Derry

Derry, officially Londonderry (/ˈlʌndəndɛri/),[5] is the second-largest city in Northern Ireland[6][7] and the fourth-largest city on the island of Ireland.[8] The name Derry is an anglicisation of the Old Irish name Daire (modern Irish: Doire [ˈd̪ˠɛɾʲə]) meaning "oak grove".[9][10] In 1613, the city was granted a Royal Charter by King James I and gained the "London" prefix to reflect the funding of its construction by the London guilds. While the city is more usually known colloquially as Derry,[11][12] Londonderry is also commonly used and remains the legal name.

| Derry/Londonderry | |

|---|---|

From top, left to right: Austin's Department Store, Derry's Walls, Free Derry Corner, Peace Bridge across the River Foyle, a view of Derry at night, Diamond War Memorial, 'Hands Across the Divide' sculpture | |

Vita Veritas Victoria "Life, Truth, Victory" (Adapted from a decoration on the Craigavon Bridge) | |

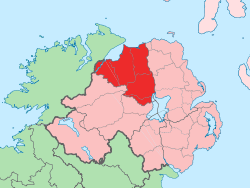

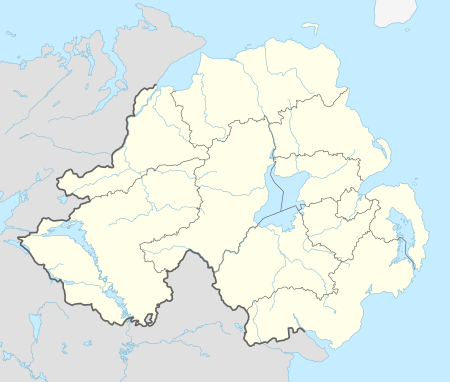

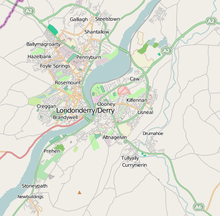

Location within Northern Ireland | |

| Population | 2008 est. |

| Irish grid reference | C434166 |

| District |

|

| County | |

| Country | Northern Ireland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDONDERRY[4] |

| Postcode district | BT47, BT48 |

| Dialling code | 028 |

| Police | Northern Ireland |

| Fire | Northern Ireland |

| Ambulance | Northern Ireland |

| UK Parliament | |

| NI Assembly | |

The old walled city lies on the west bank of the River Foyle, which is spanned by two road bridges and one footbridge. The city now covers both banks (Cityside on the west and Waterside on the east). The population of the city was 83,652 at the 2001 Census, while the Derry Urban Area had a population of 90,736.[13] The district administered by Derry City and Strabane District Council contains both Londonderry Port and City of Derry Airport.

Derry is close to the border with County Donegal, with which it has had a close link for many centuries. The person traditionally seen as the founder of the original Derry is Saint Colmcille, a holy man from Tír Chonaill, the old name for almost all of modern County Donegal, of which the west bank of the Foyle was a part before 1610.[14]

In 2013, Derry was the inaugural UK City of Culture, having been awarded the title in 2010.[15][16]

Name

According to the city's Royal Charter of 10 April 1662, the official name is "Londonderry". This was reaffirmed in a High Court decision in 2007 when Derry City Council sought guidance on the procedure for effecting a name change.[17][18] The council had changed its name from "Londonderry City Council" to "Derry City Council" in 1984;[19] the court case was seeking clarification as to whether this had also changed the name of the city. The decision of the court was that it had not but it was clarified that the correct procedure to do so was via a petition to the Privy Council.[20] Derry City Council afterward began this process, and was involved in conducting an equality impact assessment report (EQIA).[21] Firstly it held an opinion poll of district residents in 2009, which reported that 75% of Catholics and 77% of Nationalists found the proposed change acceptable, compared to 6% of Protestants and 8% of Unionists.[22] The EQIA then held two consultative forums, and solicited comments from the general public on whether or not the city should have its name changed to Derry.[23] A total of 12,136 comments were received, of which 3,108 were broadly in favour of the proposal, and 9,028 opposed to it.[23] On 23 July 2015, the council voted in favour of a motion to change the official name of the city to Derry and to write to Mark H. Durkan, Northern Ireland Minister of the Environment, to ask how the change could be effected.[24]

Despite the official name, the city is more usually known as "Derry",[11][12] which is an anglicisation of the Irish Daire or Doire, and translates as "oak-grove/oak-wood". The name derives from the settlement's earliest references, Daire Calgaich ("oak-grove of Calgach").[25] The name was changed from Derry in 1613 during the Plantation of Ulster to reflect the establishment of the city by the London guilds.[26][27]

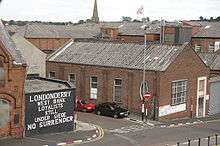

The name "Derry" is preferred by nationalists and it is broadly used throughout Northern Ireland's Catholic community,[28] as well as that of the Republic of Ireland, whereas many unionists prefer "Londonderry";[29] however, in everyday conversation "Derry" is used by most Protestant residents of the city.[30] Linguist Kevin McCafferty argues that "It is not, strictly speaking, correct that Northern Ireland Catholics call it Derry, while Protestants use the Londonderry form, although this pattern has become more common locally since the mid-1980s, when the city council changed its name by dropping the prefix". In McCafferty's survey of language use in the city, "only very few interviewees—all Protestants—use the official form".[31]

Apart from the name of Derry City Council, the city is usually[28] known as Londonderry in official use within the UK. In the Republic of Ireland, the city and county are almost always referred to as Derry, on maps, in the media and in conversation.[32] In April 2009, however, the Republic of Ireland's Minister for Foreign Affairs, Micheál Martin, announced that Irish passport holders who were born there could record either Derry or Londonderry as their place of birth.[33] Whereas official road signs in the Republic use the name Derry, those in Northern Ireland bear Londonderry (sometimes abbreviated to "L'Derry"), although some of these have been defaced with the reference to London obscured.[34] Usage varies among local organisations, with both names being used. Examples are City of Derry Airport, City of Derry Rugby Club, Derry City FC and the Protestant Apprentice Boys of Derry, as opposed to Londonderry Port, Londonderry YMCA Rugby Club and Londonderry Chamber of Commerce.[35] The bishopric has always remained that of Derry, both in the (Protestant, formerly-established) Church of Ireland (now combined with the bishopric of Raphoe), and in the Roman Catholic Church. Most companies within the city choose local area names such as Pennyburn, Rosemount or "Foyle" from the River Foyle to avoid alienating the other community. Londonderry railway station is often referred to as Waterside railway station within the city, but is called Derry/Londonderry at other stations. The council changed the name of the local government district covering the city to Derry on 7 May 1984, consequently renaming itself Derry City Council.[36] This did not change the name of the city, although the city is coterminous with the district, and in law the city council is also the "Corporation of Londonderry" or, more formally, the "Mayor, Aldermen and Citizens of the City of Londonderry".[37] The form "Londonderry" is used for the post town by the Royal Mail;[31] however, use of "Derry" will still ensure delivery.

The city is also nicknamed the Maiden City by virtue of the fact that its walls were never breached despite being besieged on three separate occasions in the 17th century, the most notable being the Siege of Derry of 1688–1689.[38] It was also nicknamed Stroke City by local broadcaster Gerry Anderson, owing to the politically correct use by some of the dual name Derry/Londonderry[28] (which has itself been used by BBC Television).[39] A recent addition to the landscape has been the erection of several large stone columns on main roads into the city welcoming drivers, euphemistically, to "the walled city".

The name Derry is very much in popular use throughout Ireland for the naming of places, and there are at least six towns bearing that name and at least a further 79 places. The word Derry often forms part of the place name, for example Derrybeg, Derryboy, Derrylea and Derrymore.

The names Derry and Londonderry spread from Ireland to the other colonies of the British Empire, frequently named by Scotch-Irish settlers. Londonderry, Yorkshire, near the Yorkshire Dales, was named for the Marquesses of Londonderry,[40] as are the Londonderry Islands off Tierra del Fuego in Chile. In North America, twin towns in New Hampshire called Derry and Londonderry lie not far from Londonderry, Vermont, with additional namesakes in Derry, Pennsylvania, Londonderry, Ohio, Londonderry, Nova Scotia and Londonderry, Edmonton (Alberta, Canada). There is also a Derry, New South Wales.

City walls

Derry is the only remaining completely intact walled city in Ireland, and one of the finest examples of a walled city in Europe.[41][42][43] The walls constitute the largest monument in State care in Northern Ireland and, as part of the last walled city to be built in Europe, stand as the most complete and spectacular.[44]

The Walls were built in 1613–1619 by The Honourable The Irish Society as defences for early 17th century settlers from England and Scotland. The Walls, which are approximately 1 mile (1.6 km) in circumference and which vary in height and width between 3.7 and 10.7 metres (12 and 35 feet), are completely intact and form a walkway around the inner city. They provide a unique promenade to view the layout of the original town which still preserves its Renaissance style street plan. The four original gates to the Walled City are Bishop's Gate, Ferryquay Gate, Butcher Gate and Shipquay Gate. Three further gates were added later, Magazine Gate, Castle Gate and New Gate, making seven gates in total.

It is one of the few cities in Europe that never saw its fortifications breached, withstanding several sieges, including the famous Siege of Derry in 1689 which lasted 105 days; hence the city's nickname, The Maiden City.[45]

History

Early history

Derry is one of the oldest continuously inhabited places in Ireland.[46] The earliest historical references date to the 6th century when a monastery was founded there by St Columba or Colmcille, a famous saint from what is now County Donegal, but for thousands of years before that people had been living in the vicinity.

Before leaving Ireland to spread Christianity elsewhere, Colmcille founded a monastery at Derry (which was then called Doire Calgach), on the west bank of the Foyle. According to oral and documented history, the site was granted to Colmcille by a local king.[47] The monastery then remained in the hands of the federation of Columban churches who regarded Colmcille as their spiritual mentor. The year 546 is often referred to as the date that the original settlement was founded. However, it is now accepted by historians that this was an erroneous date assigned by medieval chroniclers.[46] It is accepted that between the 6th century and the 11th century, Derry was known primarily as a monastic settlement.[46]

The town became strategically more significant during the Tudor conquest of Ireland and came under frequent attack. During O'Doherty's Rebellion in 1608 it was attacked by Sir Cahir O'Doherty, Irish chieftain of Inishowen, who burnt much of the town and killed the governor George Paulet.[48] The soldier and statesman Sir Henry Docwra made vigorous efforts to develop the town, earning the reputation of being " the founder of Derry"; but he was accused of failing to prevent the O'Doherty attack, and returned to England.

Plantation

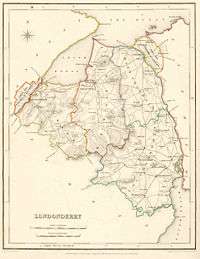

What became the City of Derry was part of the relatively new County Donegal up until 1610.[49] In that year, the west bank of the future city was transferred by the English Crown to The Honourable The Irish Society[49] and was combined with County Coleraine, part of County Antrim and a large portion of County Tyrone to form County Londonderry. Planters organised by London livery companies through The Honourable The Irish Society arrived in the 17th century as part of the Plantation of Ulster, and rebuilt the town with high walls to defend it from Irish insurgents who opposed the plantation. The aim was to settle Ulster with a population supportive of the Crown.[27] It was then renamed "Londonderry".

This city was the first planned city in Ireland: it was begun in 1613, with the walls being completed in 1619, at a cost of £10,757.[50] The central diamond within a walled city with four gates was thought to be a good design for defence. The grid pattern chosen was subsequently much copied in the colonies of British North America.[51] The charter initially defined the city as extending three Irish miles (about 6.1 km) from the centre.

The modern city preserves the 17th century layout of four main streets radiating from a central Diamond to four gateways – Bishop's Gate, Ferryquay Gate, Shipquay Gate and Butcher's Gate. The city's oldest surviving building was also constructed at this time: the 1633 Plantation Gothic cathedral of St Columb. In the porch of the cathedral is a stone that records completion with the inscription: "If stones could speake, then London's prayse should sound, Who built this church and cittie from the grounde."[52]

17th-century upheavals

During the 1640s, the city suffered in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which began with the Irish Rebellion of 1641, when the Gaelic Irish insurgents made a failed attack on the city. In 1649 the city and its garrison, which supported the republican Parliament in London, were besieged by Scottish Presbyterian forces loyal to King Charles I. The Parliamentarians besieged in Derry were relieved by a strange alliance of Roundhead troops under George Monck and the Irish Catholic general Owen Roe O'Neill. These temporary allies were soon fighting each other again however, after the landing in Ireland of the New Model Army in 1649. The war in Ulster was finally brought to an end when the Parliamentarians crushed the Irish Catholic Ulster army at the Battle of Scarrifholis, near Letterkenny in nearby County Donegal, in 1650.

During the Glorious Revolution, only Derry and nearby Enniskillen had a Protestant garrison by November 1688. An army of around 1,200 men, mostly "Redshanks" (Highlanders), under Alexander Macdonnell, 3rd Earl of Antrim, was slowly organised (they set out on the week William of Orange landed in England). When they arrived on 7 December 1688 the gates were closed against them and the Siege of Derry began. In April 1689, King James came to the city and summoned it to surrender. The King was rebuffed and the siege lasted until the end of July with the arrival of a relief ship.

18th and 19th centuries

The city was rebuilt in the 18th century with many of its fine Georgian style houses still surviving. The city's first bridge across the River Foyle was built in 1790. During the 18th and 19th centuries the port became an important embarkation point for Irish emigrants setting out for North America.

Also during the 19th century, it became a destination for migrants fleeing areas more severely affected by the Irish Potato Famine.[53][54] One of the most notable shipping lines was the McCorkell Line operated by Wm. McCorkell & Co. Ltd. from 1778.[55] The McCorkell's most famous ship was the Minnehaha, which was known as the "Green Yacht from Derry".[55]

Early 20th century

World War I

During World War I the city contributed over 5,000 men to the British Army from Catholic and Protestant families.

Partition

During the Irish War of Independence, the area was rocked by sectarian violence, partly prompted by the guerilla war raging between the Irish Republican Army and British forces, but also influenced by economic and social pressures. By mid-1920 there was severe sectarian rioting in the city.[57][58] Many lives were lost and in addition many Catholics and Protestants were expelled from their homes during this communal unrest. After a week's violence, a truce was negotiated by local politicians on both unionist and republican sides.

In 1921, following the Anglo-Irish Treaty and the Partition of Ireland, it unexpectedly became a 'border city', separated from much of its traditional economic hinterland in County Donegal.

World War II

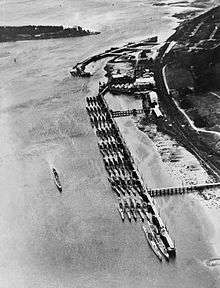

During World War II, the city played an important part in the Battle of the Atlantic.[59] Ships from the Royal Navy, the Royal Canadian Navy, and other Allied navies were stationed in the city and the United States military established a base. Over 20,000 Royal Navy, 10,000 Royal Canadian Navy, and 6,000 United States Navy personnel were stationed in the city during the war.[60] The establishment of the American presence in the city was the result of a secret agreement between the Americans and the British before the Americans entered the war.[61][62] It was the first American naval base in Europe and the terminal for American convoys en route to Europe.

The reason for such a high degree of military and naval activity was self-evident: Derry was the United Kingdom's westernmost port; indeed, the city was the westernmost Allied port in Europe: thus, Derry was a crucial jumping-off point, together with Glasgow and Liverpool, for the shipping convoys that ran between Europe and North America. The large numbers of military personnel in Derry substantially altered the character of the city, bringing in some outside colour to the local area, as well as some cosmopolitan and economic buoyancy during these years. Several airfields were built in the outlying regions of the city at this time, Maydown, Eglinton and Ballykelly. RAF Eglinton went on to become City of Derry Airport.

The city contributed significant number of men to the war effort throughout the services, most notably the 500 men in the 9th (Londonderry) Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment, known as the 'Derry Boys'. This regiment served in North Africa, the Sudan, Italy and mainland UK. Many others served in the Merchant Navy taking part in the convoys that supplied the UK and Russia during the war.

The border location of the city, and influx of trade from the military convoys allowed for significant smuggling operations to develop in the city.

At the conclusion of the Second World War, eventually some 60 U-boats of the German Kriegsmarine ended in the city's harbour at Lisahally after their surrender.[63] The initial surrender was attended by Admiral Sir Max Horton, Commander-in-Chief of the Western Approaches, and Sir Basil Brooke, third Prime Minister of Northern Ireland.[61]

Late 20th century

1950s and 1960s

The city languished after the second world war, with unemployment and development stagnating. A large campaign, led by the University for Derry Committee, to have Northern Ireland's second university located in the city, ended in failure.

The Civil Rights Movement

Derry was a focal point for the nascent civil rights movement in Northern Ireland.

Catholics were discriminated against under Unionist government in Northern Ireland, both politically and economically.[64][65][66][67] In the late 1960s the city became the flashpoint of disputes about institutional gerrymandering. Political scientist John Whyte explains that:

All the accusations of gerrymandering, practically all the complaints about housing and regional policy, and a disproportionate amount of the charges about public and private employment come from this area. The area – which consisted of Counties Tyrone and Fermanagh, Londonderry County Borough, and portions of Counties Londonderry and Armagh – had less than a quarter of the total population of Northern Ireland yet generated not far short of three-quarters of the complaints of discrimination...The unionist government must bear its share of responsibility. It put through the original gerrymander which underpinned so many of the subsequent malpractices, and then, despite repeated protests, did nothing to stop those malpractices continuing. The most serious charge against the Northern Ireland government is not that it was directly responsible for widespread discrimination, but that it allowed discrimination on such a scale over a substantial segment of Northern Ireland.[68]

A civil rights demonstration in 1968 led by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association was banned by the Government and blocked using force by the Royal Ulster Constabulary.[67] The events that followed the August 1969 Apprentice Boys parade resulted in the Battle of the Bogside, when Catholic rioters fought the police, leading to widespread civil disorder in Northern Ireland and is often dated as the starting point of the Troubles.

On Sunday 30 January 1972, 13 unarmed civilians were shot dead by British paratroopers during a civil rights march in the Bogside area. Another 13 were wounded and one further man later died of his wounds. This event came to be known as Bloody Sunday.

The Troubles

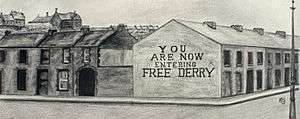

The conflict which became known as the Troubles is widely regarded as having started in Derry with the Battle of the Bogside. The Civil Rights Movement had also been very active in the city. In the early 1970s the city was heavily militarised and there was widespread civil unrest. Several districts in the city constructed barricades to control access and prevent the forces of the state from entering.

Violence eased towards the end of the Troubles in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Irish journalist Ed Maloney claims in The Secret History of the IRA that republican leaders there negotiated a de facto ceasefire in the city as early as 1991. Whether this is true or not, the city did see less bloodshed by this time than Belfast or other localities.

The city was visited by a killer whale in November 1977 at the height of the Troubles; it was dubbed Dopey Dick by the thousands who came from miles around to see him.[69]

Governance

From 1613 the city was governed by the Londonderry Corporation. In 1898 this became Londonderry County Borough Council, until 1969 when administration passed to the unelected Londonderry Development Commission. In 1973 a new district council with boundaries extending to the rural south-west was established under the name Londonderry City Council, renamed in 1984 to Derry City Council, consisting of five electoral areas: Cityside, Northland, Rural, Shantallow and Waterside. The council of 30 members was re-elected every four years. As of the 2011 election, 14 Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) members, ten Sinn Féin, five Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), and one Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) made up the council. The mayor and deputy mayor were elected annually by councillors. The local authority boundaries corresponded to the Foyle constituency of the Parliament of the United Kingdom and the Foyle constituency of the Northern Ireland Assembly. In European Parliament elections, it was part of the Northern Ireland constituency.

The council merged with Strabane District Council in April 2015 under local government reorganisation to become Derry and Strabane District Council.

The councillors elected in 2014 for the city are:

| Name | Party | |

|---|---|---|

| Sandra Duffy | Sinn Féin | |

| Tony Hassan | Sinn Féin | |

| Elisha McCallion | Sinn Féin | |

| Mickey Cooper | Sinn Féin | |

| Eric McGinley | Sinn Féin | |

| Kevin Campbell | Sinn Féin | |

| Patricia Logue | Sinn Féin | |

| Colly Kelly | Sinn Féin | |

| Christopher Jackson | Sinn Féin | |

| Angela Dobbins | SDLP | |

| Brian Tierney | SDLP | |

| John Boyle | SDLP | |

| Shauna Cusack | SDLP | |

| Seán Carr | SDLP | |

| Gerard Diver | SDLP | |

| Martin Reilly | SDLP | |

| Dermot Quigley | Independent | |

| Darren O'Reilly | Independent | |

| Gary Donnelly | Independent | |

| Hilary McClintock | DUP | |

| Drew Thompson | DUP | |

| David Ramsey | DUP | |

| Mary Hamilton | UUP | |

Coat of arms and motto

The devices on the city's arms are a skeleton and a three-towered castle on a black field, with the "chief" or top third of the shield showing the arms of the City of London: a red cross and sword on white. In the centre of the cross is a gold harp.[70][71] In unofficial use the harp sometimes appears above the arms as a crest.[72]

The arms were confirmed by Daniel Molyneux, the Ulster King of Arms, in 1613, following the town's incorporation.[72] Molyneux's notes state that the original arms of Derry were "the picture of death (or a skeleton) sitting on a mossie ston and in the dexter point a castle". To this design he added, at the request of the new mayor, "a chief, the armes of London". Molyneux goes on to state that the skeleton is symbolic of Derry's ruin at the hands of the Irish rebel Cahir O'Doherty, and that the silver castle represents its renewal through the efforts of the London guilds: "[Derry] hath since bene (as it were) raysed from the dead by the worthy undertakinge of the Ho'ble Cittie of London, in memorie whereof it is hence forth called and knowen by the name of London Derrie."[72]

Local legend offers different theories as to the origin of the skeleton. One identifies it as Walter de Burgh, who was starved to death in the Earl of Ulster's dungeons in 1332.[73] Another identifies it as Cahir O'Doherty himself, who was killed in a skirmish near Kilmacrennan in 1608 (but was popularly believed to have wasted away while sequestered in his castle at Buncrana).[72] In the days of gerrymandering and anti-Catholic discrimination, Derry's Catholics often claimed in dark wit that the skeleton was a Catholic waiting for a job and a council house.[46] However, a report commissioned by the city council in 1979 established that there was no basis for any of the popular theories, and that the skeleton "[is] purely symbolic and does not refer to any identifiable person".[74]

The 1613 arms depicted a harp in the centre of the cross, but this was omitted from later depictions of the city arms, and in the 1952 letters patent confirming the arms to the Londonderry Corporation.[75] In 2002 Derry City Council applied to the College of Arms to have the harp restored, and Garter and Norroy & Ulster Kings of Arms issued letters patent to that effect in 2003, having accepted the 17th century evidence.[71]

The motto attached to the coat of arms reads in Latin, "Vita, Veritas, Victoria". This translates into English as "Life, Truth, Victory".[46]

Geography

Derry is characterised by its distinctively hilly topography.[76] The River Foyle forms a deep valley as it flows through the city, making Derry a place of very steep streets and sudden, startling views. The original walled city of Londonderry lies on a hill on the west bank of the River Foyle. In the past, the river branched and enclosed this wooded hill as an island; over the centuries, however, the western branch of the river dried up and became a low-lying and boggy district that is now called the Bogside.[77]

Today, modern Derry extends considerably north and west of the city walls and east of the river. The half of the city the west of the Foyle is known as the Cityside and the area east is called the Waterside. The Cityside and Waterside are connected by the Craigavon Bridge and Foyle Bridge, and by a foot bridge in the centre of the city called Peace Bridge. The district also extends into rural areas to the southeast of the city.

This much larger city, however, remains characterised by the often extremely steep hills that form much of its terrain on both sides of the river. A notable exception to this lies on the north-eastern edge of the city, on the shores of Lough Foyle, where large expanses of sea and mudflats were reclaimed in the middle of the 19th century. Today, these sloblands are protected from the sea by miles of sea walls and dikes. The area is an internationally important bird sanctuary, ranked among the top 30 wetland sites in the UK.[78]

Other important nature reserves lie at Ness Country Park,[79] 10 miles (16 km) east of Derry; and at Prehen Wood,[80] within the city's south-eastern suburbs.

Climate

Derry has, like most of Ireland, a temperate maritime climate[81] according to the Köppen climate classification system. The nearest official Met Office Weather Station for which climate data is available is Carmoney,[82] just west of City of Derry Airport and about 5 miles (8 km) north east of the city centre. However, observations ceased in 2004 and the nearest Weather Station is currently Ballykelly, due 12 miles (19 km) east north east.[83] Typically, 27 nights of the year will report an air frost at Ballykelly, and at least 1 mm of precipitation will be reported on 170 days (1981–2010 averages).

The lowest temperature recorded at Carmoney was −11.0 °C (12.2 °F) on 27 December 1995.[84]

| Climate data for Ballykelly SAMOS (Derry Airport 1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.0 (46.4) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.1 (50.2) |

12.1 (53.8) |

15 (59) |

17.0 (62.6) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.5 (65.3) |

16.7 (62.1) |

13.5 (56.3) |

10.2 (50.4) |

8 (46) |

13.0 (55.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.2 (36.0) |

2.1 (35.8) |

3.5 (38.3) |

4.8 (40.6) |

7 (45) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.6 (52.9) |

11.4 (52.5) |

9.8 (49.6) |

7.2 (45.0) |

4.5 (40.1) |

2.5 (36.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 83.5 (3.29) |

62.7 (2.47) |

69.8 (2.75) |

55.2 (2.17) |

51.2 (2.02) |

56.1 (2.21) |

66.1 (2.60) |

75.3 (2.96) |

68.7 (2.70) |

89.0 (3.50) |

86.7 (3.41) |

88.4 (3.48) |

852.6 (33.57) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 17 | 13 | 16 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 16 | 19 | 15 | 170 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 52.3 | 72.4 | 100.9 | 155.0 | 202.7 | 161.4 | 140.4 | 141.1 | 119.6 | 102.5 | 57.9 | 37.7 | 1,343.9 |

| Source: MetOffice[85] | |||||||||||||

Demography

Derry Urban Area (DUA), including the city and the neighbouring settlements of Culmore, Newbuildings and Strathfoyle, is classified as a city by the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) since its population exceeds 75,000. On census day (27 March 2011) there were 105,066 people living in Derry Urban Area. Of these, 27% were aged under 16 years and 14% were aged 60 and over; 49% of the population were male and 51% were female; 75% were from a Roman Catholic background and 23% (up three per cent from 2001) were from a Protestant background.[86]

The mid-2006 population estimate for the wider Derry City Council area was 107,300.[87] Population growth in 2005/06 was driven by natural change, with net out-migration of approximately 100 people.[87]

The city was one of the few in Ireland to experience an increase in population during the Irish Potato Famine as migrants came to it from other, more heavily affected areas.[53]

Protestant minority

Concerns have been raised by both communities over the increasingly divided nature of the city. There were about 17,000 Protestants on the west bank of the River Foyle in 1971.[88] The proportion rapidly declined during the 1970s;[89] the 2011 census recorded 3,169 Protestants on the west bank, compared to 54,976 Catholics,[90] and it is feared that the city could become permanently divided.[91][92]

However, concerted efforts have been made by local community, church and political leaders from both traditions to redress the problem. A conference to bring together key actors and promote tolerance was held in October 2006.[93] Ken Good, the Church of Ireland Bishop of Derry and Raphoe, said he was happy living on the cityside. "I feel part of it. It is my city and I want to encourage other Protestants to feel exactly the same", he said.[93]

Support for Protestants in the district has been strong from the former SDLP city Mayor Helen Quigley. She has made inclusion and tolerance key themes of her mayoralty. Quigley said it is time for "everyone to take a stand to stop the scourge of sectarian and other assaults in the city."[94]

Economy

History

The economy of the district was based significantly on the textile industry until relatively recently. For many years women were commonly the sole wage earners working in the shirt factories while the men in comparison had high levels of unemployment.[95] This led to significant male emigration.[96] The history of shirt making in the city dates to 1831, said to have been started by William Scott and his family who first exported shirts to Glasgow.[97] Within 50 years, shirt making in the city was the most prolific in the UK with garments being exported all over the world. It was known so well that the industry received a mention in Das Kapital by Karl Marx, when discussing the factory system:

The shirt factory of Messrs. Tille at Londonderry, which employs 1,000 operatives in the factory itself, and 9,000 people spread up and down the country and working in their own houses.[98]

The industry reached its peak in the 1920s employing around 18,000 people.[46] In modern times however the textile industry declined due largely to lower Asian wages.[99]

A long-term foreign employer in the area is Du Pont, which has been based at Maydown since 1958, its first European production facility.[100] Originally Neoprene was manufactured at Maydown and subsequently followed by Hypalon. More recently Lycra and Kevlar production units were active.[101] Thanks to a healthy worldwide demand for Kevlar which is made at the plant, the facility recently undertook a £40 million upgrade to expand its global Kevlar production. Du Pont has stated that contributing factors to its continued commitment to Maydown are "low labour costs, excellent communications, and tariff-free, easy access to the Britain and European continent."

Inward investment

In the last 15 years there has been a drive to increase inward investment in the city, more recently concentrating on digital industries. Currently the three largest private-sector employers are American firms.[102] Economic successes have included call centres and a large investment by Seagate, which has operated a factory in the Springtown Industrial Estate since 1993. Seagate currently employs over 1,000 people, producing more than half of the company's total requirement for hard drive read-write heads.

A controversial new employer in the area was Raytheon Systems Limited, a software division of the American defence contractor, which was set up in Derry in 1999.[103] Although some of the local people welcomed the jobs boost, others in the area objected to the jobs being provided by a firm involved heavily in the arms trade.[104] Following four years of protest by the Foyle Ethical Investment Campaign, in 2004 Derry City Council passed a motion declaring the district a "A 'No – Go' Area for the Arms Trade",[105] and in 2006 its offices were briefly occupied by anti-war protestors who became known as the Raytheon 9.[106] In 2009, the company announced that it was not renewing its lease when it expired in 2010 and was looking for a new location for its operations.[107]

Other significant multinational employers in the region include Firstsource of India, INVISTA, Stream International, Perfecseal, NTL, Northbrook Technology of the United States, Arntz Belting and Invision Software of Germany, and Homeloan Management of the UK. Major local business employers include Desmonds, Northern Ireland's largest privately owned company, manufacturing and sourcing garments, E&I Engineering, St. Brendan's Irish Cream Liqueur and McCambridge Duffy, one of the largest insolvency practices in the UK.[108]

Even though the city provides cheap labour by standards in Western Europe, critics have noted that the grants offered by the Northern Ireland Industrial Development Board have helped land jobs for the area that only last as long as the funding lasts.[109] This was reflected in questions to the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Richard Needham, in 1990.[110] It was noted that it cost £30,000 to create one job in an American firm in Northern Ireland.

Critics of investment decisions affecting the district often point to the decision to build a new university building in nearby (predominantly Protestant) Coleraine rather than developing the Ulster University Magee Campus. Another major government decision affecting the city was the decision to create the new town of Craigavon outside Belfast, which again was detrimental to the development of the city. Even in October 2005, there was perceived bias against the comparatively impoverished North West of the province, with a major civil service job contract going to Belfast. Mark Durkan, the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) leader and Member of Parliament (MP) for Foyle was quoted in the Belfast Telegraph as saying:

The fact is there has been consistent under-investment in the North West and a reluctance on the part of the Civil Service to see or support anything west of the Bann, except when it comes to rate increases, then they treat us equally.

In July 2005, the Irish Minister for Finance, Brian Cowen, called for a joint task force to drive economic growth in the cross border region. This would have implications for Counties Londonderry, Tyrone, and Donegal across the border.

Shopping

The city is the north west's foremost shopping district, housing two large shopping centres along with numerous shop packed streets serving much of the greater county, as well as Tyrone and Donegal.

The city centre has two main shopping centres; the Foyleside Shopping Centre which has 45 stores and 1,430 parking spaces, and the Richmond Centre, which has 39 retail units. The Quayside Shopping Centre also serves the city-side and there is also Lisnagelvin Shopping Centre in the Waterside. These centres, as well as local-run businesses, feature numerous national and international stores. A recent addition was the Crescent Link Retail Park located in the Waterside with many international chain stores, including Homebase, Currys & PC World (stores combined), Carpet Right, Argos Extra, Toys R Us, Halfords, DW Sports (formerly JJB Sports), Pets at Home, Next Home, Starbucks, McDonald's, Tesco Express and M&S Simply Food. In the short period of time that this site has been operational, it has quickly grown to become the second largest retail park in Northern Ireland (second only to Sprucefield in Lisburn).[111] Plans have also been approved for Derry's first Asda store, which will be located at the retail park sharing a unit with Homebase.[112] Sainsbury's also applied for planning permission for a store at Crescent Link, but Environment Minister Alex Attwood turned it down.[113]

Until the store's closure in March 2016, the city was also home to the world's oldest independent department store, Austins. Established in 1830, Austins predates Jenners of Edinburgh by 5 years, Harrods of London by 15 years and Macy's of New York by 25 years.[114] The store's five-story Edwardian building is located within the walled city in the area known as The Diamond.

Landmarks

Derry is renowned for its architecture. This can be primarily ascribed to the formal planning of the historic walled city of Derry at the core of the modern city. This is centred on the Diamond with a collection of late Georgian, Victorian and Edwardian buildings maintaining the gridlines of the main thoroughfares (Shipquay Street, Ferryquay Street, Butcher Street and Bishop Street) to the City Gates. St Columb's Cathedral does not follow the grid pattern reinforcing its civic status. This Church of Ireland Cathedral was the first post-Reformation Cathedral built for an Anglican church. The construction of the Roman Catholic St Eugene's Cathedral in the Bogside in the 19th-century was another major architectural addition to the city. The Townscape Heritage Initiative has funded restoration works to key listed buildings and other older structures.

In the three centuries since their construction, the city walls have been adapted to meet the needs of a changing city. The best example of this adaptation is the insertion of three additional gates – Castle Gate, New Gate and Magazine Gate – into the walls in the course of the 19th century. Today, the fortifications form a continuous promenade around the city centre, complete with cannon, avenues of mature trees and views across Derry. Historic buildings within the city walls include St Augustine's Church, which sits on the city walls close to the site of the original monastic settlement; the copper-domed Austin's department store, which claims to the oldest such store in the world; and the imposing Greek Revival Courthouse on Bishop Street. The red-brick late-Victorian Guildhall, also crowned by a copper dome, stands just beyond Shipquay Gate and close to the river front.

There are many museums and sites of interest in and around the city, including the Foyle Valley Railway Centre, the Amelia Earhart Centre And Wildlife Sanctuary, the Apprentice Boys Memorial Hall, Ballyoan Cemetery, The Bogside, numerous murals by the Bogside Artists, Derry Craft Village, Free Derry Corner, O'Doherty Tower (now home to part of the Tower Museum), the Harbour Museum, the Museum of Free Derry, Chapter House Museum, the Workhouse Museum, the Nerve Centre, St. Columb's Park and Leisure Centre, Creggan Country Park, The Millennium Forum and the Foyle and Craigavon bridges.

Attractions include museums, a vibrant shopping centre and trips to the Giant's Causeway, which is approximately 50 miles (80 km) away, though poorly connected by public transport. Lonely Planet called Derry the fourth best city in the world to see in 2013.[115]

On 25 June 2011, the Peace Bridge opened. It is a cycle and foot bridge that begins from the Guild Hall in the city centre of Derry City to Ebrington Square and St Columb's Park on the far side of the River Foyle. It symbolizes the unity of the Protestant community and the Nationalist community who are settled on either sides of the Foyle River. "The Derry Peace Bridge has become an integral part of Derry City’s infrastructure and has changed the way local people use and view their city with over 3 million people having crossed it so far and many of the locals using it daily."[116]

Future projects include the Walled City Signature Project, which intends to ensure that the city's walls become a world class tourist experience.[117] The Ilex Urban Regeneration Company is charged with delivering several landmark redevelopments. It has taken control of two former British Army barracks in the centre of the city. The Ebrington site is nearing completion and is linked to the city centre by the new Peace Bridge.

Transport

The transport network is built out of a complex array of old and modern roads and railways throughout the city and county. The city's road network also makes use of two bridges to cross the River Foyle, the Craigavon Bridge and the Foyle Bridge, the longest bridge in Ireland. Derry also serves as a major transport hub for travel throughout nearby County Donegal.

In spite of it being the second city of Northern Ireland (and it being the second-largest city in all of Ulster), road and rail links to other cities are below par for its standing. Many business leaders claim that government investment in the city and infrastructure has been badly lacking. Some have stated that this is due to its outlying border location whilst others have cited a sectarian bias against the region west of the River Bann due to its high proportion of Catholics.[118][119] There is no direct motorway link with Dublin or Belfast. The rail link to Belfast has been downgraded over the years so that, presently, it is not a viable alternative to the roads for industry to rely on. There are currently plans for £1 billion worth of transport infrastructure investment in and around the district.[120] Planned upgrades to the A5 Dublin road agreed as part of the Good Friday Agreement and St. Andrews Talks fell through when the government of the Republic of Ireland reneged on its funding citing the recent economic crisis.[121]

Buses

Most public transport in Northern Ireland is operated by the subsidiaries of Translink. Originally the city's internal bus network was run by Ulsterbus, which still provides the city's connections with other towns in Northern Ireland. The city's buses are now run by Ulsterbus Foyle,[122] just as Translink Metro now provides the bus service in Belfast. The Ulsterbus Foyle network offers 13 routes across the city into the suburban areas, excluding an Easibus link which connects to the Waterside and Drumahoe,[123] and a free Rail Link Bus runs from the Waterside Railway Station to the city centre. All buses leave from the Foyle Street Bus Station in the city centre.

Long-distance buses depart from Foyle Street Bus Station to destinations throughout Ireland. Buses are operated by both Ulsterbus and Bus Éireann on cross-border routes. Lough Swilly formerly operated buses to Co. Donegal, but the company entered liquidation and is no longer in operation. There is a half-hourly service to Belfast every day, called the Maiden City Flyer, which is the Goldline Express flagship route. There are hourly services to Strabane, Omagh, Coleraine, Letterkenny and Buncrana, and up to twelve services a day to bring people to Dublin. There is a daily service to Sligo, Galway, Shannon Airport and Limerick.

Air

City of Derry Airport, the council-owned airport near Eglinton, has been growing in recent years with new investment in extending the runway and plans to redevelop the terminal.[124] It is hoped that the new investment will add to the airport's currently limited array of domestic and international flights and reduce the annual subsidy of £3.5 million from the local council.

The A2 from Maydown to Eglinton, serving airport, has recently been turned into a dual carriageway.[125] City of Derry airport is the main regional airport for County Donegal, County Londonderry and west County Tyrone as well as Derry City itself.

The airport is served by Loganair and Ryanair with scheduled flights to Glasgow Airport, Edinburgh Airport, Manchester Airport, Liverpool John Lennon Airport[126] and London Stansted all year round with a summer schedule to Mallorca with TUI Airways

Railways

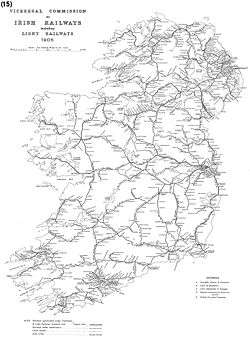

The city is served by a single rail link that is subsidized, alongside much of Northern Ireland's railways, by Northern Ireland Railways (N.I.R.). The link primarily provides passenger services from the city to Belfast, via several stops that include Coleraine, Ballymoney, and Antrim, and connections to links with other parts of Northern Ireland. The route itself is the only remaining rail link used by trains; most of the lines developed in the mid 19th century fell into decline towards the mid 20th century from competition by new road networks. The original rail network that served the city included four different railways that, between them, linked the city with much of the province of Ulster, plus a harbour railway network that linked the other four lines, and a tramway on the City side of the Foyle. Usage of the rail link between Derry and Belfast remains questionable for commuters, due to the journey time of over two hours making it slower centre-to-centre than the 100-minute Ulsterbus Goldline Express service.[127]

Railway history

19th century - early 20th century growth

Several railways began operation around the city of Derry within the middle of the 19th century. The companies that set up links helped to provide key links for the city towards other towns and cities across Ireland, for the transportation of passengers and freight. The lines that were constructed featured a mixture of Irish gauge and narrow gauge railways, and companies that operated them included:

- The Londonderry and Enniskillen Railway (L&ER) - The rail company constructed Derry's first railway in 1845 with Irish gauge (5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm)) track. The line operated from a temporary station at Cow Market on the City side of the Foyle, reaching Strabane in 1847,[128] before being extended from Cow Market to its permanent terminus at Foyle Road in 1850.[129] The L&ER reached Omagh in 1852 and Enniskillen in 1854,[129] and was absorbed into the Great Northern Railway (Ireland) in 1883.[130]

- The Londonderry and Coleraine Railway (L&CR) - The rail company constructed an Irish gauge line to the city in 1852, opening a terminus at Waterside.[129] The Belfast and Northern Counties Railway leased the line from 1861, before taking it over in 1871.

- The Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway (L&LSR) - The rail company opened a line between Farland Point on Lough Swilly and a temporary terminus at Pennyburn in 1863,[129] before extending the line in 1866 to a more permanent terminus at Graving Dock.[129] The L&LSR was conceived to operate on Irish gauge track when it was constructed, but was converted in 1885 to 3 ft (914 mm) narrow gauge to link it with the Letterkenny Railway.

- The Londonderry Port and Harbour Commissioners (LPHC) - The rail company established a line that linked Graving Dock and Foyle Road stations through Middle Quay in 1867, before extending the line to create a rail connection with Waterside station, via the newly constructed Carlisle Bridge, in 1868.[129] When the bridge was replaced in 1933 with the double-deck Craigavon Bridge, the LPHC was assigned to operating on the lower deck.

In 1900, the 3 ft (914 mm) gauge Donegal Railway was extended to the city from Strabane, with construction establishing the Londonderry Victoria Road railway terminus and creating a junction with the LPHC railway.[129] The LPHC line was altered to dual gauge which allowed 3 ft (914 mm) gauge traffic between the Donegal Railway and L&LSR as well as Irish gauge traffic between the GNR and B&NCR. By 1905, the government of the United Kingdom offered subsidies to both the L&LSR and the Donegal Railway to build extensions to their railway networks into remote parts of County Donegal, which soon developed Derry (alongside Strabane) into becoming a key rail hub by 1905 for the county and surrounding regions.[131] In 1906 the Northern Counties Committee (NCC, successor to the B&NCR) and the GNR jointly took over the Donegal Railway, making it the County Donegal Railways Joint Committee (CDRJC).

Alongside the railways, the city was severed by a standard gauge (1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in)) tramway, the City of Derry Tramways.[132] The tramway was opened in 1897 and consisted of horse trams that operated along a single line, 1.5 miles (2.4 km) long, which ran along the City side of the Foyle parallel to the LPHC's line on that side of the river.[133] The line never converted to electrically operated trams,[132] and was closed in 1919.[132]

20th century decline

In 1922, the partition of Ireland dramatically caused disruptions to the city's rail links, except for the NNC route to Coleraine.[128] The creation of an international frontier with County Donegal changed trade patterns to the detriment of the railways affected by the partition, placing border posts on every line to and from Derry, causing great delays to trains and disrupting timekeeping from custom inspections - the L&LSR faced inspections between Pennyburn and Bridge End; the CDRJC faced inspections beyond Strabane; and the GNR line faced inspections between Derry and Strabane.[128] Custom agreements negotiated over the next few years between Britain and Ireland enabled GNR trains to travel to and from Derry - such trains would be allowed to pass without inspection through the Free State, unless they served local stations on the west bank of the Foyle - while goods transported by all railways between different parts of the Free State would be allowed to pass through Northern Ireland under customs bond. Despite these agreements, local passenger and goods traffic continued to be delayed by customs examinations.

The decline of most of Derry's rail links took place after the Second World War, due to increasing competition by road links. The L&LSR closed its line in 1953, followed by the CDRJC in 1954.[134] The Ulster Transport Authority, who took over the NCC in 1949 and the GNR's lines in Northern Ireland in 1958, took control of the LPHC railway before closing it in 1962,[135] before eventually shutting down the former GNR line to Derry in 1965, after the submission of The Benson Report to the Northern Ireland Government two years prior to the closure.[134][135][136] This left the former L&CR line to Coleraine as the sole railway link for the city, providing a passenger service to Belfast, alongside CIÉ freight services to Donegal. By the 1990s, the service began to deteriorate.

21st century regeneration

In 2008, the Department for Regional Development announced plans to relay the track between Derry and Coleraine - the plan, aimed at being completed by 2013, included adding a passing loop to increase traffic capacity, and increasing the number of trains with two additional diesel multiple units.[137] Additional phases of the plan also included improvements to existing stations along the line, and the restoration of the former Victoria Road terminus building to prepare for the relocation of the city's current terminus station to the site, all for completion by late 2019. Costing around £86 million, the improvements were aimed at reducing the journey time to Belfast by 30 minutes and allowing commuter trains to arrive before 9 a.m. for the first time.[137]

Road network

The largest road investment in the north west's history is now (2010) taking place with building of the 'A2 Broadbridge Maydown to City of Derry Airport dualling' project[138] and announcement of the 'A6 Londonderry to Dungiven Dualling Scheme'[139] which will help to reduce the travel time to Belfast.[140] The latter project brings a dual-carriageway link between Northern Ireland's two largest cities one step closer. The project is costing £320 million and is expected to be completed in 2016.

In October 2006 the Government of Ireland announced that it was to invest €1 billion in Northern Ireland;[141] and one of the planned projects will be 'The A5 Western Transport Corridor',[142] the complete upgrade of the A5 Derry – Omagh – Aughnacloy (– Dublin) road, around 90 kilometres (56 miles) long, to dual carriageway standard.[143]

It is not yet known if these two separate projects will connect at any point, although there have been calls for some form of connection between the two routes. In June 2008 Conor Murphy, Minister for Regional Development, announced that there will be a study into the feasibility of connecting the A5 and A6.[120] Should it proceed, the scheme would most likely run from Drumahoe to south of Prehen along the south east of the city.[137]

Sea

Londonderry Port at Lisahally is the United Kingdom's most westerly port and has capacity for 30,000-ton vessels. The Londonderry Port and Harbour Commissioners (LPHC) announced record turnover, record profits and record tonnage figures for the year ended March 2008. The figures are the result of a significant capital expenditure programme for the period 2000 to 2007 of about £22 million. Tonnage handled by LPHC increased almost 65% between 2000 and 2007, according to the latest annual results.

The port gave vital Allied service in the longest running campaign of the Second World War, the Battle of the Atlantic, and saw the surrender of the German U-boat fleet at Lisahally on 8 May 1945.[144]

Inland waterways

The tidal River Foyle is navigable from the coast at Derry to approximately 10 miles (16 km) inland. In 1796, the Strabane Canal was opened, continuing the navigation a further 4 miles (6 km) southwards to Strabane. The canal was closed in 1962.

Education

Derry is home to the Magee Campus of Ulster University, formerly Magee College. However, Lockwood's[145] 1960s decision to locate Northern Ireland's second university in Coleraine rather than Derry helped contribute to the formation of the civil rights movement that ultimately led to The Troubles. Derry was the town more closely associated with higher learning, with Magee College already more than a century old by that time.[146][147] In the mid-1980s a half-hearted attempt was made at rectifying this mistake by forming Magee College as a campus of the Ulster University but this has failed to stifle calls for the establishment of an independent University in Derry that can grow to it full potential.[148] The campus has never thrived and currently only has 3,500 students out of a total Ulster University student population of 27,000. Ironically, although Coleraine is blamed by many in the city for 'stealing the University', it has only 5,000 students, the remaining 19,000 being based in Belfast.[149]

The North West Regional College is also based in the city. In recent years it has grown to almost 30,000 students.[150]

One of the two oldest secondary schools in Northern Ireland is located in Derry, Foyle and Londonderry College. It was founded in 1616 by the merchant taylors and remains a popular choice. Other secondary schools include St. Columb's College, Oakgrove Integrated College, St Cecilia's College, St Mary's College, St. Joseph's Boys' School, Lisneal College, Thornhill College, Lumen Christi College and St. Brigid's College. There are also numerous primary schools.

Sports

The city is home to sports clubs and teams. Both association football and Gaelic football are popular in the area.

Association football

In association football, the city's most prominent clubs include Derry City who play in the national league of the Republic of Ireland; Institute of the NIFL Premiership as well as Maiden City and Trojans, both of the Northern Ireland Intermediate League. In addition to these clubs, who all play in national leagues, other clubs are based in the city. The local football league governed by the IFA is the North-West Junior League, which contains many clubs from the city, such as BBOB (Boys Brigade Old Boys) and Lincoln Courts. The city's other junior league is the Derry and District League and teams from the city and surrounding areas participate, including Don Boscos and Creggan Swifts. The Foyle Cup youth soccer tournament is held annually in the city. It has attracted many notable teams in the past, including Werder Bremen, IFK Göteborg and Ferencváros.

Gaelic football

In Gaelic football Derry GAA are the county team and play in the Gaelic Athletic Association's National Football League, Ulster Senior Football Championship and All-Ireland Senior Football Championship. They also field hurling teams in the equivalent tournaments. There are many Gaelic games clubs in and around the city, for example Na Magha CLG, Steelstown GAC, Doire Colmcille CLG, Seán Dolans GAC, Na Piarsaigh CLG Doire Trasna and Slaughtmanus GAC.

Boxing

There are many boxing clubs, the most well-known being The Ring Boxing Club, which is based on the City side, and associated with Charlie Nash[151] and John Duddy,[152] amongst others.

A recent development has seen the formation of Rochester's Amateur Boxing club, bringing boxing to the residents of the city's Waterside.

Rugby union

Rugby union is also quite popular in the city, with the City of Derry Rugby Club situated not far from the city centre.[153] City of Derry won both the Ulster Towns Cup and the Ulster Junior Cup in 2009. Londonderry YMCA RFC is another rugby club and is based in the village of Drumahoe which is in the outskirts of the city.

Basketball

The city's only basketball club is North Star Basketball Club which has teams in the Basketball Northern Ireland senior and junior Leagues.[154]

Cricket

Cricket is also a popular sport in the city, particularly in the Waterside. The city is home to two cricket clubs, Brigade Cricket Club and Glendermott Cricket Club, both of whom play in the North West Senior League.

Golf

Golf is also a sport which is popular with many in the city. There are two golf clubs situated in the city, City of Derry Golf Club and Foyle International Golf Centre.

Culture

In recent years the city and surrounding countryside have become well known for their artistic legacy, producing Nobel Prize-winning poet Seamus Heaney,[155] poet Seamus Deane, playwright Brian Friel,[156] writer and music critic Nik Cohn, artist Willie Doherty, socio-political commentator and activist Eamonn McCann[157] and bands such as The Undertones. The large political gable-wall murals of Bogside Artists, Free Derry Corner, the Foyle Film Festival, the Derry Walls, St Eugene's and St Columb's Cathedrals and the annual Halloween street carnival[158] are popular tourist attractions. In 2010, Derry was named the UK's tenth 'most musical' city by PRS for Music.[159][159]

In May 2013 a perpetual Peace Flame Monument was unveiled by Martin Luther King III and Presbyterian minister Rev. David Latimer. The flame was lit by children from both traditions in the city and is one of only 15 such flames across the world.[160][161]

Media

The local papers the Derry Journal (known as the Londonderry Journal until 1880) and the Londonderry Sentinel reflect the divided history of the city: the Journal was founded in 1772 and is Ireland's second oldest newspaper;[46] the Sentinel newspaper was formed in 1829 when new owners of the Journal embraced Catholic Emancipation, and the editor left the paper to set up the Sentinel.

There are numerous radio stations receivable: the largest stations based in the city are BBC Radio Foyle[162] and the commercial station Q102.9.[163]

There was a locally based television station, C9TV, one of only two local or 'restricted' television services in Northern Ireland, which ceased broadcasts in 2007.

Night-life

The city's night-life is mainly focused on the weekends, with several bars and clubs providing "student nights" during the weekdays. Waterloo Street and Strand Road provide the main venues. Waterloo Street, a steep street lined with both Irish traditional and modern pubs, frequently has live rock and traditional music at night.

Events

- In 2013, Derry became the first city to be designated UK City of Culture, having been awarded the title in July 2010.[15][16]

- Also in 2013 the city hosted Radio 1's Big Weekend[164] and the Lumiere festival.[165]

- The "Banks of the Foyle Hallowe'en Carnival" (known in Irish as Féile na Samhna) in Derry are a huge tourism boost for the city. The carnival is promoted as being the first and longest running Halloween carnival in the whole of Ireland,[166][167] It is called the largest street party in Ireland by the Derry Visitor and Convention Bureau with more than 30,000 ghoulish revellers taking to the streets annually.[168]

- In March, the city hosts the Big Tickle Comedy Festival, which in 2006 featured Dara Ó Briain and Colin Murphy. In April the city plays host to the City of Derry Jazz and Big Band Festival and in November the Foyle Film Festival, the biggest film festival in Northern Ireland.

- The Siege of Derry is commemorated annually by the fraternal organisation the Apprentice Boys of Derry in the week-long Maiden City Festival.

- The Instinct Festival is an annual youth festival celebrating the Arts. It is held around Easter and has proven a success in recent years.

- Celtronic is a major annual electronic dance festival held at venues all around the city. The 2007 Festival featured the DJ, Erol Alkan.

- The Millennium Forum is the main theatre in the city, it holds numerous shows weekly.

- On 9 December 2007 Derry entered the Guinness Book of Records when 13,000 Santas gathered to break the world record, beating previous records held by Liverpool and Las Vegas.[169]

- Winner of the 2005 Britain in Bloom competition (City category). Runner-up 2009.

References in popular music

|

|

Notable people

Notable people who were born or have lived in Derry include:

- Frederick Hervey, Bishop of Derry and 4th Earl of Bristol

- William Thomas Gaul, became Bishop of Mashonaland

- Edward Leach, recipient of the Victoria Cross

- The Restoration dramatist George Farquhar

- Authors Joyce Cary, Seamus Deane, Jennifer Johnston and Nell McCafferty

- Poet and Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney

- Social Democratic and Labour Party founder and Nobel Peace Prize winner John Hume

- Scientist and Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine winner William C. Campbell[172][173]

- Deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland Martin McGuinness

- Republic of Ireland national football team head coach Martin O'Neill

- Everton player Darron Gibson

- Actresses Amanda Burton and Roma Downey

- Girls Aloud member Nadine Coyle

- Neil Hannon lead singer of The Divine Comedy

- Eurovision Song Contest winner and former politician Dana

- The band The Undertones and their one-time lead singer Feargal Sharkey

- Jimmy McShane of Baltimora

- Clare Crockett, a catholic nun

- Triathlete Aileen Morrison

- Tom McGuinness, Gaelic footballer[174]

- Damian McGinty and Keith Harkin, vocalists with the group Celtic Thunder

- John Park, recipient of the Victoria Cross

- Daniel Quigley (World ISKA Professional Super Heaveyweight Kickboxing Champion)[175]

- Miles Ryan, recipient of the Victoria Cross

- Professional darts player Daryl Gurney

See also

- Ballynagalliagh

- Derry Girls

- List of abbeys and priories in County Londonderry

- List of towns and villages in Northern Ireland

- Scouting in Northern Ireland

References

- Smyth, Anne. "Tha Yeir o Grace". Ullans (Nummer 11 Ware 2010). Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- An Acoont o tha Darg up tae 31 Decemmer 2000 (PDF). Tha Boord o Leid. 2000. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- Smith, Dr Clifford. "Ulster's Hiddlin Swaatch". Culture Northern Ireland. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- "PostTowns by UK Postcode Area: 2007 information". Evox Facilities. 2007. Archived from the original on 23 July 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- "Londonderry". Collins Dictionary. n.d. Archived from the original on 4 April 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- "Derry/Londonderry". BBC. Archived from the original on 21 October 2007. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- "The Communications Market 2007" (PDF). Ofcom. p. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- DERRY REGIONAL CITY – Business Investment. Retrieved 1 November 2008. Archived 29 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Library Ireland Archived 8 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine – Sketches of Olden Days in Northern Ireland

- Anthony David Mills (6 November 2003). A Dictionary of British Place-Names. Oxford University Press. pp. 430–. ISBN 978-0-19-852758-9. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- Ryan Ver Berkmoes; Oliver Berry; Geert Cole; David Else (1 September 2009). Western Europe. Lonely Planet. p. 704. ISBN 978-1-74104-917-6. Archived from the original on 11 September 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- "What's in a name?". Derry Journal. 2 October 2009. Archived from the original on 21 January 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- Statistical Classification and Delineation of Settlements

- Brian Lacy (Editor), Archaeological Survey of County Donegal, p. 1. Donegal County Council, Lifford, 1983.

- BBC News (15 July 2010). "Londonderry named the UK City of Culture". BBC News. Archived from the original on 10 September 2010. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- Palmer, Robert. "The race is on to find UK's first 'City of Culture' for 2013". The National Archives. Archived from the original on 12 May 2010. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- "Derry City Council, Re Application for Judicial Review [2007] NIQB 5". Derry City Council. 25 January 2007. Archived from the original on 3 September 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- "Stroke City to remain Londonderry". BBC. 25 January 2007. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- "City name row lands in High Court". BBC News. 6 December 2006. Archived from the original on 7 April 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- "Derry City Council – High Court Provides Clarification on City's Name". Derrycity.gov.uk. 25 January 2007. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- Equality Impact Assessments Derry City Council website Archived 2 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Draft EQIA, Appendix pp.91–2

- McMahon, Damien (26 February 2010). "Report of Town Clerk and Chief Executive to Special Council Meeting". Archived from the original on 10 July 2007. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- McDaid, Brendan (24 July 2015). "New 'Derry' name bid 'disgusting', claim DUP". Derry Journal. Archived from the original on 25 July 2015. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- "Education/Oideachas". BBC. Archived from the original on 26 June 2007. Retrieved 14 July 2007.

- Hudson, John. "Londonderry". The British Library. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- Curl, James Stevens (2001). "The City of London and the Plantation of Ulster". BBCi History Online. Archived from the original on 13 September 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- "Aspects of Sectarian Division in Derry Londonderry – First public discussion: The Name Of this City?". Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- Kuusisto-Arponen, Anna-Kaisa (2001). "The end of violence and introduction of 'real' politics: Tensions in peaceful Northern Ireland". Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography. 83 (3): 121–130. doi:10.1111/j.0435-3684.2001.00100.x. JSTOR 491073.

- War zone language: linguistic aspects of the conflict in Northern Ireland by Cordula Hawes-Bilger (ISBN 978-3-7720-8200-9), page 100

- McCafferty, Kevin (2001). Ethnicity and Language Change: English in (London)Derry, Northern Ireland. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 978-1588110022.

- "Irish Rail network showing 'Derry'". Iarnród Éireann. Archived from the original on 18 November 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- Carroll, Stephen (9 April 2009). "Derry-born can choose city's name on passport". Irish Times. Archived from the original on 13 October 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- Davenport, Fionn; Beech, Charlotte; Downs, Tom; Hannigan, Des; Parnell, Fran; Wilson, Neil (2006). Ireland (7th ed.). London: Lonely Planet. p. 625. ISBN 978-1-74059-968-9.

Derry name republic.

- "Londonderry Chamber of Commerce". Londonderrychamber.co.uk. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- Change of District Name (Derry) Order 1984

- Sections 7, 8 and 132 of the Local Government Act (Northern Ireland) 1972 (Eliz II 20 & 21 c.9)

- "The Walled City Experience". Northern Ireland Tourist Board. Archived from the original on 20 April 2008. Retrieved 4 September 2008.

- The One Show, BBC1, 15 July 2010

- Lloyd, Chris (10 July 2015). "It's a long way to Londonderry..." The Northern Echo. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- "Web Development Belfast | Web solutions Ireland | Biznet IIS Northern Ireland". Brilliantireland.com. Archived from the original on 21 August 2008. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- "Antrim and Derry". Roughguides.com. Archived from the original on 22 July 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- "County Derry, Northern Ireland – Londonderry". Irelandwide.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- "Derry City Walls Conservation Plan. pdf doc. p19" (PDF).

- Historic Walls of Derry Archived 27 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine Discover Northern Ireland website

- Lacey, Brian (1999). Discover Derry. City Guides. Dublin: The O'Brien Press Ltd. ISBN 978-0-86278-596-3.

- "History of Derry". www.geographia.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- "King ponders plantation". www.irishtimes.com/. Archived from the original on 26 October 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- Brian Lacy, Archaeological Survey of County Donegal, p. 1. Donegal County Council, Lifford, 1983.

- "Walls Constructed". Derry's Walls. Guildhall Press. 2005–2008. Archived from the original on 24 February 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- "World Facts Index > United Kingdom > Londonderry". worldfacts.us. 2005. Archived from the original on 25 September 2006. Retrieved 5 September 2006.

- "BRIEF HISTORY OF ST COLUMB'S CATHEDRAL LONDONDERRY". www.stcolumbscathedral.org. Archived from the original on 4 January 2009. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- Johnson, James H. (1957). "The population of Londonderry during the Great Irish Famine". The Economic History Review. 10 (2): 273–285. doi:10.2307/2590863. JSTOR 2590863.

- Page 67 "Derry beyond the walls" by SDLP politician John Hume

- http://www.mccorkellline.com/ Archived 4 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine McCorkell Line

- Lambert, Tim. "A Brief History of Derry". Local Histories.org. Archived from the original on 6 April 2008. Retrieved 28 March 2008.

- JOYCE, JOE (24 June 2009). "June 24th, 1920: Pitched battles on the streets of Derry". www.irishtimes.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- "This is a chronology of Irish War of Independence". saoirse.21.forumer.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- Cullen, Ian (13 October 2008). "Derry was 'best kept secret' in Battle of the Atlantic". Derry Journal. Archived from the original on 21 January 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- "BBC Online – Northern Ireland – Radio Foyle". Bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "World War Two in Derry". Culturenorthernireland.org. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Chicago Tribune – Historical Newspapers".

- "The U-boat surrender". www.secondworldwarni.org. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- Explaining Northern Ireland: broken images by John McGarry, Brendan O'Leary (ISBN 978-0631183495), pages 205–206

- Race and inequality: world perspectives on affirmative action by Elaine Kennedy-Dubourdieu (ISBN 978-0754648390), page 108

- The Irish Catholic diaspora in America by Lawrence John McCaffrey (ISBN 978-0813208961), page 168

- "Discrimination – Chronology of Important Events". cain.ulst.ac.uk. 6 January 2009. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- Whyte, John (1983). "How much discrimination was there under the unionist regime, 1921–68?". In Gallagher, Tom; O'Connell, James (eds.). Contemporary Irish Studies. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-0919-8. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- "A whale of a time". BBC Radio Foyle. Archived from the original on 6 February 2009. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- The blazon runs as follows: Sable, a human skeleton Or seated upon a mossy stone proper, and in dexter chief a castle triple-towered argent; on a chief also argent a cross gules, thereon a harp Or, and in the first quarter a sword erect gules.

- Letters Patent certifying the arms of the City of Londonderry issued to Derry City Council, sealed by Garter and Norroy and Ulster Kings of Arms dated 30 April 2003

- Vinycomb, John (1895). "The Seals and Armorial Insignia of Corporate and Other Towns in Ulster". The Ulster Journal of Archaeology. 1 (2): 117–9. JSTOR 20563546.

- 'Geoghehan, Arthur Gerald (1864). "A Notice of the Early Settlement of Londonderry by the English, &c". The Journal of the Kilkenny and South-East of Ireland Archaeological Society. 5 (1): 155–6. JSTOR 25502656.

- L E Rothwell, An inquiry initiated by Derry City Council into the ensigns armourial and related matters of the City of Londonderry

- Letters Patent ratifying and confirming the arms of the City of Londonderry sealed by Garter and Norroy & Ulster Kings of Arms dated 28 April 1952

- "Derry Slopes Landscape". DOENI. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- "History–The Bogside". Museum of Free Derry. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- Wilson, David (12 February 2010). "Concerns over Lough Foyle bird numbers". Derry Journal. Archived from the original on 14 February 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- "Ness Country Park". DOENI. Archived from the original on 29 January 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- "Prehen Wood". Northern Ireland Tourist Board. Archived from the original on 28 February 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- "Airport guides climate page". Derry-ldy.airports-guides.com. 5 January 2012. Archived from the original on 27 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Station Locations". MetOffice. Archived from the original on 2 July 2001.

- "Station Locations". MetOffice. Archived from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "1995 minimum". tutiempo.

- "Ballykelly SAMOS 1981–2010". Met Office. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- "Census 2011 – Population and Household Estimates for Northern Ireland". Northern Ireland Statistics & Research Agency. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- "Statistics press notice: Mid-year population estimates Northern Ireland (2006)" (PDF). Northern Ireland Statistics & Research Agency. 31 July 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 June 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- "Londonderry population movement from West bank to East bank" (PDF). 11 January 1979. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 May 2014. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- "Note of a meeting between Secretary of State and William Ross Unionist MP" (PDF). Public Records Office of Northern Ireland. 6 November 1978. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 May 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- Mullen, Kevin (31 January 2013). "Catholics outnumber Protestants on both banks of the Foyle". Londonderry Sentinel. Archived from the original on 9 February 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- "Catholics urged to support neighbours". BBC News. 18 October 2006. Retrieved 28 August 2008.