Transylvania

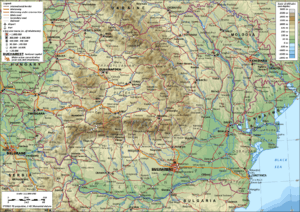

Transylvania is a historical region that is located in central Romania. Bound on the east and south by its natural borders, the Carpathian mountain range, historical Transylvania extended westward to the Apuseni Mountains. The term sometimes encompasses not only Transylvania proper, but also parts of the historical regions of Crișana and Maramureș, and occasionally the Romanian part of Banat.

Transylvania | |

|---|---|

| |

.svg.png) Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Nickname(s): "The Land Beyond the Forest" | |

| |

| Coordinates: 46°46′0″N 23°35′0″E | |

| Country | |

| Largest city | Cluj-Napoca |

| Area | |

| • Total | 102,834 km2 (39,704 sq mi) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 6,789,250 |

| • Density | 66/km2 (170/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Transylvanian |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

The region of Transylvania is known for the scenery of its Carpathian landscape and its rich history. It also contains major cities such as Cluj-Napoca, Brașov, Sibiu, Târgu Mureș, Alba Iulia, and Bistrița.

The Western world commonly associates Transylvania with vampires, thanks to the influence of Bram Stoker's novel Dracula and the many films the tale inspired.[1][2]

Etymology

The earliest known reference to Transylvania appears in a Medieval Latin document of the Kingdom of Hungary in 1075 as ultra silvam, meaning "beyond the forest" (ultra meaning "beyond" or "on the far side of" and the accusative case of sylva (sylvam) "woods, forest"). Transylvania, with an alternative Latin prepositional prefix, means "on the other side of the woods". Hungarian historians claim that the Medieval Latin form Ultrasylvania, later Transsylvania, was a direct translation from the Hungarian form Erdő-elve.[3] That also was used as an alternative name in German überwald (13th–14th centuries) and Ukrainian Залісся (Zalissia). Historical names of Transylvania are:

- Bulgarian: Седмиградско, romanized: Sedmigradsko, Трансилвания Transilvanija

- Croatian: Sedmogradska, Erdelj (hist.), Transilvanija

- German: Siebenbürgen, Transsilvanien

- Hungarian: Erdély

- Latin: Ultrasilvania, Transsilvania

- Polish: Siedmiogród, Transylwania

- Romani: Transilvaniya

- Romanian: Ardeal, Transilvania

- Russian: Ардял, romanized: Ardyal, Трансильвания Transil'vaniya

- Serbian: Ердељ/Erdelj, Serbian: Трансилванија/Transilvanija

- Slovak: Sedmohradsko

- Transylvanian Saxon: Siweberjen

- Turkish: Erdel, Transilvanya

- Ukrainian: Семигород, romanized: Semyhorod, Залісся Zalissiya, Трансильванія Transyl'vaniya

- Yiddish: זיבנבערגן, romanized: Zibnbergn, זימבערגן Zimbergn, טראַנסילוואַניע Transilvanye

In Romanian, the region is known as Ardeal (pronounced [arˈde̯al]) or Transilvania [transilˈvani.a]; in Hungarian as Erdély [ˈɛrdeːj]; in German as Siebenbürgen [ˈziːbn̩ˌbʏʁɡn̩] (![]()

- The German name Siebenbürgen means "seven castles", after the seven (ethnic German) Transylvanian Saxons' cities in the region. This is also the origin of the region's name in many other languages, such as the Croatian Sedmogradska, the Bulgarian Седмиградско (Sedmigradsko), Polish Siedmiogród, Yiddish זיבנבערגן (Zibnbergn), and the Ukrainian Семигород (Semyhorod).

- The Hungarian form Erdély was first mentioned in the 12th-century Gesta Hungarorum as Erdeuleu (in modern script Erdeüleü) or Erdő-elve. The word Erdő means forest in Hungarian, and the word Elve denotes a region in connection with this, similarly to the Hungarian name for Muntenia (Havas-elve, or land lying ahead of the snow-capped mountains). Erdel, Erdil, Erdelistan, the Turkish equivalents, or the Romanian Ardeal were borrowed from this form as well.

- The first known written occurrence of the Romanian name Ardeal appeared in a document in 1432 as Ardeliu. The Romanian Ardeal is derived from the Hungarian Erdély.[4]

History

Transylvania has been dominated by several different peoples and countries throughout its history. It was once the nucleus of the Kingdom of Dacia (82 BC – 106 AD). In 106 AD the Roman Empire conquered the territory, systematically exploiting its resources. After the Roman legions withdrew in 271 AD, it was overrun by a succession of various tribes, bringing it under the control of the Carpi, Visigoths, Huns, Gepids, Avars, and Slavs. From 9th to 11th century Bulgarians ruled Transylvania.[5] It is a subject of dispute whether elements of the mixed Daco–Roman population survived in Transylvania through the Post-classical Era (becoming the ancestors of modern Romanians) or the first Vlachs/Romanians appeared in the area in the 13th century after a northward migration from the Balkan Peninsula.[6][7] There is an ongoing scholarly debate over the ethnicity of Transylvania's population before the Hungarian conquest (see Origin of the Romanians).

The Magyars conquered much of Central Europe at the end of the 9th century. According to Gesta Hungarorum, the Vlach voivode Gelou ruled Transylvania before the Hungarians arrived. The Kingdom of Hungary established partial control over Transylvania in 1003, when king Stephen I, according to legend, defeated the prince named Gyula.[8][9][10][11] Some historians assert Transylvania was settled by Hungarians in several stages between the 10th and 13th centuries,[12][13] while others claim that it was already settled,[14] since the earliest Hungarian artifacts found in the region are dated to the first half of the 10th century.[15] After the Battle of Kosovo and Ottoman arrival at the Hungarian border, thousands of Vlach and Serbian refugees came to Transylvania.[16]

Between 1003 and 1526, Transylvania was a voivodeship in the Kingdom of Hungary, led by a voivode appointed by the King of Hungary.[17][18] After the Battle of Mohács in 1526, Transylvania became part of the Kingdom of János Szapolyai. Later, in 1570, the kingdom transformed into the Principality of Transylvania, which was ruled primarily by Calvinist Hungarian princes. During that time, the ethnic composition of Transylvania was estimated in Antun Vrančić's work,[note 1] but according to how the original text was translated by Romanian or Hungarian scholars, there are two different variants of interpretations. According to the Romanian interpretations, Antun Vrančić wrote that Transylvania "is inhabited by three nations – Székelys, Hungarians and Saxons; I should also add the Romanians who – even though they easily equal the others in number – have no liberties, no nobility and no rights of their own, except for a small number living in the District of Hátszeg, where it is believed that the capital of Decebalus lay, and who were made nobles during the time of John Hunyadi, a native of that place, because they always took part tirelessly in the battles against the Turks",[19] while according to the Hungarian interpretations the translation of the first part of the sentence would be "...I should also add the Romanians who – even though they easily equal any of the others in number...".[20] In 1650, Vasile Lupu wrote in a letter to the Sultan that the Romanians already numbered more than one-third of the population of Transylvania.[21] For most of this period, Transylvania, maintaining its internal autonomy, was under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire.

The Habsburgs acquired the territory shortly after the Battle of Vienna in 1683. In 1687, the rulers of Transylvania recognized the suzerainty of the Habsburg emperor Leopold I, and the region was officially attached to the Habsburg Empire. The Habsburgs acknowledged Principality of Transylvania as one of the Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen,[22] but the territory of principality was administratively separated[23][24] from Habsburg Hungary[25][26][27] and subjected to the direct rule of the emperor's governors.[28] In 1699 the Turks legally acknowledged their loss of Transylvania in the Treaty of Karlowitz; however, some anti-Habsburg elements within the principality submitted to the emperor only in the 1711 Peace of Szatmár, and Habsburg control over Principality of Transylvania was consolidated. The Grand Principality of Transylvania was reintroduced 54 years later in 1765.

The Hungarian revolution against the Habsburgs started in 1848. The revolution in the Kingdom of Hungary grew into a war for the total independence from the Habsburg dynasty. Julius Jacob von Haynau, the leader of the Austrian army was appointed plenipotentiary to restore order in Hungary after the conflict. He ordered the execution of The 13 Hungarian Martyrs of Arad and Prime Minister Batthyány was executed the same day in Pest. After a series of serious Austrian defeats in 1849, the empire came close to the brink of collapse. Thus, the new young emperor Franz Joseph I had to call for Russian help in the name of the Holy Alliance. Czar Nicholas, I answered, and sent 200,000 men strong army with 80,000 auxiliary forces. Finally, the joint army of Russian and Austrian forces defeated the Hungarian forces. After the restoration of Habsburg power, Hungary was placed under martial law. Following the Hungarian Army's surrender at Világos (now Șiria, Romania) in 1849, their revolutionary banners were taken to Russia by the Tsarist troops and were kept there both under the Tsarist and Communist systems (in 1940 the Soviet Union offered the banners to the Horthy government).

After the Ausgleich of 1867, the Principality of Transylvania was once again abolished. The territory then became part of Transleithania,[9][11] an addition to the newly established Austro-Hungarian Empire. Romanian intellectuals issued the Blaj Pronouncement in protest.[29]

The region was the site of an important battle during World War I, which caused the replacement of the German Chief of Staff, temporarily ceased German offensives on all the other fronts and created a unified Central Powers command under the German Kaiser. Following defeat in World War I, Austria-Hungary disintegrated. Elected representatives of the ethnic Romanians from Transylvania, Banat, Crişana and Maramureş backed by the mobilization of Romanian troops, proclaimed Union with Romania on 1 December 1918. The Proclamation of Union of Alba Iulia was adopted by the Deputies of the Romanians from Transylvania and supported one month later by the vote of the Deputies of the Saxons from Transylvania.

The national holiday of Romania, the Great Union Day (also called Unification Day[30]) occurring on December 1, celebrates this event. The holiday was established after the Romanian Revolution, and marks the unification not only of Transylvania but also of the provinces of Banat, Bessarabia and Bukovina with the Romanian Kingdom. These other provinces had all joined with the Kingdom of Romania a few months earlier. In 1920, the Treaty of Trianon established new borders, much of the proclaimed territories became part of Romania. Hungary protested against the new state borders, as they did not follow the real ethnic boundaries, for over 1.3 or 1.6 million Hungarian people, representing 25.5 or 31.6% of the Transylvanian population (depending on statistics used),[31][32] were living on the Romanian side of the border, mainly in the Székely Land of Eastern Transylvania, and along the newly created border.

In August 1940, by the Second Vienna Award, with the arbitration of Germany and Italy, Hungary gained Northern Transylvania (including parts of Crișana and Maramureș) totaling over 40% of the territory lost in 1920. This award did not solve the nationality problem, as over 1.15–1.3 million Romanians (or 48% to more than 50% of the population of the ceded territory) remained in Northern Transylvania while 0.36–0.8 million Hungarians (or 11% to more than 20% of the population) continued to reside in Southern Transylvania.[33] The Second Vienna Award was voided on 12 September 1944 by the Allied Commission through the Armistice Agreement with Romania (Article 19); and the 1947 Treaty of Paris reaffirmed the borders between Romania and Hungary, as originally defined in the Treaty of Trianon, 27 years earlier, thus confirming the return of Northern Transylvania to Romania.[9]

From 1947 to 1989, Transylvania, along with the rest of Romania, was under a communist regime. The ethnic clashes of Târgu Mureș occurred between ethnic Romanians and Hungarians in March 1990 after the fall of the communist regime and became the most notable inter-ethnic incident in the post-communist era.

- Ruins of Sarmizegetusa Regia

Roman city of Apulum

Roman city of Apulum A market scene in Transylvania, 1818

A market scene in Transylvania, 1818 The National Assembly in Alba Iulia (December 1, 1918), declaring the Union of Transylvania with Romania

The National Assembly in Alba Iulia (December 1, 1918), declaring the Union of Transylvania with Romania

Geography and ethnography

The Transylvanian Plateau, 300 to 500 metres (980–1,640 feet) high, is drained by the Mureș, Someș, Criș, and Olt rivers, as well as other tributaries of the Danube. This core of historical Transylvania roughly corresponds with nine counties of modern Romania. The plateau is almost entirely surrounded by the Eastern, Southern and Romanian Western branches of the Carpathian Mountains. The area includes the Transylvanian Plain. Other areas to the west and north are widely considered part of Transylvania. In common reference, the Western border of Transylvania has come to be identified with the present Romanian-Hungarian border, settled in the 1920 Treaty of Trianon, though geographically the two are not identical.

Ethnographic areas:

- Transylvania proper:

- Mărginimea Sibiului (Szeben-hegyalja)

- Transylvanian Plain (Câmpia Transilvaniei/Mezőség)

- Țara Bârsei (Burzenland/Barcaság)

- Țara Buzaielor

- Țara Călatei (Kalotaszeg)

- Țara Chioarului (Kővár)

- Țara Făgărașului (Fogaras)

- Țara Hațegului (Hátszeg)

- Țara Hălmagiului

- Țara Mocanilor

- Țara Moților

- Țara Năsăudului (Nösnerland/Naszód vidéke)

- Țara Silvaniei

- Ținutul Pădurenilor

- Ținutul Secuiesc (Székely Land)

- Banat

- Țara Almăjului

- Crișana

- Țara Zarandului

- Maramureș

- Țara Oașului (Avasság)

- Țara Lăpușului (Lápos-vidék)

Administrative divisions

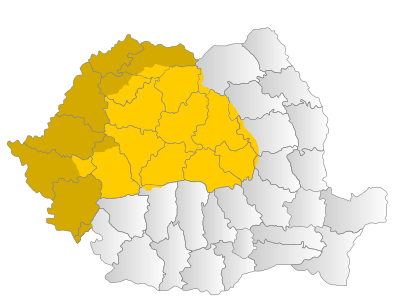

Light yellow – historical region of Transylvania

Dark yellow – historical regions of Banat, Crișana and Maramureș

Grey – historical regions of Wallachia, Moldavia and Dobruja

The area of the historical Voivodeship is 55,146 km2 (21,292 sq mi).[34][35]

The regions granted to Romania in 1920 covered 23 counties including nearly 102,200 km2 (39,460 sq mi) (102,787–103,093 km2 in Hungarian sources and 102,200 km2 in contemporary Romanian documents). Nowadays, due to the several administrative reorganisations, the territory covers 16 counties (Romanian: judeţ), with an area of 100,290 km2 (38,722 sq mi), in central and northwest Romania.

The 16 counties are: Alba, Arad, Bihor, Bistriţa-Năsăud, Brașov, Caraș-Severin, Cluj, Covasna, Harghita, Hunedoara, Maramureș, Mureș, Sălaj, Satu Mare, Sibiu, and Timiș.

Transylvania contains both largely urban counties, such as Brașov and Hunedoara counties, as well as largely rural ones, such as Bistriţa-Năsăud and Sălaj counties.[36]

Since 1998, Romania has been divided into eight development regions, acting as divisions that coordinate and implement socio-economic development at regional level. Six counties (Alba, Brașov, Covasna, Harghita, Mureș and Sibiu) form the Centru development region, other six counties (Bihor, Bistrița-Năsăud, Cluj, Maramureș, Satu Mare, Sălaj) form the Nord-Vest development region, while four (Arad, Caraș-Severin, Hunedoara, Timiș) form the Vest development region.

Cities

The most populous cities as of 2011 census[37] (metropolitan areas, as of 2014[38]):

- Transylvania proper:

- Cluj-Napoca – 324,576 (375,251 in metropolitan area)

- Brașov – 253,200 (398,462)

- Sibiu – 147,245 (208,894)

- Târgu Mureș – 134,290 (181,162)

- Alba Iulia – 63,536 (109,484)

- Banat:

- Crișana:

- Maramureș:

Cluj-Napoca, commonly known as Cluj, is the second most populous city in Romania, after the national capital Bucharest, and the seat of Cluj County. From 1790 to 1848 and from 1861 to 1867, it was the official capital of the Grand Principality of Transylvania. Brașov is an important tourist destination, being the largest city in a mountain resorts area, and a central location, suitable for exploring Romania, with the distances to several tourist destinations (including the Black Sea resorts, the monasteries in northern Moldavia, and the wooden churches of Maramureș) being similar.

Sibiu is one of the most important cultural centres of Romania and was designated the European Capital of Culture for the year 2007, along with the city of Luxembourg,[39] and it was formerly the centre of the Transylvanian Saxon culture and between 1692 and 1791 and 1849–65 was the capital of the Principality of Transylvania.

Alba Iulia is a city located on the Mureş River in Alba County, and since the High Middle Ages, the city has been the seat of Transylvania's Roman Catholic diocese. Between 1541 and 1690 it was the capital of the Eastern Hungarian Kingdom and the latter Principality of Transylvania. Alba Iulia also has historical importance because at the end of World War I, representatives of the Romanian population of Transylvania gathered in Alba Iulia on 1 December 1918 to proclaim the union of Transylvania with the Kingdom of Romania. In Transylvania, there are many medieval smaller towns such as Sighișoara, Mediaș, Sebeș, and Bistrița.

Population

Historical population

Official censuses with information on Transylvania's population have been conducted since the 18th century. On May 1, 1784 the Emperor Joseph II called for the first official census of the Habsburg Empire, including Transylvania. The data was published in 1787, and this census showed only the overall population (1,440,986 inhabitants).[40] Fényes Elek, a 19th-century Hungarian statistician, estimated in 1842 that in the population of Transylvania for the years 1830–1840 the majority were 62.3% Romanians and 23.3% Hungarians.[41]

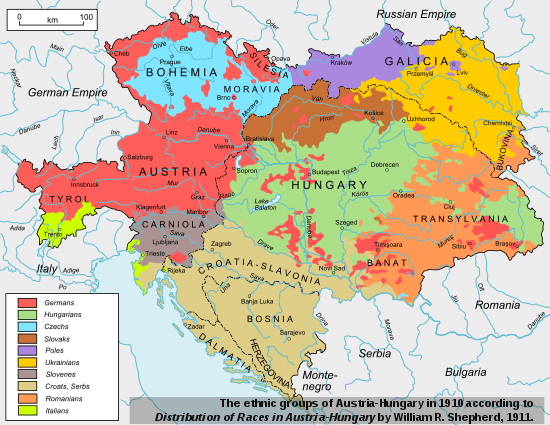

In the last quarter of the 19th century, the Hungarian population of Transylvania increased from 24.9% in 1869 to 31.6%, as indicated in the 1910 Hungarian census (the majority of the Jewish population reported Hungarian as their primary language, so they were also counted as ethnically Hungarian in the 1910 census). At the same time, the percentage of the Romanian population decreased from 59.0% to 53.8% and the percentage of the German population decreased from 11.9% to 10.7%, for a total population of 5,262,495. Magyarization policies greatly contributed to this shift.[42]

The percentage of the Romanian majority has significantly increased since the declaration of the union of Transylvania with Romania after World War I in 1918. The proportion of Hungarians in Transylvania was in steep decline as more of the region's inhabitants moved into urban areas, where the pressure to assimilate and Romanianize was greater.[32] The expropriation of the estates of Magyar magnates, the distribution of the lands to the Romanian peasants, and the policy of cultural Romanianization that followed the Treaty of Trianon were major causes of friction between Hungary and Romania.[43] Other factors include the emigration of non-Romanian peoples, assimilation and internal migration within Romania (estimates show that between 1945 and 1977, some 630,000 people moved from the Old Kingdom to Transylvania, and 280,000 from Transylvania to the Old Kingdom, most notably to Bucharest).[32]

Current population

According to the results of the 2011 Population Census, the total population of Transylvania was 6,789,250 inhabitants and the ethnic groups were: Romanians – 70.62%, Hungarians – 17.92%, Roma – 3.99%, Ukrainians – 0.63%, Germans – 0.49%, other – 0.77%. Some 378,298 inhabitants (5.58%) have not declared their ethnicity. The presented data are from http://www.recensamantromania.ro/rezultate-2, Table no. 7. The ethnic Hungarian population of Transylvania form a majority in the counties of Covasna (73.6%) and Harghita (84.8%). The Hungarians are also numerous in the following counties: Mureș (37.8%), Satu Mare (34.5%), Bihor (25.2%), and Sălaj (23.2%).

Economy

Transylvania is rich in mineral resources, notably lignite, iron, lead, manganese, gold, copper, natural gas, salt, and sulfur.

There are large iron and steel, chemical, and textile industries. Stock raising, agriculture, wine production and fruit growing are important occupations. Agriculture is widespread in the Transylvanian Plateau, including growing cereals, vegetables, viticulture and breeding cattle, sheep, swine, and poultry. Timber is another valuable resource.

IT, electronics and automotive industries are important in urban and university centers like Cluj-Napoca (Robert Bosch GmbH, Emerson Electric), Timișoara (Alcatel-Lucent, Flextronics and Continental AG), Brașov, Sibiu, Oradea and Arad. The cities of Cluj Napoca and Târgu Mureș are connected with a strong medical tradition, and according to the same classifications top performance hospitals exist there.[44]

Native brands include: Roman of Brașov (trucks and buses), Azomureș of Târgu Mureș (fertilizers), Terapia of Cluj-Napoca (pharmaceuticals), Banca Transilvania of Cluj-Napoca (finance), Romgaz and Transgaz of Mediaș (natural gas), Jidvei of Alba county (alcoholic beverages), Timișoreana of Timișoara (alcoholic beverages) and others.

The Jiu Valley, located in the south of Hunedoara County, has been a major mining area throughout the second half of the 19th century and the 20th century, but many mines were closed down in the years following the collapse of the communist regime, forcing the region to diversify its economy.

During the Second World War, Transylvania (the Southern/Romanian half, as the region was divided during the war) was crucial to the Romanian defense industry. Transylvanian factories built until 1945 over 1,000 warplanes and over 1,000 artillery pieces of all types, among others.[45]

Culture

The culture of Transylvania is complex, due to its varied history and multiculturalism. Its culture has been historically linked to both Central Europe and Southeastern Europe; and it has significant Hungarian (see Hungarians in Romania) and German (see Germans of Romania) influences.[46]

With regard to architecture, the Transylvanian Gothic style is preserved to this day in monuments such as the Black Church in Braşov (14th and 15th centuries) and a number of other cathedrals, as well as the Bran Castle in Braşov County (14th century), the Hunyad Castle in Hunedoara (15th century).

Notable writers such as Emil Cioran, Lucian Blaga, George Coșbuc, Octavian Goga and Liviu Rebreanu were born in Transylvania. The latter wrote the novel Ion, which introduces the reader to a depiction of the life of the peasants and intellectuals of Transylvania at the turn of the 20th century.

Religion

Transylvania has a very rich and unique religious history from the other regions of Europe. Since the Protestant Reformation, different Christian denominations have been coexisting in this religious melting pot, including Romanian Orthodox, Romanian Greek Catholic, other Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, Lutheran, Reformed, and Unitarian branches. Other faiths also are present, including Jews and Muslims. Under the Habsburgs, Transylvania served as a place for "religious undesirables". People who arrived in Transylvania included those that did not conform to the Catholic Church and were sent here forcibly, as well as many religious refugees. Transylvania has a long history of religious tolerance. This has been ensured by its religious pluralism. Christianity is the largest religion in Transylvania. Transylvania has also been (and still is) a center for Christian denominations other than Eastern Orthodoxy, the form of Christianity that most Romanians follow. As such, there are significant numbers of inhabitants of Transylvania that follow Roman Catholicism, Greek Catholicism and Protestantism.[47]

| 1930 | 2011 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denomination | Number | Percent | Number | Percent |

| Eastern Orthodoxy | 1,933,589 | 34.85 | 4,478,532 | 65.96 |

| Greek Catholicism | 1,385,017 | 24.96 | 142,862 | 2.10 |

| Roman Catholicism | 946,100 | 17.05 | 632,948 | 9.32 |

| Mainline Protestantism | 1,038,464 | 18.72 | 675,107 | 9.34 |

| Evangelical Protestantism | 37,061 | 0.66 | 339,472 | 4.70 |

There are also small denominations like adventism, Jehovah's Witnesses and more.

Others

- Nowadays, there is a very small number of Muslims (Islam) and Jews (Judaism), but back in 1930, with 191,877 inhabitants, Jews represented 3.46% of Transylvania's population.[48]

- Atheists, agnostics and unaffiliated account for 0.27% of Transylvania's population.

Data refers to extended Transylvania (with Banat, Crișana and Maramureș).[49][50]

Tourist attractions

- Bran Castle, also known as Dracula's Castle

- The medieval cities of Alba Iulia, Cluj-Napoca (European Youth Capital 2015), Sibiu (European Capital Of Culture in 2007), Târgu Mureș and Sighișoara (UNESCO World Heritage Site and alleged birthplace of Vlad Dracula)

- The city of Brașov and the nearby Poiana Brașov ski resort

- The city of Hunedoara with the 14th century Corvin Castle

- The citadel and the Art Nouveau city centre of Oradea

- The Densuș Church, the oldest church in Romania that still holds services[51]

- The Dacian Fortresses of the Orăştie Mountains, including Sarmizegetusa Regia (UNESCO World Heritage Site)

- The Roman forts including Sarmizegetusa Ulpia Traiana, Porolissum, Apulum, Potaissa and Drobeta

- The Red Lake (also known as Lake Ghilcoş)

- The Turda Gorge natural reserve

- The Râșnov Citadel in Râșnov

- The Maramureș region

- The Merry Cemetery of Săpânța (the only one of that kind in the world)

- The Wooden Churches (UNESCO World Heritage Site)

- The cities of Baia Mare and Sighetu Marmației

- The villages in the Iza, Mara, and Viseu valleys

- The Saxon fortified churches (UNESCO World Heritage Site)

- The Apuseni Mountains:

- Țara Moților

- The Bears Cave[52]

- Scărișoara Cave in Alba County, the third largest glacier cave in the world[52]

- The Rodna Mountains

- The Salina Turda Salt Mine: according to Business Insider—one of the ten "coolest underground places in the world".

Festivals and events

Film festivals

- Transilvania International Film Festival, Cluj-Napoca – Romania's biggest film festival

- Gay Film Nights, Cluj-Napoca

- Comedy Cluj, Cluj-Napoca

- Humor Film Festival, Timișoara [53][54]

Music festivals

- Golden Stag Festival, Brașov

- Gărâna Jazz Festival, Gărâna

- Peninsula / Félsziget Festival, Târgu-Mureș

- Untold Festival, Cluj-Napoca – Romania's biggest music festival

- Toamna Muzicală Clujeană, Cluj-Napoca

- Artmania Festival, Sibiu

- Rockstadt Extreme Fest, Râșnov

- Electric Castle Festival, Bontida, Cluj-Napoca

Others

- Sighișoara Medieval Festival, Sighișoara

- Sibiu International Theatre Festival

- Festivalul Medieval Cetăți Transilvane Sibiu

Historical coat of arms of Transylvania

The first heraldic representations of Transylvania date from the 16th century. One of the predominant early symbols of Transylvania was the coat of arms of Sibiu city. In 1596 Levinus Hulsius created a coat of arms for the imperial province of Transylvania, consisting of a shield party per fess, with a rising eagle in the upper field and seven hills with towers on top in the lower field. He published it in his work "Chronologia", issued in Nuremberg the same year. The seal from 1597 of Sigismund Báthory, prince of Transylvania, reproduced the new coat of arms with some slight changes: in the upper field the eagle was flanked by a sun and a moon and in the lower field the hills were replaced by simple towers.[55]

The seal of Michael the Brave from 1600 depicts the territory of the former Dacian kingdom: Wallachia, Moldavia and Transylvania:[56]

- The black eagle (Wallachia)

- The aurochs head (Moldavia)

- The seven hills (Transylvania).

- Over the hills there were two rampant lions affronts, supporting the trunk of a tree, as a symbol of the reunited Dacian Kingdom.[56]

The Diet of 1659 codified the representation of the privileged nations in Transylvania's coat of arms. It depicted a black turul on a blue background, representing the Hungarian nobility,[57] a Sun and the Moon representing the Székelys, and seven red towers on a yellow background representing the seven fortified cities of the Transylvanian Saxons. The red dividing band was originally not part of the coat of arms.

In popular culture

Following the publication of Emily Gerard's The Land Beyond the Forest (1888), Bram Stoker wrote his gothic horror novel Dracula in 1897, using Transylvania as a setting. With its success, Transylvania became associated in the English-speaking world with vampires. Since then it has been represented in fiction and literature as a land of mystery and magic. For example, in Paulo Coelho's novel The Witch of Portobello, the main character, Sherine Khalil, is described as a Transylvanian orphan with a Romani mother, in an effort to add to the character's exotic mystique. The so-called Transylvanian trilogy of historical novels by Miklós Bánffy, The Writing on the Wall, is an extended treatment of the 19th- and early 20th-century social and political history of the country. Among the first actors to portray Dracula in film was Bela Lugosi, who was born in Lugos (now Lugoj), in present-day Romania.

Notes

- Antonius Wrancius: Expeditionis Solymani in Moldaviam et Transsylvaniam libri duo. De situ Transsylvaniae, Moldaviae et Transalpinae liber tertius.

References

- "Travel Advisory; Lure of Dracula In Transylvania". The New York Times. 1993-08-22.

- "Romania Transylvania". Icromania.com. 2007-04-15. Retrieved 2012-07-30.

- Engel, Pál (2001). Realm of St. Stephen: History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526 (International Library of Historical Studies), page 24, London: I.B. Taurus. ISBN 1-86064-061-3

- Pascu, Ștefan (1972). "Voievodatul Transilvaniei". I: 22. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "6. SOUTHERN TRANSYLVANIA UNDER BULGAR RULE". mek.oszk.hu. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- István Lázár: Transylvania, a Short History, Simon Publications, Safety Harbor, Florida, 1996 + It was the nucleus of the Kingdom of Dacia (82 BC – 106 AD). In 106 AD the Roman Empire conquered the territory, systematically exploiting its resources. After the Roman legions withdrew in 271 AD, it was overrun by a succession of various tribes, bringing it under the control of the Carpi, Visigoths, Huns, Gepids, Avars, and Slavs. −

- − Martyn C. Rady: Nobility, Land and Service in Medieval Hungary, Antony Grove Ltd, Great Britain, 2000 −

- Gyula – it is possible that during the 10th century some of the holders of the title of gyula also used Gyula as a personal name, but the issue has been confused because the chronicler of one of the most important primary sources (the Gesta Hungarorum) has been shown to have used titles or even names of places as personal names in some cases.

- "Transylvania". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- Engel, Pal; Andrew Ayton (2005). The Realm of St Stephen. London: Tauris. p. 27. ISBN 1-85043-977-X.

- "Transylvania", Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2008.

- K. Horedt, Contribuţii la istoria Transilvaniei în secolele IV-XIII, Editura Academiei RSR, 1958 p. 113.

- I.M.Țiplic (2000). Considerații cu privire la liniile întarite de tipul prisacilor din transilvania, Acta terrae Septemcastrensis, I, pag. 147-164

- "Settlements and Villages in Transylvania at the Time of the Conquest and in the early Árpádian Period". mek.oszk.hu.

- Madgearu, Alexandru (2001). Românii în opera Notarului Anonim. Cluj-Napoca: Centrul de Studii Transilvane, Fundația Culturală Română. ISBN 973-577-249-3.

- Endre Haraszti; (1977) Origin of the Rumanians (Vlach Origin, Migration and Infiltration to Transylvania) p. 64; Danubian Press, ISBN 0879340177

- "Stephen I". Encyclopedia of World Biography. 14: 427–428. 2004 – via Gale Virtual Reference Library.

- "Hungary". Merriam-Webster's geographical dictionary (3rd ed.). CREDO. 2007.

- Pop, Ioan-Aurel (2006). Romanians in the 14th–16th Centuries: From the "Christian Republic" to the "Restoration of Dacia", In: Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Bolovan, Ioan (2005); History of Romania: Compendium; Romanian Cultural Institute (Center for Transylvanian Studies), p.304, ISBN 978-973-7784-12-4

- Nyárády R. Károly – Erdély népesedéstörténete c. kéziratos munkájábol. Megjelent: A Központi Statisztikai Hivatal Népességtudományi Kutató Intézetenek történeti demográfiai füzetei. 3. sz. Budapest, 1987. 7-55. p., Erdélyi Múzeum. LIX, 1997. 1–2. füz. 1-39. p.

- Sándor Szilágyi: Erdély és az északkeleti háború. Levelek és okiratok Bp. 1890 I. 246–247, 255–256 – Sándor Szilágyi: Transylvania and the northeastern war. Letters and documents Bp. 1890 p. 246–247, 255–256

- "International Boundary Study – No. 47 – April 15, 1965 – Hungary – Romania (Rumania) Boundary" (PDF). US Bureau of Intelligence and Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2009.

- "Diploma Leopoldinum (Transylvanian history)". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2012-07-30.

- "Transylvania (region, Romania)". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2012-07-30.

- Peter F. Sugar. Southeastern Europe Under Ottoman Rule, 1354–1804 (History of East-Central Europe), University of Washington Press, July 1983, page 163, https://books.google.com/books?id=LOln4TGdDHYC&pg=PA163&dq=independent+principality+that+was+not+reunited+with+Hungary&lr=

- John F. Cadzow, Andrew Ludanyi, Louis J. Elteto, Transylvania: The Roots of Ethnic Conflict, Kent State University Press, 1983, page 79, https://books.google.com/books?id=fX5pAAAAMAAJ&q=diploma+leopoldinum+transylvania&dq=diploma+leopoldinum+transylvania&lr=&pgis=1

- Paul Lendvai, Ann Major. "The Hungarians: A Thousand Years of Victory in Defeat" C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2003, page 146; https://books.google.com/books?id=9yCmAQGTW28C&pg=PA146&dq=diploma+leopoldinum+transylvania&lr=

- "Definition of Grand Principality of Transylvania in the Free Online Encyclopedia". Encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved 2012-07-30.

- The Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy and Romanian Political Autonomy Archived 2007-04-24 at the Wayback Machine in Paşcu, Ştefan. A History of Transylvania. Dorset Press, New York, 1990.

- CIA World Factbook, Romania – Government

- Történelmi világatlasz [World Atlas of History] (in Hungarian). Cartographia. 1998. ISBN 963-352-519-5.

- Varga, E. Árpád, Hungarians in Transylvania between 1870 and 1995, Translation by Tamás Sályi, Budapest, March 1999, pp. 30-34

- Keith Hitchins (1994). Romania. Clarendon Press. pp. 486–. ISBN 978-0-19-822126-5.

- Transilvania at romaniatraveltourism.com

- Transylvania at 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- "Microsoft Word – REZULTATE DEFINITIVE RPL2011.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- "Population at 20 October 2011" (in Romanian). INSSE. July 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- "Population on 1 January by age groups and sex – functional urban areas". Eurostat. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- "Sibiu Cultural Capital Website". Archived from the original on 2006-10-15.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-02-02. Retrieved 2017-07-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Elek Fényes, Magyarország statistikája, Vol. 1, Trattner-Károlyi, Pest. VII, 1842

- Seton-Watson, Robert William (1933). "The Problem of Treaty Revision and the Hungarian Frontiers". International Affairs. 12 (4): 481–503. doi:10.2307/2603603. JSTOR 2603603.

- "Transylvania". Columbia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2008-09-05. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-01-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Mark Axworthy, London: Arms and Armour, 1995, Third Axis, Fourth Ally: Romanian Armed Forces in the European War, 1941–1945, pp. 29-30, 75, 149, 222-227 and 239-272

- "Cultura". 2007-12-31. Archived from the original on December 31, 2007. Retrieved 2016-05-08.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Earl A. Pope, "Protestantism in Romania", in Sabrina Petra Ramet (ed.), Protestantism and Politics in Eastern Europe and Russia: The Communist and Postcommunist Eras, Duke University Press, Durham, 1992, p.158-160. ISBN 0-8223-1241-7

- "Situatia demografica a cultelor dupa 1918" (PDF).

- Anuarul statistic al Romaniei, 1937 si 1938

- "Populația stabilă după religie – județe, municipii, orașe, comune". Institutul Național de Statistică.

- "Travel to Romania – Densuș Church (Hunedoara)". Romanianmonasteries.org. 2006-05-31. Retrieved 2012-07-30.

- "Apuseni Caves". Itsromania.com. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2012-07-30.

- "Zilele Filmului de Umor 2014". timisoreni.ro. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "O nouă ediție a Zilelor Filmului de Umor la Timișoara". HotNewsRo. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Dan Cernovodeanu, Știința și arta heraldică în România, Bucharest, 1977, p. 130

- "Coat of arms of Dacia (medieval)". Archived from the original on 9 April 2014.

- Ströhl, Hugo Gerard (1890). Oesterreichish-Ungarische Wappenrolle (PDF). Vienna: Verlag vom Anton Schroll & C°. p. XV. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

Sources

Further reading

- Patrick Leigh Fermor, Between the Woods and the Water (New York Review of Books Classics, 2005; ISBN 1-59017-166-7). Fermor travelled across Transylvania in the summer of 1934, and wrote about it in this account first published more than 50 years later, in 1986.

- Zoltán Farkas and Judit Sós, Transylvania Guidebook

- András Bereznay, Erdély történetének atlasza (Historical Atlas of Transylvania), with text and 102 map plates, the first ever historical atlas of Transylvania (Méry Ratio, 2011; ISBN 978-80-89286-45-4)

- Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Nägler, Thomas; Magyari, András (2018). The History of Transylvania, vol. I-III. Cluj-Napoca: Romanian Academy, Center for Transylvanian Studies – Romanian Cultural Institute. ISBN 978-606-8694-78-8.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Transylvania. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Transylvania. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Transylvania. |

- Radio Transsylvania International

- "Tolerant Transylvania – Why Transylvania will not become another Kosovo", Katherine Lovatt, in Central Europe Review, Vol. 1, No. 14, 27 September 1999.

- The History of Transylvania and the Transylvanian Saxons by Dr. Konrad Gündisch, Oldenburg, Germany

- Transylvania,Its Products and its People, by Charles Boner, 1865

- Transylvanian Family History Database (in Hungarian)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%2C_Cluj%2C_RO.jpg)