Ficus ingens

Ficus ingens, the red-leaved fig, is a fig species with an extensive range in the subtropical to dry tropical regions[2] of Africa and southern Arabia.[3] Despite its specific name, which means "huge", or "vast", it is usually a shrub or tree of modest proportions.[4] It is a fig of variable habit depending on the local climate and substrate, typically a stunted subshrub on elevated rocky ridges, or potentially a large tree on warmer plains and lowlands. In 1829 the missionary Robert Moffat found a rare giant specimen, into which seventeen thatch huts of a native tribe were placed, so as to be out of reach of lions.[5][note 1][note 2]

| Red-leaved fig | |

|---|---|

| |

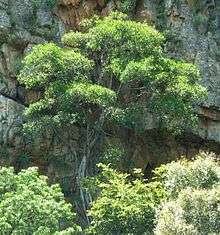

| A specimen exhibiting a rock-splitting habit, and a flush of red new leaves | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | F. ingens |

| Binomial name | |

| Ficus ingens (Miq.) Miq. 1867 | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Distribution and habitat

It is extant in the Saharo-montane woodlands of the Tassili n'Ajjer, the Hoggar, Aïr and Tibesti mountains, and the Kerkour Nourene massif.[2] It is widespread in northern and eastern sub-Saharan Africa,[6] with a more or less contiguous range from Senegal in the west, eastwards to Eritrea, and southwards to the Eastern Cape, South Africa. It is found on rock faces and outcrops, rocky slopes, riparian and wadi fringes, and in dense woodlands.[4] Substrates include lava flows, coral and limestone in drier, exposed areas,[2] and sandstone or dolomite in bushveld.[7]

Description

The smooth and leathery, dull-green leaves are narrowly ovate oblong, bright red brown when young,[8] with conspicuous yellow veins that are prominent beneath[9] and loop along the leaf margin.[5] A leaf measures some 16.5 by 8.5 cm,[5] with the base mostly square[4] or cordate,[8] sometimes broadly rounded, and the apex tapering to a blunt point.[10] Old leaves turn to a reddish-copper colour in autumn.[9]

The almost spherical figs are produced year-round but mainly in summer.[5] They are 0.9 to 1.2 cm[11] in diameter and carried on very short stalks, just below or among the terminal cluster of leaves.[10] They ripen first to a white and eventually a purple[8] or yellowish-brown colour.[9]

The smooth bark is pale grey, while younger branches have a yellow tinge.[10] Bruised or cut stems and leaves exude a non-toxic, milky latex.[9]

Habit and variation

It is deciduous or semi-deciduous and may form a subshrub or shrub, or may form a rounded crown, upwards of 5 meters tall, in sheltered conditions.[9] In the warm lowveld they may form a spreading canopy up to 15 meters tall, with a bole 2 meters in diameter.[10] In the Magaliesberg and Witwatersrand bankenveld they typically straddle boulders or are closely pressed to sunny, north to west-facing (in southern hemisphere) rock faces. Plants of the Eastern Cape are more tomentose.[9]

Uses and species interactions

In northern Nigeria the figs, and in Kenya the leaves and figs, have been recorded as famine food.[12] In South Africa a decoction of the bark mixed with cow feed is said to increase the flow of milk,[13] though the leaves have been shown to be toxic to cattle, and sometimes to sheep.[11] When ripe, the figs are readily eaten by several species of bird.[10] The pollinator wasp is Platyscapa soraria Wiebes., while Otitesella longicauda and O. rotunda are non-pollinators.[3]

Similar species

It is similar to the Wonderboom fig, which has a broadly overlapping range and occurs in comparable habitat. They differ with respect to leaf shape, venation and colour, besides the size and colour of the figs. The Wonderboom is always a tree,[4] and has elliptic-oblong leaves with a rounded bases, that are never bright red-brown.[8] Its figs are much smaller and mature to yellow-red. The Natal fig has the base of the leaf narrowly tapered.[4]

Gallery

Subshrub on sunny slope

Foliage

Figs

Fig placement

Notes

.png)

- Moffat relates it thus: "My attention was arrested by a beautiful and gigantic tree [a species of ficus], standing in a defile ... Seeing some individuals employed under its shade ... and houses in miniature protruding through its evergreen foliage, I proceeded thither, and found that the tree was inhabited by several families of Bakones, ... I ascended by the notched trunk, and found, to my amazement, no less than seventeen of these aerial abodes, and three others unfinished. On reaching the topmost [30 feet up], I entered, and sat down. I asked a woman who sat at the door permission to eat [a bowl full of locusts]. This she granted with pleasure, ... and soon brought me more ... Several more females came from the neighbouring roosts, stepping from branch to branch, to see the stranger, ... I then visited the different abodes, which were on several principal branches. ... A person can nearly stand upright in it: the diameter of the floor is about six feet [with] a little square space before the door." See: Moffat, Robert (1842). Missionary Labours and Scenes in Southern Africa. J. Snow. pp. 519–520: The inhabited tree.

- In the 1960s the tree was rediscovered by Eve Palmer at Boshoek north of Rustenburg. By the 1970s though, it had begun to collapse under its own weight. cf. Swart, W. J. (1984). Die Wildevy: boom van die jaar 1984. Pretoria: Government Printer, Direktoraat van Boswese van die Departement van Omgewingsake, Pamflet 317. ISBN 0621083674.

References

- "The Plant List".

- "Ficus ingens (Miq.) Miq". African Plant Database. Conservatoire et Jardin botaniques & South African National Biodiversity Institute. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- van Noort, S., Rasplus, J. "Ficus ingens (Miquel) Miquel 1867". Figweb. isiko museums. Archived from the original on 5 November 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- Palgrave, K. C. (1984). Trees of Southern Africa. Cape Town: Struik. p. 110. ISBN 0-86977-081-0.

- Jordaan, Marie. "Ficus ingens (Miq.) Miq". PlantZAfrica.com. SANBI. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- "Records: Ficus ingens (Miq.) Miq". Tropicos. Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- De Winter, B. & M.; Killick, D. J. B. (1966). Sixty-Six Transvaal Trees. National Tree List for South Africa. pp. 24–25.

- Palmer, Eve (1977). A Field Guide to the Trees of Southern Africa. London, Johannesburg: Collins. pp. 90–91. ISBN 0-620-05468-9.

- Trees and Shrubs of the Witwatersrand. Johannesburg: Tree Society of South Africa, Witwatersrand University Press. 1974. pp. 24–25. ISBN 0-85494-236-X.

- Mogg, A. O. D. (1975). Important plants of Sterkfontein. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand. pp. 78–79. ISBN 0-85494-426-5.

- Myburgh, J. G.; et al. (1994). "A nervous disorder in cattle cause by the plants Ficus ingens var. ingens and Ficus cordata subsp. salicifolia" (PDF). Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research (61): 171–176. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- Freedman, Robert. "Famine Foods: Moraceae". Purdue Agriculture. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- Lansky, E. P., Paavilainen, H. M. (2010). Figs: The Genus Ficus, Traditional Herbal Medicines for Modern Times. Hoboken: CRC Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-1420089677.

External links