Liberation Army of the South

The Liberation Army of the South (Spanish: Ejército Libertador del Sur, ELS) was a guerrilla force led for most of its existence by Emiliano Zapata that took part in the Mexican Revolution from 1911 to 1920. During that time, the Zapatistas fought against the national governments of Porfirio Díaz, Francisco Madero, Victoriano Huerta, and Venustiano Carranza. Their goal was rural land reform, specifically reclaiming communal lands stolen by hacendados in the period before the revolution. Although rarely active outside their base in Morelos, they allied with Pancho Villa to support the Conventionists against the Carrancistas. After Villa's defeat, the Zapatistas remained in open rebellion. It was only after Zapata's 1919 assassination and the overthrow of the Carranza government that Zapata's successor, Gildardo Magaña, negotiated peace with President Álvaro Obregón.

| Liberation Army of the South Zapatistas | |

|---|---|

Ejército Libertador del Sur Participant in the Mexican Revolution | |

| |

| Active | 1911–1920 |

| Ideology | Zapatismo Agrarianism |

| Political position | Left wing |

| Leaders |

|

| Headquarters | Variously Ayala or the mountains |

| Area of operations | Concentrated in the state of Morelos. Incursions into Puebla, Guerrero, and Mexico City. |

| Size | 25000 (1914)[1] |

| Part of | Conventionists (1914-1917) |

| Allies |

|

| Opponent(s) | Presidents of Mexico

Factions

|

| Battles and war(s) | Battle of Cuautla |

Origins

The Zapatistas were formed in the south-central state of Morelos. Morelos is small and densely populated, with an agricultural economy defined by the conflict between villages and large, sugar-producing haciendas.[2] The rights of the villages to their communal lands had been codified during the colonial era, but successive post-independence governments had allied with the hacendados to revoke those rights. Liberal land reforms privatized communally owned land, and the industrialization of agriculture during the Porfiriato intensified the demand for water and land.[2][3] Friendly courts awarded orchards, fields, and water sources to the haciendas. Between 1884 and 1905, eighteen towns in Morelos disappeared as lands were taken away.[4] Deprived of their means of subsistence, the population of Morelos was suffering from famine and general impoverishment by the turn of the century. Thousands had become wage laborers on the haciendas.[2] In 1909, Pablo Escandón y Barrón became governor in a rigged election, siding even more aggressively with the hacendados. In response, village leaders including Emiliano Zapata, Gabriel Tepepa, and Pablo Torres Burgos formed a local defense committee. They soon declared themselves in support of Francisco Madero, taking up arms in February of 1911.

History

Maderista revolution and interim presidency, Feb.–Nov. 1911

The defense committee originally aligned with Madero due to the promises of land reform in the Plan of San Luis Potosí,[3] with Torres Burgos being appointed commanding officer. However, there was essentially no coordination with Pascual Orozco's forces in the north. They saw great early success in recruiting from among the desperate population, amassing a force of around 5,000.[1] Governor Escandón fled the state with a portion of the federal forces, giving the rebels an opening to attack cities. In March, Torres Burgos was killed and Zapata was elected leader. He managed to avoid a trap laid by reactionary rebels under the Figueroa brothers and continue to gather strength. In May, Zapata scored a series of victories, first at Jojutla and then at Cuautla. The Battle of Cuautla was bloody and prolonged, pitting numerically superior rebels against a better-equipped and well-entrenched federal army. After suffering mass casualties from machine guns, the rebels had to take the city street by street. Nonetheless, Zapata's eventual victory put him dangerously close to the capital, and helped convince Porfirio Díaz to resign the presidency.[1] The rebel forces then occupied Cuernavaca, bringing most of Morelos under their control.

During the interim presidency of Francisco León de la Barra, Madero insisted Zapata disarm and disband his forces.[1][5] Madero's reluctance to take action on land reform made Zapata reluctant, but he had little choice but to comply. Tensions flared when the hacendado governor attempted to block Zapata from taking up his promised position as commander of the local police.[6] In July, news of a plot to assassinate Madero in the neighboring state of Puebla alarmed Zapata, and he rapidly re-mobilized to march to the politician's defense. Although the march was called off, Zapata and the other rebel commanders were now much more wary of laying down their arms. De la Berra ordered General Huerta to force Zapata to surrender unconditionally. Huerta quickly took over the state, and civil law was suspended in August.[6] Although Madero attempted negotiations to avoid violence, on August 23 Huerta and Ambrosia Figueroa (now allied with the regime) began military operations against the rebels. This made them feel that Madero had betrayed them, and set the stage for their break with him three months later. The small rebel force evaded destruction by first fleeing to Puebla, then reappearing in Morelos once Huerta had moved his army to follow them. The Morelos rebels swelled to around 1,500 and by late October lay claim to important territory near Mexico City.[6] This was a humiliation for Huerta, and he lost his post.

Break with Madero, Nov. 1911

After Madero's inauguration on November 6th, it appeared as if the rebellion in Morelos could end peacefully. Negotiations in Ayala seemed to be proceeding well when the federal army under Casso Lopez suddenly surrounded Zapata's forces. Madero issued an order for Zapata to surrender with the promise the compromise would be honored.[6] Zapata refused, as he received this order as the federal forces were already preparing to attack. His forces escaped into the Puebla mountains and there Zapata issued the Plan of Ayala, written by Otilio Montaño.[1] In this document, Zapata denounced Madero and outlined what would become the underpinnings of Zapatismo, a radical agrarianism based on seizing land from the haciendas and restoring it to the villages.

Revolution against Huerta, Feb. 1913–July 1914

Fighting continued against the successive leaders Victoriano Huerta and Venustiano Carranza.

Convention and civil war, 1914-1917

.jpg)

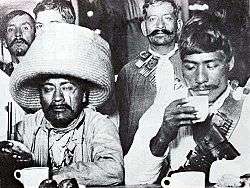

In 1914, Zapata met at the head of his army with Pancho Villa and his forces at Mexico City to determine the course of the revolution, but they returned to their respective territories without a connected anti-Constitutionalist coalition.[7] When back in Morelos, the Zapatistas fortified themselves against incursions by the forces eager to reassume control of the liberated territories known as the Morelos Commune.

Zapata's assassination and decline

Zapata's assassination in 1919 struck a mortal blow to Zapatistas, and the army slowly disbanded afterwards.

Structure

The Zapatistas were mainly poor peasants who wished to spend much of their time working their land to produce an income. As a result, Zapatista soldiers tended to serve for several months at a time, and then return home to spend most of the year farming.

The structure of the Zapatista army was very loose and the rank system limited in scope. The Zapatista army was united entirely by the charismatic leadership of Zapata. It was divided into small, largely independent units rarely numbering more than one hundred men, each commanded by a chief (jefe). These units spent the overwhelming majority of their time separated from the other units. Officer ranks were eventually introduced to coordinate groups. The chief of a unit over about fifty men was, generally speaking, given the rank of general. Smaller bands were commanded by colonels and captains. Not all captains were official; that is to say, recognised by Zapata and senior Zapatistas, some being unofficially proclaimed captains by their unit. Beyond Zapata's overall command and the leadership of bands, there was limited use of ranks or hierarchy. Sub-officer ranks were introduced late in the revolution in an effort to create a more disciplined force. One of Zapata's famous dictums was "al ratero perdono pero al traidor jamas"; "a robber I can forgive, but a traitor... never."

Legacy

After Obregón's ascension to the presidency, Magaña secured the passage of land reform aligned with the Plan of Ayala. During the 1990s, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation drew philosophical and tactical inspiration from the Liberation Army of the South, launching an insurgency that is ongoing in 2020.

See also

References

- Alba, Victor. "Emiliano Zapata". Encyclopedia Brittanica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- "Morelos: The Land of Zapata". Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- Brunk, Samuel (Apr 1996). "'The Sad Situation of Civilians and Soldiers': The Banditry of Zapatismo in the Mexican Revolution". The American Historical Review. 101 (2): 331–353.

- Morelos: Monografía estatal: 1982. Secretaria de Educación Publica. p. 152–158.

- Beezley, William H.; MacLachan, Colin M. (2009). Mexicans in Revolution, 1910-1946 : An Introduction. pp. 20–22.

- Womack, John (2011). Zapata and the Mexican Revolution. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

- Adolfo Gilly,The Mexican Revolution

External links