Worldview

A worldview or world-view is the fundamental cognitive orientation of an individual or society encompassing the whole of the individual's or society's knowledge and point of view.[1][2][3][4] A worldview can include natural philosophy; fundamental, existential, and normative postulates; or themes, values, emotions, and ethics.[5]

.jpg)

Worldviews are often taken to operate at a conscious level, directly accessible to articulation and discussion, as opposed to existing at a deeper, pre-conscious level, such as the idea of "ground" in Gestalt psychology and media analysis.

Etymology

The term worldview is a calque of the German word Weltanschauung [ˈvɛltʔanˌʃaʊ.ʊŋ] (![]()

Types of worldviews

There are a number of main classes of worldviews that group similar types of worldviews together. These relate to various aspects of society and individuals' relationships with the world. Note that these distinctions are not always unequivocal: a religion may include economic aspects, a school of philosophy may embody a particular attitude, etc.

Attitudinal

An attitude is an approach to life, a disposition towards certain types of thinking, a way of viewing the world.[7] An attitudinal worldview is a typical attitude that will tend to govern an individual's approach, understanding, thinking, and feelings about things. For instance, people with an optimismic worldview will tend to approach things with a positive attitude, and assume the best.[8] In a metaphor referring to a thirsty person looking at half a glass of water, the attitude is elicited by asking "Is the glass half empty or half full?".

Ideological

Ideologies are sets of beliefs and values that a person or group has for normative reasons,[9] the term is especially used to describe systems of ideas and ideals which form the basis of economic or political theories and resultant policies.[10][11] An ideological worldview arises out of these political and economic beliefs about the world. So capitalists believe that a system that emphasizes private ownership, competition, and the pursuit of profit ends up with the best outcomes.

Philosophical

A school of philosophy is a collection of answers to fundamental questions of the universe, based around common concepts, normally grounded in reason, and often arising from the teachings of an influential thinker.[12][13] The term "philosophy" originates with the Greek, but all world civilizations have been found to have philosophical worldviews within them.[14] A modern example is postmodernists who argue against the grand narratives of earlier schools in favour of pluralism, and epistemological and moral relativism.[15]

Religious

A religion is a system of behaviors and practices, that relate to supernatural, transcendental, or spiritual elements,[16] but the precise definition is debated.[17][18] A religious worldview is one grounded in a religion, either an organized religion or something less codified. So followers of an Abrahamic religion (e.g. Christianity, Islam, Judaism, etc.), will tend to have a set of beliefs and practices from their scriptures that they believe is given to their prophets from God, and their interpretation of those scriptures will define their worldview.

Theories of worldviews

Assessment and comparison

One can think of a worldview as comprising a number of basic beliefs which are philosophically equivalent to the axioms of the worldview considered as a logical or consistent theory. These basic beliefs cannot, by definition, be proven (in the logical sense) within the worldview – precisely because they are axioms, and are typically argued from rather than argued for.[19] However their coherence can be explored philosophically and logically.

If two different worldviews have sufficient common beliefs it may be possible to have a constructive dialogue between them.[20]

On the other hand, if different worldviews are held to be basically incommensurate and irreconcilable, then the situation is one of cultural relativism and would therefore incur the standard criticisms from philosophical realists.[21][22][23] Additionally, religious believers might not wish to see their beliefs relativized into something that is only "true for them".[24][25] Subjective logic is a belief-reasoning formalism where beliefs explicitly are subjectively held by individuals but where a consensus between different worldviews can be achieved.[26]

A third alternative sees the worldview approach as only a methodological relativism, as a suspension of judgment about the truth of various belief systems but not a declaration that there is no global truth. For instance, the religious philosopher Ninian Smart begins his Worldviews: Cross-cultural Explorations of Human Beliefs with "Exploring Religions and Analysing Worldviews" and argues for "the neutral, dispassionate study of different religious and secular systems—a process I call worldview analysis."[27]

The comparison of religious, philosophical or scientific worldviews is a delicate endeavor, because such worldviews start from different presuppositions and cognitive values.[28] Clément Vidal has proposed metaphilosophical criteria for the comparison of worldviews, classifying them in three broad categories:

- objective: objective consistency, scientificity, scope

- subjective: subjective consistency, personal utility, emotionality

- intersubjective: intersubjective consistency, collective utility, narrativity

Linguistics

The Prussian philologist Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767–1835) originated the idea that language and worldview are inextricable. Humboldt saw language as part of the creative adventure of mankind. Culture, language and linguistic communities developed simultaneously and could not do so without one another. In stark contrast to linguistic determinism, which invites us to consider language as a constraint, a framework or a prison house, Humboldt maintained that speech is inherently and implicitly creative. Human beings take their place in speech and continue to modify language and thought by their creative exchanges.

Edward Sapir (1884–1939) also gives an account of the relationship between thinking and speaking in English.[29]

The linguistic relativity hypothesis of Benjamin Lee Whorf (1897–1941) describes how the syntactic-semantic structure of a language becomes an underlying structure for the worldview of a people through the organization of the causal perception of the world and the linguistic categorization of entities. As linguistic categorization emerges as a representation of worldview and causality, it further modifies social perception and thereby leads to a continual interaction between language and perception.[30]

Whorf's hypothesis became influential in the late 1940s, but declined in prominence after a decade. In the 1990s, new research gave further support for the linguistic relativity theory in the works of Stephen Levinson (b. 1947) and his team at the Max Planck institute for psycholinguistics at Nijmegen, Netherlands.[31] The theory has also gained attention through the work of Lera Boroditsky at Stanford University.

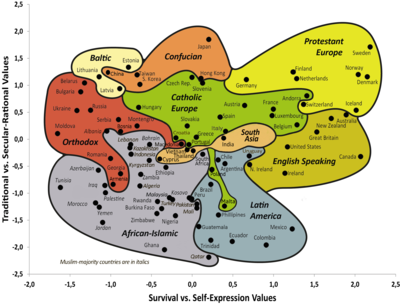

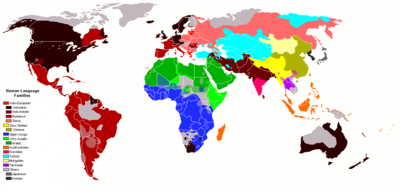

If the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis is correct, the worldview map of the world would be similar to the linguistic map of the world. However, it would also almost coincide with a map of the world drawn on the basis of music across people.[32]

Characteristics

While Leo Apostel and his followers clearly hold that individuals can construct worldviews, other writers regard worldviews as operating at a community level, or in an unconscious way. For instance, if one's worldview is fixed by one's language, as according to a strong version of the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis, one would have to learn or invent a new language in order to construct a new worldview.

According to Apostel,[33] a worldview is an ontology, or a descriptive model of the world. It should comprise these six elements:

- An explanation of the world

- A futurology, answering the question "Where are we heading?"

- Values, answers to ethical questions: "What should we do?"

- A praxeology, or methodology, or theory of action: "How should we attain our goals?"

- An epistemology, or theory of knowledge: "What is true and false?"

- An etiology. A constructed world-view should contain an account of its own "building blocks", its origins and construction.

Weltanschauung and cognitive philosophy

Within cognitive philosophy and the cognitive sciences is the German concept of Weltanschauung. This expression is used to refer to the "wide worldview" or "wide world perception" of a people, family, or person. The Weltanschauung of a people originates from the unique world experience of a people, which they experience over several millennia. The language of a people reflects the Weltanschauung of that people in the form of its syntactic structures and untranslatable connotations and its denotations.[34][35]

The term Weltanschauung is often wrongly attributed to Wilhelm von Humboldt, the founder of German ethnolinguistics. However, as Jürgen Trabant points out, and as James W. Underhill reminds us, Humboldt's key concept was Weltansicht.[36] Weltansicht was used by Humboldt to refer to the overarching conceptual and sensorial apprehension of reality shared by a linguistic community (Nation). On the other hand, Weltanschauung, first used by Kant and later popularized by Hegel, was always used in German and later in English to refer more to philosophies, ideologies and cultural or religious perspectives, than to linguistic communities and their mode of apprehending reality.

In 1911, the German philosopher Wilhelm Dilthey published an essay entitled "The Types of Worldview (Weltanschauung) and their Development in Metaphysics" that became quite influential. Dilthey characterized worldviews as providing a perspective on life that encompasses the cognitive, evaluative, and volitional aspects of human experience. Although worldviews have always been expressed in literature and religion, philosophers have attempted to give them conceptual definition in their metaphysical systems. On that basis, Dilthey found it possible to distinguish three general recurring types of worldview. The first of these he called naturalism because it gives priority to the perceptual and experimental determination of what is and allows contingency to influence how we evaluate and respond to reality. Naturalism can be found in Democritus, Hobbes, Hume and many other modern philosophers. The second type of worldview is called the idealism of freedom and is represented by Plato, Descartes, Kant, and Bergson among others. It is dualistic and gives primacy to the freedom of the will. The organizational order of our world is structured by our mind and the will to know. The third type is called objective idealism and Dilthey sees it in Heraclitus, Parmenides, Spinoza, Leibniz and Hegel. In objective idealism the ideal does not hover above what is actual but inheres in it. This third type of worldview is ultimately monistic and seeks to discern the inner coherence and harmony among all things. Dilthey thought it is impossible to come up with a universally valid metaphysical or systematic formulation of any of these worldviews, but regarded them as useful schema for his own more reflective kind of life philosophy. See Makkreel and Rodi, Wilhelm Dilthey, Selected Works, volume 6, 2019.

Anthropologically, worldviews can be expressed as the "fundamental cognitive, affective, and evaluative presuppositions a group of people make about the nature of things, and which they use to order their lives."[37]

If it were possible to draw a map of the world on the basis of Weltanschauung,[32] it would probably be seen to cross political borders—Weltanschauung is the product of political borders and common experiences of a people from a geographical region,[32] environmental-climatic conditions, the economic resources available, socio-cultural systems, and the language family.[32] (The work of the population geneticist Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza aims to show the gene-linguistic co-evolution of people).

Worldview is used very differently by linguists and sociologists. It is for this reason that James W. Underhill suggests five subcategories: world-perceiving, world-conceiving, cultural mindset, personal world, and perspective.[36][38][39]

Terror management theory

.jpg)

A worldview, according to terror management theory (TMT), serves as a buffer against death anxiety.[40] It is theorized that living up to the ideals of one's worldview provides a sense of self-esteem which provides a sense of transcending the limits of human life (e.g. literally, as in religious belief in immortality; symbolically, as in art works or children to live on after one's death, or in contributions to one's culture).[40] Evidence in support of terror management theory includes a series of experiments by Jeff Schimel and colleagues in which a group of Canadians found to score highly on a measure of patriotism were asked to read an essay attacking the dominant Canadian worldview.[40]

Using a test of death-thought accessibility (DTA), involving an ambiguous word completion test (e.g. "COFF__" could either be completed as either "COFFEE" or "COFFIN" or "COFFER"), participants who had read the essay attacking their worldview were found to have a significantly higher level of DTA than the control group, who read a similar essay attacking Australian cultural values. Mood was also measured following the worldview threat, to test whether the increase in death thoughts following worldview threat were due to other causes, for example, anger at the attack on one's cultural worldview.[40] No significant changes on mood scales were found immediately following the worldview threat.[40]

To test the generalisability of these findings to groups and worldviews other than those of nationalistic Canadians, Schimel et al conducted a similar experiment on a group of religious individuals whose worldview included that of creationism.[40] Participants were asked to read an essay which argued in support of the theory of evolution, following which the same measure of DTA was taken as for the Canadian group.[40] Religious participants with a creationist worldview were found to have a significantly higher level of death-thought accessibility than those of the control group.[40]

Goldenberg et al found that highlighting the similarities between humans and other animals increases death-thought accessibility, as does attention to the physical rather than meaningful qualities of sex.[41]

Causality

A unidirectional view of causality is present in some monotheistic views of the world with a beginning and an end and a single great force with a single end (e.g., Christianity and Islam), while a cyclic worldview of causality is present in religious traditions which are cyclic and seasonal and wherein events and experiences recur in systematic patterns (e.g., Zoroastrianism, Mithraism and Hinduism). These worldviews of causality not only underlie religious traditions but also other aspects of thought like the purpose of history, political and economic theories, and systems like democracy, authoritarianism, anarchism, capitalism, socialism and communism.

With the development of science came a clockwork universe of regular operation according to principle, this idea was very popular among deists during the Enlightenment. But later developments in science put this deterministic picture in doubt.[42]

Some forms of philosophical naturalism and materialism reject the validity of entities inaccessible to natural science. They view the scientific method as the most reliable model for building an understanding of the world.

The term worldview denotes a comprehensive set of opinions, seen as an organic unity, about the world as the medium and exercise of human existence. worldview serves as a framework for generating various dimensions of human perception and experience like knowledge, politics, economics, religion, culture, science and ethics. For example, worldview of causality as uni-directional, cyclic, or spiral generates a framework of the world that reflects these systems of causality.

Religion

Nishida Kitaro wrote extensively on "the Religious Worldview" in exploring the philosophical significance of Eastern religions.[43]

According to Neo-Calvinist David Naugle's World view: The History of a Concept, "Conceiving of Christianity as a worldview has been one of the most significant developments in the recent history of the church."[44]

The Christian thinker James W. Sire defines a worldview as "a commitment, a fundamental orientation of the heart, that can be expressed as a story or in a set of presuppositions (assumptions which may be true, partially true, or entirely false) which we hold (consciously or subconsciously, consistently or inconsistently) about the basic construction of reality, and that provides the foundation on which we live and move and have our being." He suggests that "we should all think in terms of worldviews, that is, with a consciousness not only of our own way of thought but also that of other people, so that we can first understand and then genuinely communicate with others in our pluralistic society."[45]

The commitment mentioned by James W. Sire can be extended further. The worldview increases the commitment to serve the world. With the change of a person's view towards the world, he/she can be motivated to serve the world. This serving attitude has been illustrated by Tareq M Zayed as the 'Emancipatory Worldview' in his writing "History of emancipatory worldview of Muslim learners".[46]

David Bell has also raised questions on religious worldviews for the designers of superintelligences – machines much smarter than humans.[47]

Classification systems for worldviews

A number of modern thinkers have created and attempted to popularize various classification systems for worldviews, to various degrees of success. These systems often hinge on a few key questions.

Roland Muller's classification of cultural worldviews

From across the world across all of the cultures, Roland Muller has suggested that cultural worldviews can be broken down into three separate worldviews.[48] It is not simple enough to say that each person is one of these three cultures. Instead, each individual is a mix of the three. For example, a person may be raised in a Power–Fear society, in an Honor–Shame family, and go to school under a Guilt–Innocence system.

- Guilt–Innocence: In a Guilt–Innocence focused culture, schools focus on deductive reasoning, cause and effect, good questions, and process. Issues are often seen as black and white. Written contracts are paramount. Communication is direct, and can be blunt.[49]

- Honor–Shame: Societies with a predominantly Honor–Shame worldviews teach children to make honorable choices according to the situations they find themselves in. Communication, interpersonal interaction, and business dealings are very relationship-driven, with every interaction having an effect on the Honor–Shame status of the participants. In an Honor–Shame society the crucial objective is to avoid shame and to be viewed honorably by other people. The Honor–Shame paradigm is especially strong in most regions of Asia.[50]

- Power–Fear: Some cultures can be seen very clearly in operating under a Power–Fear worldview. In these cultures it is very important to assess the people around you and know where they fall in line according to their level of power. This can be used for good or for bad. A benevolent king rules with power and his citizens fully support him wielding that power. On the converse, a ruthless dictator can use his power to create a culture of fear where his citizens are oppressed.

Michael Lind's classification of American political worldviews

According to Michael Lind, "a worldview is a more or less coherent understanding of the nature of reality, which permits its holders to interpret new information in light of their preconceptions. Clashes among worldviews cannot be ended by a simple appeal to facts. Even if rival sides agree on the facts, people may disagree on conclusions because of their different premises."[51] This is why politicians often seem to talk past one another, or ascribe different meanings to the same events. Tribal or national wars are often the result of incompatible worldviews. Lind has organized American political worldviews into five categories:

- Green Malthusianism

- Libertarian isolationism

- Neoliberal globalism

- Populist nationalism

- Social democracy

Lind argues that even though not all people will fit neatly into only one category or the other, their core worldview shape how they frame their arguments.[51]

James Anderson's evangelical classification of worldviews

James Anderson says that a worldview is an overall "philosophical view, an all-encompassing perspective on everything that exists and matters to us".[52] He breaks worldviews down between (evangelical) "Christian" and "non-Christian." He lists the following non-Christian worldviews:

As such, his system focuses on the similarities and differences of worldviews to evangelicalism.[52]

Related terms

Belief systems

A belief system is the set of interrelated beliefs held by an individual or society.[53] It can be thought of as a list of beliefs or axioms that the believer considers true or false. A belief system is similar to a worldview, but is based around conscious beliefs.[54]

Belief systems became increasingly important to 20th century philosophy for a number of reasons, such as widespread contact between cultures, and the failure of some aspects of the Enlightenment project, such as the rationalist project of attaining all truth by reason alone. Mathematical logic showed that fundamental choices of axioms were essential in deductive reasoning[55] and that, even having chosen axioms not everything that was true in a given logical system could be proven.[56] Some philosophers believe the problems extend to "the inconsistencies and failures which plagued the Enlightenment attempt to identify universal moral and rational principles";[57] although Enlightenment principles such as universal suffrage and the universal declaration of human rights are accepted, if not taken for granted, by many.[58]

Conventional wisdoms

Conventional wisdom is the body of ideas or explanations generally accepted as true by the general public, or by believers in a worldview.[59] It is the set of underlying assumptions that make up the base of a body of shared ideas, like a worldview.

Folk-epics

As natural language becomes manifestations of world perception, the literature of a people with common worldview emerges as holistic representations of the wide world perception of the people. Thus the extent and commonality between world folk-epics becomes a manifestation of the commonality and extent of a worldview.[60]

Epic poems are shared often by people across political borders and across generations. Examples of such epics include the Nibelungenlied of the Germanic people, the Iliad for the Ancient Greeks and Hellenized societies, the Silappadhikaram of the Tamil people, the Ramayana and Mahabharata of the Hindus, the Epic of Gilgamesh of the Mesopotamian–Sumerian civilization and the people of the Fertile Crescent at large, The Book of One Thousand and One Nights (Arabian nights) of the Arab world, and the Sundiata epic of the Mandé people.[60][61][62]

Geists

A geist is a German concept, similar to English "spirit", here referring to the spirit of a group or age.[63] It is the common character or invisible force motivating a collection of people to act in certain ways. It is sometimes used in philosophy, but can also pragmatically refer to fads or fashions. The weltgeist is the geist of the world,[64] a volksgeist is the geist of a nation or people,[65] and a zeitgeist is the geist of an age.[66] Geists are similar to worldviews in that they underlie the character of a people, but are more ineffable in their understanding.

Memeplexes

A memeplex is a group of memes, within the theory of memetics. This is a way of approaching ideas and worldviews using the theory of Universal Darwinism. Like the gene complexes found in biology, memeplexes are groups of memes, or worldviews, that are often found present together. Memes were first suggested in Richard Dawkins' book The Selfish Gene.[67]

Mindsets

A mindset is a set of assumptions, methods, or notations held by one or more people or groups of people.[68] The idea is common to decision theory and general systems theory. A mindset is often seen to arise out of a person's worldview, a mindset is a temporary attitude guided by a person's worldview.[4]

Paradigms

Paradigms are outstandingly clear patterns or archetypes, the typifying example of a particular model or idea.[69] Especially in science and philosophy, a paradigm is a distinct set of concepts or thought patterns, including theories, research methods, postulates, and standards for what constitutes legitimate contributions to a field.

Reality tunnels

A reality tunnel is a theoretical subconscious set of mental filters formed from beliefs and experiences, every individual interprets the same world differently, hence "Truth is in the eye of the beholder". The idea being that an individual's perceptions are influenced or determined by their worldview. The idea does not necessarily imply that there is no objective truth; rather that our access to it is mediated through our senses, experience, conditioning, prior beliefs, and other non-objective factors. The term can also apply to groups of people united by beliefs: we can speak of the fundamentalist Christian reality tunnel or the ontological naturalist reality tunnel. A parallel can be seen in the psychological concept of confirmation bias—the human tendency to notice and assign significance to observations that confirm existing beliefs, while filtering out or rationalizing away observations that do not fit with prior beliefs and expectations.[70]

Social norms

Social norms are collective representations of acceptable behavior within a group,[71] including values, customs, and traditions.[72] These represent individuals' understanding, or worldview, in regards what others in their group do, and what they think that they ought to do.[73]

See also

- Attitude polarization

- Basic belief – The axioms under the epistemological view called foundationalism

- Belief – Psychological state of holding a proposition or premise to be true

- Bayesian network, also known as Belief networks – Statistical model

- Christian worldview

- Cognitive bias – Systematic pattern of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment

- Conformity

- Contemplation – Profound thinking about something

- Context (language use) – Objects or conditions associated with an event or use of a term that provide resources for its appropriate interpretation

- Conventional wisdom

- Cultural bias – Interpretation and judgement of phenomena by the standards of one's culture

- Cultural identity

- Eschatology – Part of theology concerned with the final events of history, or the ultimate destiny of humanity

- Observation, also known as Extrospection – Active acquisition of information from a primary source

- Framing (social sciences) – Effect of how information is presented on perception

- Ideology – Set of beliefs and values attributed to a person or group of persons

- Life stance

- Mental model – Explanation of someone's thought process about how something works in the real world

- Mental representation – Hypothetical internal cognitive symbol that represents external reality

- Metaknowledge

- Metanarrative – A theory that gives comprehensive interpretation to events or experiences based on a claim of universal truth

- Metaphysics – Branch of philosophy dealing with the nature of reality

- Mindset

- Mythology

- Ontology – Branch of philosophy concerned with concepts such as existence, reality, being, becoming, as well as the basic categories of existence and their relations

- Organizing principle

- Paradigm – Distinct concepts or thought patterns or archetypes

- Perspective

- Philosophy – Study of the truths and principles of being, knowledge, or conduct

- Psycholinguistics – Study of relations between psychology and language

- Reality – Sum or aggregate of all that is real or existent

- Reality tunnel

- Religion – Sacred belief system

- Schema (psychology)

- Scientific modelling

- Scientism

- Set (psychology)

- Social justice – Concept of fair and just relations between the individual and society

- Social norm

- Social reality

- Social constructionism, also known as Socially constructed reality – Theory that shared understandings of the world create shared assumptions about reality

- Subjective logic

- Truth – A term meaning "in accord with fact or reality"

- Umwelt – Bological foundations central to the study of communication and signification

- Value system

References

- "world-view noun – Definition, pictures, pronunciation and usage notes – Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary at OxfordLearnersDictionaries.com". www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com.

- "Worldview – Definition of Worldview by Merriam-Webster". Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- Bell, Kenton (26 September 2014). "worldview definition – Open Education Sociology Dictionary". Open Education Sociology Dictionary. Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- Funk, Ken (2001-03-21). "What is a Worldview?". Retrieved 2019-12-10.

- Palmer, Gary B. (1996). Toward A Theory of Cultural Linguistics. University of Texas Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-292-76569-6.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- "Attitude – Definition of Attitude by Merriam-Webster". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2019-12-13.

- "Definition of optimism", Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster, archived from the original on November 15, 2017, retrieved November 14, 2017

- Honderich, Ted (1995). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866132-0.

- Oxford Dictionaries definition; retrieved 20/02/2019 definition/ideology

- Van Dijk, Teun A. (2013). "Ideology and Discourse". In Freeden, Michael; Stears, Marc (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies. OUP Oxford. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199585977.013.007. ISBN 978-0-19-958597-7.

- "PHILOSOPHY – meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 2019-12-20.

- "Philosophy – Definition of Philosophy by Merriam-Webster". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2019-12-20.

- Edelglass, William; Garfield, Jay L. (2011). "Introduction". In Garfield, Jay L.; Edelglass, William (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy. OUP USA. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195328998.003.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-532899-8.

- "Postmodern – Definition of Postmodern by Merriam-Webster". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2019-12-20.

- "Religion – Definition of Religion by Merriam-Webster". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2019-12-16.

- Morreall, John; Sonn, Tamara (2013). "Myth 1: All Societies Have Religions". 50 Great Myths of Religion. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 12–17. ISBN 978-0-470-67350-8.

- Nongbri, Brent (2013). Before Religion: A History of a Modern Concept. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15416-0.

- See for example Daniel Hill and Randal Rauser: Christian Philosophy A–Z Edinburgh University Press (2006) ISBN 978-0-7486-2152-1 p200

- In the Christian tradition this goes back at least to Justin Martyr's Dialogues with Trypho, A Jew, and has roots in the debates recorded in the New Testament For a discussion of the long history of religious dialogue in India, see Amartya Sen's The Argumentative Indian

- Cognitive Relativism, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The problem of self-refutation is quite general. It arises whether truth is relativized to a framework of concepts, of beliefs, of standards, of practices.Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Friesian School on Relativism

- Pope Benedict warns against relativism

- Ratzinger, J. Relativism, the Central Problem for Faith Today

- Jøsang, Audun (21 November 2011). "A Logic For Uncertain Probabilities" (PDF). International Journal of Uncertainty, Fuzziness and Knowledge-Based Systems. 09 (3): 279–311. doi:10.1142/S0218488501000831.

- Ninian Smart Worldviews: Crosscultural Explorations of Human Beliefs (3rd Edition) ISBN 0-13-020980-5 p14

- Vidal, Clément (April 2012). "Metaphilosophical Criteria for Worldview Comparison". Metaphilosophy. 43 (3): 306–347. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.508.631. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9973.2012.01749.x.

- Fadul, Jose (2014). Encyclopedia of Theory and Practice in Psychotherapy and Counseling. p. 347. ISBN 978-1-312-34920-9.

Edward Sapir also gives an account of the significant relationship between thinking and speaking in English.

- Kay, P.; Kempton, W. (1984). "What is the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis?". American Anthropologist. 86 (1): 65–79. doi:10.1525/aa.1984.86.1.02a00050. JSTOR 679389.

- "Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics". Archived from the original on September 9, 2004. Retrieved September 8, 2004.

- Whorf, Benjamin Lee (1964) [1st pub. 1956]. Carroll, John Bissell (ed.). Language, Thought, and Reality. Selected Writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf. Cambridge, Mass.: Technology Press of Massachusetts Institute of Technology. ISBN 978-0-262-73006-8. Pp. 25, 36, 29-30, 242, 248.

- Diederik Aerts, Leo Apostel, Bart de Moor, Staf Hellemans, Edel Maex, Hubert van Belle & Jan van der Veken (1994). "World views. From Fragmentation to Integration". VUB Press. Translation of Apostel and Van der Veken 1991 with some additions. – The basic book of World Views, from the Center Leo Apostel.

- "Weltanschauung – Definition of Weltanschauung by Merriam-Webster". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2019-12-17.

- "Worldview (philosophy) – Encyclopedia.com". Encyclopedia.com. 2019-12-14. Retrieved 2019-12-17.

- Underhill, James W. (2009). Humboldt, Worldview and Language (Transferred to digital print. ed.). Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0748638420.

- Hiebert, Paul G. Transforming Worldviews: an anthropological understanding of how people change. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Academic, 2008

- Underhill, James W. (2011). Creating worldviews : metaphor, ideology and language. Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0748679096.

- Underhill, James W. (2012). Ethnolinguistics and Cultural Concepts: truth, love, hate & war. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107532847.

- Schimel, Jeff; Hayes, Joseph; Williams, Todd; Jahrig, Jesse (2007). "Is death really the worm at the core? Converging evidence that worldview threat increases death-thought accessibility". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 92 (5): 789–803. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.789. PMID 17484605.

- Goldenberg, Jamie L.; Cox, Cathy R.; Pyszczynski, Tom; Greenberg, Jeff; Solomon, Sheldon (November 2002). "Understanding human ambivalence about sex: The effects of stripping sex of meaning". Journal of Sex Research. 39 (4): 310–320. doi:10.1080/00224490209552155. PMID 12545414.

- Danielson, Dennis Richard (2000). The Book of the Cosmos: Imagining the Universe from Heraclitus to Hawking. Basic Books. ISBN 0738202479.

- Indeed Kitaro's final book is Last Writings: Nothingness and the Religious Worldview

- David K. Naugle Worldview: The History of a Concept ISBN 0-8028-4761-7 page 4

- James W. Sire The Universe Next Door: A Basic World view Catalog p15–16 (text readable at Amazon.com)

- Zayed, Tareq M. "History of emancipatory worldview of Muslim learners". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Bell, David (2016). Superintelligence and World-views: Putting the Spotlight on Some Important Issues. Guildford, Surrey, UK: Grosvenor House Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781786237668. OCLC 962016344.

- Muller, Roland (2001). Honor and Shame. Xlibris; 1st edition. ISBN 978-0738843162.

- "Three Colors of Worldview". KnowledgeWorkx. Retrieved 2016-02-25.

- Blankenbugh, Marco (2013). Inter-Cultural Intelligence: From Surviving to Thriving in the Global Space. BookBaby. ISBN 9781483511528.

- Lind, Michael (12 January 2011). "The five worldviews that define American politics". Salon Magazine. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- Anderson, James (2017-06-21). "What Is a Worldview?". Ligonier Ministries. Retrieved 2019-12-20.

- "Belief system definition and meaning – Collins English Dictionary". Retrieved 2019-12-19.

- Rettig, Tim (2017-12-08). "Belief Systems: what they are and how they affect you". Medium. Retrieved 2019-12-19.

- Not just in the obvious sense that you need axioms to prove anything, but the fact that for example the Axiom of choice and Axiom S5, although widely regarded as correct, were in some sense optional.

- see Godel's incompleteness theorem and discussion in e.g. John Lucas's The Freedom of the Will

- Thus Alister McGrath in The Science of God p 109 citing in particular Alasdair MacIntyre's Whose Justice? Which Rationality? – he also cites Nicholas Wolterstorff and Paul Feyerabend

- "Governments in a democracy do not grant the fundamental freedoms enumerated by Jefferson; governments are created to protect those freedoms that every individual possesses by virtue of his or her existence. In their formulation by the Enlightenment philosophers of the 17th and 18th centuries, inalienable rights are God-given natural rights. These rights are not destroyed when civil society is created, and neither society nor government can remove or "alienate" them."US Gov website on democracy Archived December 1, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Conventional Wisdom – Definition of Conventional Wisdom by Merriam-Webster". Retrieved 2019-12-13.

- "World Folk-epics". Language is a Virus. Retrieved 2019-12-17.

- "Epic poetry". Language is a Virus. Retrieved 2019-12-17.

- "The 20 Greatest Epic Poems of All Time". Qwiklit. 2013-09-10. Retrieved 2019-12-17.

- "Geist dictionary definition – geist defined". www.yourdictionary.com. Retrieved 2019-12-17.

- "Definition/Meaning of Weltgeist". EngYes. Retrieved 2019-12-17.

- "Volksgeist – Encyclopedia.com". Encyclopedia.com. 2019-11-26. Retrieved 2019-12-17.

- "Zeitgeist – Definition of Zeitgeist by Merriam-Webster". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2019-12-17.

- Dawkins, Richard (1989), The Selfish Gene (2 ed.), Oxford University Press, p. 192, ISBN 978-0-19-286092-7,

We need a name for the new replicator, a noun that conveys the idea of a unit of cultural transmission, or a unit of imitation. 'Mimeme' comes from a suitable Greek root, but I want a monosyllable that sounds a bit like 'gene'. I hope my classicist friends will forgive me if I abbreviate mimeme to meme. If it is any consolation, it could alternatively be thought of as being related to 'memory', or to the French word même. It should be pronounced to rhyme with 'cream'.

- "MINDSET – meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary". Retrieved 2019-12-10.

- "Definition of paradigm by Merriam-Webster". Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- "Introduction to Reality Tunnels: A Tool for Understanding the Postmodern World". 2017-01-21. Retrieved 2019-12-06.

- Lapinski, M. K. (1 May 2005). "An Explication of Social Norms". Communication Theory. 15 (2): 127–147. doi:10.1093/ct/15.2.127.

- Sherif, M. (1936). The psychology of social norms. NewYork: Harper.

- Cialdini, Robert B. (22 June 2016). "Crafting Normative Messages to Protect the Environment". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 12 (4): 105–109. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.579.5154. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.01242.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Worldview |

| Wikiversity has learning resources about Exploring Worldviews |

- GLOGO – Global Governance System for Planet Earth at think tank Gold Mercury International

- Apostel, Leo and Van der Veken, Jan. (1991) Wereldbeelden, DNB/Pelckmans.

- Wikibook:The scientific world view

- Wiki Worldview Themes: A Structure for Characterizing and Analyzing Worldviews includes links to nearly 400 Wikipedia articles

- "You are what you speak" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2009-09-20.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) (5.15 MB) – a 2002 essay on research in linguistic relativity (Lera Boroditsky)

- "Cobern, W. World View, Metaphysics, and Epistemology" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2016-03-03.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) (50.3 KB)

- inTERRAgation.com—A documentary project. Collecting and evaluating answers to "the meaning of life" from around the world.

- The God Contention—Comparing various worldviews, faiths, and religions through the eyes of their advocates.

- Cole, Graham A., Do Christians have a Worldview? A paper examining the concept of worldview as it relates to and has been used by Christianity. Contains a helpful annotated bibliography.

- World View article on the Principia Cybernetica Project

- Pogorskiy, E. (2015). Using personalisation to improve the effectiveness of global educational projects. E-Learning and Digital Media, 12(1), 57–67.

- Worldviews – An Introduction from Project Worldview

- "Studies on World Views Related to Science" (list of suggested books and resources) from the American Scientific Affiliation (a Christian perspective)

- Eugene Webb, Worldview and Mind: Religious Thought and Psychological Development. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2009.

- Benjamin Gal-Or, “Cosmology, Physics and Philosophy”, Springer Verlag, 1981, 1983, 1987, ISBN 0-387-90581-2, ISBN 0-387-96526-2.

- Беляев И.А. Человек и его мироотношение. Сообщение 1. Мироотношение и мировоззрение / И.А. Беляев // Политематический сетевой электронный научный журнал Кубанского государственного аграрного университета (Научный журнал КубГАУ) [Электронный ресурс]. – Краснодар: КубГАУ, 2011. – №09(73). С. 310–319. – Режим доступа: http://ej.kubagro.ru/2011/09/pdf/29.pdf (https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=17087744).