him back. After a while, Jef Demuysere flatted, and at that moment Magne passed him. Magne had not seen Demuysere, and still thought he was chasing him.[9] He kept racing as fast as he could, and finished four minutes ahead of Antonio Pesenti. In the next stage, a large group finished together, and Magne was still leading the race with Pesenti as his closest competitor.[3]

In the fourteenth stage, Pesenti was away with two teammates. The French team tried to get them back, but didn't succeed. In the end, Magne chased them by himself, but he could not get back to the Italians. His lead decreased to five minutes.[3] In the fifteenth stage, the Italians tried it again, but they were reeled back in by Charles Pélissier. Then Jef Demuysere got away, and won the stage with a margin of two minutes on Magne.[3]

Before the penultimate stage, Magne was still leading the race, closely followed by Pesenti. Magne was not sure if he would win the race, because that stage would be over cobbles, on which the Belgian cyclists were considered experts. The night before the stage, Magne could not sleep, and his roommate Leducq suggested that he could read some fan mail. Magne considered reading fan mail before the race was over as giving bad luck, but one oversized letter made him curious.[8] Magne opened it, and read a letter from a fan who claimed that Belgian cyclist Gaston Rebry (who had won the 1931 Paris–Roubaix race over the same cobbles) had written to his mother that he was planning to attack on the penultimate stage, together with Jef Demuysere. Leducq thought the letter was a joke, but Magne did not take the risk and told his teammates to stay close to Rebry and Demuysere.[3] After 60 km, Rebry and Demuysere took off, and Magne followed them. The Belgians took turns to attack Magne, but they could not get away from him.[3] They finished more than seventeen minutes ahead of Pesenti, which secured the victory for Magne and had Demuysere overtake Pesenti for the second place.[5]

Results

In stages 2, 3, 4, 6, 7 and 12, the national teams started 10 minutes before the touriste-routiers; in all other stages all cyclists started together. The cyclist to reach the finish in the least time was the winner of the stage. The time that each cyclist required to finish the stage was recorded. For the general classification, these times were added together. If a cyclist had received a time bonus, it was subtracted from this total; all time penalties were added to this total. The cyclist with the least accumulated time was the race leader, identified by the yellow jersey.

The team classification was calculated by adding up the times in the general classification of the three highest ranking cyclists per team; the team with the least time was the winner.

Stage winners

Five stages were won by touriste-routiers: Stages 2, 4, 7, 12 and 17, the highest number of stages ever won by touriste-routiers.[3]

| Stage | Date | Course | Distance | Type[lower-alpha 1] | Winner | Race leader | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 June | Paris to Caen | 208 km (129 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 2 | 1 July | Caen to Dinan | 212 km (132 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 3 | 2 July | Dinan to Brest | 206 km (128 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 4 | 3 July | Brest to Vannes | 211 km (131 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 5 | 4 July | Vannes to Les Sables d'Olonne | 202 km (126 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 6 | 5 July | Les Sables d'Olonne to Bordeaux | 338 km (210 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 7 | 6 July | Bordeaux to Bayonne | 180 km (110 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 8 | 7 July | Bayonne to Pau | 106 km (66 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 9 | 8 July | Pau to Luchon | 231 km (144 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | |||

| 10 | 10 July | Luchon to Perpignan | 322 km (200 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | |||

| 11 | 12 July | Perpignan to Montpellier | 164 km (102 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 12 | 13 July | Montpellier to Marseille | 207 km (129 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 13 | 14 July | Marseille to Cannes | 181 km (112 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 14 | 15 July | Cannes to Nice | 132 km (82 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | |||

| 15 | 17 July | Nice to Gap | 233 km (145 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | |||

| 16 | 18 July | Gap to Grenoble | 102 km (63 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | |||

| 17 | 19 July | Grenoble to Aix-les-Bains | 230 km (140 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | |||

| 18 | 20 July | Aix-les-Bains to Evian | 204 km (127 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | |||

| 19 | 21 July | Evian to Belfort | 282 km (175 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | |||

| 20 | 22 July | Belfort to Colmar | 209 km (130 mi) | Stage with mountain(s) | |||

| 21 | 23 July | Colmar to Metz | 192 km (119 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 22 | 24 July | Metz to Charleville | 159 km (99 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 23 | 25 July | Charleville to Malo-les-Bains | 271 km (168 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| 24 | 26 July | Malo-les-Bains to Paris | 313 km (194 mi) | Plain stage | |||

| Total | 5,091 km (3,163 mi)[13] | ||||||

General classification

| Rank | Rider | Team | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | France | 177h 10' 03" | |

| 2 | Belgium | + 12' 56" | |

| 3 | Italy | + 22' 51" | |

| 4 | Belgium | + 46' 40" | |

| 5 | Belgium | + 49' 46" | |

| 6 | Belgium | + 1h 10' 11" | |

| 7 | France | + 1h 18' 33" | |

| 8 | Germany | + 1h 20' 59" | |

| 9 | Australia/Switzerland | + 1h 29' 29" | |

| 10 | France | + 1h 30' 08" |

| Final general classification (11–35)[14] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Rider | Team | Time |

| 11 | Germany | + 1h 34' 03" | |

| 12 | Australia/Switzerland | + 1h 36' 43" | |

| 13 | France | + 1h 40' 38" | |

| 14 | France | + 1h 45' 11" | |

| 15 | Touriste-routier | + 1h 51' 32" | |

| 16 | Germany | + 2h 05' 58" | |

| 17 | Italy | + 2h 11' 11" | |

| 18 | Belgium | + 2h 15' 27" | |

| 19 | Germany | + 2h 16' 22" | |

| 20 | Germany | + 2h 23' 40" | |

| 21 | Australia/Switzerland | + 2h 25' 19" | |

| 22 | Germany | + 2h 28' 22" | |

| 23 | Germany | + 2h 36' 06" | |

| 24 | Touriste-routier | + 3h 05' 39" | |

| 25 | Italy | + 3h 09' 26" | |

| 26 | Touriste-routier | + 3h 33' 44" | |

| 27 | France | + 3h 41' 22" | |

| 28 | Touriste-routier | + 4h 06' 02" | |

| 29 | Touriste-routier | + 4h 20' 58" | |

| 30 | Italy | + 4h 39' 43" | |

| 31 | Touriste-routier | + 4h 42' 04" | |

| 32 | France | + 4h 43' 15" | |

| 33 | Touriste-routier | + 4h 47' 09" | |

| 34 | Touriste-routier | + 5h 13' 00" | |

| 35 | Australia/Switzerland | + 6h 27' 06" | |

Team classification

| Rank | Team | Time |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Belgium | 533h 19' 31" |

| 2 | France | + 57' 19" |

| 3 | Germany | + 3h 11' 38" |

| 4 | Austria/Switzerland | + 3h 53' 54" |

| 5 | Italy | + 4h 00' 06" |

Other classifications

The organing newspaper, l'Auto named a meilleur grimpeur (best climber), an unofficial precursor to the modern King of the Mountains competition. This award was won by Jef Demuysere.[16]

Aftermath

After the Tour de France was over, the winner Antonin Magne was so tired that he had to rest for several weeks.[7]

Notes

- There was no distinction in the rules between plain stages and mountain stages; the icons shown here indicate which stages included mountains.

- After the 5th stage, Pélissier and di Paco had the same time in the general classification. There was no rule for this, so both received the yellow jersey.

References

- "The Tour - year 1931". Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 16 July 2009. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- "25ème Tour de France 1931" (in French). Mémoire du cyclisme. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- McGann & McGann 2006, pp. 100–103.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1931 – The starters". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Tom James (15 August 2003). "1931: Magne makes his mark". Archived from the original on 2 October 2009. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- "An interview with Georg Totschnig, July 16, 2005 - His greatest sporting moment". Cyclingnews. 16 July 2005. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- "1931: Antonin Magne rijdt zich in zijn eerste Tour helemaal leeg" (in Dutch). Tourdefrance.nl. 19 March 2003. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- Barry Boyce (2004). "Two Victories in a Row for Team France". Cycling revealed. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- McGann & McGann 2006.

- Augendre 2016, p. 29.

- Arian Zwegers. "Tour de France GC top ten". CVCC. Archived from the original on 4 May 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2009.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1931 – The stage winners". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Augendre 2016, p. 108.

- "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1931 – Stage 24 Malo > Paris". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "La challenge international par équipes". Le Figaro (in French). Gallica Bibliothèque Numérique. 27 July 1931. p. 7. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- Michiel van Lonkhuyzen. "Tour-giro-vuelta". Retrieved 29 September 2009.

Bibliography

- Augendre, Jacques (2016). Guide historique [Historical guide] (PDF). Tour de France (in French). Paris: Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McGann, Bill; McGann, Carol (2006). The Story of the Tour de France: 1903–1964. 1. Indianapolis, IN: Dog Ear Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59858-180-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

![]()