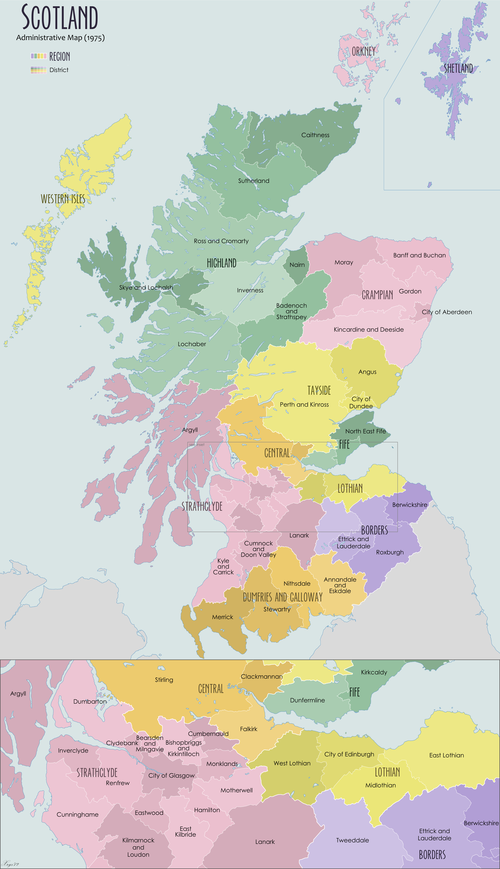

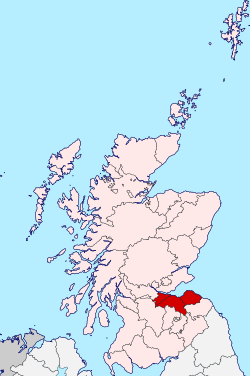

Lothian

Lothian (/ˈloʊðiən/; Scots: Lowden, Loudan, -en, -o(u)n;[2] Scottish Gaelic: Lodainn [ˈl̪ˠot̪aɲ]) is a region of the Scottish Lowlands, lying between the southern shore of the Firth of Forth and the Lammermuir Hills and the Moorfoot Hills. The principal settlement is the Scottish capital, Edinburgh, while other significant towns include Livingston, Linlithgow, Bathgate, Queensferry, Dalkeith, Bonnyrigg, Penicuik, Musselburgh, Prestonpans, North Berwick, Dunbar, and Haddington.

Lothian | |

|---|---|

| |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,720 km2 (666 sq mi) |

| Population (2014)[1] | |

| • Total | 858,090 |

| • Density | 497/km2 (1,288/sq mi) |

Historically, the term Lothian referred to a province encompassing most of what is now southeastern Scotland. In the 7th century it came under the control of the Anglian kingdom of Bernicia, the northern part of the later kingdom of Northumbria, but the Angles' grip on Lothian was quickly weakened following the Battle of Nechtansmere in which they were defeated by the Picts. Lothian was annexed to the Kingdom of Scotland around the 10th century.[3]

Subsequent Scottish history saw the region subdivided into three counties—Midlothian, East Lothian, and West Lothian—leading to the popular designation of "the Lothians".

Etymology

The origin of the name is debated. It perhaps comes from the British *Lugudūniānā (Lleuddiniawn in Modern Welsh spelling) meaning "country of the fort of Lugus", the latter being a Celtic god of commerce.[4] Alternatively it may take its name from a watercourse which flows through the region, now known as the Lothian Burn,[note 1] the name of which comes from either the British lutna meaning "dark or muddy stream",[note 2][5] *lǭd, with a meaning associated with flooding (c.f. Leeds),[6] or lǖch, meaning "bright, shining".[6]

A popular legend is that the name comes from King Lot, who is king of Lothian in the Arthurian legend. The usual Latin form of the name is Laudonia.[5]

Lothian under the control of the Angles

Lothian was settled by Angles at an early stage and formed part of the Kingdom of Bernicia, which extended south into present-day Northumberland. Many place names in the Lothians and Scottish Borders demonstrate that the English language became firmly established in the region from the sixth century onwards. In due course, Bernicia united with Deira to form the Kingdom of Northumbria. Important Anglo Saxon structural remains have been found in Aberlady along with various artefacts such as an early 9th century Anglo Saxon coin.[7]

Little is recorded of Lothian's history specifically at this time. After the Norse-speaking viking Great Army conquered southern Northumbria (including areas that would later become Yorkshire), northern Northumbria – centred on the former Anglian kingdom of Bernicia – was cut off from the other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. How much Norse influence spread north of the River Tees is uncertain. Bernicia continued as a distinct territory, sometimes described as having a king, at other times an ealdorman (earl). Bernicia became distinct from other English territories at this time due to its links with the other Christian kingdoms in what is present-day Scotland and seems to have little to do with the Norse-controlled areas to the south. Roger of Wendover wrote that Edgar, King of the English granted Laudian to Kenneth II, King of Scots in 973 on condition that he come to court whenever the English king or his successors wore his crown. It is widely accepted by medieval historians that this marks the point at which Lothian became part of Scotland. The River Tweed became the de facto Anglo-Scottish border following the Battle of Carham in 1018.

William the Conqueror invaded Lothian and crossed over the River Forth[8] but was not able to conquer it. At this time Lothian appears in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as Loðen or Loþen. As late as 1091, the Chronicle describes how the Scottish king, Malcolm Canmore, "went with his army out of Scotland into Lothian", and in the reign of King David, the people living in Lothian are described as "English" subjects of the king. However, this Anglo-Saxon Chronicle may not reflect Scottish thinking on the status of Lothian.

Language

In the post-Roman period, Lothian was dominated by British-speakers whose language is generally called Cumbric and was closely related to Welsh. In Welsh tradition Lothian is part of the "Old North" (Hen Ogledd). Reminders exist in British place-names like Tranent, Linlithgow and Penicuik.[9]

During the Anglo-Saxon period, the Northumbrian dialect of Old English came to be spoken in the region. Initially confined to Lothian and the Borders, the language would grow, change, and spread across the lowlands of Scotland, becoming the Scots language. The dialects of the modern Lothians are usually considered to be part of Central Scots. Place names in the Lothians of Anglian origin include Haddington, Ingliston, and Broxburn.

Although one of the few areas of mainland Scotland where the Gaelic language was never dominant, the presence of some Gaelic place-names,[9][10] e.g. Dalry, Currie, Balerno and Cockenzie, has been attributed to the "temporary occupation...[and] the presence of a landowning Gaelic-speaking aristocracy and their followers for something like 150–200 years."[11]

Local government

The Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973 abolished the county councils and burgh corporations, replacing them with regions and districts. Lothian Regional Council formally took over responsibility from the old county councils in May 1975. The Lothian region was split into four districts: East, Mid and West Lothian, and the City of Edinburgh. The former had more or less identical boundaries to the county council it replaced, but West and Mid Lothian had large amounts of land taken from them to form the City of Edinburgh district. The council was responsible for education, social work, water, sewerage, and transport (including local buses within Edinburgh).

The two-tier system was ended by the Local Government etc. (Scotland) Act 1994. Lothian Regional Council was replaced by four unitary councils based on the former districts.

Notes

- Also known as the Burdiehouse, Niddrie, or Brunstane Burn as it passes through those neighbourhoods.

- In contrast to the nearby Peffer Burn, the name of which comes from pefr, 'clear stream'.

References

- "Estimated population by sex, single year of age and administrative area, mid-2014" (PDF). National Records of Scotland. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- "Dictionary of the Scots Language :: SND :: Lowden prop. n". Dsl.ac.uk. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- "Ancient Lothian Timeline". Cyberscotia.net. Archived from the original on 2010-08-21. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- Koch, John, Celtic Culture, ABC-CLIO, 2006, p. 1191.

- Harris, Stuart (2002). The Place Names of Edinburgh: their Origins and History. London, England; Edinburgh, Scotland: Steve Savage Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-1904246060.

- James, Alan. "A Guide to the Place-Name Evidence" (PDF). SPNS - The Brittonic Language in the Old North. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-13. Retrieved 2018-11-25.

- "Important Anglo Saxon remains discovered in East Lothian". www.historyscotland.com. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

- "Ancient Lothian". Cyberscotia.net. Archived from the original on 2010-12-05. Retrieved 2007-02-22.

- Craig Cockburn (2005-11-02). "Gaelic roots need to be unearthed". BBC News.

- W. F. H. Nicolaisen (2001). Scottish Place Names. John Donald Publishers. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-85976-556-5.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Lothian. |