Tagalog people

The Tagalog people (Baybayin: ) are the second largest ethnolingustic group in the Philippines after the Visayan people, numbering at around 30 million. They have a well developed society due to their cultural heartland, Manila, being the capital city of the Philippines. Most of them inhabit and form a majority in the Metro Manila and Calabarzon regions of southern Luzon, as well as being the largest group in the provinces of Bulacan, Bataan, Zambales, Nueva Ecija and Aurora in Central Luzon and in the islands of Marinduque and Mindoro in Mimaropa.

A Maginoo (noble class) couple, both wearing blue-coloured clothing articles (blue being the distinctive colour of their class). | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 30 million (in the Philippines)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

(Metro Manila, Calabarzon, Central Luzon, Mimaropa) | |

| Languages | |

| Tagalog (Filipino) English (auxiliary) Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Christianity Muslim, Buddhist, Anitism (Tagalog religion) minorities | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Filipino ethnic groups |

Etymology

The commonly accepted origin for the endonym "Tagalog" is the term tagá-ilog, which means "people from [along] the river". An alternative theory states that the name is derived from tagá-alog, which means "people from the ford" (the prefix tagá- meaning "coming from" or "native of").[2]

In 1821, American diplomat Edmund Roberts called the Tagalog "Tagalor" in his memoirs about his trips to the Philippines.[3]

History

The Angono Petroglyphs in Rizal were most likely been made by Austronesian peoples, of which the most likely are the ancestors of the Tagalog people. There are 127 human and animal figures engraved on the rock wall, that were probably carved during the late Neolithic, or before 2000 BC. According to archaeologists, the human figures on the wall were infants, and that the ancient Tagalogs most likely believed that drawing the figures of their sick children on the 'sacred wall' would clear their children from diseases.

The earliest written record of Tagalog is a late 9th-century document known as the Laguna Copperplate Inscription which is about a remission of debt on behalf of the ruler of Tondo.[4] Inscribed on it is year 822 of the Saka Era, the month of Waisaka, and the fourth day of the waning moon, which corresponds to Monday, April 21, 900 CE in the Proleptic Gregorian calendar.[5] The writing system used is the Kawi script, while the language is a variety of Old Malay, and contains numerous loanwords from Sanskrit and a few non-Malay vocabulary elements whose origin may be Old Javanese. Some contend it is between Old Tagalog and Old Javanese.[6] The document states that it releases its bearers, the children of Namwaran, from a debt in gold amounting to 1 kati and 8 suwarnas (865 grams).[7][5] Around the creation of the copperplate, a complex society with sarcophagi burial practices developed in the Bondok peninsula in Quezon province. Also, the polities in Namayan, Manila, and Tondo, all in the Pasig river tributary, were established. Various Tagalog societies were also established in Calatagan, Tayabas, shores of Lake Laguna, Marinduque, and Malolos. The enhancements of these Tagalog societies until the middle of the 16th century made it possible for other Tagalog societies to spread and develop various cultural practices such as those concerning the dambana. During the reign of Sultan Bolkiah in 1485 to 1521, the Sultanate of Brunei decided to break Tondo's monopoly in the China trade by attacking Tondo and establishing Selurung as a Bruneian satellite-state.[8][9]

The most known unification of barangays in pre-colonial Tagalog history are the unification of Tondo barangays (those at the northern edge of the Pasig river), the unification of Manila barangays (those at the southern edge of the Pasig river), the unification of Namayan barangays (those upstream of the Pasig), the unification of Kumintang barangays (those west of Batangas), and the unification of Pangil barangays (those east and south of Laguna de Bay). The first two barangay unification were most likely triggered by conflicts between the two Tagalog sides of the river, while the Namayan unification was most likely triggered by economic means as all trade between the barangays around Laguna de Bay and barangays at Manila Bay need to pass through Namayan via the Pasig river. The unification of Kumintang barangays was probably due to economic ties as traders from East Asia flocked the area, while the unification of Pangil barangays was said to be due to a certain Gat Pangilwhil unified the barangays under his lakanship. Present-day Tondo is the southern section of Manila's Tondo district, while present-day Maynila is Manila's Intramuros district. Present-day Namayan is Manila's Santa Ana district. Present-day Pangil is the eastern and southern shores of Laguna and a small portion of northern Quezon province. Present-day Kumintang is the areas of western Batangas. The Kumintang barangays are sometimes referred as the 'homeland' of the Tagalog people, however, it is contested by the Tagalogs of Manila.[10]

Tomé Pires noted that the Luções or people from Luzon were "mostly heathen" and were not much esteemed in Malacca at the time he was there, although he also noted that they were strong, industrious, given to useful pursuits. Pires' exploration led him to discover that in their own country, the Luções had foodstuffs, wax, honey, inferior grade gold, had no king, and were governed instead by a group of elders. They traded with tribes from Borneo and Indonesia and Filipino historians note that the language of the Luções was one of the 80 different languages spoken in Malacca.[11] When Magellan's ship arrived in the Philippines, Pigafetta noted that there were Luções there collecting sandalwood.[12] Contact with the rest of Southeast Asia led to the creation of Baybayin script that was later used in the book Doctrina Cristiana, which is written by the 16th century Spanish colonizers.[13]

On May 19, 1571, Miguel López de Legazpi gave the title "city" to the colony of Manila.[14] The title was certified on June 19, 1572.[14] Under Spain, Manila became the colonial entrepot in the Far East. The Philippines was a Spanish colony administered under the Viceroyalty of New Spain and the Governor-General of the Philippines who ruled from Manila was sub-ordinate to the Viceroy in Mexico City.[15] Throughout the 333 years of Spanish rule, various grammars and dictionaries were written by Spanish clergymen, including Vocabulario de la lengua tagala by Pedro de San Buenaventura (Pila, Laguna, 1613), Pablo Clain's Vocabulario de la lengua tagala (beginning of the 18th century), Vocabulario de la lengua tagala (1835), and Arte de la lengua tagala y manual tagalog para la administración de los Santos Sacramentos (1850) in addition to early studies of the language.[16] The first substantial dictionary of Tagalog language was written by the Czech Jesuit missionary Pablo Clain in the beginning of the 18th century.[17] Further compilation of his substantial work was prepared by P. Juan de Noceda and P. Pedro de Sanlucar and published as Vocabulario de la lengua tagala in Manila in 1754 and then repeatedly[18] re-edited, with the last edition being in 2013 in Manila.[19] The indigenous poet Francisco Baltazar (1788–1862) is regarded as the foremost Tagalog writer, his most notable work being the early 19th-century epic Florante at Laura.[20]

Prior to Spanish arrival and Catholic seeding, the ancient Tagalog people used to cover the following: present-day Calabarzon region except the Polillo Islands, northern Quezon, Alabat island, the Bondoc Peninsula, and easternmost Quezon; Marinduque; Bulacan except for its eastern part; and southwest Nueva Ecija, as much of Nueva Ecija used to be a vast rainforest where numerous nomadic ethnic groups stayed and left. When the polities of Tondo and Maynila fell due to the Spanish, the Tagalog-majority areas grew through Tagalog migrations in portions of Central Luzon and north Mimaropa as a Tagalog migration policy was implemented by Spain. This was continued by the Americans when they defeated Spain in a war.

The first Asian-origin people known to arrive in North America after the beginning of European colonization were a group of Filipinos known as "Luzonians" or Luzon Indians who were part of the crew and landing party of the Spanish galleon Nuestra Señora de la Buena Esperanza. The ship set sail from Macau and landed in Morro Bay in what is now the California coast on October 17 of 1587, as part of the Galleon Trade between the Spanish East Indies (the colonial name for what would become the Philippines) and New Spain (Spain's Viceroyalty in North America).[21] More Filipino sailors arrived along the California coast when both places were part of the Spanish Empire.[22] By 1763, "Manila men" or "Tagalas" had established a settlement called St. Malo on the outskirts of New Orleans, Louisiana.[23]

The Tagalog played an active role during the 1896 Philippine Revolution and many of its leaders were either from Manila or surrounding provinces.[24] The Katipunan once intended to name the Philippines as "Katagalugan" or the Tagalog Republic,[25] and extended the meaning of these terms to all natives in the Philippine islands.[26][27] Miguel de Unamuno described revolutionary leader José Rizal (1861–1896) as the "Tagalog Hamlet" and said of him “a soul that dreads the revolution although deep down desires it. He pivots between fear and hope, between faith and despair.”[28] In 1902, Macario Sakay formed his own Republika ng Katagalugan in the mountains of Morong (today, the province of Rizal), and held the presidency with Francisco Carreón as vice president.[29]

Tagalog was declared the official language by the first constitution in the Philippines, the Constitution of Biak-na-Bato in 1897.[30] In 1935, the Philippine constitution designated English and Spanish as official languages, but mandated the development and adoption of a common national language based on one of the existing native languages.[31] After study and deliberation, the National Language Institute, a committee composed of seven members who represented various regions in the Philippines, chose Tagalog as the basis for the evolution and adoption of the national language of the Philippines.[32][33] President Manuel L. Quezon then, on December 30, 1937, proclaimed the selection of the Tagalog language to be used as the basis for the evolution and adoption of the national language of the Philippines.[32] In 1939, President Quezon renamed the proposed Tagalog-based national language as wikang pambansâ (national language).[33] In 1959, the language was further renamed as "Pilipino".[33] The 1973 constitution designated the Tagalog-based "Pilipino", along with English, as an official language and mandated the development and formal adoption of a common national language to be known as Filipino.[34] The 1987 constitution designated Filipino as the national language mandating that as it evolves, it shall be further developed and enriched on the basis of existing Philippine and other languages.[35]

Society

The Tagalog number around 30 million, making them the largest indigenous Filipino ethno-linguistic group in the country. The second largest is the Sebwano with around 20 million.[36] Tagalog settlements are generally lowland, and are commonly sited on the banks near the delta and "wawà" or mouth of a river.[37] The traditional clothing of the Tagalog, the Barong Tagalog, is the folk costume of the Philippines, while the national language of the Philippines, which is Filipino, is derived mainly from the Tagalog language.[38]

The Tagalog mostly practice Christianity (majority Catholicism and minority Protestantism) with a minority practicing Islam, Buddhism, Anitism (indigenous Tagalog religion), and other religions as well as no religion.[37]

Cuisine

Bulacan is popular for chicharon (crunchy pork rind), steamed rice and tuber cakes like puto. It is a center for panghimagas or desserts, like brown rice cake or kutsinta, sapin-sapin, suman, cassava cake, halaya ube and the king of sweets, in San Miguel, Bulacan, the famous carabao milk candy pastillas de leche, with its pabalat wrapper.[39] Antipolo, the capital of Rizal province, straddled mid-level in the mountainous regions of the Philippine Sierra Madre, is a city known for its suman and cashew products. Cainta, also in Rizal, is also known for its suman rice cakes and puddings. These are usually topped with latik, a mixture of coconut milk and brown sugar, reduced to a dry crumbly texture. A more modern and time saving alternative to latik are coconut flakes toasted in a frying pan.

Laguna is known for buko pie (coconut pie) and panutsa (peanut brittle). Batangas is home to Taal Lake, a body of water that surrounds Taal Volcano. The lake is home to 75 species of freshwater fish. Among these, the maliputo and tawilis are two not commonly found elsewhere. These fish are delicious native delicacies. Batangas is also known for its special coffee, the strong-tasting kapeng barako. Bistek Tagalog is a dish of strips of sirloin beef slowly cooked in soy sauce, calamansi juice, vinegar and onions. Records have also shown that kare-kare is the Tagalog dish that the Spanish first tasted when they landed in pre-colonial Tondo.[40]

Clothing

.jpg)

.jpg)

The majority of Tagalogs before colonization wore garments woven by the locals, much of which showed sophisticated designs and techniques. The Boxer Codex also illuminates the intricate and high standard in Tagalog clothing, especially among the gold-draped high society. High society members, which include the datu and the katolonan, also wore accessories made of prized materials. Slaves on the other hand wore simple clothing, seldom loincloths.

During later centuries, Tagalog nobles would wear the barong tagalog for men and the baro't saya for women. When the Philippines became independent, the barong Tagalog became popularised as the national costume of the country, as the wearers were the majority in the new capital, Manila.

Craftsmanship

The Tagalog people were also craftsmen. The katolanan, specifically, of each barangay is tasked as the holder of arts and culture, and usually trains craftfolks if ever no craftfolks are living in the barangay. If the barangay has a craftsfolk, the present crafts-folks would teach their crafts to gifted students. Notable crafts made by ancient Tagalogs are boats, fans, agricultural materials, livestock instruments, spears, arrows, shields, accessories, jewelries, clothing, houses, paddles, fish gears, mortar and pestles, food utensils, musical instruments, bamboo and metal wears for inscribing messages, clay wears, toys, and many others.

Belief on the soul and pangangaluluwa

The Tagalog people traditionally believe in the two forms of the soul. The first is known as the kakambal (literally means twin), which is the soul of the living. Every time a person sleeps, the kakambal may travel to many mundane and supernatural places which sometimes leads to nightmares if a terrible event is encountered while the kakambal is travelling. When a person dies, the kakambal is ultimately transformed into the second form of the Tagalog soul, which is the kaluluwa (literally means spirit). In traditional Tagalog religion, the kaluluwa then travels to either Kasanaan (if the person was evil when he was living) or Maca (if the person was good when he was living) through sacred tomb-equipped psychopomp creatures known as buwaya[41][41] or through divine intervention. Both domains are ruled by Bathala, though Kasanaan is also ruled by the deity of souls.[42]

In addition to the belief in the kaluluwa, a tradition called pangangaluluwa sprang. The pangangaluluwa is a traditional Tagalog way of aiding ancestor spirits to arrive well in Maca (place where good spirits go) or to make ancestor spirits that may have been sent to Kasanaan/Kasamaan (place where bad spirits go) be given a chance to be cleansed and go to Maca. The tradition includes the peoples (which represent the kaluluwa of people who have passed on), and their oral tradition conducted through a recitation or song. The people also ask for alms from townsfolk, where the alms are offered to the kaluluwa afterwards. This tradition, now absorbed even in the Christian beliefs of Tagalogs, is modernly-held between October 27 to November 1, although it may be held on any day of the year if need be during the old days. The traditional pangangaluluwa song's composition is:[43][44] Kaluluwa’y dumaratal (The second souls are arriving); Sa tapat ng durungawan (In front of the window); Kampanilya’y tinatantang (The bells are ringing); Ginigising ang may buhay (Waking up those who still have life); Kung kami po’y lilimusan (If we are to be asked to give alms); Dali-daliin po lamang (Make it faster); Baka kami’y mapagsarhan (We may be shut); Ng Pinto ng Kalangitan (From the doors of heaven).[43] The Kalangitan in the lyrics would have been Maca during the classical era.[43][44]

Additional lyrics are present in some localities. An example is the additional 4 lines from Nueva Ecija:[43][44] Bukas po ng umaga (Tomorrow morning); Tayong lahat ay magsisimba (We will go to the shrine); Doon natin makikita (There, we will see); Ang misa ng kaluluwa! (The mass of the second souls!)[43]

Belief on dreams

The Tagalog people traditionally believe that when a person sleeps, he may or may not dream the omens of Bathala. The omens are either hazy illusions within a dream, the appearance of an omen creature such as tigmamanukan, or sightings from the future. The dream omens do not leave traces on what a person must do to prevent or let the dream come true as it is up to the person to make the proper actions to prevent or make the dream come true. The omen dreams are only warnings and possibilities 'drafted by Bathala'.

Additionally, a person may sometimes encounter nightmares in dreams. There are two reasons why nightmares occur, the first is when the kakambal soul encounters a terrifying event while travelling from the body, or when a bangungot creature sits on top of the sleeping person in a bid of vengeance due to the cutting of her tree home. Majority of the nightmares are said to be due to the kakambal soul encountering terrifying events while travelling.[42][45]

Belief on the cosmos

Ancient Tagalogs initially believed that the first deity of the sun and moon was Bathala, as he is a primordial deity and the deity of everything. Later on, the title of deity of the moon was passed on to his favorite daughter, Mayari, while the title of deity of the sun was passed on to his grandson and honorary son, Apolaki. One of his daughters, Tala is the deity of the stars and is the primary deity of the constellations, while Hanan was the deity of mornings and the new age. The Tagalog cosmic beliefs is not exempted from the moon-swallowing serpent myths prevalent throughout the different ethnic peoples of the Philippines. But unlike the moon-swallowing serpent stories of other ethnic peoples, which usually portrays the serpent as a god, the Tagalog people believe that the serpent which causes eclipses is a monster dragon, called Laho, instead. The dragon, despite being strong, can easily be defeated by Mayari, the reason why the moon's darkness during eclipses diminishes within minutes.[46]

Additionally, the Tagalogs also had their own indigenous names for various constellations. An example is Balatik (Western counterpart is Orion) which is depicted as a hunting trap.[47]

Burial practices

The Tagalog people had numerous burial practices prior to Spanish colonization and Catholic introduction. These practices include, but not limited to, tree burials, cremation burials, sarcophagus burials, and underground burials.[48][49]

In rural areas of Cavite, trees are used as burial places. The dying person chooses the tree beforehand, thus when he or she becomes terminally ill or is evidently going to die because of old age, a hut is built close to the said tree. The deceased's corpse is then entombed vertically inside the hollowed-out tree trunk. Before colonization, a statue known as likha is also entombed with the dead inside the tree trunk. In Pila, Laguna, a complex cremation-burial practice existed, where the body is let alone to decompose first. It is then followed by a ritual performance. The body is burned afterwards through cremation because, according to the belief of ancient people, the “spirit is as clean as though washed in gold" once the body is set on fire. Likha statues were also found in various cremation burial sites.[49] In Mulanay, Quezon and nearby areas, the dead are entombed inside limestone sarcophagi along with a likha statue. However, the practice vanished in the 16th century due to Spanish colonization. In Calatagan, Batangas and nearby areas, the dead are buried under the earth along with likha statues. The statues, measuring 6–12 inches, are personified depictions of anitos. Likha statues are not limited to burial practices as they are also used in homes, prayers, agriculture, medicine, travel, and other means; when these statues are used as such, they are known as larauan, which literally means image.[48]

Additionally, these statues that were buried with the dead are afterwards collected and revered as representatives of the dead loved one. The statues afterwards serve as a connection of mortals to the divine and the afterlife.[50] When the Spanish arrived, they recorded these statues in some accounts. The Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas of 1582 noted that there were even houses that contained "one hundred or two hundred of these idols". In the name colonization, the Spanish destroyed these statues throughout the archipelago. In present-time, only two statues (made of stone) have been found in good condition. These two statues are currently housed in the National Museum of the Philippines in Manila.[50]

Sacred animals, trees, and number

The ancient Tagalogs believed that there are three fauna and three flora that are deemed the most sacred. The three sacred fauna include dogs which are blessed by the deities to guide and become allies with mankind, tigmamanukans which are the messengers of Bathala, crocodiles which are guardians of sacred swamps and believed to be psychopomps,[51] while the three sacred flora include coconut palms which are the first vegetation from the ashes of Galang Kaluluwa and Ulilang Kaluluwa, balete trees which are home to the supernaturals, and bamboos which is where mankind sprang from.[52][10][53] The number three is believed to be sacred in ancient Tagalog beliefs. When Bathala and Ulilang Kaluluwa battled during the cosmic creation, the war lasted for three days and three nights. Additionally, Bathala had three divine daughters (Mayari, Tala, and Hanan) from a mortal women, and there are three divine abodes, namely, Maca, Kasamaan, and Kaluwalhatian. Also, there were three divine beings during the cosmic creation, Bathala, Ulilang Kaluluwa, and Galang Kaluluwa. Later on, when Galang Kaluluwa and Ulilang Kaluluwa died, Aman Sinaya and Amihan joined Bathala in the trinity of deities. In later stories, Aman Sinaya chose to dwell underneath the ocean while Amihan chose to travel throughout the middleworld. During that time, the trinity of deities became Bathala, Lakapati, and Meylupa. Meylupa was later replaced by Sitan after Meylupa chose to live as a hermit. In the most recent trinity, after Bathala died (or went into a deep slumber according to other sources), the trinity consisted of Mayari, Apolaki, and Sitan.[50]

A 2018 archaeological research found that Tagalog dogs were indeed held in high regard prior to colonization and were treated as equals, backing the oral knowledge stating that dogs are beings blessed by the deities. Dogs were buried, never as sacrificial offerings or when a master dies, but always "individually", having their own right to proper burial practices. A burial site in Santa Ana, Manila exhibited a dog which was first buried, and after a few years, the dog's human child companion who died was buried above the dog's burial, exemplifying the human prestige given to dogs in ancient Tagalog beliefs.[54][55]

Religion

The Tagalog people initially had their own unique religion, modernly known as Tagalismo as the original name of the religion is unknown and was not documented by the Spanish. Spanish accounts also call the Tagalog religion as Anitismo (or Anitism in English) and Anitheria, the former is accepted by Tagalog scholars and present-day Anitist adherents while the later is seen as a derogatory term. The practices of Tagalismo were usually done within a dambana. When the Spanish arrived, Roman Catholicism was forcefully inputted by the colonizers who tried to destroy all other religions they deemed as 'lesser' than European religions. At the present, the majority of Tagalogs belong to the Roman Catholic Church, while a relatively smaller amount belong to various Protestant sects or nationalized Christian Churches. A small number of Tagalogs, however, have managed to revert to Tagalismo/Anitismo. Some Tagalogs also adhere to Islam, although their number is extremely small and fragmented.

Anitism/Tagalismo

The pre-colonial religion of the Tagalog people was a Syncretic form of indigenous Tagalog belief systems, Hinduism, and Buddhism. The religion revolved around the community through the Katalonan and the dambana, known also as lambana in the Old Tagalog language.[56][57][58] This shamanistic mix of polytheism and animism was collectively called Tagalismo (Tagalog religion) or Anitism (Anito religion).

Immortals

- Bathala: supreme god and creator deity, also known as Bathala Maykapal, Lumilikha, and Abba; an enormous being with control over thunder, lightning, flood, fire, thunder, and earthquakes; presides over lesser deities and uses spirits to intercede between divinities and mortals[59][60]; referred by Muslims as Anatala[61]; the tigmamanuquin (tigmamanukan) is attributed to Bathala[62]

- Primordial Kite: caused the sky and the sea to war, which resulted in the sky to throw boulders at the sea, creating islands; built a nest on an island and left the sky and sea in peace[63]

- Unnamed God: the god of vices mentioned as a rival of Bathala[64]

- Mayari: goddess of the moon[65]; sometimes identified as having one eye[66]; ruler of the world during nighttime and daughter of Bathala[67]

- Hanan: goddess of the morning[68]; daughter of Bathala[69]

- Tala: goddess of stars[70]; daughter of Bathala[71]; also called Bulak Tala, deity of the morning star, the planet Venus seen at dawn[72]

- Idianale: goddess of labor, good deeds; sometimes referred as a goddess of the rice fields[73][74]; a patron of cultivated lands and husbandry[75]

- Dumangan: god of good harvest married to Idianale[76]

- Dumakulem: guardian of created mountains, son of Idianale and Dumangan, married to Anagolay[77]

- Anitun Tabu: goddess of wind and rain and daughter of Idianale and Dumangan[78]

- Amanikable: god of the sea who was spurned by the first mortal woman; also a god of hunters[79][80]

- Lakapati: hermaphrodite deity and protector of sown fields, sufficient field waters, and abundant fish catch[81]; a major fertility deity[82]; deity of vagrants and waifs[83]; a patron of cultivated lands and husbandry[84]

- Ikapati: goddess of cultivated land and fertility[85]

- Mapulon: god of seasons married to Ikapati[86]

- Anagolay: goddess of lost things and daughter of Ikapati and Mapulon[87]

- Apolake: god of sun and warriors[88]; son of Anagolay and Dumakulem[89]; sometimes referred as son of Bathala and brother of Mayari; ruler of the world during daytime[90]

- Dian Masalanta: goddess of lovers, daughter of Anagolay and Dumakulem[91]; a patron of lovers and of generation; the Spanish called the deity Alpriapo, as compared with the Western deity Priapus[92]

- Lakan-bakod: god of the fruits of the earth who dwells in certain plants[93]; the god of crops[94]; the god of rice whose hollow statues have gilded eyes, teeth, and genitals; food and wine are introduced to his mouth to secure a good crop[95]; the protector of fences[96]

- Sidapa: god of war who settles disputes among mortals[97]

- Amansinaya: goddess of fishermen[98]

- Amihan: a primordial deity who intervened when Bathala and Amansinaya were waging a war[99]; a gentle wind deity, daughter of Bathala, who plays during half of the year, as playing together with her brother, Habagat, will be too much for the world to handle[100]

- Habagat: an active wind deity, son of Bathala, who plays during half of the year, as playing together with his sister, Amihan, will be too much for the world to handle[101]

- Protectors of the Abode of Souls

- Sitan: torturer of souls in the lower world called Kasanaan; has many lower divinities that do his bidding[104]; fought with Bathala for the battle of mortal souls[105]

- Divinities under Sitan

- Mangaguay: spreader of disease and suffering; roams the mortal world to induce maladies with her charms[106][107]

- Manisilat: makes broken homes by turning spouses against each other[108]

- Mangkukulam: pretends to be a doctor and emits fire[109]

- Hukloban: can change into any form she desires[110][111]

- Priestly Agents of the Divinities

- Silagan: tempt people and eat the liver of those who wear white during mourning; sibling of Mananangal[112]

- Mananangal: frightens people as she has no head, hands, and feet; sister of Silagan[113]

- Asuan: flies at night and murder men; one of the five agent brothers[114]

- Mangagayuma: specializing in charms, especially those which infuses the heart with love; one of the five agent brothers[115]

- Sunat: a well-known priest; one of the five agent brothers[116]

- Pangatahuyan: a soothsayer; one of the five agent brothers[117]

- Bayuguin: tempts women into a life of shame; one of the five agent brothers[118]

- Sinukan: tasked her lover Bayani to complete a bridge[119]

- Bayani: lover of Sinukan who failed to complete a bridge; engulfed by a stream caused by the wrath of Sinukan[120]

- Ulilangkalulua: a giant snake that could fly; enemy of Bathala, who was killed during their combat[121][122]

- Galangkalulua: winged god who loves to travel; Bathala's companion who perished due to an illness, where his head was buried in Ulilangkalulua's grave, giving birth to the first coconut tree, which was used by Bathala to create the first humans[123][124]

- Uwinan Sana: the god of the fields and the jungle[125]

- Haik: the god of the sea who protects travelers from tempests and storms[126]

- Lakambini: the deity who protects throats and who is invoked to cure throat aches; also called Lakandaytan, as the god of attachment[127]

- Lakang Balingasay: deity who resides in the poisonous balingasay tree; a feared and powerful spirit of the jungle; compared with the Western divinity Beezlebub, the deity of flies[128]

- Bighari: the flower-loving goddess of the rainbow; a daughter of Bathala[129]

- Bibit: deity who is offered food first when somebody is sick[130]

- Linga: deity invoked by the sick[131]

- Liwayway: the goddess of dawn; a daughter of Bathala[132]

- Tag-ani: the god of harvest; a son of Bathala[133]

- Kidlat: the god of lightning; a son of Bathala[134]

- Hangin: the god of wind; a son of Bathala[135]

- Bulan-hari: one of the deities sent by Bathala to aid the people of Pinak; can command rain to fall; married to Bitu-in[136]

- Bitu-in: one of the deities sent by Bathala to aid the people of Pinak[137]

- Alitaptap: daughter of Bulan-hari and Bitu-in; has a star on her forehead, which was struck by Bulan-hari, resulting to her death; her struck star became the fireflies[138]

- Makiling: the kind goddess of Mount Makiling and protector of its environment and wildlife[139]

- Maylupa: also called Meylupa, the crow master of the earth[140]

- Alagaka: the protector of hunters[141]

- Bingsol: the god of ploughmen[142]

- Biso: the police officer of heaven[143]

- Bulak Pandan: deity of the cotton of pandanus[144]

- Dalagang nasa Buwan: the maiden of the moon[145]

- Ginuong Dalaga: the goddess of crops[146]

- Dalagang Binubukot: the cloistered maiden in the moon[147]

- Ginuong Ganay: the lady old maid[148]

- Hasanggan: a terrible god[149]

- Kampungan: the god of harvests and sown fields[150]

- Kapiso Pabalita: the news-giving protector of travelers[151]

- Lampinsaka: the god of the lame and cripple[152]

- Makapulaw: the god of sailors[153]

- Makatalubhay: the god of bananas[154]

- Matanda: the god of merchants and second-hand dealers[155]

- Ang Maygawa: the owner of the work[156]

- Paalulong: the god of the sick and the dead[157]

- Paglingniyalan: the god of hunters[158]

- Ginuong Pagsuutan: the protectress of women and travail[159]

- Lakang Pinay: the old midwife-lord[160]

- Pusod-Lupa: the earth-navel and a god of the fields[161]

- Sirit: a servant of the gods with a snake's hiss[162]

- Sungmasandal: the one that keeps close[163]

- Pilipit: a divinity whose statuette looks like a cat, where solemn oaths are made in the deity's presence[164]

- Mangkukutod: protector of palm trees[165]

- Bernardo Carpio: a giant trapped between two mountains in Montalban; his movements create earthquakes[166]

- Sawa: a deity who assumed the form of a giant snake when he appeared to a priestess in a cave-temple[167]

- Rajo: a giant who stole the formula for creating wine from the gods; tattled by the night watchman who is the moon; his conflict with the moon became the lunar eclipse[168]

- Unnamed Moon God: the night watchman who tattled on Rajo's theft, leading to an eclipse[169]

- Nuno: the owner of the mountain of Taal, who disallowed human agriculture at Taal's summit[170]

Mortals

Roman Catholicism

Roman Catholicism first arrived in Tagalog areas in the Philippines during the 16th century when the Spanish toppled the polities of Tondo and Maynila in the Pasig River. They later on imposed the European religion, and tried to replace the shamanistic belief systems of the natives. By the 18th century, majority of Tagalogs have adhered to Roman Catholicism, however, the shamanistic beliefs and other indigenous belief systems of Tagalogs were passed down secretly by the natives to the younger generations, effectively preserving their beliefs of creatures and supernatural crafts. In present time, the majority of Tagalogs continue to adhere to Roman Catholicism. The biggest Catholic procession in the Philippines is currently the Pista ng Itim na Nazareno (Feast of the Black Nazarene), which is dominantly Tagalog in nature.

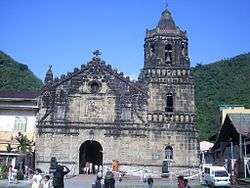

For Tagalog Catholics, sacred sites include cathedrals, basilicas, churches, chapels, and cemeteries. However, due to the belief systems passed down from Tagalismo, certain mountains are also valued as sacred sites, such as Mount Makiling and Mount Banahaw.

Language and writing system

Indigenous

The language of the Tagalog people evolved from Old Tagalog to Modern Tagalog. Modern Tagalog has five distinct dialects:

- The Northern Tagalog (Nueva Ecija, Bulacan, Zambales, and Bataan) has words in-putted into it from the Kapampangan and Ilocano languages.

- Southern Tagalog (Batangas and Quezon) is unique as it necessitate the use of Tagalog without the combination of the English languages.

- In contrast, Central Tagalog (Manila, Cavite, Laguna, and Rizal except Tanay) is predominantly a mixture of Tagalog and English.

- The Tagalog of Tanay maintains usage of the most native words despite influx from other cultures; it is the only highly preserved Tagalog dialect in mainland Luzon and is the most endangered Tagalog dialect.

- Lastly, the Marinduque Tagalog dialect is known as the purest of all Tagalog dialects, as the dialect has little influence from past colonizers.

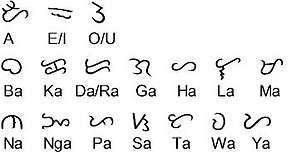

The writing suyat script of the indigenous Tagalogs is the Baybayin. Only few people today know how to read and write in Baybayin. Due to this, the ancient writing script of the Tagalog has been regarded as nearly extinct. A bill in Congress has been filed to make Baybayin the country's national script, however, it is still pending in the Senate and the House of Representatives. Nowadays, the Baybayin is artistically expressed in calligraphy, as it has been traditionally.

The Tagalog people are also known for their tanaga, an indigenous artistic poetic form of the Tagalog people's idioms, feelings, teachings, and ways of life. The tanaga strictly has four lines only, each having seven syllables only.

Colonial

The Tagalog people were skilled Spanish speakers from the 18th to 19th centuries due to the Spanish colonial occupation era. When the Americans arrived, English became the most important language in the 20th century. At present-time, the language of the Tagalogs are Tagalog, English, and a mix of the two, known in Tagalog pop culture as Taglish. Some Spanish words are still used by the Tagalog, though sentence construction in Spanish is no longer used.

The Spanish introduced the Roman alphabet as the writing script of the Philippines in the 16th century after destroying countless documents with Baybayin suyat writings. Eventually, the Roman alphabet replaced Baybayin after the Spanish colonial government imposed sanctions, usually by force, to all natives who continue to use the native Tagalog script.

Heritage towns and cities

The predominantly Tagalog provinces of the Philippines possess the most heritage towns and cities in the entire country, notably due to their proximity with the capital, Manila, which is also dominated by the Tagalog people. Numerous heritage structures in the following towns and cities attract tourists annually, the most famous of which are Manila, Taal, and Malolos. At present, the Tagalog people's regions are home to the UNESCO World Heritage Site of San Agustin Church in Manila and the ASEAN Heritage Park of Mount Makiling in Laguna.

City of Gapan, Nueva Ecija

City of Gapan, Nueva Ecija Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija

Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija- Malolos, Bulacan

Baliuag, Bulacan

Baliuag, Bulacan

Bulakan, Bulacan

Bulakan, Bulacan

- Antipolo, Rizal

.jpg)

Liliw, Laguna

Liliw, Laguna

Majayjay, Laguna

Majayjay, Laguna

Paete, Laguna

Paete, Laguna Pagsanjan, Laguna

Pagsanjan, Laguna

Pangil, Laguna

Pangil, Laguna

- Sariaya, Quezon

Lucban, Quezon

Lucban, Quezon Tayabas, Quezon

Tayabas, Quezon- Mulanay, Quezon

Bacoor, Cavite

Bacoor, Cavite- Imus, Cavite

- Maragondon, Cavite

- Tagaytay, Cavite

See also

References

- "EAST & SOUTHEAST ASIA :: PHILIPPINES". CIA Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved Mar 29, 2018.

- "Tagalog, tagailog, Tagal, Katagalugan". English, Leo James. Tagalog-English Dictionary. 1990.

- Roberts, Edmund (1837). Embassy to the Eastern Courts of Cochin-China, Siam and Muscat. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 59.

- Ocampo, Ambeth (2012). Looking Back 6: Prehistoric Philippines. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Anvil Publishing, Inc. pp. 51–56. ISBN 978-971-27-2767-2.

- "The Laguna Copperplate Inscription Archived 2014-11-21 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed September 04, 2008.

- Postma, Antoon (June 27, 2008). "The Laguna Copper-Plate Inscription: Text and Commentary". Philippine Studies. 40 (2): 182–203.

- Morrow, Paul (2006-07-14). "Laguna Copperplate Inscription" Archived 2008-02-05 at the Wayback Machine. Sarisari etc.

- Scott 1984

- Pusat Sejarah Brunei Archived 2015-04-15 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved February 07, 2009.

- Sonia M. Zaide, Gregorio F. Zaide, pp. 69

- Chinese Muslims in Malaysia, History and Development by Rosey Wang Ma

- Pigafetta, Antonio (1969) [1524]. "First voyage round the world". Translated by J.A. Robertson. Manila: Filipiniana Book Guild. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Doctrina Cristiana". Project Gutenberg.

- Blair 1911, pp. 173–174

- The Philippines was an autonomous Captaincy-General under the Viceroyalty of New Spain from 1521 until 1815

- Spieker-Salazar, Marlies (1992). "A contribution to Asian Historiography : European studies of Philippines languages from the 17th to the 20th century". Archipel. 44 (1): 183–202. doi:10.3406/arch.1992.2861.

- Juan José de Noceda, Pedro de Sanlucar, Vocabulario de la lengua tagala, Manila 2013, pg iv, Komision sa Wikang Filipino

- Vocabulario de la lengua tagala, Manila 1860 at Google Books

- Juan José de Noceda, Pedro de Sanlucar, Vocabulario de la lengua tagala, Manila 2013, Komision sa Wikang Filipino.

- Cruz, H. (1906). Kun sino ang kumathâ ng̃ "Florante": kasaysayan ng̃ búhay ni Francisco Baltazar at pag-uulat nang kanyang karunung̃a't kadakilaan. Libr. "Manila Filatélico,". Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- Borah, Eloisa Gomez (2008-02-05). "Filipinos in Unamuno's California Expedition of 1587". Amerasia Journal. 21 (3): 175–183. doi:10.17953/amer.21.3.q050756h25525n72.

- "400th Anniversary Of Spanish Shipwreck / Rough first landing in Bay Area". SFGate. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- Espina, Marina E (1988-01-01). Filipinos in Louisiana. New Orleans, La.: A.F. Laborde. OCLC 19330151.

- Guererro, Milagros; Encarnacion, Emmanuel; Villegas, Ramon (1996), "Andrés Bonifacio and the 1896 Revolution", Sulyap Kultura, 1 (2): 3–12

- Guererro, Milagros; Schumacher, S.J., John (1998), Reform and Revolution, Kasaysayan: The History of the Filipino People, 5, Asia Publishing Company Limited, ISBN 978-962-258-228-6

- Guerrero, Milagros; Encarnacion, Emmanuel; Villegas, Ramon (2003), "Andrés Bonifacio and the 1896 Revolution", Sulyap Kultura, 1 (2): 3–12

- Guerrero, Milagros; Schumacher, S.J., John (1998), Reform and Revolution, Kasaysayan: The History of the Filipino People, 5, Asia Publishing Company Limited, ISBN 978-962-258-228-6

- Miguel de Unamuno, "The Tagalog Hamlet" in Rizal: Contrary Essays, edited by D. Feria and P. Daroy (Manila: National Book Store, 1968).

- Kabigting Abad, Antonio (1955). General Macario L. Sakay: Was He a Bandit or a Patriot?. J. B. Feliciano and Sons Printers-Publishers.

- 1897 Constitution of Biak-na-Bato, Article VIII, Filipiniana.net, archived from the original on 2009-02-28, retrieved 2008-01-16

- 1935 Philippine Constitution, Article XIV, Section 3, Chanrobles Law Library, retrieved 2007-12-20

- Manuel L. Quezon III, Quezon's speech proclaiming Tagalog the basis of the National Language (PDF), quezon.ph, retrieved 2010-03-26

- Andrew Gonzalez (1998), "The Language Planning Situation in the Philippines" (PDF), Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 19 (5, 6): 487–488, doi:10.1080/01434639808666365, retrieved 2007-03-24.

- 1973 Philippine Constitution, Article XV, Sections 2–3, Chanrobles Law Library, retrieved 2007-12-20

- Gonzales, A. (1998). Language planning situation in the Philippines. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 19(5), 487–525.

- Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. 2012. ISBN 978-1-59884-659-1.

- "Lowland Cultural Group of the Tagalogs". National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Archived from the original on 2014-07-14.

- Radio Television Malacañang. "Corazon C. Aquino, First State of the Nation Address, July 27, 1987" (Video). RTVM. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- "100% Pinoy: Pinoy Panghimagas". (2008-07-04). [Online video clip.] GMA News. Retrieved 2009-12-13.

- Filipino Fried Steak – Bistek Tagalog Recipe Archived April 12, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- https://www.aswangproject.com/philippines-monster-islands/

- https://www.aswangproject.com/soul-according-ethnolinguistic-groups-philippines/

- https://www.tagaloglang.com/pangangaluluwa/

- http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/647988/pangangaluluwa-reviving-a-dying-custom

- https://vanwinkles.com/11-mythical-sleep-creatures-from-around-the-world

- https://www.aswangproject.com/laho-moon-eater/

- http://cnnphilippines.com/life/culture/2019/01/22/Filipinos-astronomy-beliefs.html

- Tacio, Henrylito D. Death Practices Philippine Style Archived 2010-01-25 at the Wayback Machine, sunstar.com, October 30, 2005

- http://journals.upd.edu.ph/index.php/asp/article/viewFile/3961/3606

- https://www.aswangproject.com/bathala/

- https://www.aswangproject.com/beautiful-history-symbolism-philippine-tattoo-culture/

- Leticia Ramos Shahani, Fe B. Mangahas, Jenny R. Llaguno, pp. 27, 28, 30

- https://sites.google.com/site/philmyths/lesson-2

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/kristinakillgrove/2018/02/26/archaeologists-find-deformed-dog-buried-near-ancient-child-in-the-philippines/#4b89765d3897

- https://filipiknow.net/prehistoric-animals-in-the-philippines/

- tribhanga Archived January 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- http://asj.upd.edu.ph/mediabox/archive/ASJ-01-01-1963/Francisco%20Buddhist.pdf

- Prehispanic Source Materials: for the study of Philippine History" (Published by New Day Publishers, Copyright 1984) Written by William Henry Scott, Page 68.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Ramos-Shahani, L., Mangahas, Fe., Romero-Llaguno, J. (2006). Centennial Crossings: Readings on Babaylan Feminism in the Philippines. C & E Publishing.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Blair, E. H., Robertson, J. A., Bourne, E. G. (1906). The Philippine Islands, 1493-1803. AH Clark Company

- Cole, M. C. (1916). Philippine Folk Tales . Chicago: A.C. McClurg and Co. .

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Calderon, S. G. (1947). Mga alamat ng Pilipinas. Manila : M. Colcol & Co.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Ramos, M. (1990). Philippine Myths, Legends, and Folktales. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

- Calderon, S. G. (1947). Mga alamat ng Pilipinas. Manila : M. Colcol & Co.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Calderon, S. G. (1947). Mga alamat ng Pilipinas. Manila : M. Colcol & Co.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Ramos-Shahani, L., Mangahas, Fe., Romero-Llaguno, J. (2006). Centennial Crossings: Readings on Babaylan Feminism in the Philippines. C & E Publishing.

- Plasencia, J. (1589). Relacion de las Costumbres de Los Tagalos.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Demetrio, F. R., Cordero-Fernando, G., & Zialcita, F. N. (1991). The Soul Book. Quezon City: GCF Books.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- San Buenaventura, P. (1613). Vocabulario de Lengua Tagala.

- Scott, W. H. (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-century Philippine Culture and Society. Ateneo University Press.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Plasencia, J. (1589). Relacion de las Costumbres de Los Tagalos.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Calderon, S. G. (1947). Mga alamat ng Pilipinas. Manila : M. Colcol & Co.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Ramos, M. (1990). Philippine Myths, Legends, and Folktales. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Plasencia, J. (1589). Relacion de las Costumbres de Los Tagalos.

- Demetrio, F. R., Cordero-Fernando, G., & Zialcita, F. N. (1991). The Soul Book. Quezon City: GCF Books.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Souza, G. B., Turley, J. S. (2016). The Boxer Codex: Transcription and Translation of an Illustrated Late Sixteenth-century Spanish Manuscript Concerning the Geography, Ethnography and History of the Pacific, South-East Asia and East Asia. Brill.

- Potet, J. P. G. (2017). Ancient Beliefs and Customs of the Tagalogs. Morrisville, North Carolina: Lulu Press.

- Demetrio, F. R., Cordero-Fernando, G., & Zialcita, F. N. (1991). The Soul Book. Quezon City: GCF Books.

- Demetrio, F. R., Cordero-Fernando, G., & Zialcita, F. N. (1991). The Soul Book. Quezon City: GCF Books.

- Boquet, Y. (2017). The Philippine Archipelago: The Spanish Creation of the Philippines: The Birth of a Nation. Springer International Publishing.

- Boquet, Y. (2017). The Philippine Archipelago: A Tropical Archipelago. Springer International Publishing.

- Boquet, Y. (2017). The Philippine Archipelago: A Tropical Archipelago. Springer International Publishing.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Plasencia, J. (1589). Customs of the Tagalogs.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Kintanar, T. B., Abueva, J. V. (1996). The University of the Philippines cultural dictionary for Filipinos. University of the Philippines Press.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Kintanar, T. B., Abueva, J. V. (1996). The University of the Philippines cultural dictionary for Filipinos. University of the Philippines Press.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- Fansler, D. S. (1922). Manuscript Collection on Philippine Folktakes.

- Fansler, D. S. (1922). Manuscript Collection on Philippine Folktakes.

- Fansler, D. S. (1921). 1965 Filipino Popular Tales. Hatboro, Pennsylvania: Folklore Assosciates Inc.

- Ramos-Shahani, L., Mangahas, Fe., Romero-Llaguno, J. (2006). Centennial Crossings: Readings on Babaylan Feminism in the Philippines. C & E Publishing.

- Fansler, D. S. (1921). 1965 Filipino Popular Tales. Hatboro, Pennsylvania: Folklore Assosciates Inc.

- Ramos-Shahani, L., Mangahas, Fe., Romero-Llaguno, J. (2006). Centennial Crossings: Readings on Babaylan Feminism in the Philippines. C & E Publishing.

- Souza, G. B., Turley, J. S. (2016). The Boxer Codex: Transcription and Translation of an Illustrated Late Sixteenth-century Spanish Manuscript Concerning the Geography, Ethnography and History of the Pacific, South-East Asia and East Asia. Brill.

- Souza, G. B., Turley, J. S. (2016). The Boxer Codex: Transcription and Translation of an Illustrated Late Sixteenth-century Spanish Manuscript Concerning the Geography, Ethnography and History of the Pacific, South-East Asia and East Asia. Brill.

- Potet, J. P. G. (2017). Ancient Beliefs and Customs of the Tagalogs. Morrisville, North Carolina: Lulu Press.

- Potet, J. P. G. (2017). Ancient Beliefs and Customs of the Tagalogs. Morrisville, North Carolina: Lulu Press.

- Romulo, L. (2019). Filipino Children's Favorite Stories. China: Tuttle Publishing, Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

- San Buenaventura, P. (1613). Vocabulario de Lengua Tagala.

- San Buenaventura, P. (1613). Vocabulario de Lengua Tagala.

- Romulo, L. (2019). Filipino Children's Favorite Stories. China: Tuttle Publishing, Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

- Romulo, L. (2019). Filipino Children's Favorite Stories. China: Tuttle Publishing, Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

- Romulo, L. (2019). Filipino Children's Favorite Stories. China: Tuttle Publishing, Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

- Romulo, L. (2019). Filipino Children's Favorite Stories. China: Tuttle Publishing, Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

- Eugenio, D. L. (2013). Philippine Folk Literature: The Legends. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press

- Eugenio, D. L. (2013). Philippine Folk Literature: The Legends. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press

- Eugenio, D. L. (2013). Philippine Folk Literature: The Legends. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press

- Pulhin J. M., Tapoa M. A. (2005). History of A Legend: Managing the Makiling Forest Reserve. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

- Colin, F. (1663). Labor Evangelica de la Compañia de Jesus, en los Islas Filipinas. Madrid.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- San Buenaventura, P. (1613). Vocabulario de Lengua Tagala.

- Potet, J. P. G. (2017). Ancient Beliefs and Customs of the Tagalogs. Morrisville, North Carolina: Lulu Press.

- Scalice, J. (2018). Pamitinan and Tapusi: Using the Carpio legend to reconstruct lower-class consciousness in the late Spanish Philippines. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies

- Pardo, F. (1686-1688). Carte [...] sobre la idolatria de los naturales de la provincia de Zambales, y de los del pueblo de Santo Tomas y otros cicunvecinos [...]. Sevilla, Spain: Archivo de la Indias.

- Beyer, H. O. (1912–30). H. Otley Beyer Ethnographic Collection. National Library of the Philippines.

- Beyer, H. O. (1912–30). H. Otley Beyer Ethnographic Collection. National Library of the Philippines.

- Fansler, D. S. (1922). Manuscript Collection on Philippine Folktakes.

- Eugenio, D. L. (2007). Philippine Folk Literature. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press

- Eugenio, D. L. (2007). Philippine Folk Literature. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press

- Eugenio, D. L. (2013). Philippine Folk Literature: The Legends. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press