Greyhound racing in the United Kingdom

Greyhound racing is a sport in the United Kingdom. The industry uses a Parimutuel betting tote system with on-course and off-course betting available, with a turnover of £75,100,000.[1]

Attendances peaked in 1946 at around 70 million and totalisator turnover reaching £196,431,430.[2] Attendances have declined to less than 2 million in 2017. As of 2 August 2020 there are 20 licensed stadiums in the UK (excluding Northern Ireland) and three independent stadiums (unaffiliated to a governing body).

History

Modern greyhound racing has evolved from a form of hunting called coursing, in which a dog runs after a live game animal – usually a rabbit or hare. The first official coursing meeting was held in 1776 at Swaffham, Norfolk. The rules of the Swaffham Coursing Society specified that only two greyhounds were to course a single hare and that the hare was to be given a head start of 240 yards.

Coursing by proxy with an artificial lure was introduced at Hendon, on September 11, 1876. Six dogs raced over a 400-yard straight course, chasing an artificial hare. This was the first attempt to introduce mechanical racing to the UK; however it did not catch on at the time.[3]

The oval track and mechanical hare were introduced to Britain in 1926, by Charles Munn, an American, in association with Major Lyne-Dixson, a key figure in coursing. Finding other supporters proved to be rather difficult, and with the General Strike of 1926 looming, the two men scoured the country to find others who would join them. Eventually they met Brigadier-General Critchley, who in turn introduced them to Sir William Gentle.[4] Between them they raised £22,000 and launched the Greyhound Racing Association.[5] On July 24, 1926, in front of 1,700 spectators, the first modern greyhound race in Great Britain took place at Belle Vue Stadium, where seven greyhounds raced round an oval circuit to catch an electric artificial hare.[6] They then hurried to open tracks in London at the White City Stadium and Harringay Stadium.[6]

The first three years of racing were successful financially, with attendances of 5.5 million in 1927, 13.7 million in 1928 and 16 million in 1929.[7]

Racing

The greyhound racing industry in Great Britain currently falls under two sectors: that registered by the Greyhound Board of Great Britain (GBGB),[8] and a sector known as 'independent racing' or 'flapping' which is unaffiliated to a governing body.

Registered racing

Registered racing in Great Britain is regulated by the Greyhound Board of Great Britain (GBGB) and has been UKAS accredited since 2010.[9] All in the registered sector are subject to the GBGB Rules of Racing [10] and the Directions of the Stewards, who set the standards for greyhound welfare and racing integrity, from racecourse facilities and trainers' kennels to retirement of greyhounds. There are Stewards' inquiries, and then disciplinary action is taken against anyone found failing to comply.[11]

The registered sector consists of 20 racecourses and approximately 880 trainers, 4,000 kennel staff and 860 racecourse officials. Greyhound owners number 15,000 with approximately 10,000 greyhounds registered annually for racing.[1]

Independent racing

Independent racing, also known as 'flapping', is held at three racecourses. The numbers of trainers, kennel staff, owners and greyhounds involved in independent racing is unknown because there is no requirement for central registration or licensing, and no code of practice. In England, standards for welfare and integrity are set by local government, but there is no governing or other regulatory body.

Stadiums

In the 1940s, there were seventy seven licensed tracks and over two hundred independent tracks in the United Kingdom, of which thirty three were in London.[2][12] Now there are 22 registered and three independent stadiums.

Registered stadiums

There are 20 active Greyhound Board of Great Britain (GBGB) registered stadiums in the UK,[13] with twenty in England and one in Scotland. There are no tracks in Wales, and Northern Irish tracks do not come under the control of the GBGB.

- Brighton and Hove Stadium, Brighton and Hove

- Central Park Stadium, Sittingbourne

- Crayford Stadium, London

- Doncaster Stadium, Doncaster

- Harlow Stadium, Harlow

- Henlow Stadium, Stondon

- Kinsley Stadium, Kinsley

- Monmore Green Stadium, Wolverhampton

- Newcastle Stadium, Newcastle upon Tyne

- Nottingham Stadium, Nottingham

- Owlerton Stadium, Sheffield

- Pelaw Grange, Chester-le-Street

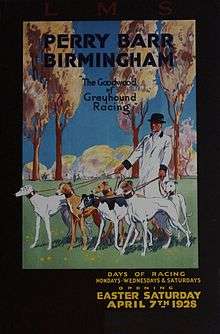

- Perry Barr Stadium, Birmingham

- Poole Stadium, Poole

- Romford Stadium, London

- Shawfield Stadium, Shawfield

- Sunderland Stadium, Sunderland

- Swindon Stadium, Swindon

- Towcester, Towcester

- Yarmouth Stadium, Great Yarmouth

Independent stadiums

There are also three active independent stadiums:

Competitions

There are many types of competitions in Britain,[14] with prize money reaching £15,737,122.[1]

Greyhound Derby This race must have minimum prize money of £50,000. The competition has six rounds and attracts around 180 entries each year. There are two derbys in Britain: the Scottish Greyhound Derby held at Shawfield Stadium, and the English Greyhound Derby formerly held at Wimbledon and Towcester, although both of these tracks have closed in recent years. The 2019 competition will be held at Nottingham. In addition, the Irish Greyhound Derby, held at Shelbourne Park, is open to British greyhounds. There used to be a Welsh Greyhound Derby but the event finished in 1977 after the Arms Park track in Cardiff closed. In 2010 the Northern Irish Derby was introduced.[15]

Category One Race These races must have minimum prize money of £12,500. They can be run between one and four rounds but must be completed within a 15-day period, except for special circumstances. In any event the competition must be completed within 18 days. Category One races replaced competitions called classic races in the 1990s.

Category Two Race These races must have minimum prize money of £5,000. They can be run with one, two or three rounds but must be completed within a 15-day period.

Category Three Race These races must have minimum prize money of £1,000. They can be run over one or two rounds and within a nine-day period. A category three race can be staged over one day but must have minimum prize money of £500.

Invitation Race A special type of open race usually staged by the promoter in support on the night of other opens. This will be proposed to the committee by the Greyhound Board or by a promoter, with the racers being invited into the competition rather than the usual process. The minimum prize money for these races is £750.

Minor Open Race This is any other open race. The minimum added money for these races is £150.

Graded racing

This is any other race staged at a track, and prize money is varied. This kind of racing is the core of most stadiums and some of the racing can be viewed in betting shops on the Bookmakers Afternoon Greyhound Service (BAGS). The Racing Manager selects the greyhounds based on ability and organises them into traps (called seeding) and classes (usually 1-9) with grade 1 being the best class.[10]

- A class represent standard races

- B class represent standard races+

- D class represent sprint races

- S class represent staying races

- M class represent marathon races

- P class represent puppy races

- H class represent hurdle races

- Hcp class represents handicap races

+ Only used if a track has an alternative standard distance.[10]

Racing jacket colours and starting traps

Greyhound racing in Britain has a standard colour scheme. The starting traps (equipment that the greyhound starts a race in) determines the colour. There are currently no tracks that feature races with eight greyhounds.[10]

- Trap 1 = Red with White numeral

- Trap 2 = Blue with White numeral

- Trap 3 = White with Black numeral

- Trap 4 = Black with White numeral

- Trap 5 = Orange with Black numeral

- Trap 6 = Black & White Stripes with Red numeral

- Trap 7 = Green with Red numeral

- Trap 8 = Yellow and Black with White numeral

A racing jacket worn by a reserve bears an additional letter 'R' prominently on each side.[10]

Racing greyhounds and welfare

Treatment of racing greyhounds

Greyhound racing at registered stadiums in Great Britain is regulated by the Greyhound Board of Great Britain (GBGB). In Britain greyhounds are not kept at the tracks and are instead housed in the kennels of trainers and transported to the tracks to race. Licensed kennels have to fall within specific guidelines and rules[10] and are checked by officials to make sure the treatment of racing greyhounds is within the rules.[10] In 2018 licensing and inspecting trainer's kennels was conducted through the government-approved, UKAS accredited method.[16] Greyhounds' health and condition are checked at the track by the veterinary surgeon before they are permitted to race and drugs tests are conducted.[10]

Retirement

After the greyhounds are no longer able to race, owners may keep the dog for breeding or as pets, or they can send them to greyhound adoption groups. The Greyhound Board of Great Britain (GBGB) have introduced measures to locate where racing greyhounds reside after they have retired from racing and from 2017 has been available to the public.[17] Concern among welfare groups is the well being of some racing greyhounds who are not adopted upon their retirement, and that they may subsequently be put down or sold by their owners, however the GBGB require all owners to sign a retirement form indicating the retirement plans.[18]

The main greyhound adoption organisation in Britain is the Retired Greyhound Trust (RGT). The RGT is a charity but is partly funded by the British Greyhound Racing Fund (BGRF), who gave funding of £1,400,000 in 2015 and rehomed 4,000 greyhounds in 2016.[19] [20] In recent years the racing industry has made significant progress in establishing programmes for the adoption of retired racers. Many race tracks have established their own adoption programmes[21] in addition to actively cooperating with private adoption groups throughout the country.

There are also many independent organisations which find homes for retired Greyhounds including Forever Hounds,[22] Greyhound Gap,[23] Celia Cross Greyhound Trust[24] and Bark Inn Kennels.[25] Several independent rescue and homing groups receive some funding from the industry but mainly rely on public donations. In 2016, 1,500 greyhounds were rehomed by independent groups. In 2018 several tracks introduced a scheme whereby every greyhound is found a home by the track, these include Kinsley and Doncaster.[26][27]

Injuries

Due to the physical stresses of racing, many greyhounds will at some point sustain an injury.[28] As of 2017 all injury data was made publicly available and independently verified.[29]

Injuries in the racing greyhound are common[30][31] because of several factors including the speed at which the dogs race, track design including the angle and banking of the bends, and the track surface.[32] Several studies have been conducted explaining the types of injury that can occur.[30][33] Most injuries, including broken hocks are treatable,[34][35][36] but greyhounds have been euthanized at tracks for these injuries, the most common reason for euthanasia was fracture of the right tarsus[37] From 2017 the number of greyhounds euthanized was made public.[38]

Drugs

The Greyhound Board of Great Britain (GBGB) actively works to prevent the spread of drug usage within the registered greyhound racing sector.[39] Attempts are made to recover urine samples from all six greyhounds in a race. Greyhounds from which samples can not be obtained for a certain number of consecutive races are subject to being ruled off the track. If a positive sample is found, violators are subject to penalties and loss of their racing licenses by the Greyhound Board of Great Britain (GBGB). The trainer of the greyhound is at all times the "absolute insurer" of the condition of the animal. The trainer is responsible for any positive test regardless of how the banned substance has entered the greyhound's system.[40] Due to the increased practice of random testing, the number of positive samples has decreased.[39]

Controversy

Isolated incidents have occurred that resulted in national newspaper articles. In 2012, there was a report of greyhound cadavers being sold to research labs used for students to practice upon. Liverpool University Animal Training School has stated that it received the remains of dogs put to sleep because it was essential to improving animal health and welfare.[41] Charles Pickering, a greyhound breeder from Lincolnshire was exposed offering 'slow' dogs to the Liverpool school as live subjects. The Greyhound Board of Great Britain Disciplinary Committee found Pickering in breach of rules 18(i), (ii) and (iii), 152 (i) and (ii), 174(vi) and 174(xiv) (a) and (b) and ordered that he be made a Warned Off person (life ban) and fined the sum of £5,000.[42][43] Greyhounds were sent to builder David Smith, in the North East of England who destroyed greyhounds with a captive bolt gun, he was unqualified to do so.[44] Smith faced a fine and jail sentence[45] and anyone found to have sent a greyhound to him was warned off for life.[46]

References

- "About". Greyhound Board of Great Britain. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- Particulars of Licensed tracks, table 1 Licensed Dog Racecourses. Licensing Authorities. 1946.

- "greyhound racing in Encyclopedia of Britain by Bamber Gascoigne". historyworld.net.

- Genders, Roy (1981). the Encyclopaedia of Greyhound Racing. Pelham Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7207-1106-6.

- "Greyhound Racing History". greyhoundracinghistory.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2015-04-13. Retrieved 2015-04-09.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-09-28. Retrieved 2008-10-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Remember When - January 1930". Greyhound Star. 2012.

- "We are the governing body for licensed greyhound racing". Greyhound Board of Great Britain.

- "GBGB Press Release". Greyhound Star.

- "Rules of Racing". Greyhound Board of Great Britain.

- "Disciplinary Committee Hearings". Greyhound Board of Great Britain.

- "Going to the dogs". The Guardian. 2008-08-09. Retrieved 2017-08-25.

- "Our Racecourses". Greyhound Board of Great Britain.

- "Open Races". Greyhound Board of Great Britain.

- Genders, Roy (1990). NGRC book of Greyhound Racing. Pelham Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7207-1804-1.

- "Welfare and Care". Greyhound Board of Great Britain.

- "Welfare & Retirement". Greyhound Board of Great Britain.

- Second Report of Session 2015–16 (10 February 2016). "Greyhound welfare" (PDF). parliament.uk. Retrieved 27 Feb 2017.

- "Retirement Funding" (PDF). British Greyhound Racing Fund Limited.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-12-18. Retrieved 2008-10-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Forever Hounds Trust".

- "Greyhound Gap".

- "The Celia Cross Greyhound Trust".

- "Homepage". Bark Inn Kennels. Retrieved 2017-02-27.

- "KINSLEY MAKE WELFARE HISTORY". Greyhound Star. 2017-11-13.

- "NEW DONCASTER SCHEME RE-HOMES 77 DOGS IN FOUR MONTHS". Greyhound Star. November 2018.

- Morris, Darren (2009). Training and Racing the Greyhound.

- "Injury and Retirement Data". Greyhound Board of Great Britain. Archived from the original on 2018-03-16. Retrieved 2018-11-23.

- Molyneux, Jacqui (2005-05-01). "Vets on track: working as a greyhound vet". In Practice. 27 (5): 277–279. doi:10.1136/inpract.27.5.277. ISSN 2042-7689.

- Prole, J.H (1976). "A survey of racing injuries in the Greyhound". Journal of Small Animal Practice. 17 (4): 207–18. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.1976.tb06951.x. PMID 933469.

- Sicard, G.K (1999). "A survey of injuries at five greyhound racing tracks". Journal of Small Animal Practice. 40 (9): 428–32. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.1999.tb03117.x. PMID 10516949.

- Thesis: The nature, incidence and response to treatment of injuries to the distal limbs in the racing Greyhound. Guilliard M.J, 2012. Pages 2-6

- Boudrieau, RJ (1984). "Central tarsal bone fractures in the racing Greyhound: a review of 114 cases". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 184 (12): 1486–91. PMID 6735872.

- Guilliard, M. J. (2010-12-01). "Third tarsal bone fractures in the greyhound". Journal of Small Animal Practice. 51 (12): 635–641. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.2010.01004.x. ISSN 1748-5827. PMID 21121918.

- Johnson, KA (1989). "Screw fixation of accessory carpal fractures in racing greyhounds: 12 cases (1981-1986)". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 194 (11): 1618–25. PMID 2753786.

- Thesis: Specialisation for fast locomotion:performance, cost and risk. Hercock, C.A. 2010 page 16-17

- "Greyhound welfare: Second Report of Session 2015–16" (PDF). House of Commons Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-09-28. Retrieved 2008-10-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-09-28. Retrieved 2008-10-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Qureshi, Yakub (27 April 2010). "30 Injured Grehounds Put Down at Dog Track". Manchester Evening News. Manchester. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- Foggo, Daniel (2008-05-11). "Greyhound breeder offers slow dogs to be killed for research - The Sunday Times". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- Jeory, Ted (30 May 2010). "Agony of Caged Greyhounds". Daily Express. London. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- Foggo, Daniel (16 July 2006). "Killing field of the dog racing industry - The Sunday Times". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- "Greyhound killer to face tougher sentence". The Guardian. 16 February 2007.

- "Editors Chair". Greyhound Star. November 2017.

External links

- Greyhound Board of Great Britain (GBGB)

- Retired Greyhound Trust (RGT)

- British Greyhound Racing Fund (BGRF)

- Greyhound Data

- Greyhound Star

- National Coursing Club (NCC)

- Greyhound Trainers Association (GTA)

- Greyhound Breeders Forum

- Brighton Greyhound Owners Association Trust (BGOA)

- Romford Greyhound Owners Association Trust (RGOA)