Álvaro Obregón

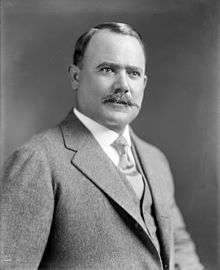

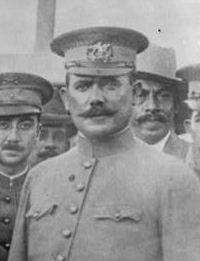

Álvaro Obregón Salido (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈalβaɾo oβɾeˈɣon]; February 19, 1880 – July 17, 1928) was a general in the Mexican Revolution, who became President of Mexico from 1920 to 1924. He supported Sonora's decision to follow Governor of Coahuila Venustiano Carranza as leader of a revolution against the Victoriano Huerta regime. Carranza appointed Obregón commander of the revolutionary forces in northwestern Mexico and in 1915 appointed him as his minister of war. In 1920, Obregón launched a revolt against Carranza, in which Carranza was assassinated. Obregón won the subsequent election with overwhelming support.

Álvaro Obregón | |

|---|---|

| |

| 39th President of Mexico | |

| In office December 1, 1920 – November 30, 1924 | |

| Preceded by | Adolfo de la Huerta |

| Succeeded by | Plutarco Elías Calles |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Álvaro Obregón Salido February 19, 1880 Siquisiva, Navojoa, Sonora |

| Died | July 17, 1928 (aged 48) San Ángel, Mexico City |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Political party | Laborist Party (PL) |

| Spouse(s) | María Tapia (1888-1971) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Rank | General |

| Battles/wars | Mexican Revolution |

Obregón's presidency was the first stable presidency since the Revolution began in 1910. He oversaw massive educational reform (with Mexican muralism flourishing), moderate land reform, and labor laws sponsored by the increasingly powerful Regional Confederation of Mexican Workers. In August 1923, he signed the Bucareli Treaty that clarified the rights of the Mexican government and U.S. oil interests and brought U.S. diplomatic recognition to his government.[1] In 1923–24, Obregón's finance minister, Adolfo de la Huerta, launched a rebellion, in part to protest the Bucareli Treaty; Obregón returned to the battlefield to crush the rebellion. In his victory, he was aided by the United States with arms and 17 U.S. planes that bombed de la Huerta's supporters.[2]

In 1924, Obregón's fellow Northern revolutionary general and hand-picked successor, Plutarco Elías Calles, was elected president. Although Obregón ostensibly retired to Sonora, he remained influential under Calles. Having pushed through constitutional reform to again make reelection possible, Obregón won the 1928 election. He was assassinated that year, before beginning his second term, by José de León Toral, a Mexican offended by the government's anti-religious laws. Toral's subsequent trial resulted in his conviction and execution by firing squad. A Capuchin nun named María Concepción Acevedo de la Llata, "Madre Conchita", was implicated in the case and was thought to be the mastermind behind Obregón's murder.[3]

Early years, 1880–1911

Obregón was born in Siquisiva, Sonora, Municipality of Navojoa, the son of Francisco Obregón and Cenobia Salido. Francisco Obregón had once owned a substantial estate, but his business partner supported Emperor Maximilian during the French intervention in Mexico (1861–1867), and the family's estate was confiscated by the Liberal government in 1867.[4] Francisco Obregón died in 1880, the year of Álvaro Obregón's birth. The boy was raised in poverty by his mother and his older sisters Cenobia, María, and Rosa.[5]

During his childhood, Obregón worked on the family farm and became acquainted with the Mayo people who also worked there. He attended a school run by his brother José in Huatabampo and received an elementary education. He spent his teenage years working a variety of jobs, before finding permanent employment in 1898 as a lathe operator at the sugar mill owned by his maternal uncles in Navolato, Sinaloa.[5]

In 1903, he married Refugio Urrea and in 1904, he left the sugar mill to sell shoes door-to-door, and then to become a tenant farmer. By 1906, he was in a position to buy his own small farm, where he grew chickpeas. The next year was tragic for Obregón as his wife and two of his children died, leaving him a widower with two small children, who were henceforth raised by his three older sisters. In 1909, Obregón invented a chickpea harvester and soon founded a company to manufacture these harvesters, complete with a modern assembly line. He successfully marketed these harvesters to chickpea farmers throughout the Mayo Valley.[5]

Military career, 1911–1915

Early military career, 1911–1913

Obregón entered politics in 1911 with his election as municipal president of the town of Huatabampo. Obregón expressed little sympathy for the Anti-reelectionist movement launched by Francisco I. Madero in 1908–1909 in opposition to President Porfirio Díaz. Thus, when Madero began the Mexican Revolution in November 1910 by issuing his Plan of San Luis Potosí, Obregón did not join the struggle against Porfirio Díaz.[6]

Madero succeeded in defeating Porfirio Díaz and thus became President of Mexico in November 1911.[6]

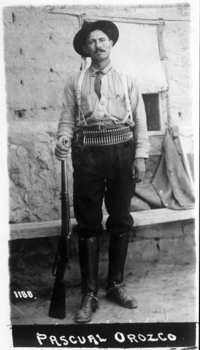

Obregón became a supporter of Madero shortly after Madero became President of Mexico. In March 1912, Pascual Orozco, a general who had fought with Madero during the Mexican Revolution, but had grown disaffected with Madero, launched a revolt against Madero's regime in Chihuahua with the financial backing of Luis Terrazas, a former Governor of Chihuahua and the largest landowner in Mexico.[6]

In April 1912, Obregón volunteered to join the local Maderista forces, the Fourth Irregular Battalion of Sonora, organized under the command of General Sanginés to oppose Orozco's revolt.[7]

This Battalion supported federal troops under the command of Victoriano Huerta sent by Madero to crush Orozco's rebellion. Within weeks of joining the Battalion, Obregón displayed signs of military genius. Obregón disobeyed his superior's orders but won several battles by luring his enemy into traps, surprise assaults, and encircling maneuvers.[7]

Obregón was quickly promoted through the ranks and attained the rank of Colonel before resigning in December 1912, following the victory over Orozco (with Orozco fleeing to the United States).[8]

Obregón had intended to return to civilian life in December 1912, but then in February 1913, the Madero regime was overthrown in a coup d'état (known to Mexican history as La decena trágica) orchestrated by Victoriano Huerta, Félix Díaz, Bernardo Reyes, and Henry Lane Wilson, the United States Ambassador to Mexico. Huerta assumed the presidency.[8]

Obregón immediately traveled to Hermosillo to offer his services to the government of Sonora in opposition to the Huerta regime. The Sonoran government refused to recognize the Huerta regime, and in early March 1913, Obregón was appointed chief of Sonora's War Department. In this capacity, he set out on a campaign, and in a matter of days had managed to drive federal troops out of Nogales, Cananea, and Naco. He soon followed up by capturing the port city of Guaymas. He squared off against federal troops in May 1913 at the battle of Santa Rosa through an encirclement of enemy forces. As commander of Sonora's forces, Obregón won the respect of many revolutionaries who had fought under Madero in 1910–11, most notably Benjamín G. Hill.[8]

Struggle against the Huerta Regime, 1913–1914

The Sonoran government was in contact with the government of Coahuila, which had also refused to recognize the Huerta regime and entered a state of rebellion. A Sonoran delegation headed by Adolfo de la Huerta traveled to Monclova to meet with the Governor of Coahuila, Venustiano Carranza. The Sonoran government signed on to Carranza's Plan of Guadalupe, by which Carranza became "primer jefe" of the newly proclaimed Constitutional Army. On 30 September 1913, Carranza appointed Obregón commander-in-chief of the Constitutional Army in the Northwest, with jurisdiction over Sonora, Sinaloa, Durango, Chihuahua, and Baja California.[8]

In November 1913, Obregón's forces captured Culiacán, thus securing the supremacy of the Constitutional Army in the entire area of Northwestern Mexico under Obregón's command.[8]

Obregón and other Sonorans were deeply suspicious of Carranza's Secretary of War, Felipe Ángeles, because they considered Ángeles to be a holdover of the old Díaz regime. At the urging of the Sonorans (the most powerful group in Carranza's coalition following Obregón's victories in the Northwest), Carranza downgraded Ángeles to the position of Sub-Secretary of War.[9]

In spite of his demotion, Ángeles formulated the rebel grand strategy of a three-prong attack south to Mexico City: (1) Obregón would advance south along the western railroad, (2) Pancho Villa would advance south along the central railroad, and (3) Pablo González Garza would advance south along the eastern railroad.[10]

Obregón began his march south in April 1914. Whereas Pancho Villa preferred wild cavalry charges, Obregón was again more cautious. Villa was soon at odds with Carranza, and in May 1914, Carranza instructed Obregón to increase the pace of his southern campaign to ensure that he beat Villa's troops to Mexico City. Obregón moved his troops from Topolobampo, Sinaloa, to blockade Mazatlán, and then to Tepic, where Obregón cut off the railroad from Guadalajara, Jalisco, to Colima, thus leaving both of these ports isolated.[11]

In early July, Obregón moved south to Orendaín, Jalisco, where his troops defeated federal troops, leaving 8000 dead, and making it clear that the Huerta regime was defeated. Obregón was promoted to major general. He continued his march south. Upon Obregón's arrival in Teoloyucan, Mexico State, it was clear that Huerta was defeated, and, on 11 August, on the mudguard of a car, Obregón signed the treaties that ended the Huerta regime. On 16 August 1914, Obregón and 18,000 of his troops marched triumphantly into Mexico City. He was joined shortly by Carranza, who marched triumphantly into Mexico City on 20 August.[11]

In Mexico City, Obregón moved to exact revenge on his perceived enemies. He believed that the Mexican Catholic Church had supported the Huerta regime, and he therefore imposed a fine of 500,000 pesos on the church, to be paid to the Revolutionary Council for Aid to the People.[12]

He also believed that the rich had been pro-Huerta, and he therefore imposed special taxes on capital, real estate, mortgages, water, pavement, sewers, carriages, automobiles, bicycles, etc.[13] Special measure were also taken against foreigners. Some of these were deliberately humiliating: for example, he forced foreign businessmen to sweep the streets of Mexico City.[14]

Break with Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata, 1914

Tensions between Carranza and Pancho Villa grew throughout 1914, as Villa created a number of diplomatic incidents that Carranza was worried would invite outside intervention in the Mexican Revolution. On 8 July 1914, Villistas and Carrancistas had signed the Treaty of Torreón, in which they agreed that after Huerta's forces were defeated, 150 generals of the Revolution would meet to determine the future shape of the country. However, Carranza disliked Villa's insubordination so much that he refused to let Villa march into Mexico City in August. In September, Villa and Carranza formally split, and during this time Obregón paid a visit to Villa that nearly resulted in Villa's having Obregón shot.[14]

The Convention that the Carrancistas and Villistas had agreed to in the Treaty of Torreón went ahead at Aguascalientes on 5 October 1914. Carranza did not participate in the Convention of Aguascalientes because he was not a general, but, as a general, Obregón participated. The Convention soon split into two major factions: (1) the Carrancistas, who insisted that the Convention should follow the promise of the Plan of Guadalupe and restore the 1857 Constitution of Mexico; and (2) the Villistas, who sought more wide-ranging social reforms than set out in the Plan of Guadalupe. The Villistas were supported by Emiliano Zapata, leader of the Liberation Army of the South, who had issued his own Plan of Ayala, which called for wide-ranging social reforms. For a month and a half, Obregón maintained neutrality between the two sides and tried to reach a middle ground that would avoid a civil war.[15]

Eventually, it became clear that the Villistas/Zapatistas had prevailed at the Convention; Carranza, however, refused to accept the Convention's preparations for a "pre-constitutional" regime, which Carranza believed was totally inadequate, and in late November, Carranza rejected the authority of the regime imposed by the Convention. Forced to choose sides, Obregón naturally sided with Carranza and left the Convention to fight for the Primer Jefe. He had made many friends amongst the Villistas and Zapatistas at the Convention and was able to convince some of them to depart with him. On December 12, 1914, Carranza issued his Additions to the Plan of Guadalupe, which laid out an ambitious reform program, including Laws of Reform, in conscious imitation of Benito Juárez's Laws of Reform.[15]

Battle with the Conventionists, 1915

Once again, Obregón was able to recruit loyal troops by promising them land in return for military service. In this case, in February 1915, the Constitutionalist Army signed an agreement with the Casa del Obrero Mundial ("House of the World Worker"), the labor union with anarcho-syndicalist connections which had been established during Francisco I. Madero's presidency. As a result of this agreement, six "Red Battalions" of workers were formed to fight alongside the Constitutionalists against the Conventionists Villa and Zapata. This agreement had the side effect of lending the Carrancistas legitimacy with the urban proletariat.[15]

Obregón's forces easily defeated Zapatista forces at Puebla in early 1915. However, the Villistas remained in control of large portions of the country. Forces under Pancho Villa were moving towards the Bajío; Felipe Ángeles' forces occupied Saltillo and thus dominated the northeast; the forces of Calixto Contreras and Rodolfo Fierro controlled western Mexico; and forces under Tomás Urbina were active in Tamaulipas and San Luis Potosí.[16]

The armies of Obregón and Villa clashed in four battles, collectively known as the Battle of Celaya, the largest military confrontation in Latin American history before the Falklands War of 1982. The first battle took place on 6 April and 7 April 1915 and ended with the withdrawal of the Villistas. The second, in Celaya, Guanajuato, took place between 13 April and 15 April, when Villa attacked the city of Celaya but was repulsed. The third was the prolonged position battle of Trinidad and Santa Ana del Conde between 29 April and 5 June, which was the definitive battle. Villa was again defeated by Obregón, who lost his right arm in the fight.[17]

Villa made a last attempt to stop Obregón's army in Aguascalientes on 10 July but without success. Obregón distinguished himself during the Battle of Celaya by being one of the first Mexicans to comprehend that the introduction of modern field artillery, and especially machine guns, had shifted the battlefield in favor of a defending force. In fact, while Obregón studied this shift and used it in his defense of Celaya, generals in the World War I trenches of Europe were still advocating bloody and mostly failing mass charges.[18]

Obregón's arm

During the battles with Villa, Obregón had his right arm blown off. The blast nearly killed him, and he attempted to put himself out of his misery and fired his pistol to accomplish that. The aide de camp who had cleaned his gun had neglected to put bullets in the weapon. In a wry story he told about himself, he joined in the search for his missing arm. "I was helping them myself, because it's not so easy to abandon such a necessary thing as an arm." The searchers had no luck. A comrade reached into his pocket and raised a gold coin. Obregón concluded the story, saying "And then everyone saw a miracle: the arm came forth from who knows where, and come skipping up to where the gold azteca [coin] was elevated; it reached up and grasped it in its fingers--lovingly--That was the only way to get my lost arm to appear."[19][20] The arm was subsequently embalmed and then put in the monument to Obregón on the site of where he was assassinated in 1928. Obregón always wore clothing tailored to show that he had lost his arm in battle, a visible sign of his sacrifice to Mexico.

Early political career, 1915–1920

Minister of War in Carranza's Preconstitutional Regime, 1915–1916

In May 1915, Carranza had proclaimed himself the head of what he termed a "Preconstitutional Regime" that would govern Mexico until a constitutional convention could be held. Carranza appointed Obregón as Minister of War in his new cabinet.[18]

As Minister of War, Obregón determined to modernize and professionalize the Mexican military thoroughly. In the process, he founded a staff college and a school of military medicine. He also founded the Department of Aviation and a school to train pilots. Munitions factories were placed under the direct control of the military.[18]

Break with Carranza, 1917–1920

In September 1916, Carranza convoked a Constitutional Convention, to be held in Querétaro, Querétaro. He declared that the liberal 1857 Constitution of Mexico would be respected, though purged of some of its shortcomings.

However, when the Constitutional Convention met in December 1916, it contained only 85 conservatives and centrists close to Carranza's brand of liberalism, a group known as the bloque renovador ("renewal faction"). Against them were 132 more radical delegates who insisted that land reform be embodied in the new constitution.

Obregón now broke with Carranza and threw his considerable weight behind the radicals. He met with radical legislators, as well as the intellectual leader of the radicals, Andrés Molina Enríquez, and came out in favor of all their key issues. In particular, unlike Carranza, Obregón supported the land reform mandated by Article 27 of the constitution. He also supported the heavily anticlerical Articles 3 and 130 that Carranza opposed.[18][21][22]

Shortly after swearing his allegiance to the new Constitution, Obregón resigned as Minister of War and retired to Huatabampo to resume his life as a chickpea farmer. He organized the region's chickpea farmers in a producer's league and briefly entertained the idea of going to France to fight on the side of the Allies in World War I. He made a considerable amount of money in these years, and also entertained many visitors. As the victorious general of the Mexican Revolution, Obregón remained enormously popular throughout the country.[23]

By early 1919, Obregón had determined to use his immense popularity to run in the presidential election that would be held in 1920. Carranza announced that he would not run for president in 1920, but refused to endorse Obregón, instead endorsing an obscure diplomat, Ignacio Bonillas. Obregón announced his candidacy in June 1919. In August, he concluded an agreement with Luis Napoleón Morones and the Regional Confederation of Mexican Workers, promising that if elected, he would create a Department of Labor, install a labor-friendly Minister of Industry and Commerce, and issue a new labor law.[24]

Obregón began to campaign in earnest in November 1919.[25]

In the meantime, Carranza seemed determined to stop Obregón. At Carranza's behest, the Senate stripped Obregón of his military rank, a move which only increased Obregón's popularity. Then, Carranza orchestrated a plot in which a minor officer claimed that Obregón was planning an armed uprising against the Carranza regime. Obregón was forced to disguise himself as a railwayman and flee to Guerrero, where one of his former subordinates, Fortunato Maycotte, was governor. When the election was held, Bonillas defeated Obregón.[26]

On 20 April 1920, Obregón issued a declaration in the town of Chilpancingo accusing Carranza of having used public money in support of Bonillas's presidential candidacy. He declared his allegiance to the Governor of Sonora, Adolfo de la Huerta, in revolution against the Carranza regime.[26]

On 23 April, the Sonorans issued the Plan of Agua Prieta, which triggered a military revolt against the president. Obregón's Sonoran forces were augmented by troops under General Benjamín G. Hill and the Zapatistas led by Gildardo Magaña and Genovevo de la O.

The revolt was successful and Carranza was deposed, after Obregon's forces captured Mexico City on 10 May 1920[27] On 20 May 1920, Carranza was killed in the state of Puebla in an ambush led by General Rodolfo Herrero as he fled from Mexico City to Veracruz on horseback.

For six months, from 1 June 1920 to 1 December 1920, Adolfo de la Huerta served as provisional president of Mexico until elections could be held.[28] When Obregón was declared the victor, de la Huerta stepped down and assumed the position of Secretary of the Treasury in the new government.

President of Mexico, 1920–1924

Obregón's election as president essentially signaled the end of the violence of the Mexican Revolution. The death of Lucio Blanco in 1922 and the assassination of Pancho Villa in 1923 would eliminate the last remaining obvious challenges to Obregón's regime. He pursued what seemed to be contradictory policies during his administration.[29]

Educational reforms and cultural developments

Obregón appointed José Vasconcelos (Rector of the National Autonomous University of Mexico who had been in exile 1915–1920 because of his opposition to Carranza) as his Secretary of Public Education.[30] Vasconcelos undertook a major effort to construct new schools across the country. Around 1,000 rural schools and 2,000 public libraries were built.[31]

Vasconcelos was also interested in promoting artistic developments that created a narrative of Mexico's history and the Mexican Revolution.[32] Obregón's time as president saw the beginning of the art movement of Mexican muralism, with artists such as Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, and Roberto Montenegro invited to create murals expressive of the spirit of the Mexican Revolution on the walls of public buildings throughout Mexico.[33]

Obregón also sought to shape public perceptions of the Revolution and its place in history by staging elaborate celebrations in 1921 on the centenary of Mexico's independence from Spain. There had been such celebrations in 1910 by the Díaz regime, commemorating the start of the insurgency by Miguel Hidalgo. The political fact of independence was achieved by former royalist officer Agustín de Iturbide, who was more celebrated by conservatives in post-independence Mexico than liberals. However, 1921 provided a date for Obregon's government to shape historical memory of independence and the Revolution.[34] After a decade of violence during the Revolution, the centennial celebrations provided an opportunity for Mexicans to reflect on their history and identity, as well as to enjoy diversions in peacetime. For Obregón, the centennial was a way to emphasize that revolutionary initiatives had historical roots and that like independence, the Revolution presented new opportunities for Mexicans.[35] Obregón "intended to use the occasion to shore-up popular support for the government, and, by extension, the revolution itself."[36] Unlike the centennial celebrations in 1910, the one of 1921 had no monumental architecture to inaugurate.[37]

Labor relations

Obregón kept his August 1919 agreement with Luis Napoleón Morones and the Regional Confederation of Mexican Workers (CROM) and created a Department of Labor, installed a labor-friendly Minister of Industry and Commerce, and issued a new labor law.[38]

Morones and CROM became increasingly powerful in the early 1920s and it would have been very difficult for Obregón to oppose their increased power. Morones was not afraid to use violence against his competitors, nearly eliminating the General Confederation of Workers in 1923.[38]

CROM's success did not necessarily translate to success for all of Mexico's workers, and Article 123 of the Constitution of Mexico was enforced only sporadically. Thus, while CROM's right to strike was recognized, non-CROM strikes were broken up by the police or the army. Also, few Mexican workers got Sundays off with pay, or were able to limit their workday to eight hours.[38]

Land reform

Land reform was far more extensive under Obregón than it had been under Carranza. Obregón enforced the constitutional land redistribution provisions, and in total, 921,627 hectares of land were distributed during his presidency.[38] However, Obregón was a successful commercial chickpea farmer in Sonora, and "did not believe in socialism or in land reform" and was in agreement with Madero and Carranza that "radical land reform might very well destroy the Mexican economy and lead to a return to subsistence agriculture."[39]

Relations with Catholic Church

Many leaders and members of the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico were highly critical of the 1917 constitution. They especially criticized Article 3, which forbade religious instruction in schools, and Article 130, which adopted an extreme form of separation of church and state by including a series of restrictions on priests and ministers of all religions to hold public office, canvass on behalf of political parties or candidates, or to inherit from persons other than close blood relatives.[38]

Although Obregón was suspicious of the Catholic Church, he was less anticlerical than his successor, Plutarco Elías Calles, would be. Calles's policies would lead to the Cristero War (1926–29). For example, Obregón sent Pope Pius XI congratulations upon his election in 1922 and, in a private message to the pope, emphasized the "complementarity" of the aims of the Catholic Church and the Mexican Revolution.[38]

In spite of Obregón's moderate approach, his presidency saw the beginnings of clashes between Catholics and supporters of the Mexican Revolution. Some bishops campaigned actively against land reform and the organization of workers into secular unions. Catholic Action movements were founded in Mexico in the wake of Pius XI's 1922 encyclical Ubi arcano Dei consilio, and supporters of the Young Mexican Catholic Action soon found themselves in violent conflict with CROM members.[40]

The most serious diplomatic incident occurred in 1923, when Ernesto Filippi, the Apostolic Nuncio to Mexico, conducted an open air religious service although it was illegal to hold a religious service outside a church. The government invoked Article 33 of the constitution and expelled Filippi from Mexico.[41]

Mexico-U.S. relations

As president, one of Obregón's top priorities was securing US diplomatic recognition of his regime, to resume normal Mexico–United States relations. Although he rejected the U.S. demand that Mexico rescind Article 27 of the constitution, Obregón negotiated a major agreement with the United States, the Bucareli Treaty of August 1923 that made some concessions to the US in order to gain diplomatic recognition.[42] It was particularly helpful when the Mexican Supreme Court, in a case brought by Texas Oil, declared that Article 27 did not apply retroactively. Another important arena in which Obregón resolved issues with the U.S. and other foreign governments was the Mexican-United States General Claims Commission.[43] Finance Minister Adolfo de la Huerta signed a deal in which Mexico recognized a debt of $1.451 million to international bankers. Finally, at the Bucareli Conference, Obregón agreed to an American demand that Mexico would not expropriate any foreign oil companies, and in exchange, the U.S. recognized his government. Many Mexicans criticized Obregón as a sellout (entreguista), including Adolfo de la Huerta for his actions at the Bucareli Conference.[41]

De la Huerta rebellion, 1923–24

In 1923, Obregón endorsed Plutarco Elías Calles for president in the 1924 election in which Obregón was not eligible to run. Finance Minister Adolfo de la Huerta, who had served as interim president in 1920 before he stepped aside in favor of Obregón, believed that he deserved to be the next president and that Obregón was repeating Carranza's mistake of imposing his own candidate on the country. De la Huerta accepted the nomination of the Cooperativist Party to be its candidate in the presidential elections.[44]

De la Huerta then organized an uprising against Obregón. Over half of the army joined De la Huerta's rebellion, with many of Obregón's former comrades in arms now turning on him. Rebel forces massed in Veracruz and Jalisco.[44]

In a decisive battle at Ocotlán, Jalisco, Obregón's forces crushed the rebel forces. Diplomatic recognition by the United States following the signing of the 1923 Bucareli Treaty was significant in Obregón's victory over rebels. The U.S. supplied Obregón arms but also sent 17 U.S. planes, which bombed rebels in Jalisco.[2] Obregón hunted down many of his former friends and had them executed.[45]

Following the crushing of the rebellion, Calles was elected president, and Obregón stepped down from office.

Later years, 1924–1928

Following the election of Calles as president, Obregón returned to Sonora to farm. He led an "agricultural revolution" in the Yaqui Valley, where he introduced modern irrigation. Obregón expanded his business interests to include a rice mill in Cajeme, a seafood packing plant, a soap factory, tomato fields, a car rental business, and a jute bag factory.[46]

Obregón remained in close contact with President Calles, whom he had installed as his successor, and was a frequent guest of Calles at Chapultepec Castle. This prompted fears that Obregón was intending to follow in the footsteps of Porfirio Díaz and that Calles was merely a puppet figure, the equivalent of Manuel González. These fears became acute in October 1926, when the Mexican Congress repealed term limits, thus clearing the way for Obregón to run for president in 1928.[46]

Obregón returned to the battlefield for the period October 1926 to April 1927 to put down a rebellion led by the Yaqui people. This was somewhat ironic because Obregón had first risen to military prominence commanding Yaqui troops, to whom he promised land, and the 1926–27 Yaqui rebellion was a demand for land reform. In all likelihood, Obregón participated in this campaign in order to prove his loyalty to the Calles government, to show his continued influence over the military, and also to protect his commercial interests in the Yaqui Valley, which had begun to suffer as a result of the increasing violence in the region.[47]

Obregón formally began his presidential campaign in May 1927. CROM and a large part of public opinion were against his re-election, but he still counted on the support of most of the army and of the National Agrarian Party.

Two of Obregón's oldest allies, General Arnulfo R. Gómez and General Francisco "Pancho" Serrano, opposed his re-election. Serrano launched an anti-Obregón rebellion and was ultimately assassinated. Gómez later called for an insurrection against Obregón, but was soon killed as well.[48]

Re-election and assassination

Obregón won the 1928 Mexican presidential election, but months before assuming the presidency he was assassinated. Calles's harsh treatment of Roman Catholics had led to a rebellion known as the Cristero War, which broke out in 1926. As an ally of Calles, Obregón was hated by Catholics and was assassinated in La Bombilla Café[49] on July 17, 1928, shortly after his return to Mexico City, by José de León Toral, a Roman Catholic opposed to the government's anti-Catholic policies.[50]

Honors

Álvaro Obregón was awarded Japan's Order of the Chrysanthemum at a special ceremony in Mexico City. On November 26, 1924, Baron Shigetsuma Furuya, Special Ambassador from Japan to Mexico, conferred the honor on the President.[51]

Legacy and posthumous recognition

Although Obregón was a gifted military strategist during the Revolution and decisively defeated Pancho Villa's División del Norte at the Battle of Celaya and went on to become President of Mexico, his posthumous name recognition and standing as a hero of the Revolution is nowhere near that of Villa's or Emiliano Zapata's. As president, he successfully gained recognition from the United States in 1923, settled for a period the dispute with the U.S. over oil via the Bucareli Treaty, gain full rein to his Secretary of Public Education, José Vasconcelos, who expanded access to learning for Mexicans by building schools, but also via public art of the Mexican muralists. Perhaps as with Porfirio Díaz, Obregón saw himself as indispensable to the nation and had the Constitution of 1917 amended so that he could run again for the presidency in Mexico. This bent and, in many people's minds, violated the revolutionary rule "no re-election" that had been enshrined in the constitution.

His assassination in 1928 before he could take the presidential office created a major political crisis in Mexico, which was solved by the creation of the National Revolutionary Party by his fellow Sonoran, General and former President Plutarco Elías Calles.

An imposing monument to Álvaro Obregón is located in the Parque de la Bombilla in the San Ángel neighborhood of southern Mexico City. It is Mexico's the largest monument to a single revolutionary and stands on the site where Obregón was assassinated.[52] The monument held Obregón severed, and over the years, increasingly deteriorating right arm that he lost in 1915. The monument now has a marble sculpture of the severed arm, after the arm itself was incinerated in 1989. Obregón's body is buried in Huatabampo, Sonora, rather than the Monument to the Revolution in downtown Mexico City where other revolutionaries are now entombed. In Sonora, Obregón is honored with an equestrian statue, where he is shown as a vigorous soldier with two arms.

In Sonora, the second largest city, Ciudad Obregón is named for the revolutionary leader. Obregón's son Álvaro Obregón Tapia served one term as the governor of Sonora as a candidate for the Institutional Revolutionary Party, founded following Obregón's assassination. The Álvaro Obregón Dam, built near Ciudad Obregón, became operational during the gubernatorial term of Obregón's son.

Obregón is honored in the name of a genus of small cactus indigenous to Mexico – Obregonia denegrii.[53]

In popular culture

In the novel The Friends of Pancho Villa (1996) by James Carlos Blake, Obregón is a major character.

Obregón is also featured in the novel Il collare spezzato by Italian writer Valerio Evangelisti (2006).

Obregón's legacy and lost limb are the subjects of Mexican-American singer-songwriter El Vez's "The Arm of Obregón", from his 1996 album G.I. Ay! Ay! Blues.[54]

See also

References

- Cline, Howard F. The United States and Mexico. Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1961, p. 208.

- Cline, U.S. and Mexico, p. 208.

- Heilman, Jaymie. "The Demon Inside: Madre Conchita, Gender, and the Assassination of Obregon". Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos, 18.1 (2002): 23–60.

- Krauze, Enrique (1997). Mexico: Biography of Power, p. 374, p. 374, at Google Books

- Krauze, p. 375, p. 375, at Google Books

- Krauze, p. 377, p. 377, at Google Books

- Krauze, p. 378.

- Krauze, p. 379.

- Slattery, Matthew (1982). Felipe Ángeles and the Mexican Revolution, pp. 59–60; Katz, Friedrich (1998). The Life and Times of Pancho Villa, p. 277, p. 277, at Google Books

- Slattery, p. 61.

- Krauze, p. 380, p. 380, at Google Books

- Krauze, p. 382, p. 382, at Google Books

- Krauze, pp. 382–383, p. 382, at Google Books

- Krauze, p. 383, p. 383, at Google Books

- Krauze, p. 384, p. 384, at Google Books

- Krauze, pp. 384–385, p. 384, at Google Books

- Krauze, pp. 386–387.

- Krauze, p. 387, p. 387, at Google Books

- quoted in Dulles, John W.F. Yesterday in Mexico: A Chronicle of Revolution, 1919-1936. Austin: University of Texas 1961, pp. 3–4.

- Buchenau, Jürgen. "The Arm and Body of the Revolution: Remembering Mexico's Last Caudillo, Álvaro Obregón" in Lyman L. Johnson, ed. Body Politics: Death, Dismemberment, and Memory in Latin America. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2004, pp. 179–207.

- Riner, D. L.; Sweeney, J. V. (1991). Mexico: meeting the challenge. Euromoney. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-870031-59-2.

- D'Antonio, William V.; Pike, Fredrick B. (1964). Religion, revolution, and reform: new forces for change in Latin America. Praeger. p. 66.

- Buchenau, pp. 94–97.

- Krauze, pp. 375–389, p. 375, at Google Books

- Krauze, p. 389, p. 389, at Google Books

- Krauze, p. 390, p. 390, at Google Books

- https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SPNP19200510.2.16&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN--------1

- Krauze, p. 392.

- Katz, Friedrich. The Life and Times of Pancho Villa, Stanford: Stanford University Press 1998, 730–32.

- Krauze, p. 393.

- Meyer, Michael C. and Sherman, William L. The Course of Mexican History.

- Mulvey, Laura; Wollen, Peter (1982). Frida Kahlo and Tina Modotti. London: Whitechapel Gallery. p. 12. ISBN 0854880550.

- Krauze, p. 394, p. 394, at Google Books

- Gonzales, Michael J. "Imagining Mexico in 1921: Visions of the Revolutionary State and Society in the Centennial Celebration in Mexico City", Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos vol. 25, (2) 2009, pp. 247–270.

- Gonzales, "Imagining Mexico in 1921", p. 249.

- Gonzales, "Imagining Mexico in 1921", p. 251.

- Gonzales, "Imagining Mexico in 1921", pp. 253–54.

- Krauze, p. 395, p. 395, at Google Books

- Katz, The Life and Times of Pancho Villa, p. 731.

- Krauze, pp. 395–396, p. 395, at Google Books

- Krauze, p. 396, p. 396, at Google Books

- Cline, U.S. and Mexico, pp. 207–208.

- Cline, U.S. and Mexico, pp. 208–210.

- Krauze, p. 397, p. 397, at Google Books

- Krauze, p. 398, p. 398, at Google Books

- Krauze, p. 399.

- Buchenau, pp. 150–51.

- Krauze, p. 401, p. 401, at Google Books

- "P&A Photos #173503" - New York Bureau

- Krauze, p. 403, p. 403, at Google Books

- "Japan Decorates Obregon; Order of the Chrysanthemum is Conferred by Special Ambassador", New York Times, 28 November 1924.

- "Monumento al General Álvaro Obregón, Mexico City", MyTravelGuide.com

- Eggli, Urs et al. (2004). Etymological Dictionary of Succulent Plant Names, pp. 169, 64, p. 169, at Google Books

- McLeod, Kembrew. "El Vez: G.I. Ay! Ay! Blues" at AllMusic. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

Further reading

- Buchenau, Jürgen (2004) "The Arm and Body of a Revolution: Remembering Mexico's Last Caudillo, Álvaro Obregón" in Lyman L. Johnson, ed. Body Politics: Death, Dismemberment, and Memory in Latin America. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, pp. 179–207.

- Buchenau, Jürgen (2011). The Last Caudillo: Alvaro Obregón and the Mexican Revolution. Chichester, England: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Castro, Pedro (2009). Álvaro Obregón: Fuego y cenizas de la Revolución Mexicana. Ediciones Era – Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes. ISBN 978-607-445-027-9 (ERA) – ISBN 978-607-455-257-7 (CNCA); Sitio de Pedro Castro

- Eggli, Urs and Newton, Leonard E. (2004). Etymological Dictionary of Succulent Plant Names. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-00489-9; OCLC 248883002

- Hall, Linda B. (1981). Álvaro Obregón: power and revolution in Mexico, 1911–1920. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9780890961131; OCLC 7202959

- Hall, Linda B. "Álvaro Obregón and the Politics of Mexican Land Reform, 1920-1924", Hispanic American Historical Review (1980) 60#2 pp. 213–238 in JSTOR.

- Heilman, Jaymie. "The Demon Inside: Madre Conchita, Gender, and the Assassination of Obregón". Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos, 18.1 (2002): 23-60.

- Katz, Friedrich (1998). The Life and Times of Pancho Villa. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3045-7; ISBN 978-0-8047-3046-4; OCLC 253993082

- Krauze, Enrique, Mexico: Biography of Power. New York: HarperCollins 1997. ISBN 0-06-016325-9

- Lomnitz-Adler, Claudio (2001). Deep Mexico, Silent Mexico: an Anthropology of Nationalism. University of Minnesota Press.

- Lucas, Jeffrey Kent (2010). The Rightward Drift of Mexico's Former Revolutionaries: The Case of Antonio Díaz Soto y Gama. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 9780773436657; F1234.D585 L83 2010

- Slattery, Matthew (1982). Felipe Ángeles and the Mexican Revolution. Parma Heights, Ohio: Greenbriar Books. ISBN 978-0-932970-34-3; OCLC 9108261

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alvaro Obregon. |

- Admiring essay on the Battle of Celaya with a focus on the tactics used by General Obregón.

- Newspaper clippings about Álvaro Obregón in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Adolfo de la Huerta |

President of Mexico 1 December 1920 – 30 November 1924 |

Succeeded by Plutarco Elías Calles |