Anglesey

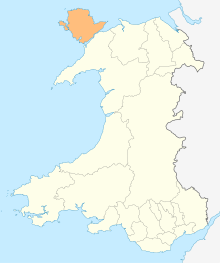

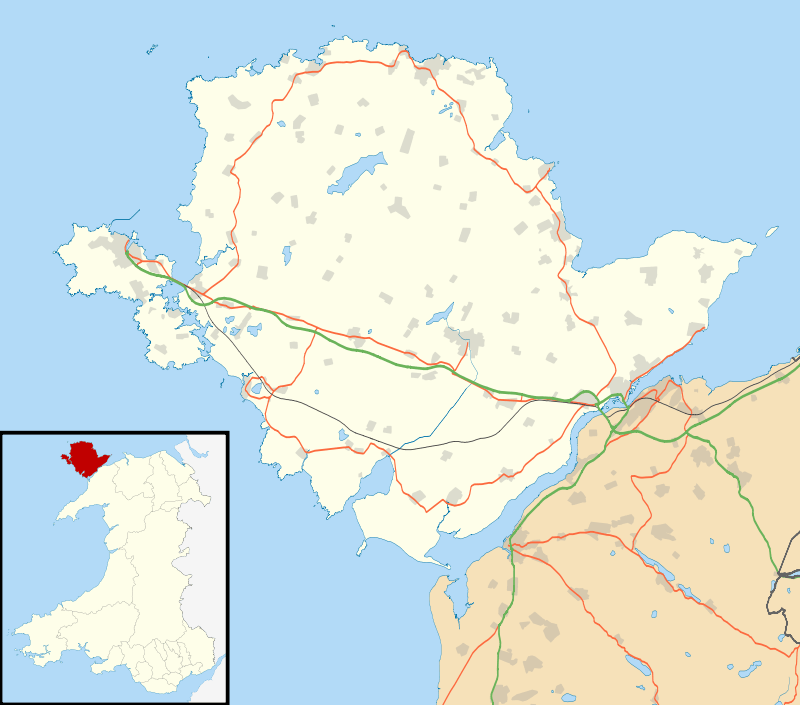

Anglesey (/ˈæŋɡəlsiː/; Welsh: Ynys Môn [ˈənɨs ˈmoːn]) is an island off the north-west coast of Wales. It forms the principal area (as Isle of Anglesey) and historic county of that name, which includes Holy Island to the west and some islets and skerries.[1] Anglesey island, at 260 square miles (673 km2), is by far the largest island in Wales, the seventh largest in the British Isles, largest in the Irish Sea and second most populous after the Isle of Man. The local government area of Isle of Anglesey County Council measures 276 square miles (715 km2),[2] with a 2011 census population of 69,751,[3] of whom 13,659 live on Holy Island. The Menai Strait between Anglesey and mainland Wales is spanned by the Menai Suspension Bridge, designed by Thomas Telford in 1826, and the Britannia Bridge, built in 1850 and replaced in 1980. The largest town is Holyhead, whose port handles over 2 million passengers a year to and from Ireland.[4] The next largest is Llangefni, seat of the county council. From 1974 to 1996 Anglesey was run as part of Gwynedd.[5] Most Anglesey inhabitants are Welsh speakers.[6] The name Ynys Môn is used for the UK Parliament and Senedd (Welsh Parliament) constituencies. The island is part of the LL postcode area (LL58–LL78).

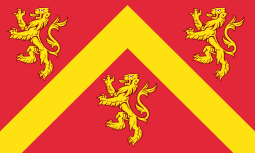

Isle of Anglesey Ynys Môn | |

|---|---|

Island | |

.jpg) View from the Anglesey Coastal Path | |

| |

| Sovereign State | United Kingdom |

| Constituent Country | Wales |

| County Council | Isle of Anglesey |

| Preserved County | Gwynedd |

| Admin HQ | Llangefni |

| Largest town | Holyhead |

| Government | |

| • Type |  Isle of Anglesey County Council |

| • Control | Commissioners |

| • Member of Parliament | |

| • Member of Senedd |

|

| • MEPs | Wales |

| Area | |

| • Total | 276 sq mi (714 km2) |

| Area rank | Ranked 9th |

| Population (2017) | |

| • Total | 69,961 |

| • Rank | Ranked 20th |

| • Density | 250/sq mi (98/km2) |

| • Density rank | Ranked 17th |

| • Ethnicity | 98.1% White |

| Welsh language | |

| • Rank | Ranked 2nd |

| • Any skills | 70.4% |

| Geocode | 00NA (ONS) W06000001 (GSS) |

| ISO 3166 code | GB-AGY |

| Website | www |

Name

The name of the island may be derived from the Old Norse; either Ǫngullsey "Hook Island"[7] or Ǫnglisey "Ǫngli's Island".[7][8] No record of such an Ǫngli survives,[9] but the placename was used by Viking raiders as early as the 10th century and was later adopted by the Normans during their invasions of Gwynedd.[10] The traditional folk etymology reading the name as the "Island of the Angles (English)"[11][12] may account for its Norman use but has no merit,[8] but the Angles' name itself is probably a cognate reference to the shape of the Angeln peninsula. All of them ultimately derive from the proposed Proto-Indo-European root *ank- ("to flex, bend, angle").[13] Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries and into the 20th, it was usually spelt Anglesea in documents.[11]

Ynys Môn, the island's Welsh name, was first recorded as Latin Mona by various Roman sources.[14][15][16] It was likewise known to the Saxons as Monez.[17] The Brittonic original was in the past taken to have meant "Island of the Cow".[11][18] This view is untenable according to modern scientific philology, and the etymology remains a mystery.

Poetic names for Anglesey include the Old Welsh Ynys Dywyll (Shady or Dark Isle) for its former groves and Ynys y Cedairn (Isle of the Brave) for its royal courts;[12] Gerald of Wales' Môn Mam Cymru ("Môn, Mother of Wales") for its productivity;[12] and Y fêl Ynys (Honey Isle).

History

There are numerous megalithic monuments and menhirs on Anglesey, testifying to the presence of humans in prehistory. Plas Newydd is near one of 28 cromlechs that remain on uplands overlooking the sea. The Welsh Triads claim that Anglesey was once part of the mainland.[11]

Historically, Anglesey has long been associated with the druids. In AD 60 the Roman general Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, determined to break the power of the druids, attacked the island using his amphibious Batavian contingent as a surprise vanguard assault[19] and then destroying the shrine and the nemeta (sacred groves). News of Boudica's revolt reached him just after his victory, causing him to withdraw his army before consolidating his conquest. The island was finally brought into the Roman Empire by Gnaeus Julius Agricola, the Roman governor of Britain, in AD 78. During the Roman occupation, the area was notable for the mining of copper. The foundations of Caer Gybi, a fort in Holyhead, are Roman, and the present road from Holyhead to Llanfairpwllgwyngyll was originally a Roman road.[20] The island was grouped by Ptolemy with Ireland ("Hibernia") rather than with Britain ("Albion").[21]

British Iron Age and Roman sites have been excavated and coins and ornaments discovered, especially by the 19th-century antiquarian William Owen Stanley.[22] After the Roman departure from Britain in the early 5th century, pirates from Ireland colonised Anglesey and the nearby Llŷn Peninsula. In response to this, Cunedda ap Edern, a Gododdin warlord from Scotland, came to the area and began to drive the Irish out. This was continued by his son Einion Yrth ap Cunedda and grandson Cadwallon Lawhir ap Einion; the last Irish invaders were finally defeated in battle in 470. As an island, Anglesey was in a good defensive position, and so Aberffraw became the site of the court, or Llys, of the Kingdom of Gwynedd. Apart from a devastating Danish raid in 853 it remained the capital until the 13th century, when improvements to the English navy made the location indefensible. Anglesey was also briefly the most southerly possession of the Norwegian Empire.

After the Irish, the island was invaded by Vikings — some of these raids were noted in famous sagas (see Menai Strait History) — and by Saxons, and Normans, before falling to Edward I of England in the 13th century.

Anglesey (together with Holy Island) is one of the 13 historic counties of Wales. In medieval times, before the conquest of Wales in 1283, Môn often had periods of temporary independence, as it was frequently bequeathed to the heirs of kings as a sub-kingdom of Gwynedd. The last times this occurred were a few years after 1171, following the death of Owain Gwynedd, when the island was inherited by Rhodri ab Owain Gwynedd, and between 1246 and c. 1255, when it was granted to Owain Goch as his share of the kingdom. After the conquest of Wales by Edward I, Anglesey was created a county under the terms of the Statute of Rhuddlan of 1284. Prior to this it had been divided into the cantrefi of Aberffraw, Rhosyr and Cemaes.

20th century

During the First World War, the Presbyterian minister and celebrity preacher John Williams toured the island as part of an effort to recruit young men to volunteer for a just war.[23] German POWs were kept on the island.[23]

By the end of the war, some 1,000 of the island's men had died while on active service.[23]

In 1936 the NSPCC opened its first branch on Anglesey.[24]

During the Second World War, Anglesey received Italian POWs.[23] The island was designated a reception zone, and was home to evacuee children from Liverpool and Manchester.[23] The island's location made it an ideal place to monitor German U-Boats operating in the Irish Sea. Around half a dozen airships operated out of Mona airfield to monitor submarine activity.[23]

In 1974, Anglesey became a district of the new large county of Gwynedd. The Local Government (Wales) Act 1994 abolished the 1974 county and the five districts on 1 April 1996. Anglesey became a separate unitary authority. In 2011, the Welsh Government appointed a panel of commissioners to administer the council, thus the elected members were not in control. The commissioners remained in control until an election was held in May 2013, restoring an elected Council. Before the period of direct administration, there had been a majority of independent councillors. Though members did not generally divide along party lines, these were organised into five non-partisan groups on the council, containing a mix of party and independent candidates. The position remains substantially unchanged since the election, although the Labour Party has formed a governing coalition with the independents.

The principal offices of the Isle of Anglesey County Council are in Llangefni, the county town.[25]

Geography

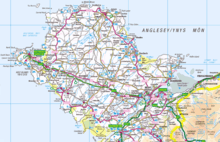

Anglesey is a relatively low-lying island, with low hills spaced evenly over the north of the island. The highest six are Holyhead Mountain, 220 metres (720 ft); Mynydd Bodafon, 178 metres (584 ft); Mynydd Llaneilian, 177 metres (581 ft); Mynydd y Garn, 170 metres (560 ft); Bwrdd Arthur, 164 metres (538 ft); and Mynydd Llwydiarth, 158 metres (518 ft). To the south and south-east, the island is separated from the Welsh mainland by the Menai Strait, which at its narrowest point is about 250 metres (270 yd) wide. In all other directions the island is surrounded by the Irish Sea. At 714 km2, it is the 51st largest island in Europe, (although technically Madeira is part of Africa), and just five square kilometres smaller than Singapore.

There are several small towns scattered around the island, making it quite evenly populated. The largest are Holyhead, Llangefni, Benllech, Menai Bridge, and Amlwch. Beaumaris (Welsh: Biwmares), in the east of the island, features Beaumaris Castle, built by Edward I as part of his Bastide Town campaign in North Wales. Beaumaris is a yachting centre, with many boats moored in the bay or off Gallows Point. The village of Newborough (Welsh: Niwbwrch), in the south, created when the townsfolk of Llanfaes were relocated to make way for the building of Beaumaris Castle, includes the site of Llys Rhosyr, another of the courts of the medieval Welsh princes, which features one of the oldest courtrooms in the United Kingdom. Llangefni is located in the centre and is the island's administrative centre. The town of Menai Bridge (Welsh: Porthaethwy, in the south-east) expanded when the first bridge to the mainland was being built, to accommodate workers and construction. Until then, Porthaethwy had been one of the principal ferry crossing points from the mainland. A short distance from this town lies Bryn Celli Ddu, a Stone Age burial mound.

Nearby is the village with the longest name in Europe, Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch, and Plas Newydd, ancestral home of the Marquesses of Anglesey. The town of Amlwch is situated in the northeast of the island and was once largely industrialised, having grown during the 18th century by supporting an important copper-mining industry at Parys Mountain.

.jpg)

Other villages and settlements include Cemaes, Pentraeth, Gaerwen, Dwyran, Bodedern, Malltraeth and Rhosneigr. The Anglesey Sea Zoo is a local tourist attraction, providing a descriptive look at local marine wildlife from common lobsters to congers. All the fish and crustaceans on display are caught around the island and placed in reconstructions of their natural habitat. The zoo also breeds lobsters commercially for food, and oysters, for pearls, both from local stocks. Sea salt (Halen Môn, evaporated from the local sea water), now produced in a modern facility nearby, was formerly produced at the Sea Zoo site.

There are a few natural lakes, mostly in the west, such as Llyn Llywenan, the largest on the island, Llyn Coron, and Cors Cerrig y Daran, but rivers are few and small. There are two large water supply reservoirs operated by Welsh Water. These are Llyn Alaw to the north of the island and Llyn Cefni in the centre of the island, which is fed by the headwaters of the Afon Cefni.

The climate is humid (though much less so than neighbouring mountainous Gwynedd) and generally equable, being influenced by the Gulf Stream. The land is of variable quality and it was probably much more fertile in the past. Anglesey is the home of the northernmost olive grove in Europe and presumably in the world.[26]

Coastal path

The rural coastline has been designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. It has many sandy beaches, notably along its east coast between the towns of Beaumaris and Amlwch and the west coast from Ynys Llanddwyn through Rhosneigr to the bays around Carmel Head. The north coast has dramatic cliffs with small bays[27] The Anglesey Coastal Path circumscribes the island. It is 124 miles (200 km) long and passes by/through 20 towns/villages. The official starting point is St Cybi's Church, Holyhead.[28]

Economy

Tourism is now the major economic activity on the island. Agriculture provides the secondary source of income for the economy, with local dairies being some of the most productive in the region.

Major industry is restricted to Holyhead (Caergybi), which until 30 September 2009 supported an aluminium smelter, and the Amlwch area, once a copper mining town. Nearby is the site of the former Wylfa Nuclear Power Station and a former bromine extraction plant. With construction starting in 1963, the two Wylfa reactors began producing electricity in 1971. One reactor was decommissioned in 2012 and the other in 2015. Plans were developed for a replacement reactor, planned by Horizon, a subsidiary of Hitachi, to start production in the 2020s.[29] The replacement has been enthusiastically endorsed by Anglesey Council and Welsh Assembly members, but protesters have raised doubts about the economic and safety claims made for the plant,[30] and in January 2019 Hitachi announced it was putting development work on hold, which meant the plant's future was put in serious doubt.[31]

Anglesey also has three wind farms on land,[32] and more than twenty offshore wind turbines near the north coast. There are plans for the world's first Tidal Flow turbines, near The Skerries, off the north coast,[33] and for a major biomass plant on Holy Island (Ynys Gybi). Developing such low-carbon energy assets to their full potential forms part of the Anglesey Energy Island project.[34]

When the aluminium smelter closed in September 2009, it reduced its workforce from 450 to 80; this has been a major blow to the island's economy, especially to Holyhead. The Royal Air Force station RAF Valley (Y Fali) is home to the RAF Fast Jet Training School and 22 Sqn Search and Rescue Helicopters, both units providing employment to about 500 civilians. RAF Valley is now the 22 Sqn Search and Rescue headquarters.

There is a wide range of smaller industries, mostly in industrial and business parks, especially at Llangefni and Gaerwen. These include an abattoir, fine chemical manufacturing, and factories for timber production, aluminium smelting, fish farming and food processing. The island is on one of the main road routes from Britain to Ireland, via ferries from Holyhead, off the west of Anglesey on Holy Island, serving Dún Laoghaire and Dublin Port.

Ecology and conservation

Much of Anglesey is used for relatively intensive cattle and sheep farming. However, there are several important wetland sites that have protected status. In addition, the several lakes all have significant ecological interest, including their support for a wide range of aquatic and semi-aquatic bird species. In the west, the Malltraeth Marshes are believed to support an occasional visiting bittern, and the nearby estuary of the Afon Cefni supports a bird population made internationally famous by the paintings of Charles Tunnicliffe, who lived for many years and died at Malltraeth on the Cefni estuary. The RAF airstrip at Mona is a nesting site for skylarks. The sheer cliff faces at South Stack near Holyhead provide nesting sites for huge numbers of auks, including puffins, razorbills and guillemots, together with choughs and peregrine falcons. Anglesey is home to several species of tern, including the roseate tern. Three sites on Anglesey are important for breeding terns – see Anglesey tern colonies.

There are marked occurrences of the Juncus subnodulosus–Cirsium palustre fen-meadow plant association, a habitat marked by certain hydrophilic grasses, sedges and forbs.[35]

Anglesey supports two of the UK's few remaining colonies of red squirrels, at Pentraeth and Newborough.[36]

Almost the entire coastline of Anglesey is designated as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) to protect the aesthetic appeal and variety of the island's coastal landscape and habitats from inappropriate development. The coastal zone of Anglesey was designated as an AONB in 1966 and confirmed as such in 1967.

The AONB is predominantly a coastal designation, covering most of Anglesey's 125 miles (201 km) coastline but also encompasses Holyhead Mountain and Mynydd Bodafon. Substantial areas of other land protected by the AONB form the backdrop to the coast. The AONB is about 221 km2 (85 sq mi) and it is the largest AONB in Wales, covering one third of the island.

A number of the habitats in Anglesey gain still greater protection through both UK and European designations of their nature conservation value. These include:

- 6 candidate Special Areas of Conservation (cSACs)

- 4 Special Protection Areas (SPAs)

- 1 National Nature Reserve

- 26 Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI)

- 52 Scheduled Ancient Monuments (SAMs)

These habitats support a variety of wildlife, such as harbour porpoises and marsh fritillary.

The AONB also takes in three sections of open, undeveloped coastline designated as Heritage Coast. These non-statutory designations complement the AONB and cover about 31 miles (50 km) of the coastline. The sections of Heritage Coast are:

- North Anglesey 28.6 km (17.8 mi)

- Holyhead Mountain 12.9 km (8.0 mi)

- Aberffraw Bay 7.7 km (4.8 mi)

Popular recreations include sailing, angling, cycling, walking, wind surfing and jet skiing. They place pressures and demands on the AONB, while contributing to the local economy.[37]

Abandoned nuclear plan

On 17 January 2019, Hitachi-Horizon Nuclear Power announced it was abandoning plans to build a nuclear plant on the Wylfa Newydd site in Anglesey. There had been concern that the start of the project might involve too much public expenditure, but Hitachi-Horizon say the decision to scrap has cost the company over £2 billion.[38][39][40][41]

Culture

Anglesey hosted the National Eisteddfod in 1957, 1983, 1999, and 2017.

It is also a member of the International Island Games Association. Anglesey's biggest successes were at the 1997 Island Games held in Jersey, (11th in the medals table, with two gold, three silver and nine bronze medals) and the 2005 Island Games in the Shetland Islands, (again 11th, with 4 gold, 2 silver and 2 bronze).

The annual Anglesey Show is held on the second Tuesday and Wednesday of August. Farmers from around the country compete in livestock rearing contests, including sheep and cattle.

Anglesey has featured in the Channel 4 archaeological television programme Time Team (series 14). The episode was transmitted on 4 February 2007.

The island hosts Gottwood, an electronic music and arts festival held each summer at the Carreglwyd estate. The Druidic college at Anglesey is referred to in the metal band Eluveitie's song "Inis Mona", an incorrect spelling of Ynys Môn.

Capital Cymru, a commercial contemporary hit radio station, also covers Gwynedd. Môn FM, a volunteer community radio station, broadcasts from the county town, Llangefni.

In 2018, the BBC began a three-part series entitled Anglesey: Island Lives, detailing the lives of several residents of the island. In the first episode, Kris Hughes, a noted companion of the Druid community and the Anglesey Druid Order, was followed as the order marked the Summer Solstice.[42]

Welsh language

Anglesey is a stronghold of the Welsh language and according to the 2011 census it was the local authority with the second highest proportion of Welsh speakers. The earlier percentages of Welsh speakers are these:

- 1901: 91%[43]

- 1911: 89%[43]

- 1921: 88%

- 1931: 87%

- 1951: 80%[44]

- 1961: 75%

- 1971: 66%

- 1981: 61%

- 1991: 62%

- 2001: 60%

- 2011: 57%

Today, Welsh is less widely used on the island, but remains the dominant language in certain areas, particularly in the centre, including the town of Llangefni, and some areas of the south coast. The island's five secondary schools vary widely in the percentage of their pupils who come from predominantly Welsh-speaking homes, as do the percentages who can speak Welsh:

- Ysgol David Hughes (in Menai Bridge): 33% come from Welsh-speaking homes; 90% "can speak Welsh."[45]

- Ysgol Gyfun Llangefni (in Llangefni): 68% of pupils speak Welsh as their first language; 87% of pupils take their exams through the medium of Welsh.

- Ysgol Syr Thomas Jones (in Amlwch): 34% of pupils come from Welsh-speaking homes; 82% sit the Welsh First Language General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE).

- Ysgol Uwchradd Bodedern (in Bodedern): 67% of pupils come from Welsh-speaking homes; "a majority" speak Welsh fluently.[46]

- Ysgol Uwchradd Caergybi (in Holyhead): 14% of pupils speak Welsh at home; 11% are taught the "Welsh First Language" curriculum.

Geology

The geology of Anglesey is notably complex and frequently targeted for geology field trips by schools and colleges. Younger strata in Anglesey rest upon a foundation of very old Precambrian rocks that appear at the surface in four areas:

- a western region including Holyhead and Llanfaethlu[11]

- a central area about Aberffraw and Trefdraeth[11]

- an eastern region which includes Newborough,[11] Gaerwen and Pentraeth

- a coastal region at Glyn Garth between Menai Bridge and Beaumaris[11]

These Precambrian rocks are schists and phyllites, often contorted and disturbed. The general line of strike of the formations in the island is from north-east to south-west.[11]} A belt of granitic rocks lies immediately north-west of the central Precambrian mass, reaching from Llanfaelog near the coast to the vicinity of Llanerchymedd. Between this granite and the Precambrian of Holyhead is a narrow tract of Ordovician slates and grits with Llandovery beds in places; this tract spreads out in the north of the island between Dulas Bay and Carmel Point. A small patch of Ordovician strata lies on the northern side of Beaumaris. In parts, these Ordovician rocks are much folded, crushed and metamorphosed, and they are associated with schists and altered volcanic rocks which are probably Precambrian. Between the eastern and central Precambrian masses Carboniferous rocks are found. The Carboniferous Limestone occupies a broad area south of Lligwy Bay and Pentraeth, and sends a narrow spur in a south-westerly direction by Llangefni to Malltraeth Sands. The limestone is underlain on the north-west by a red basement conglomerate and yellow sandstone (sometimes considered to be of Old Red Sandstone age). Limestone occurs again on the north coast around Llanfihangel and Llangoed; and in the south-west round Llanidan near the Menai Strait. Puffin Island is made of carboniferous limestone. Malltraeth marsh is occupied by Coal Measures, and a small patch of the same formation appears near Tal-y-foel Ferry on the Menai Strait. A patch of rhyolitic/felsitic rocks form Parys Mountain, where copper and iron ochre have been worked. Serpentine (Mona Marble) is found near Llanfair-yn-Neubwll and upon the opposite shore in Holyhead.[11]

Under the name GeoMôn, in recognition of its extraordinary geological heritage, the island gained membership of the European Geoparks Network in spring 2009.[47] and the Global Geoparks Network in September 2010.

Landmarks

- Anglesey Motor Racing Circuit

- Anglesey Sea Zoo near Dwyran

- Bays and beaches – Benllech, Cemlyn, Red Wharf, and Rhosneigr

- Beaumaris Castle and Gaol

- Cribinau – tidal island with 13th-century church

- Elin's Tower (Twr Elin) – RSPB reserve and the lighthouse at South Stack (Ynys Lawd) near Holyhead

- King Arthur's seat – near Beaumaris

- Llanfairpwllgwyngyll, one of the longest place names in the world

- Malltraeth – centre for bird life and home of wildlife artist Charles Tunnicliffe

- Moelfre – fishing village

- Parys Mountain – copper mine dating to the early Bronze Age

- Penmon – priory and dovecote

- Skerries Lighthouse – at the end of a low piece of submerged land, north-east of Holyhead

- Stone Science Museum – privately run fossil museum near Pentraeth[48]

- Swtan longhouse and museum – owned by the National Trust and managed by the local community

- Working windmill – Llanddeusant

- Ynys Llanddwyn (Llanddwyn Island) – tidal island

- St Cybi's Church Historic church in Holyhead

Notable people

Born in Anglesey

- Tony Adams – actor

- Stu Allan – radio and club DJ

- John C. Clarke – politician

- Grace Coddington – creative director for US Vogue, born 1941

- Charles Allen Duval – artist and writer (Beaumaris, 1810)

- Dawn French – actress, writer, comedian (Holyhead, 1957)

- Huw Garmon – actor (Anglesey, 1966)

- Hugh Griffith – Oscar-winning actor (Marianglas, 1912)

- Meinir Gwilym – singer and songwriter (Llangristiolus, 1983)

- Owain Gwynedd – prince (Anglesey, c. 1100)

- Hywel Gwynfryn – radio and TV personality (Llangefni, 1942)

- Aled Jones – singer and television presenter (Llandegfan, 1970)

- John Jones – amateur astronomer (Bryngwyn Bach, Dwyran 1818 – Bangor 1898); a.k.a. Ioan Bryngwyn Bach and Y Seryddwr

- William Jones – mathematician (Llanfihangel Tre'r Beirdd, 1675)

- Julian Lewis Jones portrays Karl Morris on the Sky 1 comedy Stella.

- John Morris-Jones – grammarian and poet (Llandrygarn, 1864)

- Edward Owen – 18th-century artist, notable for letters documenting life in London's art scene

- Goronwy Owen – poet (Llanfair Mathafarn Eithaf, 1723)

- Osian Roberts – association football player and manager (Bodffordd)

- Tecwyn Roberts - NASA aerospace engineer and Director of Networks at Goddard Space Flight Center (Llanddaniel Fab, 1925)

- Hugh Owen Thomas – pioneering orthopaedic surgeon (1833)

- Sefnyn – medieval court poet

- Owen Tudor – grandfather of Henry Tudor, married the widow of Henry V, which gave the Tudor dynasty a claim on the English throne.

- Kyffin Williams RA – landscape painter (Anglesey, 1918–2006)

- Andy Whitfield – actor (Amlwch, 1971–2011)

- Gareth Williams, employee of Britain's GCHQ signals intelligence agency

Lived in Anglesey

- Rachel Davies (Rahel o Fôn) – preacher

- Henry Austin Dobson – poet and essayist (Plymouth, Devon 1840)

- Taron Egerton – actor and star of Rocketman (moved to Wales aged 12)

- Gareth Glyn – composer and broadcaster (since 1978)

- Wayne Hennessey – footballer, currently goalkeeper with Crystal Palace and Wales (Bangor, 1987)

- Ian "Lemmy" Kilmister – heavy metal bass player and singer, front man of Motörhead (Stoke-on-Trent, 1945)

- Glenys Kinnock – politician (Holyhead, 1950s)

- The Marquesses of Anglesey – noble family from Plas Newydd, Llanfairpwll

- Matthew Maynard – cricketer (Oldham, Lancashire 1966)

- George North – Wales rugby union international (born King's Lynn, 1992; family moved to Anglesey in his early childhood)

- Gruff Rhys – Musician best known for being the leadman of Super Furry Animals grew up in Rachub, near Bethesda (Haverfordwest, 18 July 1970)

- Iain Duncan Smith, leader of the Conservative Party 2001–2003, attended HMS Conway School Ship Plas Newydd, Llanfairpwll, 1968–1972.

- Charles Tunnicliffe – wildlife artist (Langley, Macclesfield, 1901)

- Naomi Watts – Oscar -nominated actress (born Kent, 1968)

- Rex Whistler – artist (born Eltham, Kent 1905)

- Maurice Wilks – father of the Land Rover, which was test driven on Newborough and Llanddona beach

- Prince William, Duke of Cambridge – grandson of Queen Elizabeth II, and his wife Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge (2010–13)

- Clive Woodward – rugby union player and England / British Lions coach, attended HMS Conway School Ship Plas Newydd, Llanfairpwll, 1969–1974.

Schools

Secondary schools:

- Ysgol David Hughes, Menai Bridge

- Ysgol Gyfun Llangefni, Llangefni

- Ysgol Syr Thomas Jones, Amlwch

- Ysgol Uwchradd Bodedern, Bodedern

- Ysgol Uwchradd Caergybi, Holyhead

There are 50 primary schools in Anglesey, all co-educational day schools.[49]

Transport

Anglesey is linked to the mainland by the Britannia Bridge, which carries the A55 from Holyhead, and the Menai Suspension Bridge, which carries the A5. The A5025 round the northern edge of Anglesey and the A4080 round the southern edge form a ring.

Anglesey's six railway stations are Holyhead, Valley, Rhosneigr, Ty Croes, Bodorgan and Llanfairpwll. All are on the North Wales Coast Line, with services operated by Avanti West Coast to London Euston, and by Transport for Wales Rail to Chester, Manchester Piccadilly, Birmingham New Street and Cardiff Central. Historically the island was also served by the Anglesey Central Railway which ran from Gaerwen to Amlwch, and the Red Wharf Bay branch line between the Holland Arms railway station and Red Wharf Bay.

By air, Anglesey Airport has a twice-daily scheduled service to Cardiff Airport, where connections worldwide can be made.

The ferry port of Holyhead handles more than 2 million passengers each year. Stena Line and Irish Ferries sail to Dublin and previously to Dún Laoghaire in Ireland, forming the principal link for surface transport from central and northern England and Wales to Ireland.

Sport and leisure

Anglesey is independently represented in the Island Games (under its Welsh name Ynys Môn). The team finished joint 17th in the 2009 Games hosted by Åland,[50] winning medals in gymnastics, sailing and shooting.[51]

Anglesey made an unsuccessful bid to host the 2009 games, led by Ynys Môn MP Albert Owen. The island expected to benefit from more than £3m of spending if it had hosted the event. However, Anglesey currently lacks two facilities necessary for a successful bid: a six-lane competition swimming pool and an athletics track.[52]

Several precursors to the modern football codes were highly popular in Anglesey. They had few rules, and were quite violent. Rhys Cox, at the turn of the 18th century, described a game in Llandrygan as ending with "numbers of players... left here and there on the road, some having limbs broken in the struggle, others severely injured, and some carried on biers to be buried in the churchyard nearest to where they had been mortally injured." William Bulkeley, in his April 1734 diary, records that the violence of such games left no hard feelings, with both sides parting "as good friends as they came, after they had spent half an hour together cherishing their spirits with a cup of ale... having finished Easter Holydays innocently and merrily."[53]

Association football

Football arrived on the island in the 1870s. It was initially met with resistance, given its locally perceived associations with drunkenness and rowdiness, and the lower classes. One critic dismissed it as "un-Christian practice". The Anglesey League, comprising teams from Amlwch, Beaumaris, Holyhead, Menai Bridge, Llandegfan, and Llangefni, was, however, formed in the 1895–1896 football season.[54]

The Ynys Môn football team represent the island of Anglesey at the biannual Island Games, winning gold in 1999. In 2018, the island was chosen to host the 2019 Inter Games Football Tournament, where the men's team won gold and the women's team won silver.

For the 2019–2020 season, Llangefni Town is playing in the Cymru North league – in the second tier of the Welsh football league system, after winning the Welsh Alliance League title the previous season.

There are seven Anglesey clubs playing in the Welsh Alliance, including Bodedern Athletic and Holyhead Hotspur in Division One. Local clubs also participate in the Gwynedd League and the Anglesey League.

Rugby Union

Llangefni RFC is the island's highest competing team in the WRU Division One North.

Llangoed hosts an annual rugby sevens contest. Touring sides have included Manhattan RFC.

Anglesey Hunt

The Anglesey Hunt, formed in 1757, was the second oldest fox hunting association in Wales (the oldest being the Tivyside Hunt in Cardiganshire).[55]

Athletics

Every September the Anglesey Festival of Running takes place. It includes a marathon, a half-marathon, 10-km and 5–km races, and children's contests. Its slogan is Run the Island.

Motorsport

The Anglesey Circuit (Welsh: Trac Môn) is a fully licensed MSA and ACU championship racing circuit that opened in 1997.

Cricket

The Beaumaris Cricket Club was formed in 1858. Clubs at Holyhead, Amlwch and Llangefni were formed within the following decade, but it was not until the 1880s that the sport became popular outside the upper classes. Bodedern Cricket Club was formed in 1947.[54]

Sailing

The Royal Anglesey Yacht Club hosts the Menai Strait Regatta yearly.

Swimming

The Menai Strait hosts two annual open-water swimming contests: the Menai Strait Swim from Foel to Caernarfon (1 mile), and the Pier to Pier Open Water Swim, between Beaumaris and Garth Pier, Bangor.

See also

- Roman conquest of Anglesey

- List of Scheduled Monuments in Anglesey

- List of places in Anglesey

- List of Anglesey towns by population

- List of Lord Lieutenants of Anglesey

- List of Custos Rotulorums of Anglesey

- List of Sheriffs of Anglesey

- Isle of Anglesey County Council

- Ynys Môn (UK Parliament constituency)

- Ynys Môn (Assembly constituency)

- List of islands of Wales – including those around Anglesey

- The Royal Navy's four ships named HMS Anglesea

- HMS Anglesey (P277)

Notes

- "Sir Ynys Mon – Isle of Anglesey". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- "Anglesey Nature introduction". Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- "Local Authority population 2011". Archived from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- C. Michael Hogan (2011). "Irish Sea". In P. Saundry; C. Cleveland (eds.). Encyclopedia of Earth. Washington, D. C.: National Council for Science and the Environment.

- National Archives of the United Kingdom. Local Government (Wales) Act 1994, Schedule 1: The New Principal Areas. Accessed 6 February 2013.

- "Background Paper 10B: Anglesey Language Profile" (PDF). Gwynedd Council. February 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- Lena Peterson, et al. Nordiskt runnamnslexikon Archived 2011-08-26 at WebCite (Dictionary of Names from Runic Inscriptions), p. 116, May 2001. Accessed 6 June 2012.

- Room, Adrian. Placenames of the World, p. 30. McFarland, 2003. Accessed 6 February 2013.

- Warren Kovach Anglesey, Wales. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- Davies, John. A History of Wales, pp. 98–99.

- Chisholm 1911, pp. 17–18.

- The London Encyclopaedia. "Anglesey". Tegg (London), 1839. Accessed 6 February 2013.

- University of Texas at Austin's Linguistics Research Center.Proto-Indo-European Etyma 9.14 Archived March 8, 2014, at the Wayback Machine: Physical Acts & Materials: to Bend". 17 May 2011. Accessed 6 February 2013.

- Tacitus. Annals, XIV.29. and Agricola, XIV.14 & 18. Accessed 6 April 2013.

- Pliny. Natural History, IV.30. Accessed 6 April 2013.

- Cassius Dio. Roman History, 62.

- The Present State of the British Empire in Europe, America, Africa, and Asia. Wales. Anglesea. Griffith (London), 1768.

- Davies, Edward. The Mythology and Rites of the British Druids, p. 177. Booth (London), 1809. Accessed 6 February 2013.

- Tacitus Agricola 18.3–5.

- Chisholm, Hugh (1910). The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information. Encyclopædia Britannica Company. p. 18.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ptolemy, Geog., Bk. 2, Ch. 1 & 2

- Stanley, Anglesey, 1871, and many Celtic contributions, especially on Celtic subjects, to Archaeologia Cambrensis.

- Devine, Darren (2012-02-15). "Anglesey during the First World War and Second World War". walesonline. Retrieved 2018-03-05.

- A Years' Work of the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, Annual Report for 1936-1937, adopted by the Council and Corporation, May 28, 1937, London, p. 12.

- Davies, John; Jenkins, Nigel; Baines, Menna; Llynch, Peredur (2008). The Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 494. ISBN 978-0-7083-1953-6.

- "First Welsh olive grove planted on Anglesey". WalesOnline. 30 April 2007. Retrieved 2013-05-09.

- "40 years of outstanding natural beauty". Welsh Government. 13 December 2007. Archived from the original on 24 September 2006. Retrieved 2013-05-09.

- "Visit Anglesey – Home". Visit Anglesey. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- Damian Carrington. "Renewables industry welcomes reduced subsidies for onshore windfarms". the Guardian. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- Anglesey protest over plans for new nuclear power plant BBC News, 30 March 2014

- "Hitachi's Wylfa nuclear project pause 'tremendous blow'". BBC News. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- Anglesey Today: Energy accessed 15 April 2014

- SeaGen Wales accessed 15 April 2014

- Energy Island Programme Archived 2014-02-22 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 15 April 2014.

-

- C. Michael Hogan. 2009. Marsh Thistle: Cirsium palustre, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed. N. Strömberg Archived 2012-12-13 at the Wayback Machine

- "Home – Squirrels Map". Squirrels Map. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- "Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty". Pixaerial: North Wales from the Air. Archived from the original on February 18, 2007. Retrieved February 21, 2006.

- Vaughan, Adam (17 January 2019). "Hitachi scraps £16bn nuclear power station in Wales" – via www.theguardian.com.

- Hitachi-Horizon Nuclear Power Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- Vaughan, Adam (9 April 2018). "Plans for Welsh nuclear power plant delayed by concerns over seabirds" – via www.theguardian.com.

- "UK and Japan look at public finance for Wylfa nuclear plant". Financial Times.

- BBC One site. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- "Language spoken in Wales, 1911". www.histpop.org. p. iv. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- "Welsh Language and Culture - Gwynedd Council report" (PDF). gwynedd.gov.uk.

- "Linguistic progression and standards of Welsh in ten bilingual schools - November 2014 - Estyn". www.estyn.gov.wales. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- "Ysgol Uwchradd Bodedern Estyn Report 2014" (PDF). Estyn. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- "GeoMôn – Anglesey Geopark". Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- "Stone Science Museum - Fossils & Dinosaurs - Anglesey North Wales". Stone Science Museum Anglesey.

- Isle of Anglesey County Council, Serving Anglesey Archived May 24, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "NatWest Island Games XIII – Medal Table". Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- "NatWest Island Games XIII – Ynys Môn Medal Winners". Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- Clark, Rhodri. "Out of the running for island 'Olympics'". Western Mail. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ETBRS (2005b).

- Pretty (2005).

- ETBRS (2005a).

References

- Lile, Emma (2005). "Fox Hunting (Wales)". In Collins, Tony; Martin, John; Vamplew, Wray (eds.). Encyclopedia of Traditional British Rural Sports. Sports Reference series. Routledge. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-415-35224-6..

- Lile, Emma (2005), "Football (Wales)", in Collins, Tony; Martin, John; Vamplew, Wray (eds.), Encyclopedia of Traditional British Rural Sports, Sports Reference series, Routledge, pp. 120–121, ISBN 978-0-415-35224-6.

- Pretty, David A. (2005), Anglesey: The Concise History, Vol. 1, Histories of Wales, University of Wales Press, p. 111, ISBN 978-0708319437

Attribution:

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anglesey. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Anglesey. |

- Isle of Anglesey at Curlie