Common chiffchaff

The common chiffchaff (Phylloscopus collybita), or simply the chiffchaff, is a common and widespread leaf warbler which breeds in open woodlands throughout northern and temperate Europe and the Palearctic.

| Common chiffchaff | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Phylloscopidae |

| Genus: | Phylloscopus |

| Species: | P. collybita |

| Binomial name | |

| Phylloscopus collybita (Vieillot, 1817) | |

| |

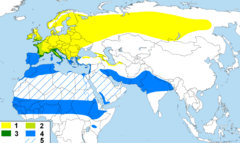

| 1. Breeding; summer only 2. Breeding; small numbers also wintering 3. Breeding; also common in winter 4. Non-breeding winter visitor 5. Localised non-breeding winter visitor in suitable habitat only (oases, irrigated crops) | |

It is a migratory passerine which winters in southern and western Europe, southern Asia and north Africa. Greenish-brown above and off-white below, it is named onomatopoeically for its simple chiff-chaff song. It has a number of subspecies, some of which are now treated as full species. The female builds a domed nest on or near the ground, and assumes most of the responsibility for brooding and feeding the chicks, whilst the male has little involvement in nesting, but defends his territory against rivals, and attacks potential predators.

A small insectivorous bird, it is subject to predation by mammals, such as cats and mustelids, and birds, particularly hawks of the genus Accipiter. Its large range and population mean that its status is secure, although one subspecies is probably extinct.

Taxonomy

The British naturalist Gilbert White was one of the first people to separate the similar-looking common chiffchaff, willow warbler and wood warbler by their songs, as detailed in 1789 in The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne,[2] but the common chiffchaff was first formally described as Sylvia collybita by French ornithologist Louis Vieillot in 1817 in his Nouveau Dictionnaire d'Histoire Naturelle.[3]

Described by German zoologist Friedrich Boie in 1826, the genus Phylloscopus contains about 50 species of small insectivorous Old World woodland warblers which are either greenish or brown above and yellowish, white or buff below. The genus was formerly part of the Old World warbler family Sylvidae, but has now been split off as a separate family Phylloscopidae.[4] The chiffchaff's closest relatives, other than former subspecies, are a group of leaf warblers which similarly lack crown stripes, a yellow rump or obvious wing bars; they include the willow, Bonelli's, wood and plain leaf warblers.[5]

An old synonym, used for the chiffchaff was Phylloscopus rufus (Bechstein).[6]

The common chiffchaff has three still commonly accepted subspecies, together with some from the Iberian Peninsula, the Canary Islands, and the Caucasus which are now more often treated as full species.[7][8]

Subspecies

- P. c. collybita, the nominate form, breeds in Europe east to Poland and Bulgaria, and is described below. It mainly winters in the south of its breeding range around the Mediterranean and in North Africa.[5] It has been expanding its range northwards into Scandinavia since 1970 and close to the southern edge of the range of P. c. abietinus.[9]

- P. c. abietinus occurs in Scandinavia and northern Russia, and winters from southeastern Europe and northeastern Africa east to Iraq and western Iran. It is intermediate in appearance between P. c. tristis and P. c. collybita, being grey-washed olive-green above with a pale yellow supercilium, and underparts whiter than in P. c. collybita,[10] but it has very similar vocalisations to the nominate subspecies.[5] Due to individual variation, it can be difficult to reliably separate P. c. abietinus and P. c. collybita outside their main breeding and wintering ranges.[10] Some common chiffchaffs in the Middle East are browner and have a more disyllabic swee-hu call than P. c. abietinus, and may belong to a poorly known taxon "brevirostris";[11] further research is needed to clarify the affinities of this form.[12]

- P. (c.) tristis, the Siberian chiffchaff, breeds in Siberia east of the Pechora River and winters in the lower Himalayas.[5] It is also regularly recorded in western Europe in winter, and it is likely that the numbers involved have been underestimated due to uncertainties over identification criteria, lack of good data and recording policies (Sweden and Finland only accept trapped birds).[13] It is a dull subspecies, grey or brownish above and whitish below, with little yellow in the plumage, and the buff-white supercilium is often longer than in the western subspecies. It has a higher pitched suitsistsuisit song and a short high-pitched cheet call.[10] It is sometimes considered to be a full species due to its distinctive plumage and vocalisations, being similar to P. s. sindianus in these respects.[14][15] Nominate P. c. collybita and P. c. tristis do not recognize each other's songs.[16][17] Pending resolution of the status of P. (c.) fulvescens, which is found where the ranges of P. c. abietinus and P. c. tristis connect and may[18] or may not[17] be a hybrid between these, tristis is maintained in P. collybita.[8]

Former subspecies

- P. ibericus, the Iberian chiffchaff is brighter, greener on the rump, and yellower below than P. collybita,[5] and has a tit-tit-tit-tswee-tswee song. It was initially named P. brehmii, but the type specimen of that taxon is not an Iberian chiffchaff.[19] This species is found in Portugal and Spain, west of a line stretching roughly from the western Pyrenees[20] via the mountains of central Spain to the Mediterranean; the Iberian and common chiffchaffs co-occur in a narrow band along this line.[21] Apart from the northernmost section, the precise course of the contact zone is not well documented. A long-distance migrant, this species winters in western Africa. It differs from P. c. collybita in vocalisations,[15][20][22] external morphology,[23] and mtDNA sequences.[15][24] There is hybridization in the contact zone,[20][22][25] almost always between male P. ibericus and female P. c. collybita,[25] and hybrids apparently show much decreased fitness;[24] hybrid females appear to be sterile according to Haldane's Rule.[26] Regarding the latter aspect, the Iberian chiffchaff apparently is the oldest lineage of chiffchaffs and quite distinct from the common chiffchaff.[15]

- P. canariensis, the Canary Islands chiffchaff is a non-migratory species formerly occurring on the major Canary Islands, which is differentiated from P. collybita by morphology, vocalisations and genetic characteristics, and, of course, is not sympatric with any other chiffchaffs. The nominate western subspecies P. c. canariensis of El Hierro, La Palma, La Gomera, Tenerife, and Gran Canaria is smaller than common chiffchaff, and has shorter, rounder wings.[15] It is olive-brown above and has a buff breast and flanks;[5] it has a rich deep chip-cheep-cheep-chip-chip-cheep song, and a call similar to the nominate race.[10] The eastern P. c. exsul of Lanzarote and possibly Fuerteventura is paler above and less rufous below than its western relative,[5] and had a harsher call;[10] it might have been a distinct species,[8] but it became extinct in 1986 at latest, probably much earlier. The reasons for its extinction are unclear, but it appears always to have been scarce and localised, occurring only in the Haria Valley of Lanzarote.[27]

- P. sindianus, the mountain chiffchaff, is found in the Caucasus (P. s. lorenzii) and Himalayas (P. s. sindianus), and is an altitudinal migrant, moving to lower levels in winter. The nominate subspecies is similar to P. c. tristis, but with a finer darker bill, browner upperparts and buff flanks; its song is almost identical to P. collybita, but the call is a weak psew. P. s. lorenzii is warmer and darker brown than the nominate race;[5] it is sympatric with common chiffchaff in a small area in the Western Caucasus, but interbreeding occurs rarely, if ever.[14] The mountain chiffchaff differs from tristis in vocalisations,[14][28] external morphology,[29] and mtDNA sequences.[15] Its two subspecies appear to be distinct vocally,[14] and also show some difference in mtDNA sequences;[15] they are maintained at subspecies rank pending further research.[8]

Etymology

The common chiffchaff's English name is onomatopoeic, referring to the repetitive chiff-chaff song of the European subspecies.[30] There are similar names in some other European languages, such as the Dutch tjiftjaf, the German Zilpzalp, Welsh siff-saff and Finnish tiltaltti.[31] The binomial name is of Greek origin; Phylloscopus comes from phyllon/φυλλον, "leaf", and skopeo/σκοπεω, "to look at" or "to see",[32] since this genus comprises species that spend much of their time feeding in trees, while collybita is a corruption of kollubistes, "money changer", the song being likened to the jingling of coins.[30]

Description

The common chiffchaff is a small, dumpy, 10–12 centimetres (4 in) long leaf warbler. The male weighs 7–8 grammes (0.28–0.31 oz), and the female 6–7 grammes (0.25–0.28 oz). The spring adult of the western nominate subspecies P. c. collybita has brown-washed dull green upperparts, off-white underparts becoming yellowish on the flanks, and a short whitish supercilium. It has dark legs, a fine dark bill, and short primary projection (extension of the flight feathers beyond the folded wing). As the plumage wears, it gets duller and browner, and the yellow on the flanks tends to be lost, but after the breeding season there is a prolonged complete moult before migration.[10] The newly fledged juvenile is browner above than the adult, with yellow-white underparts, but moults about 10 weeks after acquiring its first plumage. After moulting, both the adult and the juvenile have brighter and greener upperparts and a paler supercilium.[10]

P. c. collybita

This warbler gets its name from its simple distinctive song, a repetitive cheerful chiff-chaff. This song is one of the first avian signs that spring has returned. Its call is a hweet, less disyllabic than the hooeet of the willow warbler or hu-it of the western Bonelli's warbler.[33]

The song differs from that of the Iberian chiffchaff, which has a shorter djup djup djup wheep wheep chittichittichiittichitta. However, mixed singers occur in the hybridisation zone and elsewhere, and can be difficult to allocate to species.[25]

When not singing, the common chiffchaff can be difficult to distinguish from other leaf warblers with greenish upperparts and whitish underparts, particularly the willow warbler. However, that species has a longer primary projection, a sleeker, brighter appearance and generally pale legs. Bonelli's warbler (P. bonelli) might be confused with the common chiffchaff subspecies tristis, but it has a plain face and green in the wings.[10] The common chiffchaff also has rounded wings in flight, and a diagnostic tail movement consisting of a dip, then sidewards wag, that distinguishes it from other Phylloscopus warblers[34] and gives rise to the name "tailwagger" in India.[27]

Perhaps the greatest challenge is distinguishing non-singing birds of the nominate subspecies from Iberian chiffchaff in the field. In Great Britain and the Netherlands, all accepted records of vagrant Iberian chiffchaffs relate to singing males.[25]

Distribution and habitat

The common chiffchaff breeds across Europe and Asia east to eastern Siberia and north to about 70°N, with isolated populations in northwest Africa, northern and western Turkey and northwestern Iran.[10] It is migratory, but it is one of the first passerine birds to return to its breeding areas in the spring and among the last to leave in late autumn.[33][34] When breeding, it is a bird of open woodlands with some taller trees and ground cover for nesting purposes. These trees are typically at least 5 metres (16 ft) high, with undergrowth that is an open, poor to medium mix of grasses, bracken, nettles or similar plants. Its breeding habitat is quite specific, and even near relatives do not share it; for example, the willow warbler (P. trochilus) prefers younger trees, while the wood warbler (P. sibilatrix) prefers less undergrowth.[10] In winter, the common chiffchaff uses a wider range of habitats including scrub, and is not so dependent on trees. It is often found near water, unlike the willow warbler which tolerates drier habitats. There is an increasing tendency to winter in western Europe well north of the traditional areas, especially in coastal southern England and the mild urban microclimate of London.[10] These overwintering common chiffchaffs include some visitors of the eastern subspecies abietinus and tristis, so they are certainly not all birds which have bred locally, although some undoubtedly are.[34]

Behaviour

Territory

The male common chiffchaff is highly territorial during the breeding season, with a core territory typically 20 metres (66 ft) across, which is fiercely defended against other males. Other small birds may also be attacked. The male is inquisitive and fearless, attacking even dangerous predators like the stoat if they approach the nest, as well as egg-thieves like the Eurasian jay.[10] His song, given from a favoured prominent vantage point, appears to be used to advertise an established territory and contact the female, rather than as a paternity guard strategy.[35]

Beyond the core territory, there is a larger feeding range which is variable in size, but typically ten or more times the area of the breeding territory. It is believed that the female has a larger feeding range than the male.[10] After breeding has finished, this species abandons its territory, and may join small flocks including other warblers prior to migration.[34]

Breeding

The male common chiffchaff returns to its breeding territory two or three weeks before the female and immediately starts singing to establish ownership and attract a female. When a female is located, the male will use a slow butterfly-like flight as part of the courtship ritual, but once a pair-bond has been established, other females will be driven from the territory. The male has little involvement in the nesting process other than defending the territory.[10] The female's nest is built on or near the ground in a concealed site in brambles, nettles or other dense low vegetation. The domed nest has a side entrance, and is constructed from coarse plant material such as dead leaves and grass, with finer material used on the interior before the addition of a lining of feathers. The typical nest is 12.5 centimetres (5 in) high and 11 centimetres (4 in) across.[10]

The clutch is two to seven (normally five or six) cream-coloured eggs which have tiny ruddy, purple or blackish spots and are about 1.5 centimetres (0.6 in) long and 1.2 centimetres (0.5 in) across. They are incubated by the female for 13–14 days before hatching as naked, blind altricial chicks.[10] The female broods and feeds the chicks for another 14–15 days until they fledge. The male rarely participates in feeding, although this sometimes occurs, especially when bad weather limits insect supplies or if the female disappears. After fledging, the young stay in the vicinity of the nest for three to four weeks, and are fed by and roost with the female, although these interactions reduce after approximately the first 14 days. In the north of the range there is only time to raise one brood, due to the short summer, but a second brood is common in central and southern areas.[10]

Although pairs stay together during the breeding season and polygamy is uncommon, even if the male and female return to the same site in the following year there is no apparent recognition or fidelity. Interbreeding with other species, other than those formerly considered as subspecies of P. collybita, is rare, but a few examples are known of hybridisation with the willow warbler. Such hybrids give mixed songs, but the latter alone is not proof of interspecific breeding.[10]

Feeding

Like most Old World warblers, this small species is insectivorous, moving restlessly though foliage or briefly hovering. It has been recorded as taking insects, mainly flies, from more than 50 families, along with other small and medium-sized invertebrates. It will take the eggs and larvae of butterflies and moths, particularly those of the winter moth.[10] The chiffchaff has been estimated to require about one-third of its weight in insects daily, and it feeds almost continuously in the autumn to put on extra fat as fuel for the long migration flight.[10]

Predators and threats

As with most small birds, mortality in the first year of life is high, but adults aged three to four years are regularly recorded, and the record is more than seven years. Eggs, chicks and fledglings of this ground-nesting species are taken by stoats, weasels and crows such as the European magpie, and the adults are hunted by birds of prey, particularly the sparrowhawk. Small birds are also at the mercy of the weather, particularly when migrating, but also on the breeding and wintering grounds.[10]

The common chiffchaff is occasionally a host of brood parasitic cuckoos, including the common and Horsfield's cuckoos,[36] but it recognises and rejects non-mimetic eggs and is therefore only rarely successfully brood-parasitised.[37] Like other passerine birds, the common chiffchaff can also acquire intestinal nematode parasites and external ticks.[38][39]

The main effect of humans on this species is indirect, through woodland clearance which affects the habitat, predation by cats, and collisions with windows, buildings and cars. Only the first of these has the potential to seriously affect populations, but given the huge geographical spread of P. c. abietinus and P. c. tristis, and woodland conservation policies in the range of P. c. collybita, the chiffchaff's future seems assured.[10]

Status

The common chiffchaff has an enormous range, with an estimated global extent of 10 million square kilometres (3.8 million square miles) and a population of 60–120 million individuals in Europe alone. Although global population trends have not been quantified, the species is not believed to approach the thresholds for the population decline criterion of the IUCN Red List (that is, declining more than 30 percent in ten years or three generations). For these reasons, the species is evaluated as "least concern".[1]

None of the major subspecies is under threat, but exsul, as noted above, is probably extinct. There is a slow population increase of common chiffchaff in the Czech Republic.[40] The range of at least P. c. collybita seems to be expanding, with northward advances in Scotland, Norway and Sweden and a large population increase in Denmark.[34]

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Phylloscopus collybita". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- White, Gilbert (1887) [1789]. The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne. London: Cassell & Company. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0-905418-96-4. OCLC 3423785.

- (in French) Vieillot, Louis Jean Pierre (1817): Nouveau Dictionnaire d'Histoire Naturelle nouvelle édition, 11, 235.

- Alström, Per; Ericson, Per G.P.; Olsson, Urban; Sundberg, Per (2006). "Phylogeny and classification of the avian superfamily Sylvioidea". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 38 (2): 381–397. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.05.015. PMID 16054402.

- Baker, Kevin (1997). Warblers of Europe, Asia and North Africa (Helm Identification Guides). London: Helm. pp. 256–259. ISBN 978-0-7136-3971-1.

- For instance in: Rothschild, Walter (1905). "Birds". In Page, William Henry (ed.). The Victoria History of the County of Buckinghamshire. 1. p. 132.

- Clement, P.; Helbig, Andreas J. (1998). "Taxonomy and identification of chiffchaffs in the Western Palearctic". Br. Birds. 91: 361–376.

- Sangster, George; Knox, Alan G.; Helbig, Andreas J.; Parkin, David T. (2002). "Taxonomic recommendations for European birds". Ibis. 144 (1): 153–159. doi:10.1046/j.0019-1019.2001.00026.x.

- Hansson, MC; Bensch, S; Brännström, O (2000). "Range expansion and the possibility of an emerging contact zone between two subspecies of Chiffchaff Phylloscopus collybita ssp". Journal of Avian Biology. 31 (4): 548–558. doi:10.1034/j.1600-048X.2000.1310414.x.

- Clement, Peter (1995). The Chiffchaff. London: Hamlyn. ISBN 978-0-600-57978-6.

- Dubois, Phillipe; Duquet, M. (2008). "Further thoughts on Siberian Chiffchaffs". British Birds. 101: 149–150.

- Dubois, Phillipe (2010). "Presumed 'brevirostris'-type Common Chiffchaffs wintering in Jordan". British Birds. 103: 406–407.

- Dean, Alan; Bradshaw, Colin; Martin, John; Stoddart, Andy; Walbridge, Grahame (2010). "The status in Britain of 'Siberian Chiffchaff'". British Birds. 103: 320–337.

- (in German) Martens, Jochen (1982): Ringförmige Arealüberschneidung und Artbildung beim Zilpzalp, Phylloscopus collybita. Das lorenzii-Problem. Zeitschrift für Zoologische Systematik und Evolutionsforschung 20: 82–100.

- Helbig, Andreas J.; Martens, Jochen; Seibold, I.; Henning, F.; Schottler, B; Wink, Michael (1996). "Phylogeny and species limits in the Palearctic Chiffchaff Phylloscopus collybita complex: mitochondrial genetic differentiation and bioacoustic evidence" (PDF). Ibis. 138 (4): 650–666. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1996.tb04767.x.

- Schubert, M (1982). "Zur Lautgebung mehrerer zentralasiatischer Laubsänger-Arten (Phylloscopus; Aves, Sylviidae)". Mitteilungen aus dem Zoologischen Museum Berlin (in German). 58: 109–128.

- Martens, Jochen; Meincke, C (1989). "Der sibirische Zilpzalp (Phylloscopus collybita tristis): Gesang und Reaktion einer mitteleuropäischen Population im Freilandversuch". Journal für Ornithologie (in German). 130 (4): 455–473. doi:10.1007/BF01918465.

- Marova, I. M.; Leonovich, V. V. (1993). "[Hybridization between Siberian (Phylloscopus collybita tristis) and East European (Ph. collybita abietinus) Chiffchaffs in the area of sympatry.]". Sbornik Trudov Zoologicheskogo Muzeya, Moskovskogo Gosudarstvennogo Universiteta (in Russian). 30: 147–163.

- Svensson, Lars (2001). "The correct name of the Iberian Chiffchaff Phylloscopus ibericus Ticehurst 1937, its identification and new evidence of its winter grounds". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 121: 281–296.

- Salomon, Marc (1989). "Song as a possible reproductive isolating mechanism between two parapatric forms. The case of the chiffchaffs Phylloscopus c. collybita and P. c. brehmii in the western Pyrenees". Behaviour. 111 (1–4): 270–290. doi:10.1163/156853989X00709.

- (in Spanish) Balmori, Alfonso; Cuesta, Miguel Ángel; Caballero, José María (2002): Distribución de los mosquiteros ibérico (Phylloscopus brehmii) y europeo (Phylloscopus collybita) en los bosques de ribera de Castilla y León (España). Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine [With English abstract]. Ardeola 49(1): 19–27.

- Salomon, Marc; Hemim, Y. (1992). "Song variation in the Chiffchaffs (Phylloscopus collybita) of the western Pyrenees – the contact zone between collybita and brehmii forms". Ethology. 92 (4): 265–282. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1992.tb00965.x.

- Salomon, Marc; Bried, J.; Helbig, Andreas J.; Riofrio, J. (1997). "Morphometric differentiation between male Common Chiffchaffs, Phylloscopus [c.] collybita Vieillot, 1817, and Iberian Chiffchaffs, P. [c.] brehmii Homeyer, 1871, in a secondary contact zone (Aves: Sylviidae)". Zoologischer Anzeiger. 236: 25–36.

- Helbig, Andreas J.; Salomon, Marc; Bensch, S.; Seibold, I. (2001). "Male-biased gene flow across an avian hybrid zone: evidence from mitochondrial and microsatellite DNA". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 14 (2): 277–287. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2001.00273.x.

- Collinson, J. Martin; Melling, Tim (April 2008). "Identification of vagrant Iberian Chiffchaffs - pointers, pitfalls and problem birds". British Birds. 101 (4): 174–188.

- (in French) Helbig, Andreas J.; Salomon, Marc; Wink, Michael; Bried, Joël (1993): Absence de flux genique mitochondrial entre le Pouillots "veloces" medio-européen et ibérique (Aves: Phylloscopus collybita, P. (c.) brehmii); implications taxonomiques. Résultats tirés de la PCR et du séquencage d'ADN. C. R. Acad. Sci. III 316: 205–210.

- Simms, Eric (1985). British Warblers (New Naturalist Series). Collins. pp. 286, 310. ISBN 978-0-00-219810-3.

- Martens, Jochen; Hänel, Sabine (1981). "Gesangformen und Verwandtschaft der asiatischen Zilpzalpe Phylloscopus collybita abietinus und Ph. c. sindianus". Journal für Ornithologie (in German). 122 (4): 403–427. doi:10.1007/BF01652928.

- Cramp, Stanley. (ed.) (1992): The Birds of the Western Palearctic, Vol. 6. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Cocker, Mark; Mabey, Richard (2005). Birds Britannica. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 378–9. ISBN 978-0-7011-6907-7.

- Tiltaltti in Glosbe.

- Terres, John K. (1980). The Audubon Society encyclopedia of North American birds. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. p. 1001. ISBN 978-0-517-03288-6.

- Mullarney, Killian; Svensson, Lars, Zetterstrom, Dan; Grant, Peter. (1999). Birds of Europe. London. HarperCollins. pp. 304–306 ISBN 0-00-219728-6

- Snow, David; Perrins, Christopher M., eds. (1998). The Birds of the Western Palearctic concise edition (2 volumes). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-854099-1. p1337–1339

- Rodrigues, Marcos (March 1996). "Song activity in the chiffchaff: territorial defence or mate guarding?". Animal Behaviour. 51 (3): 709–716. doi:10.1006/anbe.1996.0074. S2CID 53189826.

- Johnsgard, Paul A. (1997). The Avian Brood Parasites: Deception at the Nest. Oxford University Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-19-511042-5.

- Moksnes, Arne; Roskaft, Eivin (January–March 1992). "Responses of Some Rare Cuckoo Hosts to Mimetic Model Cuckoo Eggs and to Foreign Conspecific Eggs". Ornis Scandinavica. 23 (1): 17–23. doi:10.2307/3676422. JSTOR 3676422.

- "Cork, Susan C, Grant Report - SEPG 1695". The prevalence of nematode parasites in transcontinental songbirds. British Ecological Society. Archived from the original on 2007-11-21. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

- Jaenson, Thomas G.T.; Jensen, Jens-Kjeld (May 2007). "Records of ticks (Acari, Ixodidae) from the Faroe Islands" (PDF). Norwegian Journal of Entomology. 54: 11–15.

- (in Czech) Budníček menší (Phylloscopus collybita). Česká společnost ornitologická (Czech Society for Ornithology), accessed 20 April 2009

External links

- BBC Science and Nature: BBC chiffchaff site

- BBC Science and Nature: Common chiffchaff song (Real Audio streaming)

- Common chiffchaff videos, photos & sounds on the Internet Bird Collection

- RSPB: Chiffchaff, Phylloscopus collybita

- Ageing and sexing (PDF; 3.5 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze