Crowd manipulation

Crowd manipulation is the intentional use of techniques based on the principles of crowd psychology to engage, control, or influence the desires of a crowd in order to direct its behavior toward a specific action.[1] This practice is common to religion, politics and business and can facilitate the approval or disapproval or indifference to a person, policy, or product. The ethicality of crowd manipulation is commonly questioned.

Crowd manipulation differs from propaganda although they may reinforce one another to produce a desired result. If propaganda is "the consistent, enduring effort to create or shape events to influence the relations of the public to an enterprise, idea or group",[2] crowd manipulation is the relatively brief call to action once the seeds of propaganda (i.e. more specifically "pre-propaganda"[3]) are sown and the public is organized into a crowd. The propagandist appeals to the masses, even if compartmentalized, whereas the crowd manipulator appeals to a segment of the masses assembled into a crowd in real time. In situations such as a national emergency, however, a crowd manipulator may leverage mass media to address the masses in real time as if speaking to a crowd.[4]

Crowd manipulation also differs from crowd control, which serves a security function. Local authorities use crowd-control methods to contain and disperse crowds and to prevent and respond to unruly and unlawful acts such as rioting and looting.[5]

Function and morality

The crowd manipulator engages, controls, or influences crowds without the use of physical force, although his goal may be to instigate the use of force by the crowd or by local authorities. Prior to the American War of Independence, Samuel Adams provided Bostonians with "elaborate costumes, props, and musical instruments to lead protest songs in harborside demonstrations and parades through Boston's streets." If such crowds provoked British authorities to violence, as they did during the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770, Adams would write, produce, and disperse sensationalized accounts of the incidents to stir discontent and create unity among the American colonies.[6] The American way of manipulation may be classified as a tool of soft power, which is "the ability to get what you want through attraction rather than coercion or payments".[7] Harvard professor Joseph Nye coined the term in the 1980s, although he did not create the concept. The techniques used to win the minds of crowds were examined and developed notably by Quintilian in his training book, Institutio oratoria and by Aristotle in Rhetoric. Known origins of crowd manipulation go as far back as the 5th century BC, where litigants in Syracuse sought to improve their persuasiveness in court.[8][9]

The verb "manipulate" can convey negativity, but it does not have to do so. According to Merriam Webster's Dictionary, for example, to "manipulate" means "to control or play upon by artful, unfair, or insidious means especially to one's own advantage."[10] This definition allows, then, for the artful and honest use of control for one's advantage. Moreover, the actions of a crowd need not be criminal in nature. Nineteenth-century social scientist Gustave Le Bon wrote:

It is crowds rather than isolated individuals that may be induced to run the risk of death to secure the triumph of a creed or an idea, that may be fired with enthusiasm for glory and honour, that are led on--almost without bread and without arms, as in the age of the Crusades—to deliver the tomb of Christ from the infidel, or, as in [1793], to defend the fatherland. Such heroism is without doubt somewhat unconscious, but it is of such heroism that history is made. Were peoples only to be credited with the great actions performed in cold blood, the annals of the world would register but few of them.[11]

Edward Bernays, the so-called "Father of Public Relations", believed that public manipulation was not only moral, but a necessity. He argued that "a small, invisible government who understands the mental processes and social patterns of the masses, rules public opinion by consent." This is necessary for the division of labor and to prevent chaos and confusion. "The voice of the people expresses the mind of the people, and that mind is made up for it by the group leaders in whom it believes and by those persons who understand the manipulation of public opinion", wrote Bernays.[12] He also wrote, "We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of. This is a logical result of the way in which our democratic society is organized."

Others argue that some techniques are not inherently evil, but instead are philosophically neutral vehicles. Lifelong political activist and former Ronald Reagan White House staffer Morton C. Blackwell explained in a speech titled, "People, Parties, and Power":

Being right in the sense of being correct is not sufficient to win. Political technology determines political success. Learn how to organize and how to communicate. Most political technology is philosophically neutral. You owe it to your philosophy to study how to win.[13]

In brief, manipulators with different ideologies can employ successfully the same techniques to achieve ends that may be good or bad. Crowd manipulation techniques offers individuals and groups a philosophically neutral means to maximize the effect of their messages.

In order to manipulate a crowd, one should first understand what is meant by a crowd, as well as the principles that govern its behavior.

Crowds and their behavior

The word "crowd", according to Merriam-Webster's Dictionary, refers to both "a large number of persons especially when collected together" (as in a crowded shopping mall) and "a group of people having something in common [as in a habit, interest, or occupation]."[14] Philosopher G.A. Tawny defined a crowd as "a numerous collection of people who face a concrete situation together and are more or less aware of their bodily existence as a group. Their facing the situation together is due to common interests and the existence of common circumstances which give a single direction to their thoughts and actions." Tawney discussed in his work "The Nature of Crowds" two main types of crowds:

Crowds may be classified according to the degree of definiteness and constancy of this consciousness. When it is very definite and constant the crowd may be called homogeneous, and when not so definite and constant, heterogeneous. All mobs belong to the homogeneous class, but not all homogeneous crowds are mobs. ... Whether a given crowd belong to the one group or the other may be a debatable question, and the same crowd may imperceptibly pass from one to the other.[15]

In a 2001 study, the Institute for Non-Lethal Defense Studies at Pennsylvania State University defined a crowd more specifically as "a gathering of a multitude of individuals and small groups that have temporarily assembled. These small groups are usually comprised of friends, family members, or acquaintances."

A crowd may display behavior that differs from the individuals who compose it. Several theories have emerged in the 19th century and early 20th century to explain this phenomenon. These collective works contribute to the "classic theory" of crowd psychology. In 1968, however, social scientist Dr. Carl Couch of the University of Liverpool refuted many of the stereotypes associated with crowd behavior as described by classic theory. His criticisms are supported widely in the psychology community but are still being incorporated as a "modern theory" into psychological texts.[16] A modern model, based on the "individualistic" concept of crowd behavior developed by Floyd Allport in 1924, is the Elaborated Social Identity Model (ESIM).[17]

Classic theory

French philosopher and historian Hippolyte Taine provided in the wake of the Franco Prussian War of 1871 the first modern account of crowd psychology. Gustave Le Bon developed this framework in his 1895 book, Psychologie des Foules. He proposed that French crowds during the 19th century were essentially excitable, irrational mobs easily influenced by wrongdoers.[18] He postulated that the heterogeneous elements which make up this type of crowd essentially form a new being, a chemical reaction of sorts in which the crowd's properties change. He wrote:

Under certain given circumstances, and only under those circumstances, an agglomeration of men presents new characteristics very different from those of the individuals composing it. The sentiments and ideas of all the persons in the gathering take one and the same direction, and their conscious personality vanishes. A collective mind is formed, doubtless transitory, but presenting very clearly defined characteristics.

Le Bon observed several characteristics of what he called the "organized" or "psychological" crowd, including:

- submergence or the disappearance of a conscious personality and the appearance of an unconscious personality (aka "mental unity"). This process is aided by sentiments of invincible power and anonymity which allow one to yield to instincts which he would have kept under restraint (i.e. Individuality is weakened and the unconscious "gains the upper hand");

- contagion ("In a crowd every sentiment and act is contagious, and contagious to such a degree that an individual readily sacrifices his personal interest to the collective interest."); and

- suggestibility as the result of a hypnotic state. "All feelings and thoughts are bent in the direction determined by the hypnotizer" and the crowd tends to turn these thoughts into acts.[11]

In sum, the classic theory contends that:

- "[Crowds] are unified masses whose behaviors can be categorized as active, expressive, acquisitive or hostile."

- "[Crowd] participants [are] given to spontaneity, irrationality, loss of self-control, and a sense of anonymity."[19]

Modern theory

Critics of the classic theory contend that it is seriously flawed in that it decontextualises crowd behavior, lacks sustainable empirical support, is biased, and ignores the influence of policing measures on the behavior of the crowd.[20]

In 1968, Dr. Carl J. Couch examined and refuted many classic-theory stereotypes in his article, "Collective Behavior: An Examination of Some Stereotypes." Since then, other social scientists have validated much of his critique. Knowledge from these studies of crowd psychology indicate that:

- "Crowds are not homogeneous entities" but are composed "of a minority of individuals and a majority of small groups of people who are acquainted with one another."

- "Crowd participants are [neither] unanimous in their motivation" nor to one another. Participants "seldom act in unison, and if they do, that action does not last long."

- "Crowds do not cripple individual cognition" and "are not uniquely distinguished by violence or disorderly actions."

- "Individual attitudes and personality characteristics", as well as "socioeconomic, demographic and political variables are poor predictors of riot intensity and individual participation."

According to the aforementioned 2001 study conducted by Penn State University's Institute for Non-Lethal Defense Technologies, crowds undergo a process that has a "beginning, middle, and ending phase." Specifically:

- The assembling process

- This phase includes the temporary assembly of individuals for a specific amount of time. Evidence suggests that assembly occurs most frequently by means of an "organized mobilization method" but can also occur by "impromptu process" such as word of mouth by non-official organizers.

- The temporary gathering

- In this phase, individuals are assembled and participate in both individual and "collective actions." Rarely do all individuals in a crowd participate, and those who do participate do so by choice. Participation furthermore appears to vary based on the type and purpose of the gathering, with religious services experiencing "greater participation" (i.e. 80-90%).

- The dispersing process

- In the final phase, the crowd's participants disperse from a "common location" to "one or more alternate locations."

A "riot" occurs when "one or more individuals within a gathering engage in violence against person or property." According to U.S. and European research data from 1830 to 1930 and from the 1960 to the present, "less than 10 percent of protest demonstrations have involved violence against person or property", with the "celebration riot" as the most frequent type of riot in the United States.[21]

Elaborated social identity model (ESIM)

A modern model has also been developed by Steve Reicher, John Drury, and Clifford Stott[22] which contrasts significantly from the "classic theory" of crowd behavior. According to Clifford Stott of the University of Leeds:

The ESIM has at its basis the proposition that a component part of the self concept determining human social behaviour derives from psychological membership of particular social categories (i.e., an identity of a unique individual), crowd participants also have a range of social identities which can become salient within the psychological system referred to as the 'self.' Collective action becomes possible when a particular social identity is simultaneously salient and therefore shared among crowd participants.

Stott's final point differs from the "submergence" quality of crowds proposed by Le Bon, in which the individual's consciousness gives way to the unconsciousness of the crowd. ESIM also considers the effect of policing on the behavior of the crowd. It warns that "the indiscriminate use of force would create a redefined sense of unity in the crowd in terms of the illegitimacy of and opposition to the actions of the police." This could essentially draw the crowd into conflict despite the initial hesitancy of the individuals in the crowd.[23]

Planning and technique

Crowd manipulation involves several elements, including: context analysis, site selection, propaganda, authority, and delivery.

Context analysis

History suggests that the socioeconomic and political context and location influence dramatically the potential for crowd manipulation. Such time periods in America included:

- Prelude to the American Revolution (1763–1775), when Britain imposed heavy taxes and various restrictions upon its thirteen North American colonies;[24]

- Roaring Twenties (1920–1929), when the advent of mass production made it possible for everyday citizens to purchase previously considered luxury items at affordable prices. Businesses that utilized assembly-line manufacturing were challenged to sell large numbers of identical products;[25]

- The Great Depression (1929–1939), when a devastating stock market crash disrupted the American economy, caused widespread unemployment; and

- The Cold War (1945–1989), when Americans faced the threat of nuclear war and participated in the Korean War, the greatly unpopular Vietnam War, the Civil Rights Movement, the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Internationally, time periods conducive to crowd manipulation included the Interwar Period (i.e. following the collapse of the Austria-Hungarian, Russian, Ottoman, and German empires) and Post-World War II (i.e. decolonization and collapse of the British, German, French, and Japanese empires).[26] The prelude to the collapse of the Soviet Union provided ample opportunity for messages of encouragement. The Solidarity Movement began in the 1970s thanks in part to leaders like Lech Walesa and U.S. Information Agency programming.[27] In 1987, U.S. President Ronald Reagan capitalized on the sentiments of the West Berliners as well as the freedom-starved East Berliners to demand that Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev "tear down" the Berlin Wall.[28] During the 2008 presidential elections, candidate Barack Obama capitalized on the sentiments of many American voters frustrated predominantly by the recent economic downturn and the continuing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. His simple messages of "Hope", "Change", and "Yes We Can" were adopted quickly and chanted by his supporters during his political rallies.[29]

Historical context and events may also encourage unruly behavior. Such examples include the:

- 1968 Columbia, SC Civil Rights Protest;

- 1992 London Poll Tax Protest; and

- 1992 L.A. Riots (sparked by the acquittal of police officers involved in the assault of Rodney King).[30]

In order to capitalize fully upon historical context, it is essential to conduct a thorough audience analysis to understand the desires, fears, concerns, and biases of the target crowd. This may be done through scientific studies, focus groups, and polls.[25]

Site selection

Where a crowd assembles also provides opportunities to manipulate thoughts, feelings, and emotions. Location, weather, lighting, sound, and even the shape of an arena all influence a crowd's willingness to participate.

Symbolic and tangible backdrops like the Brandenburg Gate, used by Presidents John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan, and Bill Clinton in 1963, 1987, and 1994, respectively, can evoke emotions before the crowd manipulator opens his or her mouth to speak.[31][32] George W. Bush's "Bullhorn Address" at Ground Zero following the 2001 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center is another example of how venue can amplify a message. In response to a rescue worker's shout, "I can't hear you", President Bush shouted back, "I can hear you! I can hear you! The rest of the world hears you! And the people – and the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon!" The crowd erupted in cheers and patriotic chants.[33]

Propaganda

The crowd manipulator and the propagandist may work together to achieve greater results than they would individually. According to Edward Bernays, the propagandist must prepare his target group to think about and anticipate a message before it is delivered. Messages themselves must be tested in advance since a message that is ineffective is worse than no message at all.[34] Social scientist Jacques Ellul called this sort of activity "pre-propaganda", and it is essential if the main message is to be effective. Ellul wrote in Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes:

Direct propaganda, aimed at modifying opinions and attitudes, must be preceded by propaganda that is sociological in character, slow, general, seeking to create a climate, an atmosphere of favorable preliminary attitudes. No direct propaganda can be effective without pre-propaganda, which, without direct or noticeable aggression, is limited to creating ambiguities, reducing prejudices, and spreading images, apparently without purpose. …

In Jacques Ellul's book, Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes, it states that sociological propaganda can be compared to plowing, direct propaganda to sowing; you cannot do the one without doing the other first.[35] Sociological propaganda is a phenomenon where a society seeks to integrate the maximum number of individuals into itself by unifying its members' behavior according to a pattern, spreading its style of life abroad, and thus imposing itself on other groups. Essentially sociological propaganda aims to increase conformity with the environment that is of a collective nature by developing compliance with or defense of the established order through long term penetration and progressive adaptation by using all social currents. The propaganda element is the way of life with which the individual is permeated and then the individual begins to express it in film, writing, or art without realizing it. This involuntary behavior creates an expansion of society through advertising, the movies, education, and magazines. "The entire group, consciously or not, expresses itself in this fashion; and to indicate, secondly that its influence aims much more at an entire style of life."[36] This type of propaganda is not deliberate but springs up spontaneously or unwittingly within a culture or nation. This propaganda reinforces the individual's way of life and represents this way of life as best. Sociological propaganda creates an indisputable criterion for the individual to make judgments of good and evil according to the order of the individual's way of life. Sociological propaganda does not result in action, however, it can prepare the ground for direct propaganda. From then on, the individual in the clutches of such sociological propaganda believes that those who live this way are on the side of the angels, and those who don't are bad.[37]

Bernays expedited this process by identifying and contracting those who most influence public opinion (key experts, celebrities, existing supporters, interlacing groups, etc.).

After the mind of the crowd is plowed and the seeds of propaganda are sown, a crowd manipulator may prepare to harvest his crop.[34]

Authority

The manipulator may be an orator, a group, a musician, an athlete, or some other person who moves a crowd to the point of agreement before he makes a specific call to action. Aristotle believed that the ethos, or credibility, of the manipulator contributes to his persuasiveness.

Prestige is a form of "domination exercised on our mind by an individual, a work, or an idea." The manipulator with great prestige paralyses the critical faculty of his crowd and commands respect and awe. Authority flows from prestige, which can be generated by "acquired prestige" (e.g. job title, uniform, judge's robe) and "personal prestige" (i.e. inner strength). Personal prestige is like that of the "tamer of a wild beast" who could easily devour him. Success is the most important factor affecting personal prestige. Le Bon wrote, "From the minute prestige is called into question, it ceases to be prestige." Thus, it would behoove the manipulator to prevent this discussion and to maintain a distance from the crowd lest his faults undermine his prestige.[38]

Delivery

The manipulator's ability to sway a crowd depends especially on his or her visual, vocal, and verbal delivery. Winston Churchill and Adolf Hitler made personal commitments to become master rhetoricians.

Churchill

At 22, Winston Churchill documented his conclusions about speaking to crowds. He titled it "The Scaffolding of Rhetoric" and it outlined what he believed to be the essentials of any effective speech. Among these essentials are:

- "Correctness of diction", or proper word choice to convey the exact meaning of the orator;

- "Rhythm", or a speech's sound appeal through "long, rolling and sonorous" sentences;

- "Accumulation of argument", or the orator's "rapid succession of waves of sound and vivid pictures" to bring the crowd to a thundering ascent;

- "Analogy", or the linking of the unknown to the familiar; and

- "Wild extravagance", or the use of expressions, however extreme, which embody the feelings of the orator and his audience.[39]

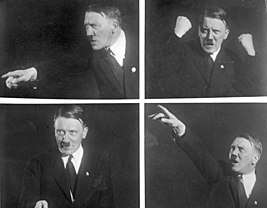

Hitler

Adolf Hitler believed he could apply the lessons of propaganda he learned painfully from the Allies during World War I and apply those lessons to benefit Germany thereafter. The following points offer helpful insight into his thinking behind his on-stage performances:

- Appeal to the masses: "[Propaganda] must be addressed always and exclusively to the masses", rather than the "scientifically trained intelligentsia."

- Target the emotions: "[Propaganda] must be aimed at the emotions and only to a very limited degree at the so-called intellect."

- Keep your message simple: "It is a mistake to make propaganda many-sided…The receptivity of the great masses is very limited, their intelligence is small, but their power of forgetting is enormous."

- Prepare your audience for the worst-case scenario: "[Prepare] the individual soldier for the terrors of war, and thus [help] to preserve him from disappointments. After this, the most terrible weapon that was used against him seemed only to confirm what his propagandists had told him; it likewise reinforced his faith in the truth of his government's assertions, while on the other hand it increased his rage and hatred against the vile enemy."

- Make no half statements: "…emphasize the one right which it has set out to argue for. Its task is not to make an objective study of the truth, in so far as it favors the enemy, and then set it before the masses with academic fairness; its task is to serve our own right, always and unflinchingly."

- Repeat your message constantly: "[Propagandist technique] must confine itself to a few points and repeat them over and over. Here, as so often in this world, persistence is the first and most important requirement for success."[40][41] (Gustave Le Bon believed that messages that are affirmed and repeated are often perceived as truth and spread by means of contagion. "Man, like animals, has a natural tendency to imitation. Imitation is a necessity for him, provided always that the imitation is quite easy", wrote Le Bon.[42] In his 1881 essay "L'Homme et Societes", he wrote "It is by examples not by arguments that crowds are guided." He stressed that in order to influence, one must not be too far removed his audience nor his example unattainable by them. If it is, his influence will be nil.[43]

The Nazi Party in Germany used propaganda to develop a cult of personality around Hitler. Historians such as Ian Kershaw emphasise the psychological impact of Hitler's skill as an orator.[44] Neil Kressel reports, "Overwhelmingly ... Germans speak with mystification of Hitler's 'hypnotic' appeal".[45] Roger Gill states: "His moving speeches captured the minds and hearts of a vast number of the German people: he virtually hypnotized his audiences".[46] Hitler was especially effective when he could absorb the feedback from a live audience, and listeners would also be caught up in the mounting enthusiasm.[47] He looked for signs of fanatic devotion, stating that his ideas would then remain "like words received under an hypnotic influence."[48][49]

Applications

Politics

The political process provides ample opportunity to utilize crowd-manipulation techniques to foster support for candidates and policy. From campaign rallies to town-hall debates to declarations of war, statesmen have historically used crowd manipulation to convey their messages. Public opinion polls, such as those conducted by the Pew Research Center and www.RealClearPolitics.com provide statesmen and aspiring statesmen with approval ratings, and wedge issues.

Business

Ever since the advent of mass production, businesses and corporations have used crowd manipulation to sell their products. Advertising serves as propaganda to prepare a future crowd to absorb and accept a particular message. Edward Bernays believed that particular advertisements are more effective if they create an environment which encourages the purchase of certain products. Instead of marketing the features of a piano, sell prospective customers the idea of a music room.[50]

The entertainment industry makes exceptional use of crowd manipulation to excite fans and boost ticket sales. Not only does it promote assembly through the mass media, it also uses rhetorical techniques to engage crowds, thereby enhancing their experience. At Penn State University-University Park, for example, PSU Athletics uses the Nittany Lion mascot to ignite crowds of more than 100,000 students, alumni, and other visitors to Beaver Stadium. Among the techniques used are cues for one side of the stadium to chant "We are..." while the other side responds, "Penn State!" These and other chants make Beaver Stadium a formidable venue for visiting teams who struggle to call their plays because of the noise.[51] World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE), formerly the World Wrestling Federation (WWF) employs crowd manipulation techniques to excite its crowds as well. It makes particular use of the polarizing personalities and prestige of its wrestlers to draw out the emotions of its audiences. The practice is similar to that of the ancient Roman gladiators, whose lives depended upon their ability to not only fight but also to win crowds.[52] High levels of enthusiasm are maintained using lights, sounds, images, and crowd participation. According to Hulk Hogan in his autobiography, My Life Outside the Ring, "You didn't have to be a great wrestler, you just had to draw the crowd into the match. You had to be totally aware, and really in the moment, and paying attention to the mood of the crowd."[53]

Flash mobs

A flash mob is a gathering of individuals, usually organized in advance through electronic means, that performs a specific, usually peculiar action and then disperses. These actions are often bizarre or comical—as in a massive pillow fight, ad-hoc musical, or synchronized dance. Bystanders are usually left in awe and/or shock.

The concept of a flash mob is relatively new when compared to traditional forms of crowd manipulation. Bill Wasik, senior editor of Harper's Magazine, is credited with the concept. He organized his first flash mob in a Macy's department store in 2003.[54] The use of flash mobs as a tool of political warfare may take the form of a massive walkout during a political speech, the disruption of political rally, or even as a means to reorganize a crowd after it has been dispersed by crowd control. A first glance, a flash mob may appear to be the spontaneous undoing of crowd manipulation (i.e. the turning of a crowd against its manipulator). On September 8, 2009, for example, choreographer Michael Gracey organized—with the help of cell phones and approximately twenty instructors—a 20,000+-person flash mob to surprise Oprah Winfrey during her 24th Season Kick-Off event. Following Oprah's introduction, The Black Eyed Peas performed their musical hit "I Gotta Feeling". As the song progressed, the synchronized dance began with a single, female dancer up front and spread from person to person until the entire crowd became involved. A surprised and elated Oprah found that there was another crowd manipulator besides her and her musical guests at work.[55] Gracey and others have been able to organize and manipulate such large crowds with the help of electronic devices and social networks.[55] But one does not need to be a professional choreographer to conduct such an operation. On February 13, 2009, for example, a 22-year-old Facebook user organized a flash mob which temporarily shut down London's Liverpool Street station.[56]

See also

- Brainwashing

- Collective behavior

- Collective narcissism

- Deception

- Demagogue

- Emotional contagion

- Focus group

- Gaslighting

- Group emotion

- Group think

- Oratory

- Perception management

- Persuasion

- Political warfare

- Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes

- Public diplomacy

- Psychological manipulation

- Psychological warfare

- Social engineering

- Social influence

References

- Adam Curtis (2002). The Century of the Self. British Broadcasting Cooperation (documentary). United Kingdom: BBC4.

- Edward L. Bernays and Mark Crispin Miller, Propaganda (Brooklyn, NY: Ig Publishing, 2004): 52.

- Jacques Ellul, Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1965): 15.

- Gustave Le Bon, The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind, Kindle Edition, Book I, Chapter 1 (Ego Books, 2008).

- John M. Kenny; Clark McPhail; et al. (2001). "Crowd Behavior, Crowd Control, and the Use of Non-Lethal Weapons". The Institute for Non-Lethal Defense Technologies, The Pennsylvania State University: 4–11. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Waller, Michael (2006). ""The American Way of Propaganda", White Paper No. 1, Version 2.4". Institute of World Politics. 4.

- Nye Jr., Joseph S. (2005). Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. Cambridge, MA: PublicAffairs.

- Aristotle, The Art of Rhetoric, translated with an introduction by H.C. Lawson-Tencred (New York, NY: Penguin Group, 2004): 1–13.

- Cheryl Glean (1997). Rhetoric Retold: Regendering the Tradition from Antiquity through the Reniassance. Illinois: SIU Press. pp. 33, 60.

- "manipulate". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. 2010. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- Le Bon, Book I, Chapter 1.

- Bernays, 109.

- Morton C. Blackwell, "People, Parties, and Power" Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, adapted from a speech to the Council for National Policy on February 10, 1990.

- "crowd". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. 2010. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- G. A. Tawney (October 15, 1905). "The Nature of Crowds". Psychological Bulletin. 2 (10): 332. doi:10.1037/h0072490.

- Kenny, et al., 13.

- John Drury; Paul Hutchinson; Clifford Stout (2001). "'Hooligans' abroad? Inter-Group Dynamics, Social Identity and Participation in Collective 'Disorder' at the 1998 World Cup Finals" (PDF). British Journal of Social Psychology. Great Britain: The British Psychological Society. 40 (3): 359–360. doi:10.1348/014466601164876. PMID 11593939.

- Clifford Stott (2009). "Crowd Psychology & Public Order Policing: An Overview of Scientific Theory and Evidence" (PDF). Liverpool School of Psychology, University of Liverpool. p. 4.

- Kenny, et al., 12.

- Stott, 12.

- Kenny, 12–20.

- Drury, J.; Reicher, S. & Stott, C. (2003). "Transforming the boundaries of collective identity: From the 'local' anti-road campaign to 'global' resistance?" (PDF). Social Movement Studies. 2 (2): 191–212. doi:10.1080/1474283032000139779.

- Stott.

- Waller, 1-4.

- Curtis.

- Paul Johnson, Modern Times: The World from the Twenties to the Nineties (New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 2001): 11–44; 231–2; 435, 489, 495–543, 582, 614, 632, 685, 757, 768.

- Wilson P. Dizard, Jr., Inventing Public Diplomacy: The Story of the U.S. Information Agency (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2004): 204.

- Smith-Davies Publishing, Speeches that Changed the World (London: Smith-Davies Publishing Ltd, 2005): 197–201.

- David E. Campbell, "Public Opinion and the 2008 Presidential Election" in Janet M. Box-Steffensmeier and Steven E. Schier, The American Elections of 2008 (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2009): 99–116.

- Kenny, et al.

- John Poreba (2010). "Speeches at the Brandenburg Gate: Public Diplomacy Through Political Oratory". StrategicDefense.net. Archived from the original on 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2010-09-12.

- Melissa Eddy, "Obama to speak near Berlin's Brandenburg Gate". Associated Press, July 20, 2008.

- American Rhetoric. "George W. Bush, Bullhorn Address to Ground Zero Rescue Workers". American Rhetoric.

- Bernays, 52.

- Ellul, 15.

- Ellul, Jacques (1973). Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes, p. 62.Trans. Konrad Kellen & Jean Lerner. Vintage Books, New York. ISBN 978-0-394-71874-3.

- Ellul, Jacques (1973). Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes, p. 65.Trans. Konrad Kellen & Jean Lerner. Vintage Books, New York. ISBN 978-0-394-71874-3.

- Le Bon, Book II, Chapter 3.

- Winston S. Churchill, "The Scaffolding of Rhetoric", in Randolph S. Churchill, Companion Volume 1, pt. 2, to Youth: 1874-1900, vol. 1 of the Official Biography of Winston Spencer Churchill (London: Heinmann, 1967): 816–21.

- Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, trans. Ralph Manheim (Mariner Books, 1998): 176–186.

- John Poreba (2010). "Tongue of Fury, Tongue of Fire: Oratory in the Rise of Hitler and Churchill". StrategicDefense.net. Archived from the original on 2016-08-21. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- Le Bon, Book II, Chapter 4.

- Gustave Le Bon, "L'Homme et Societes", vol. II. (1881): 116."

- Ian Kershaw, Hitler: A Biography (2008) pp 105-5.

- Neil Jeffrey Kressel (2013). Mass Hate: The Global Rise of Genocide and Terror. Springer. p. 141. ISBN 9781489960849.

- Roger Gill (2006). Theory and Practice of Leadership. SAGE. p. 259. ISBN 9781446228777.

- Carl J. Couch (2017). Information Technologies and Social Orders. Taylor & Francis. p. 213. ISBN 9781351295185.

- F.W. Lambertson, "Hitler, the orator: A study in mob psychology." Quarterly Journal of Speech 28#2 (1942): 123-131. online

- Yaniv Levyatan, "Harold D. Lasswell's analysis of Hitler's speeches." Media History 15#1 (2009): 55-69.

- Bernays, 19-20.

- J. Douglas Toma, Football U.: Spectator Sports in the Life of the American University (University of Michigan Press, 2003): 51-2.

- Rachael Hanel, Gladiators (Mankato, MN: The Creative Company, 2007): 24.

- Hulk Hogan and Mark Dagostino, My Life Outside the Ring (New York, NY: Macmillan, 2009): 119-120.

- Anjali Athavaley (April 15, 2008). "Students Unleash A Pillow Fight On Manhattan". Wall Street Journal.

- "Oprah's Kickoff Party Flash Mob Dance (VIDEO)". The Huffington Post. September 11, 2009. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- "Facebook flashmob shuts down station". www.CNN.com. February 19, 2009.

Further reading

- Alinsky, Saul. Rules for Radicals: A Practical Primer for Realistic Radicals. Vintage Books, 1989.

- Bernays, Edward L., and Mark Crispin Miller. Propaganda. Brooklyn, NY: Ig Publishing, 2004.

- Curtis, Adam. "The Century of the Self" (documentary). British Broadcasting Cooperation, UK, 2002.

- Ellul, Jacques. Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes. Trans. Konrad Kellen & Jean Lerner. New York: Knopf, 1965. New York: Random House/ Vintage 1973

- Humes, James C. The Sir Winston Method: The Five Secrets of Speaking the Language of Leadership. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, 1991.

- Johnson, Paul. Modern Times: The World from the Twenties to the Nineties. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 2001.

- Lasswell, Harold. Propaganda Technique in World War I. Cambridge, MA: The M.I.T. Press, 1971.

- Smith Jr., Paul A. On Political War. Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 1989.