Battle of Lincoln (1141)

The Battle of Lincoln, or the First Battle of Lincoln, occurred on 2 February 1141 between King Stephen of England and forces loyal to Empress Matilda. Stephen was captured during the battle, imprisoned, and effectively deposed while Matilda ruled for a short time.[1][2]

Account

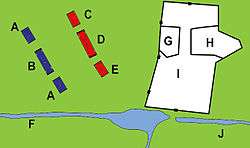

The forces of King Stephen of England had been besieging Lincoln Castle but were themselves attacked by a relief force loyal to Empress Matilda and commanded by Robert, 1st Earl of Gloucester, Matilda's half-brother. The Angevin army consisted of the divisions of Robert's men, those of Ranulf, Earl of Chester and those disinherited by Stephen, while on the flank was a mass of Welsh troops led by Madog ap Maredudd, Lord of Powys, and Cadwaladr ap Gruffydd. Cadwaladr was the brother of Owain, Prince of Gwynedd, but Owain did not support any side in the Anarchy. Stephen's force included William of Ypres; Simon of Senlis; Gilbert of Hertford; William of Aumale, Alan of Richmond and Hugh Bigod but was markedly short of cavalry.

As soon as the battle was joined, the majority of the leading magnates fled the king. Other important magnates captured with the king were Baldwin fitz Gilbert; Bernard de Balliol, Roger de Mowbray; Richard de Courcy; William Peverel of Nottingham; Gilbert de Gant; Ingelram de Say; Ilbert de Lacy and Richard fitzUrse, all men of respected baronial families; it had only been the Earls who had fled.

Even as the royal troops listened to the exhortations of Stephen's lieutenant, Baldwin fitz Gilbert, the advancing enemy was heard and soon the disinherited Angevin knights charged the cavalry of the five earls. On the left Earl William Aumale of York and William Ypres charged and smashed the poorly armed, 'but full of spirits', Welsh division but were themselves in turn routed 'in a moment' by the well-ordered military might of Earl Ranulf who stood out from the mass in 'his bright armour'. The earls, outnumbered and outfought, were soon put to flight and many of their men were killed and captured. King Stephen and his knights were rapidly surrounded by the Angevin force.

Then might you have seen a dreadful aspect of battle, on every quarter around the king's troop fire flashing from the meeting of swords and helmets – a dreadful crash, a terrific clamour – at which the hills re-echoed, the city walls resounded. With horses spurred on, they charged the king's troop, slew some, wounded others, and dragging some away, made them prisoners.

No rest, no breathing time was granted them, except in the quarter where stood that most valiant king, as the foe dreaded the incomparable force of his blows. The earl of Chester, on perceiving this, envying the king his glory, rushed upon him with all the weight of his armed men. Then was seen the might of the king, equal to a thunderbolt, slaying some with his immense battle-axe, and striking others down.

Then arose the shouts afresh, all rushing against him and him against all. At length through the number of the blows, the king's battle-axe was broken asunder. Instantly, with his right hand, drawing his sword, well worthy of a king, he marvellously waged the combat, until the sword as well was broken asunder.

On seeing this William Kahamnes [i.e. William de Keynes],[3] a most powerful knight, rushed upon the king, and seizing him by the helmet, cried with a loud voice, "Hither, all of you come hither! I have taken the king!"

— Roger de Hoveden, writing in the late 12th century[4]

The rest of his division fought on with no hope of escape until all were killed or had surrendered. Baldwin fitz Richard and Richard fitz Urse 'having received many wounds, and, by their determined resistance, having gained immortal honour' were taken prisoner.

After fierce fighting in the city's streets, Stephen's forces were defeated.[1] Stephen himself was captured and taken to Bristol, where he was imprisoned. He was subsequently exchanged for Robert of Gloucester, who was later captured in the Rout of Winchester the following September. This ended Matilda's brief ascendancy in the wars with Stephen.[2]

Incidental information

The Welsh contingent of the Angevin forces included Maredudd and Cadwgan,[5] two of the five sons of Madog ap Idnerth, who (when he lived) was the ruling prince of Fferllys.[5] Conversely, Stephen was aided by prominent Marcher Lords, like Hugh de Mortimer.[5] Following the Battle, his cause seeming lost, Hugh turned his attention to Fferllys, and invaded its northern parts the following year, killing Cadwgan (and Cadwgan's brother Hywel).[5] In 1146, he invaded the south of Fferllys, and killed Maredudd.[5] Matlida's son, Henry, forced Hugh to surrender his Welsh possessions;[6] Fferllys was divided between Madog's surviving sons, Cadwallon (who received Maelienydd) and Einion Clud (who received Elfael).[5]

In fiction

This battle is featured in the historical novel The Pillars of the Earth by Ken Follett, and is described almost as it happened, including the capture of King Stephen and his subsequent exchange.

Similarly, it is recounted in When Christ and His Saints Slept by Sharon Penman.

The battle of Lincoln is also an important plot element in Dead Man's Ransom, a novel in the Brother Cadfael series by Edith Pargeter (writing as Ellis Peters).

An older novel, The Villains of the Piece (aka Oath and the Sword), by Graham Shelby, also has a chapter in it describing First Lincoln.

See also

References

- Bradbury, Jim (1985). The medieval archer. Boydell & Brewer. p. 53. ISBN 0-85115-194-9.

- Sewell, Richard Clarke (1846). Gesta Stephani. London: Sumptibus Societatis. pp. 70, 71.

- William de Keynes family tree Archived 2014-07-14 at the Wayback Machine, see also Keynes family

- Roger de Hoveden, Translated Henry T. Riley (1853). The Annals of Roger de Hoveden: Comprising The History of England and of Other Countries of Europe from A.D. 732 to A.D. 1201, Vol 1. H. G. Bohn. pp. 243, 244.

- Wales: A Historical Companion, Terry Breverton, entry for Lincoln, Battle of, 1141

- Henry II, W. L. Warren, 1973, London, p. 60

Further reading

- Ward, Jennifer C. (1989). "Royal Service and Reward: the Clare Family and the Crown, 1066-1154". Anglo~Norman Studies. 11: 261–278 (276). Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- Matthew, Donald (2002). King Stephen. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 102. ISBN 1-85285-272-0.