Kingdom of Gwynedd

The Kingdom of Gwynedd (Medieval Latin: Venedotia or Norwallia; Middle Welsh: Guynet[4]) was a Roman Empire successor state that emerged in sub-Roman Britain in the 5th century during the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain.

Teyrnas Gwynedd | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5th century–1216 | |||||||||

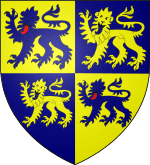

Traditional Banner of the Aberffraw House of Gwynedd | |||||||||

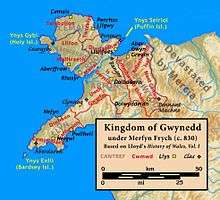

Medieval kingdoms of Wales. | |||||||||

| Capital | Chester (?) Deganwy (6th century) Llanfaes (9th century) Aberffraw Rhuddlan (11th century) Abergwyngregyn | ||||||||

| Common languages | Welsh,[nb 1] Latin[nb 2] | ||||||||

| Religion | Welsh paganism, Celtic Christianity | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

• 450–460 | Cunedda | ||||||||

• 520–547 | Maelgwn Gwynedd | ||||||||

• 625–634 | Cadwallon ap Cadfan | ||||||||

• 1081–1137 | Gruffudd ap Cynan | ||||||||

• 1137–1170 | Owain Gwynedd | ||||||||

• 1195–1240 | Llywelyn the Great | ||||||||

• 1253–1282 | Llywelyn ap Gruffudd | ||||||||

• 1282–1283 | Dafydd ap Gruffydd | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||

• Established | 5th century | ||||||||

• Declaration of the Principality of Wales | 1216 | ||||||||

| Currency | ceiniog cyfreith ceiniog cwta | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

^ In Latin, Gwynedd was often referred to in official medieval charters and acts of the 13th century as Principatus Norwallia (Principality of North Wales). | |||||||||

Based in northwest Wales, the rulers of Gwynedd repeatedly rose to dominance and were acclaimed as "King of the Britons" before losing their power in civil wars or invasions. The kingdom of Gruffydd ap Llywelyn—the King of Wales from 1055 to 1063—was shattered by a Saxon invasion in 1063 just prior to the Norman invasion of Wales, but the House of Aberffraw restored by Gruffudd ap Cynan slowly recovered and Llywelyn the Great of Gwynedd was able to proclaim the Principality of Wales at the Aberdyfi gathering of Welsh princes in 1216. In 1277, the Treaty of Aberconwy granted peace between the two but would also guarantee that Welsh self-rule would end upon Llewelyn's death, and so it represented the completion of the first stage of the conquest of Wales by Edward I.[5]

Welsh tradition credited the founding of Gwynedd to the Brittonic polity of Gododdin (Old Welsh Guotodin, earlier Brittonic form Votadini) from Lothian invading the lands of the Brittonic polities of the Deceangli, Ordovices, and Gangani in the 5th century.[6] The sons of their leader, Cunedda, were said to have possessed the land between the rivers Dee and Teifi.[7] The true borders of the realm varied over time, but Gwynedd proper was generally thought to comprise the cantrefs of Aberffraw, Cemais, and Cantref Rhosyr on Anglesey and Arllechwedd, Arfon, Dunoding, Dyffryn Clwyd, Llŷn, Rhos, Rhufoniog, and Tegeingl at the mountainous mainland region of Snowdonia opposite.

Etymology

The name Gwynedd is believed to be an early borrowing from Irish (reflective of Irish settlement in the area in antiquity), either cognate with the Old Irish ethnic name Féni, "Irish People", from Primitive Irish *weidh-n- "Forest People"/"Wild People" (from Proto-Indo-European *weydh- "wood, wilderness"), or (alternately) Old Irish fían "war band", from Proto-Irish *wēnā (from Proto-Indo-European *weyH1- "chase, pursue, suppress").[8][9][10][11]

The 5th-century Cantiorix Inscription now in Penmachno church seems to be the earliest record of the name.[6] It is in memory of a man named Cantiorix, and the Latin inscription is Cantiorix hic iacit/Venedotis cives fuit/consobrinos Magli magistrati: "Cantiorix lies here. He was a citizen of Gwynedd and a cousin of Maglos the magistrate".[6] The use of terms such as "citizen" and "magistrate" may be cited as evidence that Romano-British culture and institutions continued in Gwynedd long after the legions had withdrawn.[6]

History

Gwynedd in the Early Middle Ages

Cunedda and his sons

Ptolemy marks the Llŷn Peninsula as the "Promontory of the Gangani",[12] which is also a name he recorded in Ireland. In the late and post-Roman eras, Irish from Leinster[6] may have arrived in Anglesey and elsewhere in northwest Wales, with the name Llŷn derived from Laigin, an Old Irish form that means "of Leinster".

The region became known as Venedotia in Latin. The name was initially attributed to a specific Irish colony on Anglesey, but broadened to refer to Irish settlers as a whole in North Wales by the 5th century.[13][14] According to 9th century monk and chronicler Nennius, North Wales was left defenseless by the Roman withdrawal and subject to increasing raids by marauders from the Isle of Man and Ireland, a situation which led Cunedda, his sons and their entourage, to migrate in the mid-5th century from Manaw Gododdin (now Clackmannanshire, Scotland) to settle and defend North Wales against the raiders and bring the region within Romano-British control.[6] According to traditional pedigrees, Cunedda's grandfather was Padarn Beisrudd, Paternus of the red cloak, "an epithet which suggests that he wore the cloak of a Roman officer", according to Davies.[6] Nennius recounts how Cunedda brought order to North Wales and after his death Gwynedd was divided among his sons: Dynod was awarded Dunoding, another son Ceredig received Ceredigion, and so forth.[6] However, this overly neat origin myth has been met with skepticism:

Early Welsh literature contains a wealth of stories seeking to explain place-names, and doubtless the story is propaganda aimed at justifying the right of Cunedda and his descendants to territories beyond the borders of the original Kingdom of Gwynedd. That kingdom probably consisted of the two banks of the Menai Straits and the coast over towards the estuary of the river Conwy, the foundations upon which Cunedda's descendants created a more extensive realm.

— John Davies, History of Wales, p. 51,[6]

Undoubtedly, a Brittonic leader of substance established himself in North Wales, and he and his descendants defeated any remaining Irish presence, incorporated the settlements into their domain and reoriented the whole of Gwynedd into a Romano-British and "Welsh" outlook.

The Welsh of Gwynedd remained conscious of their Romano-British heritage, and an affinity with Rome survived long after the Empire retreated from Britain, particularly with the use of Latin in writing and sustaining the Christian religion.[6][15] The Welsh ruling classes continued to emphasize Roman ancestors within their pedigrees as a way to link their rule with the old imperial Roman order, suggesting stability and continuity with that old order.[6][15] According to Professor John Davies, "[T]here is a determinedly Brythonic, and indeed Roman, air to early Gwynedd."[6] So palpable was the Roman heritage felt that Professor Bryan Ward-Perkins of Trinity College, Oxford, wrote "It took until 1282, when Edward I conquered Gwynedd, for the last part of Roman Britain to fall [and] a strong case can be made for Gwynedd as the very last part of the entire Roman Empire, east and west, to fall to the barbarians."[15][16] Nevertheless, there was generally quick abandonment of Roman political, social, and ecclesiastical practices and institutions within Gwynedd and elsewhere in Wales.[15] Roman knowledge was lost as the Romano-Britons shifted towards a streamlined militaristic near-tribal society that no longer included the use of coinage and other complex industries dependent on a money economy, architectural techniques using brick and mortar, and even more basic knowledge such as the use of the wheel in pottery production.[15] Ward-Perkins suggests the Welsh had to abandon those Roman ways that proved insufficient, or indeed superfluous, to meet the challenge of survival they faced: "Militarized tribal societies, despite their political fragmentation and internecine strife, seem to have offered better protection against Germanic invasion than exclusive dependence on a professional Roman army (that in the troubled years of the fifth century was all too prone to melt away or mutiny)."[15]

Reverting to a more militaristic tribal society allowed the Welsh of Gwynedd to concentrate on those martial skills necessary for their very survival,[15] and the Romano-Britons of western Britain did offer stiffer and an ultimately successful resistance.[15] The region of Venedotia, however, had been under Roman military administration and included established Irish Gaelic settlements, and the civilian element there was less extensive, perhaps facilitating technological loss.

In the post-Roman period, the earliest rulers of Wales and Gwynedd may have exerted authority over regions no larger than the cantrefi (hundred) described in Welsh law codified centuries later, with their size somewhat comparable in size to the Irish tuath.[6] These early petty kings or princelings (Lloyd uses the term chieftain) adopted the title rhi in Welsh (akin to the Irish Gaelic rí), later replaced by brenin, a title used to "denote a less archaic form of kingship," according to Professor John Davies.[6] Genealogical lists compiled around 960 bear out that a number of these early rulers claimed degrees of association with the old Roman order, but do not appear in the official royal lineages.[6] "It may be assumed that the stronger kings annexed the territories of their weaker neighbors and that the lineages of the victors are the only lineages to have survived," according to Davies.[6] Smaller and weaker chieftains coalesced around more powerful princelings, sometimes through voluntary vassalage or inheritance, though at other times through conquest, and the lesser princelings coalesced around still greater princelings, until a regional prince could claim authority over the whole of north Wales from the River Dyfi in the south to the Dee in the east, and incorporating Anglesey.[6]

Other evidence supports Nennius's claim that a leader came to north Wales and brought the region a measure of stability, although an Irish Gaelic element remained until the mid-5th century. Cunedda's heir Einion Yrth ap Cunedda defeated the remaining Gaelic Irish on Anglesey by 470, while his son, Cadwallon Lawhir ap Einion, appears to have consolidated the realm during the time of relative peace following the Battle of Badon, where the Anglo-Saxons were soundly defeated. During that peace he established a mighty kingdom. After Cadwallon, Gwynedd appears to have held a pre-eminent position amongst the petty Cambrian states in the post-Roman period. The great-grandson of Cunedda, Maelgwn Hir "Maelgwn the Tall", was one of the most famous (or infamous) leaders in Welsh history. There are several legends about his life concerning miracles performed either by him or in his presence. He is attributed in some old stories as hosting the first Eisteddfod and he is one of five Celtic British kings castigated for their sins by the contemporary Christian writer Gildas (who referred to him as Maglocunus, meaning 'Prince-Hound' in Brittonic) in De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae. Maelgwn was curiously described as "the dragon of the island" by Gildas which was possibly a title, but explicitly as the most powerful of the five named British kings. "[Y]ou the last I write of but the first and greatest in evil, more than many in ability but also in malice, more generous in giving but also more liberal in sin, strong in war but stronger to destroy your soul."

Maelgwn eventually died from the plague in 547, leaving a succession crisis in his wake. His son-in-law, Elidyr Mwynfawr of the Kingdom of Strathclyde, claimed the throne and invaded Gwynedd to displace Maelgwn's son, Rhun Hir ap Maelgwn. Elidyr was killed in the attempt, but his death was then avenged by his relatives, who ravaged the coast of Arfon. Rhun counter-attacked and exacted the same penalty on the lands of his foes in what is now central Scotland. The long distances these armies travelled suggests they were moving across the Irish Sea, but, because almost all of what is now northern England was at this point (c. 550) under Brittonic rule, it is possible that his army marched to Strathclyde overland. Rhun returned to Gwynedd, and the rest of his reign was far less eventful. He was succeeded by his son, Beli ap Rhun in c. 586.

On the accession of Beli's son Iago ap Beli in c. 599, the situation in Britain had deteriorated significantly. Most of northern England had been overrun by the invading Angles of Deira and Bernicia, who were in the process of forming the Kingdom of Northumbria. In a rare show of common interest, it appears that Gwynedd and the neighbouring Kingdom of Powys acted in concert to rebuff the Anglian advance but were defeated at the Battle of Chester in 613. Following this catastrophe, the approximate borders of northern Wales were set with the city of Caerlleon (now called Chester) and the surrounding Cheshire Plain falling under the control of the Anglo-Saxons.

Cadwallon ap Cadfan

The Battle of Chester would not end the ability of the Welsh to seriously threaten the Anglo-Saxon polities. Among the most powerful of the early kings was Cadwallon ap Cadfan (c. 624 – 634), grandson of Iago ap Beli. He became engaged in an initially disastrous campaign against Northumbria where following a series of epic defeats he was confined first to Anglesey and then just to Puffin Island before being forced into exile across the Irish Sea to Dublin – a place which would come to host many royal refugees from Gwynedd. All must have seemed lost but Cadwallon raised an enormous army and after a brief time in Guernsey he invaded Dumnonia, relieved the West Welsh who were suffering a Mercian invasion and forced the pagan Penda of Mercia into an alliance against Northumbria. With new vigour Cadwallon returned to his Northumbrian foes, devastated their armies and slaughtered a series of their kings. In this furious campaign his armies devastated Northumbria, captured and sacked York in 633 and briefly controlled the kingdom. At this time, according to Bede, many Northumbrians were slaughtered, “with savage cruelty”, by Cadwallon.[17]

[H]e neither spared the female sex, nor the innocent age of children, but with savage cruelty put them to tormenting deaths, ravaging all their country for a long time, and resolving to cut off all the race of the English within the borders of Britain.

However, these tumultuous events would come to be short-lived, for he died in battle in 634 close to Hadrian's Wall. On account of these deeds, he and his son Cadwaladr appear to have been considered the last two High Kings of Britain. Cadwaladr presided over a period of consolidation and devoted much time to the Church, earning the title "Bendigaid" for "Blessed".

Rhodri the Great and Aberffraw primacy

During the later 9th and 10th centuries, the coastal areas of Gwynedd, particularly Anglesey, were coming under increasing attack by the Vikings. These raids no doubt had a seriously debilitating effect on the country but fortunately for Gwynedd, the victims of the Vikings were not confined to Wales. The House of Cunedda – as the direct descendants of Cunedda are known – eventually expired in the male line in 825 upon the death of Hywel ap Rhodri Molwynog and, as John Edward Lloyd put it, "a stranger possessed the throne of Gwynedd."[18]

This "stranger" who became the next King of Gwynedd was Merfyn "Frych" (Merfyn "the Freckled"). When, however, Merfyn Frych's pedigree is examined – and to the Welsh pedigree meant everything – he seems not a stranger but a direct descendant of the ancient ruling line. Some sources state he was the son of Erthil, a prince of the Hen Ogledd, while others suggest he was the son of Gwriad, the contemporaneous king of the Isle of Man. All sources agree that he was the son of Esyllt, heiress and niece of the aforementioned Hywel ap Rhodri Molwynog, last of the House of Cunedda, and that his male line went back to the Hen Ogledd to Llywarch Hen, a first cousin of Urien and thus a direct descendant of Coel Hen.[19] Thus the House of Cunedda and the new House of Aberffraw, as Merfyn's descendants came to be known, shared Coel Hen as a common ancestor, although the House of Cunedda traced their line through Gwawl his daughter and wife of Cunedda.

Merfyn married Nest ferch Cadell, the sister of Cyngen ap Cadell, the King of Powys, and founded the house of Aberffraw, named after his principal court on Anglesey. No written records are preserved from the Britons of southern Scotland and northern England and it is very likely that Merfyn Frych brought many of these legends as well as his pedigree with him when he came to north Wales. It appears most probable that it was at Merfyn's court that all the lore of the north was collected and written down during his reign and that of his son.[19]

Rhodri the Great (844–878), son of Merfyn Frych and Nest ferch Cadell, was able to add Powys to his realm after its king (his maternal uncle) died on pilgrimage to Rome in 855. Later, he married Angharad ferch Meurig, the sister of King Gwgon of Seisyllwg. When Gwgon drowned without heir in 872, Rhodri became steward over the kingdom and able to install his son, Cadell ap Rhodri, as a subject king. Thus, he became the first ruler since the days of Cunedda to control the greater part of Wales.

When Rhodri died in 878 the relative unity of Wales ended and it was once again divided into its component parts each ruled by one of his sons. Rhodri's eldest son Anarawd ap Rhodri inherited Gwynedd and would firmly establish the princely House of Aberffraw that would come to rule Gwynedd with but a few interruptions until 1283.

From the successes of Rhodri and the seniority of Anarawd among his sons the Aberffraw family claimed primacy over all other Welsh lords including the powerful kings of Powys and Deheubarth.[20][21] In The History of Gruffudd ap Cynan, written in the late 12th century, the family asserted its rights as the senior line of descendants from Rhodri the Great who had conquered most of Wales during his lifetime.[20] Gruffudd ap Cynan's biography was first written in Latin and intended for a wider audience outside Wales.[20] The significance of this claim was that the Aberffraw family owed nothing to the English king for its position in Wales, and that they held authority in Wales "by absolute right through descent," wrote historian John Davies.[20]

The House of Aberffraw was displaced in 942 by Hywel Dda, a King of Deheubarth from a junior line of descent from Rhodri Mawr. This occurred because Idwal Foel, the King of Gwynedd, was determined to cast off English overlordship and took up arms against the new English king, Edmund I. Idwal and his brother Elisedd were both killed in battle against Edmund's forces. By normal custom Idwal's crown should have passed to his sons, Ieuaf and Iago ab Idwal, but Hywel Dda intervened and sent Iago and Ieuaf into exile in Ireland and established himself as ruler over Gwynedd until his death in 950 when the House of Aberffraw was restored. Nonetheless, surviving manuscripts of Cyfraith Hywel recognize the importance of the lords of Aberffraw as overlords of Wales along with the rulers of Deheubarth.[22]

Between 986 and 1081 the throne of Gwynedd was often in contention with the rightful kings frequently displaced by rivals within and outside the realm. One of these, Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, originally from Powys, displaced the Aberffraw line from Gwynedd making himself ruler there, and by 1055 was able to make himself king of most of Wales. He became powerful enough to present a real menace to England and annexed some neighbouring parts after several victories over English armies. Eventually he was defeated by Harold Godwinson in 1063 and later killed by his own men in a deal to secure peace with England. Bleddyn ap Cynfyn and his brother Rhiwallon of the Mathrafal dynasty of Powys, Gruffudd's maternal half-brothers, came to terms with Harold and took over the rule of Gwynedd and Powys.

Shortly after the Norman conquest of England in 1066 the Normans began to exert pressure on the eastern border of Gwynedd. They were helped by internal strife following the killing of Bleddyn ap Cynfyn in 1075 by his second cousin Rhys ap Owain King of Deheubarth. Another relative of Bleddyn's Trahaearn seized the throne but was soon challenged by Gruffudd ap Cynan, the exiled grandson of Iago ab Idwal ap Meurig who had been living in the Norse–Gael stronghold of Dublin. In 1081 Trahaearn was killed by Gruffudd in battle and the ancient line of Rhodri Mawr was restored.

Gwynedd in the High Middle Ages

Gruffudd ap Cynan

The Aberffraw dynasty suffered various depositions by rivals in Deheubarth, Powys, and England in the 10th and 11th centuries. Gruffudd ap Cynan (c. 1055–1137), who grew up in exile in Norse–Gael Dublin, regained his inheritance following his victory at the Battle of Mynydd Carn in 1081 over his Mathrafal rivals then in control of Gwynedd.[23][24] However, Gruffudd's victory was short-lived as the Normans launched an invasion of Wales following the Saxon revolt in northern England, known as the Harrowing of the North.

Shortly after the Battle of Mynydd Carn in 1081, Gruffudd was lured into a trap with the promise of an alliance but seized by Hugh d'Avranches, Earl of Chester, in an ambush near Corwen.[23][24][25] Earl Hugh claimed the Perfeddwlad up to the River Clwyd (the commotes of Tegeingl and Rhufoniog; the modern counties of Denbighshire, Flintshire, and Wrexham) as part of Chester, and viewed the restoration of the Aberffraw family in Gwynedd as a threat to his own expansion into Wales.[24] The lands west of the Clwyd were intended for his cousin Robert of Rhuddlan, and their advance extended to the Llŷn Peninsula by 1090.[24] By 1094 almost the whole of Wales was occupied by Norman forces.[24] However, although they erected many castles, Norman control in most regions of Wales was tenuous at best.[24] Motivated by local anger over the "gratuitously cruel" invaders, and led by the historic ruling houses, Welsh control over the greater part of Wales was restored by 1100.[24]

In an effort to further consolidate his control over Gwynedd, Earl Hugh of Chester had Hervey le Breton elected as Bishop of Bangor in 1092, and consecrated by Thomas of Bayeux, Archbishop of York.[26] It was hoped that placing a prelate loyal to the Normans over the traditionally independent Welsh church in Gwynedd would help to pacify the local inhabitants, and Hervé recognized the primacy of the Archbishop of Canterbury over the episcopal see of Bangor, a recognition hitherto rejected by the Welsh church.

However, the Welsh parishioners remained hostile to Hervey's appointment, and the bishop was forced to carry a sword with him and rely on a contingent of Norman knights for his protection.[27][28] Additionally, Hervey routinely excommunicated parishioners who he perceived as challenging his spiritual and temporal authority.[27]

Illustration by T. Prytherch in 1900

Gruffudd escaped imprisonment in Chester, and slew Robert of Rhuddlan in a beachside battle at Deganwy on 3 July 1093.[25] Gruffudd recovered Gwynedd by 1095, and by 1098 Gruffudd allied with Cadwgan ap Bleddyn of the Mathrafal house of Powys, their traditional dynastic rivalry notwithstanding.[23][24] Gruffudd and Cadwgan led the Welsh resistance to the Norman occupation in north and mid Wales.[23][24] However, by 1098 Earl Hugh of Chester and Hugh of Montgomery, 2nd Earl of Shrewsbury advanced their army to the Menai Strait, with Gruffudd and Cadwgan regrouping on defensible Anglesey, where they planned to make retaliatory strikes from their island fortress.[23][24] Gruffudd hired a Norse fleet from a settlement in Ireland to patrol the Menai and prevent the Norman army from crossing; however, the Normans were able to pay off the fleet to instead ferry them to Môn.[23][24] Betrayed, Gruffudd and Cadwgan were forced to flee to Ireland in a skiff.[23][24]

The Normans landed on Anglesey, and their furious 'victory celebrations' which followed were exceptionally violent, with rape and carnage committed by the Norman army left unchecked.[23] The earl of Shrewsbury had an elderly priest mutilated, and made the church of Llandyfrydog a kennel for his dogs.[23]

During the 'celebrations' a Norse fleet led by Magnus Barefoot, King of Norway, appeared off the coast at Puffin Island, and in the battle that followed, known as the Battle of Anglesey Sound, Magnus shot dead the earl of Shrewsbury with an arrow to the eye.[23] The Norse left as suddenly and as mysteriously as they had arrived, leaving the Norman army weakened and demoralized.[23]

The Norman army retired to England, leaving a Welshman, Owain ab Edwin of Tegeingl, in command of a token force to control Ynys Môn and upper Gwynedd, and ultimately abandoning any colonization plans there.[23][29] Owain ap Edwin transferred his allegiance to Chester following the defeat of his ally Trahaearn ap Caradog in 1081, a move which earned him the epithet Bradwr "the Traitor" (Welsh: Owain Fradwr), among the Welsh.[29]

In late 1098 Gruffudd and Cadwgan landed in Wales and recovered Angelsey without much difficulty, with Hervé the Breton fleeing Bangor for safety in England. Over the course of the next three years, Gruffudd was able to recover upper Gwynedd to the Conwy, defeating Hugh, Earl of Chester.[23] In 1101, after Earl Hugh's death, Gruffudd and Cadwgan came to terms with England's new king, Henry I, who was consolidating his own authority and also eager to come to terms. In the negotiations which followed Henry I recognized Gruffudd's ancestral claims of Angelsey, Llŷn, Dunoding (Eifionydd and Ardudwy) and Arllechwedd, being the lands of upper Gwynedd to the Conwy which were already firmly in Gruffudd's control.[23] Cadwgan regained Ceredigion, and his share of the family inheritance in Powys, from the new earl of Shrewsbury, Robert of Bellême.[23]

With the settlement reached between Henry I and Gruffudd, and other Welsh lords, the dividing of Wales between Pura Wallia, the lands under Welsh control; and Marchia Wallie, Welsh lands under Norman control, came into existence.[30] Author and historian John Davies notes that the border shifted on occasion, "in one direction and in the other", but remained more or less stable for almost the next two hundred years.[30]

After generations of incessant warfare, Gruffudd began the reconstruction of Gwynedd, intent on bringing stability to his country.[24] According to Davies, Gruffudd sought to give his people the peace to "plant their crops in the full confidence that they would be able to harvest them".[24] Gruffudd consolidated royal authority in north Wales, and offered sanctuary to displaced Welsh from the Perfeddwlad, particularly from Rhos, at the time harassed by Richard, 2nd Earl of Chester.[31]

Alarmed by Gruffudd's growing influence and authority in north Wales, and on pretext that Gruffudd sheltered rebels from Rhos against Chester, Henry I launched a campaign against Gwynedd and Powys in 1116, which included a vanguard commanded by King Alexander I of Scotland.[23][24] While Owain ap Cadwgan of Ceredigion sought refuge in Gwynedd's mountains, Maredudd ap Bleddyn of Powys made peace with the English king as the Norman army advanced.[23] There were no battles or skirmishes fought in the face of the vast host brought into Wales; rather, Owain and Gruffudd entered into truce negotiations. Owain ap Cadwgan regained royal favor relatively easily. However, Gruffudd was forced to render homage and fealty and pay a heavy fine, though he lost no land or prestige.[31]

The invasion left a lasting impact on Gruffudd, who by 1116 was in his 60s and with failing eyesight.[23] For the remainder of his life, while Gruffudd continued to rule in Gwynedd, his sons Cadwallon, Owain, and Cadwaladr, would lead Gwynedd's army after 1120.[23] Gruffudd's policy, which his sons would execute and later rulers of Gwynedd adopted, was to recover Gwynedd's primacy without blatantly antagonizing the English crown.[23][31]

The Expansion of Gwynedd

In 1120 a minor border war between Llywarch ab Owain, lord of a commote in the Dyffryn Clwyd cantref, and Hywel ab Ithel, lord of Rhufoniog and Rhos, brought Powys and Chester into conflict in the Perfeddwlad.[31] Powys brought a force of 400 warriors to the aid of its ally Rhufoniog, while Chester sent Norman knights from Rhuddlan to the aid of Dyffryn Clwyd.[31] The bloody Battle of Maes Maen Cymro, fought a mile to the north-west of Ruthin, ended with Llywarch ab Owain slain and the defeat of Dyffryn Clwyd. However, it was a pyrrhic victory as the battle left Hywel ab Ithel mortally wounded.[31] The last of his line, when Hywel ab Ithel died six weeks later, he left Rhufoniog and Rhos bereft.[31] Powys, however, was not strong enough to garrison Rhufoniog and Rhos, nor was Chester able to exert influence inland from its coastal holdings of Rhuddlan and Degannwy.[31] With Rhufoniog and Rhos abandoned, Gruffudd annexed the cantrefs.[31]

On the death of Einion ap Cadwgan, lord of Meirionnydd, a quarrel engulfed his kinsmen on who should succeed him.[31] Meirionnydd was then a vassal cantref of Powys, and the family there a cadet of the Mathrafal house of Powys.[31] Gruffudd gave licence to his sons Cadwallon and Owain to press the opportunity the dynastic strife in Meirionnydd presented.[31] The brothers raided Meirionnydd with the Lord of Powys as important there as he was in the Perfeddwlad.[31] However it would not be until 1136 that the cantref was firmly within Gwynedd's control.[31] Perhaps because of their support of Earl Hugh of Chester, Gwynedd's rival, in 1124 Cadwallon slew the three rulers of Dyffryn Clwyd, his maternal uncles, bringing the cantref firmly under Gwynedd's vassalage that year.[31] And in 1125 Cadwallon slew the grandsons of Edwin ap Goronwy of Tegeingl, leaving Tegeingl bereft of lordship.[29] However, in 1132 while on campaign in the commote of Nanheudwy, near Llangollen, 'victorious' Cadwallon was defeated in battle and slain by an army from Powys.[31] The defeat checked Gwynedd's expansion for a time, "much to the relief of the men of Powys", wrote historian Sir John Edward Lloyd (J.E Lloyd).[31]

In 1136 a campaign against the Normans was launched from Gwynedd in revenge for the execution of Gwenllian ferch Gruffudd ap Cynan, the wife of the King of Deheubarth and the daughter of Gruffudd. When word reached Gwynedd of Gwenllian's death and the revolt in Gwent, Gruffudd's sons Owain and Cadwaladr invaded Norman controlled Ceredigion, taking Llanfihangle, Aberystwyth, and Llanbadarn.[32][33] Liberating Llanbadarn, one local chronicler hailed Owain and Cadwaladr both as "bold lions, virtuous, fearless and wise, who guard the churches and their indwellers, defenders of the poor [who] overcome their enemies, affording a safest retreat to all those who seek their protection".[32] The brothers restored the Welsh monks of Llanbadarn, who had been displaced by monks from Gloucester brought there by the Normans who had controlled Ceredigion.[32] By late September 1136 a vast Welsh host gathered in Ceredigion, which included the combined forces of Gwynedd, Deheubarth, and Powys, and met the Norman army at the Battle of Crug Mawr at Cardigan Castle.[32] The battle turned into a rout, and then into a resounding defeat of the Normans.[32]

When their father Gruffudd died in 1137, the brothers Owain and Cadwaladr were on a second campaign in Ceredigion, and took the castles of Ystrad Meurig, Lampeter (Stephen's Castle), and Castell Hywell (Humphries Castle)[32] Gruffudd ap Cynan left a more stable realm then had hitherto existed in Gwynedd for more than 100 years.[34] No foreign army was able to cross the Conwy into upper Gwynedd. The stability of Gruffudd's long reign allowed for Gwynedd's Welsh to plan for the future without fear that home and harvest would "go to the flames" from invaders.[34]

Settlements became more permanent, with buildings of stone replacing timber structures. Stone churches in particular were built across Gwynedd, with so many limewashed that "Gwynedd was bespangled with them as is the firmament with stars".[34] Gruffudd had built stone churches at his royal manors, and Lloyd suggests Gruffudd's example led to the rebuilding of churches with stone in Penmon, Aberdaron, and Towyn in the Norman fashion.[34]

Gruffudd promoted the primacy of the Episcopal See of Bangor in Gwynedd, and funded the building of Bangor Cathedral during the episcopate of David the Scot, Bishop of Bangor, between 1120–1139. Gruffudd's remains were interred in a tomb in the presbytery of Bangor Cathedral.[34]

Owain Gwynedd

Owain ap Gruffudd succeeded his father to the greater portion of Gwynedd in accordance with Welsh law, the Cyfraith Hywel, the Laws of Hywel; and became known as Owain Gwynedd to differentiate him from another Owain ap Gruffudd, the Mathrafal ruler of Powys, known as Owain Cyfeiliog.[35] Cadwaladr, Gruffudd's youngest son, inherited the commote of Aberffraw on Ynys Môn, and the recently conquered Meirionydd and northern Ceredigion--i.e., Ceredigion between the rivers Aeron and the Dyfi.[36]

By 1141 Cadwaladr and Madog ap Maredudd of Powys led a Welsh vanguard as an ally of the Earl of Chester in the Battle of Lincoln, and joined in the rout which made Stephen of England prisoner of Empress Matilda for a year.[37] Owain, however, did not participate in the battle, keeping the majority of Gwynedd's army at home.[37] Owain, of restrained and prudent temperament, may have judged that aiding in Stephen's capture would lead to the restoration of Matilda and a strong royal government in England, a government which would support Marcher lords—support hitherto lacking since Stephen's usurpation.

Owain and Cadwaladr came to blows in 1143 when Cadwaladr was implicated in the murder of King Anarawd ap Gruffudd of Deheubarth, Owain's ally and future son-in-law, on the eve of Anarawd's wedding to Owain's daughter.[38][39] Owain followed a diplomatic policy of binding other Welsh rulers to Gwynedd through dynastic marriages, and Cadwaladr's border dispute and murder of Anarawd threatened Owain's efforts and credibility.[33] As ruler of Gwynedd, Owain stripped Cadwaladr of his lands, with Owain's son Hywel dispatched to Ceredigion, where he burned Cadwaladr's castle at Aberystwyth.[38] Cadwaladr fled to Ireland and hired a Norse fleet from Dublin, bringing the fleet to Abermenai to compel Owain to reinstate him.[38] Taking advantage of the brotherly strife, and perhaps with the tacit understanding of Cadwaladr, the marcher lords mounted incursions into Wales.[39] Realizing the wider ramifications of the war before him, Owain and Cadwaladr came to terms and reconciled, with Cadwaladr restored to his lands.[38][39] Peace between the brothers held until 1147, when an unrecorded event occurred which led Owain's sons Hywel and Cynan to drive Cadwaladr out of Meirionydd and Ceredigon, with Cadwaladr retreating to Môn.[38] Again an accord was reached, with Cadwaladr retaining Aberffraw until a more serious breach occurred in 1153, when he was forced into exile in England, where his wife was the sister of Gilbert de Clare, 1st Earl of Hertford and the niece of Ranulf de Gernon, 4th Earl of Chester.[38][39]

In 1146 news reached Owain that his favoured eldest son and heir, Rhun ab Owain Gwynedd, died. Owain was overcome with grief, falling into a deep depression from which none could console him, until news reached him that Mold Castle in Tegeingl had fallen to Gwynedd, "[reminding Owain] that he had still a country for which to live," wrote historian Sir John Edward Lloyd.[40]

Between 1148 and 1151, Owain I of Gwynedd fought against Madog ap Maredudd of Powys, Owain's son-in-law, and against the Earl of Chester for control of Iâl, with Owain having secured Rhuddlan Castle and all of Tegeingl from Chester.[41] "By 1154 Owain had brought his men within sight of the red towers of the great city on the Dee", wrote Lloyd."[41]

Having spent three years consolidating his authority in the vast Angevin Empire, Henry II of England resolved on a strategy against Owain I of Gwynedd by 1157. By now, Owain's enemies had joined Henry II's camp, enemies such as his wayward brother Cadwaladr and in particular the support of Madog of Powys.[42] Henry II raised his feudal host and marched into Wales from Chester.[42] Owain positioned himself and his army at Dinas Basing (Basingwerk), barring the road to Rhuddlan, setting up a trap in which Henry II would send his army along the direct road on the coast, while he crossed through the woods to out-flank Owain. The King of Gwynedd anticipated this, and dispatched his sons Dafydd ab Owain Gwynedd and Cynan into the woods with an army, catching Henry II unaware.[42]

In the melee which followed Henry II might have been slain had not Roger de Clare, 2nd Earl of Hertford, rescued the king.[42] Henry II retreated and made his way back to his main army, by now slowly advancing towards Rhuddlan.[42] Not wishing to engage the Norman army directly, Owain repositioned himself first at St. Asaph, then further west, clearing the road for Henry II to enter into Rhuddlan "ingloriously".[42] Once in Rhuddlan Henry II received word that his naval expedition had failed, as instead of meeting Henry II at Degannwy or Rhuddlan, it had gone to plunder Anglesey.

In a later letter to the Byzantine emperor, Henry probably recalled these experiences when he wrote, "A people called Welsh, so bold and ferocious that, when unarmed, they do not fear to encounter an armed force, being ready to shed their blood in defence of their country, and to sacrifice their lives for renown."[43]

The naval expedition was led by Henry II's maternal uncle (Empress Matilda's half-brother), Henry FitzRoy; and when they landed on Môn, Henry FitzRoy had the churches of Llanbedr Goch and Llanfair Mathafarn Eithaf torched.[42] During the night the men of Môn gathered together, and the next morning fought and defeated the Norman army, with Henry FitzRoy falling under a shower of lances.[42] The defeat of his navy and his own military difficulties had convinced Henry II that he had "gone as far as was practical that year" in his effort to subject Owain, and the King offered terms.[42]

Owain I of Gwynedd, "ever prudent and sagacious", recognized that he needed time to further consolidate power, and agreed to the terms. Owain was to render homage and fealty to the King, and resign Tegeingl and Rhuddlan to Chester, and restore Cadwaladr to his possessions in Gwynedd.[42]

The death of Madog ap Meredudd of Powys in 1160 opened an opportunity for Owain I of Gwynedd to further press Gwynedd's influence at the expense of Powys.[44] However, Owain continued to further Gwynedd's expansion without rousing the English crown, maintaining his 'prudent policy' of Quieta non movere (don't move settled things), as Lloyd wrote.[44] It was a policy of outward conciliation, while masking his own consolidation of authority.[44] To further demonstrate his good-will, in 1160 Owain handed over to the English crown the fugitive Einion Clud.[44] By 1162 Owain was in possession of the Powys cantref of Cyfeiliog, and its castle, Tafolwern; and ravaged another Powys cantref, Arwystli, slaying its lord, Hywel ab Ieuaf.[44] Owain's strategy was in sharp contrast to Rhys ap Gruffudd, King of Deheubarth, who in 1162 rose in open revolt against the Normans in south Wales, drawing Henry II back to England from the continent.

In 1163 Henry II quarrelled with Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, causing growing divisions between the king's supporters and the archbishop's supporters. With discontent mounting in England, Owain of Gwynedd joined with Rhys ap Gruffudd of Deheubarth in a second grand Welsh revolt against Henry II.[44][45] England's king, who only the prior year had pardoned Rhys ap Gruffudd for his 1162 revolt, assembled a vast host against the allied Welsh, with troops drawn from all over the Angevin empire assembling in Shrewsbury, and with the Norse of Dublin paid to harass the Welsh coast.[44] While his army gathered on the Welsh frontier, Henry II left for the continent to negotiate a truce with France and Flanders to not disturb his peace while campaigning in Wales.[46]

However, when Henry II returned to England he found that the war had already begun, with Owain's son Dafydd raiding Angevin positions in Tegeingl, exposing the castles of Rhuddlan and Basingwerk to "serious dangers", wrote Lloyd.[46] Henry II rushed to north Wales for a few days to shore up defences there, before returning to his main army now gathering in Oswestery.[46]

The vast host gathered before the allied Welsh principalities represented the largest army yet assembled for their conquest, a circumstance which further drew the Welsh allies into a closer confederacy, wrote Lloyd.[46] With Owain I of Gwynedd the overall battle commander, and with his brother Cadwaladr as his second, Owain assembled the Welsh host at Corwen in the vale of Edeyrion where he could best resist Henry II's advance.[46]

The Angevin army advanced from Oswestry into Wales crossing the mountains towards Mur Castell, and found itself in the thick forest of the Ceiriog Valley where they were forced into a narrow thin line.[46] Owain I had positioned a band of skirmishers in the thick woods overlooking the pass, which harassed the exposed army from a secured position.[46] Henry II ordered the clearing of the woods on either side to widen the passage through the valley, and to lessen the exposure of his army.[46] The road his army traveled later became known as the Ffordd y Saeson, the English Road, and leads through heath and bog towards the Dee.[46] In a dry summer the moors may have been passable, but "on this occasion the skies put on their most wintry aspect; and the rain fell in torrents [...] flooding the mountain meadows" until the great Angevin encampment became a "morass," wrote Lloyd.[46] In the face of "hurricane" force wind and rain, diminishing provisions and an exposed supply line stretching through hostile country subject to enemy raids, and with a demoralized army, Henry II was forced into a complete retreat without even a semblance of a victory.[46]

In frustration, Henry II had twenty-two Welsh hostages mutilated; the sons of Owain' supporters and allies, including two of Owain's own sons.[46] In addition to his failed campaign in Wales, Henry's mercenary Norse navy, which he had hired to harass the Welsh coast, turned out to be too few for use, and were disbanded without engagement.[46]

Henry II's Welsh campaign was a complete failure, with the king abandoning all plans for the conquest of Wales, returning to his court in Anjou and not returning to England for another four years.[46] Lloyd wrote:

It is true that [Henry II] did not cross swords with [Owain I], but the elements had done their work for [the Welsh]; the stars in their courses had fought against the pride of England and humbled it to the very dust. To conquer a land which was defended, not merely by the arms of its valiant and audacious sons, but also by tangled woods and impassable bogs, by piercing winds and pitiless storms of rain, seemed a hopeless task, and Henry resolved to no longer attempt it.[46]

Owain expanded his international diplomatic offensive against Henry II by sending an embassy to Louis VII of France in 1168, led by Arthur of Bardsey, Bishop of Bangor (1166–1177), who was charged with negotiating a joint alliance against Henry II.[45] With Henry II distracted by his widening quarrel with Thomas Becket, Owain's army recovered Tegeingl for Gwynedd by 1169.[45]

Like his father before him, Owain I promoted stability in upper Gwynedd as no foreign army was able to campaign past the Conwy, marking nearly 70 years of peace in upper Gwynedd and on Anglesey.

In his later reign Owain I was the styled princeps Wallensium, Latin for the Prince of the Welsh, a title of substance given his leadership of the Welsh and victory against the English king, wrote historian Dr. John Davies.[47] Additionally, Owain commissioned the Life of Gruffudd ap Cynan, the biography of his father in which Owain firmly asserted his primacy over other Welsh rulers by "absolute right through descent" from Rhodri the Great, according to Davies.[20] Owain I was the eldest male descendant of Rhodri the Great through paternal descent.

The adoption of the title prince (Latin princeps, Welsh twysog), rather than king (Latin rex, Welsh brenin), did not mean a diminution in status, according to Davies.[47] The use of the title prince was a recognition of the ruler of Gwynedd in relation to the wider international feudal world.[47] The princes of Gwynedd exercised greater status and prestige then the earls, counts, and dukes of the Angevin empire, suggesting a similar status as that of the King of Scots, himself nominally a vassal of the King of England, argued Davies.[47] As Welsh society became further influenced by feudal Europe, the princes of Gwynedd would in turn use feudalism to strengthen their own authority over lesser Welsh lords, a "two-edged sword" for the King of England, wrote Davies.[47] Though Gwynedd's princes recognized the de jure suzerainty of the King of England, there remained well-established Welsh law separate from English law, and were independent de facto, wrote Davies.[48]

Civil war and usurpation 1170–1195

Throughout Owain's life it is clear he favoured his eldest sons, born of "Pyfog the Irishwoman". Annals state that these two sons, Rhun ab Owain Gwynedd and Hywel ab Owain Gwynedd, were illegitimate, but it is worth pausing to consider that history is often written by the victors. Owain and his father, Gruffudd ap Cynan, had both drawn considerable strength from family connections they had maintained across the Irish Sea in Dublin, and it was these connections which had restored Gruffudd on several occasions to his throne and had provided his father, Cynan, with a place of refuge during the usurpations of the 11th century. It is therefore possible that Owain hoped to maintain this Irish connection by ensuring the succession of one of his sons born of this Irish woman, Pyfog. Furthermore, it seems illogical – given the fact Owain was so set on their succession and the respect he no doubt commanded in Ireland – that the mother of Rhun and Hywel was a mere commoner and that both those children were born out of wedlock. What the annals record, however, is that in 1146 the eldest son and designated heir, Rhun – a man who was acclaimed as a great warrior and the "flower of Celtic chivalry", according to J.E. Lloyd,- "died" mysteriously, and that Hywel, his natural brother, was proclaimed the new edling, or heir.

Hywel ab Owain Gwynedd duly succeeded his father in 1170, but the realm was plunged immediately into a civil war that appears to have been a conflict between two rival factions: a pro-Irish 'legitimists' faction seeking to ensure the succession of Hywel and protect the legacy of Owain Gwynedd and his father, and a second distinctly anti-Irish coalition headed by Owain's widow, the Princess-Dowager Cristen who promoted her own son Dafydd ab Owain as Prince of Gwynedd ahead of Hywel and any other senior son of Owain Gwynedd. The Princess-Dowager and Dafydd made their move, and within a few months of his succession Hywel was overthrown and killed at the Battle of Pentraeth in 1171.

Although the exact division of the spoils is unclear, Maelgwn appears to have gained Anglesey whilst the sons of Cynan held the cantrefs of Meirionnydd, Eifionydd and Ardudwy between them. However Dafydd appears to have been recognised as pre-eminent amongst them and was regarded in some way as the overall leader. Naturally, once he'd enjoyed some of the benefits of power, Dafydd felt disinclined to share, as well as no doubt nervous that he might also soon share the fate of his predecessor Hywel; in 1173 he acted against his brother Maelgwn and drove him into exile in Ireland thereby gaining possession of all Anglesey for himself.

The following year he expelled all his remaining family rivals and made himself master of all Gwynedd and in 1175 "seized through treachery" his brother Rhodri and imprisoned him for good measure. Thus Dafydd re-united all Gwynedd under his one rule and in order to strengthen his position he sought an agreement with Henry II. Due to his problems with the Church and Normandy, Henry was anxious to secure peace and order in Wales. It was agreed that Dafydd would marry Emma of Anjou, who was Henry's illegitimate half sister, and receive the manor of Ellesmere as dowry, but unlike his southern counterpart, Rhys ap Gruffudd, he received no 'official' recognition of his position in the north.

All this was done, as the Brut y Tywysogion explained, "because [Dafydd] thought he could hold his territory in peace thereby", but it proved insufficient. Before the end of 1175 Rhodri had escaped from captivity and gathered sufficient support to drive Dafydd from Anglesey and across the River Conwy. Faced with this turn of events, Dafydd and Rhodri agreed to divide Gwynedd between them. Thereafter Dafydd's realm was restricted to Gwynedd Is Conwy--i.e., the Perfeddwlad, the land between the rivers Conwy and the Dee—whilst Rhodri retained Anglesey and Gwynedd Uwch Conwy. Secure in his now-truncated realm, Dafydd now appears to have pushed ambition to one side and resolved to enjoy the quiet life. There is no record of him engaging in any further strife for the twenty years or so after the settlement of 1175. Dafydd may not have inherited the leadership abilities of his father but he had sufficient diplomatic qualities remaining to ensure he could live at peace with his neighbours. This appears to be the one quality recognised by his contemporaries as he was described by Giraldus Cambrensis as a man who showed "good faith and credit by observing a strict neutrality between the Welsh and English".

His brother Rhodri had a more eventful time and fell out with the descendants of Cynan. They acted against Rhodri in 1190 and drove him out of Gwynedd altogether. Rhodri fled to the safety of the Isle of Man only to be briefly reinstated in 1193 with the assistance of the Ragnvald, King of the Isles, and then driven out once more at the beginning of 1194.

Dafydd's nemesis proved to be his nephew Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, born most likely in the year 1173 and therefore only a child when all these events played out. Llywelyn's father Iorwerth Drwyndwn had been involved in the early stages of the dynastic struggles and most likely died sometime around 1174. As the century drew to a close Llywelyn became a young man and decided to stake his claim to power in Gwynedd. He conspired with his cousins Gruffudd and Maredudd and his uncle Rhodri and in the year 1194 they all united against Dafydd, defeated him at the Battle of Aberconwy and "drove him to flight and took from him all his territory except three castles".

Llywelyn the Great

See also Llywelyn ap Iorwerth

Llywelyn, later known as Llywelyn the Great, was sole ruler of Gwynedd by 1200, and made a treaty with King John of England the same year. Llywelyn's relations with John remained good for the next ten years. He married John's illegitimate daughter Joan, also known as Joanna, in 1205, and when John arrested Gwenwynwyn ab Owain of Powys in 1208 Llywelyn took the opportunity to annex southern Powys. In 1210 relations deteriorated and John invaded Gwynedd in 1211. Llywelyn was forced to seek terms and to give up all his lands east of the River Conwy, but was able to recover these lands the following year in alliance with the other Welsh princes. He later allied himself with the barons who forced John to sign Magna Carta in 1215. By 1216 he was the dominant power in Wales, holding a council at Aberdyfi that year to apportion lands to the other princes.

Following King John's death, Llywelyn concluded the Treaty of Worcester with his successor Henry III in 1218. During the next fifteen years Llywelyn was frequently involved in fighting with Marcher lords and sometimes with the king, but also made alliances with several of the major powers in the Marches. The Peace of Middle in 1234 marked the end of Llywelyn's military career as the agreed truce of two years was extended year by year for the remainder of his reign.

Llywelyn the Great was determined to enforce the right of legitimate sons in Welsh succession law to bring Gwynedd in line with other Christian countries in Europe. However, by promoting his younger son Dafydd he encountered considerable support for his elder son Gruffudd from traditionalists in Gwynedd, as well as dealing with his acts of revolt. But if he held him prisoner, the support for Gruffudd could not be transformed into anything more dangerous. Although Dafydd lost one of his most important supporters when his mother died in 1237, he retained the support of Ednyfed Fychan, the Seneschal of Gwynedd and the wielder of great political influence. After Llywelyn suffered a paralytic stroke in 1237, Dafydd took an increasing role in government. Dafydd ruled Gwynedd following his father's death in 1240.

Dafydd ap Llywelyn

While King Henry III of England had accepted Dafydd's claim to Gwynedd, he was not disposed to allow him to retain his father's conquests outside it. In 1241 Henry invaded Gwynedd, and Dafydd was forced to submit in late August. Under the terms of the Treaty of Gwerneigron, Dafydd gave up all his lands outside Gwynedd, and released his captive half-brother Gruffudd to Henry. However, any potential value Henry might have realized from cultivating Gruffudd as a rival claimant to Gwynedd was frustrated when Gruffudd fell to his death in March 1244 while trying to escape from the Tower of London by climbing down a knotted sheet.

With his main rival dead Dafydd formed an alliance with other Welsh rulers and began a campaign against the English occupation of parts of Wales. After savage fighting the campaign was successful until Dafydd's sudden natural death brought it to a halt. He died without issue and so the succession passed to Gruffudd's adult sons, Owain Goch ap Gruffydd and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, who divided the realm between them.

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd was in Gwynedd at the time of his succession to the throne and had fought alongside his uncle Dafydd during the last campaign of his reign. This gave him an advantage over his elder brother Owain who had been imprisoned in England with his father since 1242. Owain returned to Gwynedd – he apparently "escaped" or was released immediately after the news of Dafydd's death reached England. Llywelyn and Owain were able to come to agreement and the reduced territory of Gwynedd was divided between them.

In 1255 their younger sibling Dafydd ap Gruffudd reached maturity and Henry III, sensing an opportunity to create mischief, demanded that he be allowed his division of Gwynedd also. Llywelyn rejected this on the grounds that this would further weaken the realm and play into England's hands. Dafydd formed an alliance with Owain and at the Battle of Bryn Derwin met Llywelyn in battle. Llywelyn was victorious; imprisoning Owain and confiscating his lands. He also imprisoned Dafydd for a short period before coming to terms with him. This behavior of Dafydd's would become a nearly continuous pattern, until the end of the brothers' lives.

Between 1255 and 1258 Llywelyn orchestrated a campaign against England across all of Wales gaining allies in Deheubarth and Powys. By 1258 he was acknowledged by almost all the native rulers as Prince of Wales. In 1263 his brother Dafydd defected to England for reasons which are unclear, although it has been speculated that the death of their mother played a role.

The following year, 1264, the Baron's Revolt in England had reached its climax at the Battle of Lewes. Llywelyn signed the Treaty of Woodstock with Simon de Montfort thus forming an alliance against Henry III. De Montfort was soon defeated and killed at the Battle of Evesham by Prince Edward, eldest son of the English king; yet the peace between England and Wales held, being formalised at the Treaty of Montgomery in 1267. The title "Prince of Wales" was recognised by the King of England. All the native Welsh princes were to be vassals of Llywelyn and it is from this point that the independent history of the kingdom of Gwynedd comes to an end.

The Principality of Wales was to be a short-lived creation. As is explained in greater detail elsewhere, the relationship between England and Wales broke down following the death of Henry III in 1272. By 1276 Llywelyn had been declared a rebel by the new King Edward I who was determined to be the master of the whole island of Great Britain. Diplomatic pressure followed up by an enormous invasion force broke the unity of Wales and allowed the English army to quickly occupy large areas, forcing Llywelyn back into his Gwynedd heartland. With the capture of Môn and the Perfeddwlad, LLywelyn sued for peace and was forced to sign the Treaty of Aberconwy reducing his realm to almost the same extent as at the beginning of his reign in 1247--viz., the lands above the Conwy. Edward granted Dafydd some lands in the Perfeddwlad, including the cantrefi of Rhôs and Rhufoniog.

A confined Llywelyn appears to have put all of his hopes into stabilising the succession through children sired by his new wife Eleanor de Montfort (the daughter of Simon de Montfort and his Countess, Nell de Montfort; also first cousin of Edward I). Tragedy struck when she died during childbirth in 1282, giving birth to a daughter, Gwenllian ferch Llywelyn. This seems to have driven Llywelyn into what some historians have speculated to be a nervous breakdown and incapacitated him.

Dafydd then joined Llywelyn in a rebellion over English rule. In November 1282 the Archbishop of Canterbury, John Peckham, came to North Wales to mediate the conflict. Llywelyn was offered a bribe: one thousand pounds a year and an estate in England, if he would surrender his territory (which then extended at least to Gwynedd and Deheubarth) to Edward. Llywelyn rejected the offer. The next month, on 11 December 1282, Llywelyn was killed at Cilmeri in an ambush. His leaderless forces were routed shortly afterwards and Edward moved to occupy Powys and eastern Gwynedd.

Dafydd ap Gruffudd

After these events Dafydd ap Gruffydd proclaimed himself Prince of Wales. Dafydd continued the fight and kept the support of Goronowy ap Heilin, the Lord of Rhôs, as well as Hywel ap Rhys Gryg and his brother Rhys Wyndod, disinherited princes of Deheubarth.[49]

However, as the English forces encircled Snowdonia and his people starved he was soon moving desperately from one fort to another as effective resistance was systematically crushed. Dolwyddelan, which was at risk of becoming encircled, was first abandoned on 18 January 1283. After this Dolbadarn Castle served as his base but by March this noble site in the heart of Snowdonia was also threatened forcing his departure. Finally, Dafydd moved his headquarters south to Castell y Bere near Llanfihangel-y-pennant. As the situation deteriorated it seems most likely that Dafydd and his family hoped to remain at Y Bere just long enough to avoid the worst of the Welsh winter before they were compelled to evacuate the site at the end of March in advance of the English forces who were manoeuvering to place it under siege. From this point forwards the prince, his family and the remains of his government were fugitives sleeping outdoors, forced to keep moving from place to place to avoid capture. Castell Y Bere's starving garrison would eventually surrender on 25 April. After the fall of Y Bere, Dafydd's movements are speculative but he is recorded in May 1283 leading raids from the mountains supported to the bitter end by Goronwy ap Heilin, Hywel ap Rhys and his brother Rhys Wyndod.[50]

The last months saw inward disintegration as well as submission to superior force. Nevertheless, Goronwy ap Heilin had committed himself to the struggle and died in rebellion, alongside the disinherited princes who stood with Dafydd ap Gruffudd in the last springtime of the principality of Wales, diehards who knew that theirs was not the heroism of a new beginning but the ultimate stand of the very last cohort clutching the figment of the political order that they had once been privileged to know.[49]

On 22 June 1283, Dafydd ap Gruffudd was captured in the uplands above Abergwyngregyn close to Bera Mawr in a secret hiding place recorded as "Nanhysglain". The site was no more than a hovel in a bog which may have been used previously by religious hermits. It is recorded that Dafydd, who had been betrayed, was "severely injured" during his capture. It is likely that his wife, daughters, niece and one of his sons were captured alongside him. His eldest son, Llywelyn ap Dafydd (aged about 15), was not there at the time because it is recorded that King Edward issued specific orders "ad querendum filium David primogenitum" to have him apprehended. Llywelyn ap Dafydd was detained later by "men of his own tongue" and taken into royal custody on 29 June. Following this any organised resistance ended until the uprising of Madog ap Llywelyn some eleven years later.

Dafydd was taken to Edward on the night of his capture, then moved under heavy guard by way of Chester to Shrewsbury where in October he was hanged, drawn and quartered. He holds the distinction of being the first person to be executed by the Crown for the crime of "treason."

End of independence

Following the death of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in 1282, and the execution of his brother Dafydd ap Gruffydd the following year, eight centuries of independent rule by the house of Gwynedd came to an end, and the kingdom, which had long been one of the final holdouts to total English domination of Wales, was annexed to England. The remaining important members of the ruling house were all arrested and imprisoned for the remainder of their lives (Dafydd's sons Llywelyn ap Dafydd and Owain ap Dafydd in Bristol Castle, his daughters and niece in convents). Under the terms of the Statute of Rhuddlan in 1284 the Kingdom of Gwynedd was broken up and re-organised into the English county model which created the counties of Anglesey, Carnarvonshire, Merionethshire, Denbighshire and Flintshire.

The Pura Walia (the new counties which had been Gwynedd plus Carmarthenshire and Cardiganshire) continued to be within a nominal Principality of Wales ruled by the Council of Wales at Ludlow as a part of the English crown. The title "Prince of Wales" was retained by the sovereign to be eventually awarded to his son, Prince Edward (later Edward II). The Welsh Marches would be merged with the principality in 1534 under the Council of Wales and the Marches until all separate governance for Wales as an administrative entity was abolished in 1689.

There were many Gwynedd-based rebellions after 1284 with varying degrees of success with most being led by peripheral members of the old royal house. In particular the rebellions of Prince Madoc in 1294 and of Owain Lawgoch (the great-nephew of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd) between 1372–1378 are most notable. Because of this the old royal house was purged and any surviving members went into hiding. A final rebellion in 1400 led by Owain Glyndŵr, a member of the rival royal house of Powys, also drew considerable support from within Gwynedd.

Military

According to Sir John Edward Lloyd, the challenges of campaigning in Wales were exposed during the 20-year Norman invasion.[23] If a defender could bar any road, control any river-crossing or mountain pass, and control the coastline around Wales, then the risks of extended campaigning in Wales were too great.[23]

The Welsh method of warfare during the reign of Henry II is described by Gerald of Wales in his work Descriptio Cambriae written c. 1190:

Their mode of fighting consists in chasing the enemy or in retreating. This light-armed people, relying more on their activity than on their strength, cannot struggle for the field of battle, enter into close engagement, or endure long and severe actions...though defeated and put to flight on one day, they are ready to resume the combat on the next, neither dejected by their loss, nor by their dishonour; and although, perhaps, they do not display great fortitude in open engagements and regular conflicts, yet they harass the enemy by ambuscades and nightly sallies. Hence, neither oppressed by hunger or cold, not fatigued by martial labours, nor despondent in adversity, but ready, after a defeat, to return immediately to action, and again endure the dangers of war.

--The Historical Works of Giraldus Cambrensis translated by Sir Richard Colt-Hoare (1894), p.511

The Welsh were revered for the skills of their bowmen. Additionally, the Welsh learned from their Norman rivals.[23] During the generations of warfare and close contact with the Normans, Gruffudd ap Cynan and other Welsh leaders learned the arts of knighthood and adapted them for Wales.[23] By Gruffudd's death in 1137 Gwynedd could field hundreds of heavy well-armed cavalry as well as their traditional bowmen and infantry.[23]

They make use of light arms, which do not impede their agility, small coats of mail, bundles of arrows, and long lances, helmets and shields, and more rarely greaves plated with iron. The higher class go to battle mounted on swift and generous steeds, which their country produces; but the greater part of the people fight on foot, on account of the marshy nature and unevenness of the soil. The horsemen, as their situation or occasion requires, willingly serve as infantry, in attacking or retreating; and they either walk bare-footed, or make use of high shoes, roughly constructed with untanned leather. In time of peace, the young men, by penetrating the deep recesses of the woods, and climbing the tops of mountains, learn by practice to endure fatigue through day and night.

--The Historical Works of Giraldus Cambrensis translated by Sir Richard Colt-Hoare (1894), p.491

In the end, Wales was defeated militarily by the improved ability of the English navy to blockade or seize areas essential for agricultural production such as Anglesey. With control of the Menai Strait, an invading army could regroup on Anglesey; without control of the Menai an army could be stranded there; and any occupying force on Anglesey could deny the vast harvest of the island to the Welsh.[24]

Lack of food would force the disbandment of any large Welsh force besieged within the mountains. Following the occupation Welsh soldiers were conscripted to serve in the English Army. During the revolt of Owain Glyndŵr the Welsh adapted the new skills they had learnt to guerrilla tactics and lightning raids. Owain Glyndŵr reputedly used the mountains with such advantage that many of the exasperated English soldiery suspected him of being a magician able to control the natural elements.

Administration

In early times Gwynedd (or Venedotia) may have been ruled from Chester. After the Battle of Chester in 613 when the city fell to the Anglo-Saxons the royal court moved west to the stronghold at Deganwy Castle near modern Conwy. This site was destroyed in 860 and afterwards Aberffraw on Anglesey became the principal power base, with exceptions such as Gruffydd ap Llywelyn's court at Rhuddlan. However, as the English fleet became more powerful and particularly after the Norman colonization of Ireland began it became indefensible and from about 1200 until 1283 the home and headquarters of the Princes was Abergwyngregyn or simply just "Aber" (its shortened form adopted by the Crown of England after the conquest). Joan, Lady of Wales, died there in 1237; Dafydd ap Llywelyn in 1246; Eleanor de Montfort, Lady of Wales, wife of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, Prince of Wales ("Tywysog Cymru" in modern Welsh), on 19 June 1282, giving birth to a daughter, Gwenllian. The royal home was occupied and expropriated by the English Crown in early 1283.

The traditional sphere of Aberffraw's influence in north Wales included Ynys Môn as their early seat of authority, and Gwynedd Uwch Conwy (Gwynedd above the Conwy, or upper Gwynedd), and the Perfeddwlad (the Middle Country) also known as Gwynedd Is Conwy (Gwynedd below the Conwy, or lower Gwynedd). Additional lands were acquired through vassalage or conquest, and by regaining lands lost to Marcher lords, particularly that of Ceredigion, Powys Fadog, and Powys Wenwynwyn. However these areas were always considered an addition to Gwynedd, never part of it.

The extent of the kingdom varied with the strength of the current ruler. Gwynedd was traditionally divided into "Gwynedd Uwch Conwy" and "Gwynedd Is Conwy" (with the River Conwy forming the dividing line between the two), which included Môn (Anglesey). The kingdom was administered under Welsh custom through thirteen Cantrefi each containing, in theory, one hundred settlements or Trefi. Most cantrefs were also divided into cymydau (English commotes).

Ynys Môn

| Commote | Modern local | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Aberffraw | Aberffraw | Historic seat of rulers of Gwynedd |

| Cemais | Cemaes | |

| Talebolyon | ||

| Llan-faes | Llan-maes | |

| Penrhos | Penrhos | |

| Rhosyr | Newborough, Niwbro | in 1294, refounded to house displaced villagers from Llanfaes |

Gwynedd Uwch Conwy

Gwynedd above the Conwy, or upper Gwynedd

Cantref Arllechwedd

| Commote | Modern local | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Arllechwedd Uchaf | Abergwyngregyn, Conwy County Borough | |

| Arllechwedd Isaf | Trefriw, Conwy County Borough |

| Commote | Modern local | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Arfon Uwch Gwyrfai | Gwynedd | Arfon above Gwyrfai |

| Arfon Is Gwyrfai | Gwynedd | Arfon beneath Gwyrfai |

| Commote | Modern local | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ardudwy | Meirionnydd area within Gwynedd | |

| Eifionydd | Dwyfor area within Gwynedd | Named after Eifion ap Dunod ap Cunedda |

| Commote | Modern local | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Dinllaen | Dwyfor council in Gwynedd county | |

| Cymydmaen | Dwyfor council in Gwynedd county | |

| Cafflogion |

| Commote | Modern local | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ystumaner | Merionethshire council in Gwynedd county | |

| Tal-y-bont |

Gwynedd Is Conwy

Also known as Perfeddwlad, or "the Middle Country" or Gwynedd Is Conwy (Gwynedd below the Conwy, or lower Gwynedd)

- Cantref Tegeingl:

- Cwnsyllt

- Prestatyn

- Rhuddlan

- Dyffryn Clwyd:

- Colion

- Llannerch

- Dogfeiling

- Rhufoniog

- Ceinmeirch

- Uwch Aled

- Is Aled

- Cantref Rhos

- Uwch Dulas

- Is Dulas

- Y Creuddyn

Legacy

Following Edward's conquest, the lands of Gwynedd proper were divided among the English counties of Anglesey, Caernarfonshire, Merionethshire, Denbighshire, and Flintshire. The Local Government Act 1972 reformed these, creating a new county (now called a "preserved county") of Gwynedd which comprised Anglesey and Llyn, Arfon, Dunoding, and Meirionydd on the mainland. The modern principal area of Gwynedd established by the Local Government (Wales) Act 1994 no longer includes Anglesey.

See also

Notes

- Old Welsh (until 12th century)

Middle Welsh (12th–14th century) - British Latin in use until 8th century. Medieval Latin used thereafter for legal and liturgical purposes.

References

Citations

- Wade-Evans, Arthur. Welsh Medieval Law. Oxford Univ., 1909. Accessed 1 Feb 2013.

- Bradley, A.G. Owen Glyndwr and the Last Struggle for Welsh Independence. G.P. Putnam's Sons (New York), 1901. Accessed 1 Feb 2013.

- Jenkins, John. Poetry of Wales. Houlston & Sons (London), 1873. Accessed 1 Feb 2013.

- Lewis, Timothy. A glossary of mediaeval Welsh law, based upon the Black book of Chirk. Univ. Press (Manchester), 1913.

- History of Gwynedd during the High Middle Ages#Aberdyfi.2C Worcester.2C and Strata Florida.3B 1216.E2.80.931240|Aberdyfi

- Davies, John. A History of Wales. Penguin (New York), 1994. ISBN 0-14-014581-8.

- Harleian MS 3859. Op. cit. Fitzpatrick-Matthews, K. "Harleian Genealogies". Accessed 29 Jan 2013.

- Hamp, Eric P., 'Goidil, Feni, Gwynedd', Proc. Harvard Celtic Colloquium 12 (1995) 43–50.

- Koch, John T., Celtic Culture, ABC-CLIO, 2006, p. 867.

- Koch, John T., The Gododdin of Aneirin, University of Wales, 1997, p. xcviii.

- Matasović, Ranko, Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic, 2009, p. 414; p. 418.

- Ptolemy, Geography 2.1

- Christopher A. Snyder (2003), The Britons, Blackwell Publishing

- Koch (2005), p. 738.

- Professor Bryan Ward-Perkins, “Why Did the Anglo-Saxons Not Become More British” Trinity College, Oxford, 2000

- "It took until 1282, when Edward I conquered Gwynedd, for the last part of Roman Britain to fall. Indeed a strong case can be made for Gwynedd as the very last part of the entire Roman Empire, east and west, to fall to the barbarians. (If we take into account of the temporary capture of Constantinople by ‘Franks’ in 1204, and of various Persian, Slav, Avar, and Seljuk invasions of Byzantine territory.)" Ward-Perkins was elaborating on an observation by J. Campbell, The Anglo-Saxons (Oxford, 1982), p19.

- Bertram Colgrave; R. A. B. Mynors, eds. (1969). "Bede's ecclesiastical history of the English people". Medieval Sourcebook: Bede (673735). Clarendon Press. volume: Book II. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- Lloyd (2004), p. 323.

- Chadwick, N. The Celts, Development of the Celtic Kingdoms (1971), p.86

- Davies (1994), Aberffraw primacy pg 116, patron of bards 117, Aberfraw relations with English crown pg 128, 135.

- Lloyd (2004), Aberffraw primacy pg 220

- Of the three surviving groups of manuscripts of the Cyfraith Hywel (all dating from the 12th century or later), one group recognizes Gwynedd exclusively, another Deheubarth exclusively, and the last both together. See: Wade-Evans, A.W. Welsh Medieval Law. "Introduction". Oxford Univ., 1909. Accessed 30 Jan 2013.

- Lloyd (2004), Recovers Gwynedd, Norman invasion, Battle of Anglesey Sound, pgs 21–22, 36, 39, 40, later years 76–77

- Davies (1994), Gruffydd ap Cynan; Battle of Mynydd Carn, Norman Invasion, pg 104–108, reconstructing Gwynedd pg 116,

- Warner (1997), Gruffydd's seizure pg 61, Escape from Chester, Kills Robert of Ruddlan, pg 63.

- Barlow (2000), p. 320-324.

- Bartlett (2000)

- Owen "Hervery (died 1131)" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online edition accessed March 6, 2008

- Wilcott, Darrell "The Ancestry of Edwin of Tegeingl"

- Davies (1994), Pura Wallia, Purae Wallie (the Welshries), Marchia Wallie pg 109, 127–130, 137, 141, 149, 166, 176.

- Lloyd (2004), Advances westard pp. 77–79.

- Lloyd (2004), Great Revolt, beginnings Gwenllian pg 80, taking Ceredigion, restores Welsh monks, Battle of Crug Mawr, 82–85.

- Warner (1997), Gwenllian pg 69, 79

- Lloyd (2004), Gruffydd's legacy pg 79, 80.

- Lloyd (2004), Gruffydd Gwynedd, Gruffydd Cyfeiliog, p. 93.

- Lloyd (2004), pp. 85, 93, 104.

- Lloyd (2004), pp. 94–95.

- Lloyd (2004), Cadwaladr's betrayal, p. 95.

- Warner (1997), Cadwaladr and Anarawd p. 80.

- Lloyd (2004), Rhun's death, p. 96.

- Lloyd (2004), Owain takes Iâl, Ruddlan, Tegeingl, pp. 96–98.

- Lloyd (2004), Owain and Henry II, pp. 99, 1070.

- Lloyd (2004), Owain 1160–1170, pp. 107–109.

- Davies (1994), Henry and Becket, Owain's leadership in 1166, Owain recaptures Tegeingl, pg125 Gwynedd's embassy to France pg 125,126

- Lloyd (2004), Henry's invasion plans pg 111, Welsh drawn together, pg 112, Angevin advance into Wales 112, 113, Henry II's campaign failure, pg 113, 114.

- Davies (1994), English King's suzerainty of Wales and Scotland, pg 103, Welsh princely titles pg128, 129

- Davies (1994), emerging defacto statehood pg 148

- Smith, p. 577.

- Smith, p. 576.

Sources

- BBC Wales/History, The emergence of the principality of Wales extracted 26 March 2008

- Barlow, Frank (2000). William Rufus. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08291-6.

- Bartlett, Robert (2000). England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings: 1075–1225. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-822741-8.

- Davies, John (2002). The Celts. New York: Cassell Illustrated. ISBN 1-84188-188-0.

- Evans, Gwynfor (2004). Cymru O Hud. Abergwyngregyn: Y Lolfa. ISBN 0-86243-545-5.

- Koch, John (2005). Celtic Culture: a historical encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

- Morris, John E. (1996). The Welsh Wars of Edward I. Conshohocken, PA.: Combined Books. ISBN 0-938289-67-5.

- Lloyd, J. E. (2004). A History of Wales; From the Norman Invasion to the Edwardian Conquest. New York: Barnes & Noble Publishing, Inc. ISBN 0-7607-5241-9.

- Smith, Beverley J. (2001). Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, Prince of Wales. University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-1474-6.

- Stephenson, David (1984). The governance of Gwynedd. University of Wales Press. ISBN 0-7083-0850-3.

- Warner, Philip (1997). Famous Welsh Battles. New York: Barnes & Noble Publishing, Inc. ISBN 0-7607-0466-X.