Operation Undergo

Operation Undergo was an attack by the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division on the German garrison and fortifications of the French port of Calais, during September 1944. A subsidiary operation was executed to capture German long-range, heavy artillery at Cap Gris Nez, which threatened the sea approaches to Boulogne. The operation was part of the Clearing the Channel Coast undertaken by the First Canadian Army, following the victory of Operation Overlord and the break-out from Normandy. The assault on Calais used the tactics of Operation Wellhit at Boulogne, sealing the town, bombardments from land, sea and air, followed by infantry assaults supported by armour, including flame-throwing tanks and creeping barrages.

The city had been declared a fortress (Festung) but when pressed, its second-rate garrison needed little persuasion to surrender. This reluctance to fight to the end was repeated at Cap Gris Nez. The 7th and 8th Canadian Infantry Brigades started the main attack from south-west of Calais and cleared the outer defences on the southern and western sides of the port. The 8th Canadian Brigade was then transferred to the eastern side and the inner defensive lines were attacked from both sides. The Germans called for a truce which, after some misunderstanding, led to an unconditional surrender of the garrison. The 9th Brigade took the heavy batteries on Cap Gris Nez at the same time.

Background

Allied break-out

In northern France, all German armed forces (Wehrmacht) retreated after the disaster at Falaise and the Allied break-out. There were no reserve defences to fall back on, as Adolf Hitler had forbidden their construction. The rapid Allied advances into eastern France and through Belgium stretched Allied supply lines and the capture of ports for supply was the task given to the First Canadian Army by General Bernard Montgomery, who judged that he needed the Channel ports of Le Havre, Dieppe, Boulogne, Calais and Dunkirk to supply the 21st Army Group, if an attempt was to be made to advance into Germany without opening Antwerp first. Most of the ports had been fortified and were to be held by their garrisons for as long as possible.[1]

After his surrender, the fortress commander, Oberstleutnant Ludwig Schroeder, called the garrison, consisting of 7,500 sailors, airmen and soldiers, of whom only 2,500 were fit for use as infantry, "mere rubbish". Many of the garrison troops were Volksdeutsche ("ethnic Germans" born in foreign countries) and Hiwis (foreign volunteers); morale was low and the troops were susceptible to Allied propaganda. A report of the post battle interrogations of prisoners concluded that,

Army personnel were old, ill, and lacked both the will to fight and to resist interrogation; naval personnel were old and were not adjusted to land warfare; only the air force A.A. gunners showed any sign of good morale and were also the only youthful element of the whole garrison.[1]

Schroeder was judged by his interrogators as a "mediocre and accidental" leader, who became commander by coincidence.[1]

Terrain

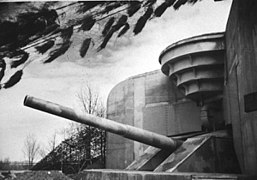

The French coast goes northwards from Boulogne and turns sharply at Cap Gris Nez to a line roughly south to north-east, which continues beyond the Belgian border. There are no large natural harbours but important docks have been formed in the low-lying land at Calais. The landscape around Cap Gris Nez and Cap Blanc Nez nearby, is a continuation of the rolling rural Boulonnais hills, Calais is on the coastal edge of a low flat plain drained by the River Aa and man-made watercourses. The city had been fortified for centuries; the defences were used by the British and French in the Siege of Calais in June 1940 and were added to the German Atlantic Wall coastal defence system built after 1940.[2] In 1944 the Germans had 42 heavy guns in the vicinity of Calais, including five batteries of cross-channel guns, Batterie Lindemann (four 406 mm guns at Sangatte), Batterie Wissant (150 mm guns near Wissant), Batterie Todt (four 380 mm guns), Grosser Kurfurst (four 280 mm guns) and Gris Nez (three 170 mm guns).[3] The Germans had broken the drainage systems, flooding the hinterland and added large barbed wire entanglements, minefields and blockhouses.[2]

Prelude

The Allies judged it essential to silence the German heavy coastal batteries around Calais which could threaten Boulogne-bound shipping and bombard Dover and inland targets.[4] Spry devised a plan similar to Operation Wellhit, the capture of Boulogne, earlier in September. A bombardment from land, sea and air was to "soften up" the defenders, even if it failed to destroy the defences. Infantry assaults would follow, preceded by local bombardments to keep the defenders under cover until too late to be effective and accompanied by Churchill Crocodile and Wasp flame-throwing vehicles to act as final "persuaders". Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers would be used to deliver infantry as close to their objectives as possible.

The assaults were planned to approach Calais from the west and south-west, avoiding the worst inundations and the main urban areas. The attack of the 8th Canadian Brigade from the west was against the positions at Escalles, near Cape Blanc Nez and Noires Mottes. The 7th Canadian Brigade was to assault the garrisons of Belle Vue, Coquelles and Calais. The eastern side of the city was screened by The Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa to prevent a break-out; the 9th Canadian Brigade would take over from the 7th Reconnaissance Regiment at Cape Gris Nez and prepare to capture the batteries there.

Montgomery had been directed to bring Antwerp into operation and pressed Crerar quickly to capture the Channel Ports. Crerar recognised the considerable effort being used to capture the ports and the time needed to bring them back into use. Having obtained the Royal Navy's views he decided that he was prepared to accept the "masking" (isolating the enemy garrison with a reduced force) of Calais and redeployment of the troops and equipment to Antwerp, a more significant port but this was not passed on to Spry, who continued with the assault on Calais.[5]

Battle

Wissant

The 7th Canadian Brigade had sealed off Calais in early September and the Regina Rifles captured the coastal town of Wissant, isolating the Cap Gris Nez batteries from Calais and took Batterie Wissant with its four 150 mm guns. This success prompted Spry to attack Cap Gris Nez with two battalions but the attempt failed and the area was left for later.[2]

Calais

The 7th and 8th Canadian Infantry Brigades opened their attack on Calais and its western coastal defences at 10:15 a.m., on 25 September after a day's delay, following preparatory air and artillery bombardments.[6] The Régiment de la Chaudière were to advance through Escalles, taking Cap Blanc Nez and link up near Sangatte with the North Shore Regiment. The North Shores had the difficult task of taking the fortified Noires Mottes, high ground near Sangatte and the site of Batterie Lindemann. To shield Canadian activity around Cap Blanc Nez and Calais from observation and interference from the batteries at Cap Gris Nez, a large smoke screen was established along a 3 km (1.9 mi) line inland from Wissant, for five days.[7] The capture of Cap Blanc Nez proved to be unexpectedly easy. As soon as the Chaudieres' assault reached the first defences, the garrison offered to surrender. This was completed just two hours later, most defenders reportedly being dead drunk.[2][6]

The North Shores' attack on Noires Mottes was supported by flail tanks from the 79th Armoured Division and gunfire from the 10th Armoured Regiment on the approach through minefields and by Crocodiles to reduce fortifications. Early attempts by small groups of Germans to surrender were discouraged when they were shot down by their own side.[8] The advance was held up by the defenders and bomb craters that obstructed the Crocodiles before nightfall. Negotiations were opened with the help of German prisoners and the Noires Mottes garrison surrendered at first light on the following morning, 26 September. A formidable defensive position and nearly 300 prisoners had been captured cheaply; the Sangatte battery was also surrendered.[6][9] Examination of the forts showed that they had been extensively booby-trapped.[8]

The early success of the 8th Canadian Brigade had captured ground that overlooked the attack front of the 7th Canadian Brigade, which greatly helped the attacks on the Belle Vue Ridge and Coquelles. The 1st Canadian Scottish, the Regina Rifles and The Royal Montreal Regiment were to attack through the Belle Vue fortifications to the seafront just east of Sangatte. At first, following closely the creeping artillery barrage, the Canadians overran the first defences. Much had been missed by the bombardment and the Reginas suffered many casualties until the reserves, the Canadian Scots and flame-throwing Crocodiles overcame the defenders. The 8th Canadian Brigade reached Sangatte on the morning of 26 September, with its objectives complete, it was transferred to the eastern side, relieved the Camerons and applied pressure from another direction.[10][11]

The next stages would be the 7th Canadian Brigade advance through Coquelles and flooded ground to Fort Nieulay and a frontal attack on Calais by the Regina Rifles, following a railway by boat across more flooded ground to the south-west of the city's factory area. These advances were difficult, the defenders held their ground and had to be overrun step-by-step. The Canadian Scots were ordered to make a night attack along the coast to Fort Lapin. On 27 September, the Canadians withdrew temporarily during an attack by heavy bombers on German strongpoints. Fort Lapin fell only after further air attacks and support from tanks and flame-throwing tanks.[12] The Winnipegs, again assisted by flame-throwing tanks, captured Fort Nieulay and the Reginas reached their immediate target, the factory district.[13]

Further advances were made by the 7th Canadian Brigade on 28 September but two companies of the Canadian Scots, having crossed the canal protecting Calais' western side, were pinned down and cut off until the truce. Plans were in hand for further crossings into the city when Schroeder requested that Calais be declared an open city. This was rejected as a delaying tactic but a truce was agreed on 29 September to allow the safe evacuation of 20,000 civilians.[13] Plans were laid for an attack on Calais supported by more air attacks as soon as the truce expired at noon on 30 September.[14]

The Canadians attacked immediately after the truce expired, despite German attempts to surrender; Crerar said that "the Hun, if they wished to quit, could march out with their hands up, without arms, and flying white flags in the normal manner". Schroeder had ordered the garrison to cease resistance and the 7th Canadian Brigade, entering from the west, met no opposition, German troops surrendering everywhere. It required a Canadian officer, Lt Colonel P. C. Klaehn (C.O. of the Cameron Highlanders), at some personal risk, to enter Calais during an artillery bombardment to accept the formal surrender. Schroeder left Calais at 7:00 p.m. and went into captivity.[15]

Cap Gris Nez

The first attempt by elements of the 7th Canadian Brigade to take Cap Gris Nez from 16 to 17 September failed; the brigade was redeployed for its role at Calais and it was replaced by the 7th Reconnaissance Regiment until a stronger force was available.[16] The 9th Canadian Brigade, with armoured support from the 1st Hussars (6th Armoured Regiment) and flail tanks, Churchill Crocodiles and Armoured Vehicle Royal Engineers (AVRE) from the 79th Armoured Division, was deployed to Cap Gris Nez to take the three remaining heavy batteries. On the right, The Highland Light Infantry of Canada (HLI) would attack the two northern batteries, Grosser Kürfurst at Floringzelle and Gris Nez about 1.25 km (1 mi) south-east of Cap Gris Nez. On the left, The North Nova Scotia Highlanders (NNS) faced Batterie Todt at Haringzelles, 2 km (1.2 mi) south of Batterie Grosser Kürfurst. On the landward side, the guns were protected by minefields, barbed wire, blockhouses and anti-tank positions.[17]

The infantry were preceded by attacks by 532 aircraft from RAF Bomber Command on 26 September and by 302 bombers on 28 September. Although these probably weakened the defences as well as the defenders' will to fight, cratering of the ground impeded the use of armour, causing tanks to bog down. Accurate shooting by Winnie and Pooh, British heavy guns at Dover, disabled Batterie Grosser Kürfurst.[18] The battery had fired inland and caused some casualties among the British artillery assembled inland of Wissant, despite the smokescreen.[19]

On 29 September, artillery opened fire at 6:35 a.m. and the infantry attack began after ten minutes minutes behind a creeping barrage that kept the defenders under cover. The Germans readily surrendered once the attackers were among them. The HLI had captured Batterie Grosser Kurfurst by 10:30 a.m., fewer than three hours from H-Hour and Gris Nez was taken during the afternoon. The NNS encountered even less resistance, reaching the gun houses without opposition. The concrete walls were impervious even to AVRE petard mortars but their noise and concussion, along with hand grenades thrown into embrasures, induced the German gunners to surrender by mid-morning. The NNS continued on to capture the local German headquarters at Cran-aux-Oeufs.[20] Despite the impressive German fortifications, the defenders refused to fight on and the operation was concluded at relatively low cost in casualties.[21]

Aftermath

The damage to the port was severe and the facilities were not available until November, after Antwerp had been opened. Even then, traffic was limited to personnel.[3] The reduction of the German heavy coastal batteries allowed use of Boulogne; mine-sweeping had commenced within hours of the success of the 9th Canadian Brigade. The capture of the German guns on Cap Gris Nez ended four years of artillery exchanges. Dover suffered its last bombardment on 26 September and the mayor was sent a German flag from the batteries to mark the event.[22]

The Canadians were criticised for their performance at Calais and the other Channel ports; their progress was compared unfavourably with that of other Allied units. Montgomery commented that the Canadian Army had been "badly handled and very slow". Montgomery had a low opinion of Crerar and there has been speculation that Crerar's departure on sick leave was a euphemism for his removal from command. His replacement, the energetic Guy Simonds, was much preferred by Montgomery and he commanded the forces that cleared the approaches to Antwerp.[23]

The commander of 84 Group, RAF, Air Vice Marshal Leslie Brown, displeased Air Marshal Sir Arthur Coningham by his close co-operation with the Canadian Army. Coningham wished to see the air force act independently, not in close co-operation with the army and looked for "someone less subservient to the army". Once Antwerp had been opened, he replaced Brown with Air-Vice Marshal Edmund Hudleston.[24]

Orders of battle

Allied

- Canadian 3rd Infantry Division (All data from Monahan, Appendix C (1947) unless specified.)[25]

- 7th Reconnaissance Regiment (17th Duke of York's Royal Canadian Hussars)

- The Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa (machine gun)

- 7th Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

- 12th Field Artillery Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

- 13th Field Artillery Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

- 14th Field Artillery Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

- 3rd Anti-tank Regiment

- 4th Light Anti-aircraft Regiment

- 16th Field Company

- 3rd Canadian Divisional Signals, Royal Canadian Corps of Signals

- No. 3 Defense and Employment Platoon (Lorne Scots)

- "C" Flight, 660 (Air Observation Post) Squadron, RAF

- 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade

- The Royal Winnipeg Rifles

- The Regina Rifle Regiment, less 1 company

- 1 company, Royal Montreal Regiment[10]

- 1st Battalion The Canadian Scottish Regiment

- 7 Canadian Infantry Brigade Ground Defence Platoon (Lorne Scots)

- 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade

- The Queen's Own Rifles of Canada

- Le Régiment de la Chaudière

- North Shore Regiment

- 8 Canadian Infantry Brigade Ground Defence Platoon (Lorne Scots)

- 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade

- The Highland Light Infantry of Canada

- The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders

- The North Nova Scotia Highlanders

- 9 Canadian Infantry Brigade Ground Defence Platoon (Lorne Scots)

Artillery

- 9th Army Group Royal Artillery

- 9th Medium Regiment Royal Artillery

- 10th Medium Regiment Royal Artillery

- 11th Medium Regiment Royal Artillery

- 107th Medium Regiment Royal Artillery

- 51st Heavy Regiment Royal Artillery

- 2nd Army Group Royal Canadian Artillery

- 3rd Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

- 4th Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery

- 15th Medium Regiment Royal Artillery

- 1st Heavy Regiment Royal Artillery

- "C" Flight, 661 (Air Observation Post) Squadron, RAF

Tanks and specialist vehicles

- 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade (part of)

- 6th Armoured Regiment (1st Hussars)

- 10th Armoured Regiment (The Fort Garry Horse)

- 79th Armoured Division (part of)

- 141st Regiment, Royal Armoured Corps (Churchill Crocodile (flamethrowing tanks)

- 6th Assault Regiment Royal Engineers (AVRE)

- 1st Lothians and Border Horse (flail tanks)

- "C" Squadron, 22nd Dragoons (flail tanks)

- 25th Canadian Armoured Delivery Regiment (The Elgins) (part of)

- 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron[lower-alpha 1]

- 51st (Highland) Infantry Division (part of)

- 12th Field Artillery Regiment, Royal Artillery

- 13th Field Artillery Regiment, Royal Artillery

- 14th Field Artillery Regiment, Royal Artillery

German garrison

- Luftwaffe anti-aircraft troops

- Kriegsmarine coastal battery detachments

- 242nd Naval Coastal Artillery Battalion (Cap Gris Nez)

- Infantry (various)

See also

- Cross-Channel guns in the Second World War

Notes

- The 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Squadron was the basis of the 1st Armoured Carrier Regiment, formed in October, 1944.

Footnotes

- Monahan 1947, p. 74.

- Copp 2006, p. 76.

- Stacey 1960, p. 352.

- Stacey 1960, pp. 346, 344.

- Copp 2006, pp. 75–76.

- Stacey 1960, p. 349.

- Copp 2006, p. 78.

- Wareing, James (23 April 2004). "Capture of the Cross Channel Guns at Sangatte 1944". WW2 People's War. BBC. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- Ellis 2004, p. 65.

- Copp 2006, p. 79.

- Stacey 1960, p. 350.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 65–66.

- Monahan 1947, p. 86.

- Monahan 1947, p. 88.

- Monahan 1947, p. 96.

- Stacey 1960, pp. 345–346.

- Stacey 1960, pp. 352–353.

- Copp 2006, p. 82.

- 9 AGRA nd; Stacey 1960, pp. 353–354.

- Stacey 1960, p. 353.

- Copp 2006, p. 82; Stacey 1960, p. 354.

- Roskill 2004, p. 137; Stacey 1960, p. 354.

- Copp 2006, pp. 82–83.

- Copp 2006a, p. 30.

- Monahan 1947, appendix C.

References

- Copp, Terry, ed. (2000). Montgomery's Scientists: Operational Research in Northwest Europe. The work of No.2 Operational Research Section with 21 Army Group June 1944 to July 1945. Waterloo, Ont: LCMSDS. ISBN 978-0-9697955-9-9.

- Copp, Terry (2006). Cinderella Army: The Canadians in Northwest Europe, 1944–1945. Toronto, Ont: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-3925-5.

- Copp, Terry (Spring 2006). "The Siege of Boulogne and Calais" (PDF). IX (1). The Canadian Army Journal: 30–48. ISSN 1713-773X. Retrieved 27 January 2018. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Ellis, Major L. F.; with Warhurst, Lieutenant-Colonel A. E. (2004) [1968]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). Victory in the West: The Defeat of Germany. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. II (pbk repr. Naval & Military Press, Uckfield ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-1-84574-059-7.

- Monahan, J. W. (1947). The Containing of Dunkirk (pdf). Canadian Participation in the Operations in North-west Europe 1944. Part V: Clearing the Channel Ports, 3 Sep 44 – 6 Feb 45 (Report). CMHQ Reports (184) (online ed.). Historical Section, Canadian Military Headquarters. OCLC 961860099. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- Roskill, S. (2004) [1961]. The War at Sea 1939–1945: The Offensive, Part II 1st June 1944 – 14th August 1945. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Service (pbk. repr. Naval & Military Press, Uckfield ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-1-84342-806-0.

- Stacey, Colonel C. P.; Bond, Major C. C. J. (1960). The Victory Campaign: The operations in North-West Europe 1944–1945 (pdf). Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War. III. The Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery Ottawa. OCLC 606015967. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- "The History of 9 Army Group Royal Artillery". Archived from the original on 7 August 2008. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

.svg.png)