Operation Loyton

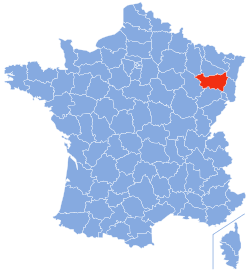

Operation Loyton was the codename given to a Special Air Service (SAS) mission in the Vosges department of France during the Second World War.

The mission, between 12 August and 9 October 1944, had the misfortune to be parachuted into the Vosges Mountains, at a time when the German Army was reinforcing the area, against General George Patton's Third Army. As a result, the Germans quickly became aware of their presence and conducted operations to destroy the SAS team.

With their supplies running out and under pressure from the German army, the SAS were ordered to form smaller groups to return to Allied lines. During the fighting and breakout operations 31 men were captured and later executed by the Germans.

Background

The Vosges is a region in north-eastern France close to the German border. In 1944 it was sparsely populated and consisted of wood covered hills, valley pastures and small isolated villages, an ideal area for a small mobile raiding force to operate.[1] In late 1944 it was also the area that General George Patton's Third Army was heading towards, but outrunning their supplies they had stopped at Nancy.[1] To counter the American advance the Germans had moved reinforcements, including the 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division Götz von Berlichingen, into the area.[2]

Mission

A small SAS advance party commanded by Captain Henry Druce was parachuted into the Vosges on 12 August 1944. The drop zone was in a deeply wooded mountainous area 40 miles (64 km) west of Strasbourg. The advance party's objective was to contact the local French resistance, carry out a reconnaissance of the area, identify targets for an attack and locate a suitable dropping zone for the main force.[3]

The main party under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Brian Franks arrived 18 days after the advance party on 30 August 1944. Their landing was not without incident. A parachute equipment container filled with ammunition exploded on contact with the ground.[1] A member of the resistance assisting to move the parachute containers killed himself by eating plastic explosive, believing it was some sort of cheese.[2] A Frenchman who was found in the area supposedly picking mushrooms, who the resistance believed was an informer, was detained. In the confusion following the explosion of the ammunition container, he managed to snatch up a Sten gun and was shot trying to escape.[4]

The following day the SAS started patrolling and set up observation posts. Almost immediately they became aware that their presence had been betrayed to the Germans.[3] There were far more Germans in the area than they expected and a force of 5,000 Germans were advancing up a valley near the village of Moussey just a short distance from the SAS base camp.[2] The SAS's aggressive patrolling, sabotage attacks and the number of fire fights they had engaged in, led the Germans to believe they were up against a far larger force than there actually was.[2] Over two nights, the 19 and 20 September, reinforcements were parachuted in which consisted of six Jeeps and another 20 men. The Jeeps, armed with Vickers K and Browning machine guns, allowed the SAS to change their tactics.[5] The Jeep patrols shot up German road convoys and staff cars. A patrol under the command of Captain Druce even entered Moussey, just as a Waffen SS unit was assembling. Driving through the town, they opened fire and inflicted many casualties.[3]

The Germans, unable to locate the SAS base, were aware that they could not be operating without the assistance of the local population. To gain information about the location of the SAS camp, all the male residents of Moussey between the ages of 16 and 60, a total of 210 men, were arrested.[5] After being interrogated they were transported to concentration camps, from which only 70 returned after the war.[5] On 29 September 1944 Captain Druce was sent to cross back over into the American lines, with the order of battle for a Panzer division which had been obtained by a member of the resistance. Initially with F/O Fiddick, R.C.A.F 622 Sqn, but alone on the second and third occasions, Druce passed through the German lines three times before eventually reaching safety.[3][6]

At the start of October, with Patton's army stalled and supplies running out, the likelihood that the Americans would relieve the SAS had dwindled. It was decided to end the operation, which had only been intended to last two weeks and had now lasted over two months. Lieutenant Colonel Franks ordered his forces to split up into small groups and make their own way back to the Allied lines 40 miles (64 km) away. One patrol was ambushed by the Waffen-SS, killing three men. The fourth, Lieutenant Peter Johnsen, was wounded but managed to escape. Another 34 men failed to reach Allied lines.[7]

Aftermath

At the end of the war Franks began investigating the fate of his missing men. All that was known for certain was that three men accompanying Lieutenant Johnsen had been killed, and that 10 men had been buried in the cemetery at Moussey.[7] The SAS was officially disbanded in October 1945. Prior to this the 2nd SAS War Crimes Investigation Team (2 SAS WCIT) had been formed to, amongst other things, look into the events after Loyton.[8] 2nd SAS Intelligence Officer Major Eric 'Bill' Barkworth had been informed of the existence of the Commando Order, which called for the execution of all captured commandos when he was interviewing captured German officers in 1944.[9] In July 1945 Franks was informed by the French that the bodies of some SAS men had been found in the French occupation zone at Gaggenau.[10] Franks ordered 2 SAS WCIT, under the command of Major Beckworth, to travel to the area. Their investigation discovered that of the 31 missing SAS men, 30 had been murdered by the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), some of them at the Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp in the Vosges mountains. One man's fate was never discovered.[11]

Erich Isselhorst, head the Sicherheitspolizei in Strasbourg, was sentenced to death by a British military tribunal in June 1946 for the murder of the British POWs but handed over to the French. He was once more sentenced to death in May 1947, now by a French military tribunal, and executed in Strasbourg on 23 February 1948.[12][13] While posted in Strasbourg, Isselhorst was part of the Operation Waldfest, a scorched earth operation in which villages in Alsace and Lorraine were destroyed to eliminate shelter for Allied troops for the upcoming winter and inhabitants deported as forced labour or to concentration camps. In a coordinated operation by the Wehrmacht and SS, villages were raided, French resistance fighters and the captured SAS soldiers were executed.[14]

Isselhorst ordered the execution of the captured British SAS members, as well as a number of French civilians, three French priests and four US airmen. The prisoners were taken over the Rhine river on trucks to Gaggenau on 21 November 1944. The leader of the execution commando, Karl Beck, thought it unwise to leave mass graves of shot allied soldiers in an area so close to the front line. The prisoners were initially kept in a local jail but then, on or shortly after 25 November, unaware of their fate, taken to a local forest and, in groups of three, shot in the head in a bomb crater. One prisoner attempted to escape but was killed as well. Apart from Isselhorst, his second in command, Wilhelm Schneider was also executed for the war crime in January 1947. Beck initially escaped punishment but was sentenced to death in the 1950s.[15]

In 2003 a memorial was erected at Moussey to commemorate those who had been murdered. It details the three men from Phantom, the 31 SAS men, the 140 French civilians and one British and two French service women of the Special Operations Executive that had also been caught up in the search for the SAS camp.[16] A memorial to the operation also exists at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire.[17]

References

- Notes

- Schorley & Forsyth, p. 44.

- Schorley & Forsyth, p. 45.

- "Obituary:Henry Druce". Daily Telegraph. London. 7 February 2007. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- Schorley & Forsyth, pp. 44–45.

- Schorley & Forsyth, p. 46.

- National Archives (UK), Catalogue Reference WO/208/3324

- Schorley & Forsyth, p. 47.

- Charlesworh, p. 17.

- Charlesworth, p. 18.

- Charlesworth, p. 24.

- Charlesworth, p. 25.

- Lilla, Joachim. "Isselhorst, Erich" (in German). Bavarian State Library. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- "Isselhorst Erich (1906-1948)". Yad Vashem. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- "Aktion Waldfest" (in German). Gedenkorte Europa. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- Jones 2016, pp. 265–267.

- Schorley & Forsyth, p. 50.

- "Obituary: Len Owens". The Daily Telegraph. 2 July 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- Bibliography

- Schorley, Pete; Forsyth, Frederick (2008). Who Dares Wins: Special Forces Heroes of the SAS. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84603-311-X.

- Charlesworth, Laurie (2006). "The Journal of Intelligence History, Volume 6, Number 2". LIT Verlag Münster. ISSN 1616-1262. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Jones, Benjamin F. (2016). Eisenhower's Guerrillas: The Jedburghs, the Maquis, and the Liberation of France. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199942084.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)