Sevastopol

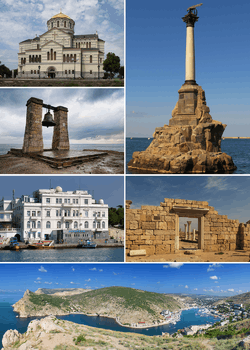

Sevastopol (Ukrainian, Russian: Севастополь; Crimean Tatar: Aqyar, Акъяр)[lower-alpha 1];[2] is the largest city on the Crimean Peninsula and a major Black Sea port. Since the Annexation of Crimea in 2014, Sevastopol has been administered as federal city of the Russian Federation. Nevertheless, Ukraine and majority of the United Nations member countries continue to regard Sevastopol as a city with special status within Ukraine. The city has a Russian majority population, with smaller minorities of Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars.

Sevastopol | |

|---|---|

| |

Flag | |

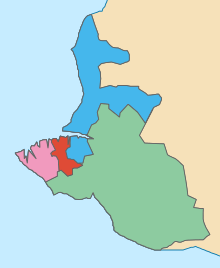

Orthographic projection of Sevastopol (in green) | |

Map of the Crimean Peninsula with Sevastopol highlighted | |

.svg.png) Sevastopol Location of Sevastopol within Crimea  Sevastopol Location of Sevastopol within Ukraine .svg.png) Sevastopol Location of Sevastopol within Russia  Sevastopol Sevastopol (Europe) | |

| Coordinates: 44°36′00″N 33°32′00″E | |

| Country | Disputed: |

| Status within Ukraine | City with special status |

| Status within Russia | Federal city |

| Founded | 1783 (237 years ago) |

| Government (de facto) | |

| • Governor | Mikhail Razvozhayev (acting) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 864 km2 (334 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 100 m (300 ft) |

| Population (2019) | |

| • Total | 443,211 |

| • Density | 510/km2 (1,300/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Sevastopolitan, Sevastopolian |

| Time zone | UTC+03:00 (MSK, de facto) |

| Postal code | 299000–299699 (Russian system) |

| Area code(s) | +7-8692 (Russian system)[1] |

| License plate | 92 (Russian system) |

| Website | sevastopol |

Sevastopol has a population of 393,304 (2014 Census),[3] concentrated mostly near the Sevastopol Bay and surrounding areas. The location and navigability of the city's harbors have made Sevastopol a strategically important port and naval base throughout history. The city has been a home to the Russian Black Sea Fleet, which is why it was considered as a separate city in Crimea of significant military importance and was once operated by the Soviet Union as a closed city.

Although relatively small at 864 square kilometres (334 sq mi), Sevastopol's unique naval and maritime features have been the basis for a robust economy. The city enjoys mild winters and moderate warm summers, characteristics that help make it a popular seaside resort and tourist destination, mainly for visitors from the former Soviet republics. The city is also an important centre for marine biology research. In particular, dolphins have been studied and trained in the city by the military since the end of World War II.

Etymology

The name of Sevastopolis was originally chosen in the same etymological trend as other cities in the Crimean peninsula; it was intended to express its ancient Greek origins. It is a compound of the Greek adjective, σεβαστός (sebastos, 'venerable', Byzantine Greek pronunciation: [se.vasˈtos]) and the noun πόλις (pólis) ('city'). Σεβαστός is the traditional Greek equivalent (Sebastian) of the Roman honorific Augustus, originally given to the first emperor of the Roman Empire, Augustus and later awarded as a title to his successors.

Despite its Greek origin, the name is not from Ancient Greek times. The city was probably named after Empress ("Augusta") Catherine II of the Russian Empire who founded Sevastopol in 1783. She visited the city in 1787, accompanied by Joseph II, the Emperor of Austria, and other foreign dignitaries.

In the west of the city, there are well-preserved ruins of the ancient Greek port city of Chersonesos, founded in the 5th (or 4th) century BC by settlers from Heraclea Pontica. This name means "peninsula", reflecting its immediate location. It is not related to the ancient Greek name for the Crimean Peninsula as a whole: Chersonēsos Taurikē ("the Taurian Peninsula").

The name of the city is spelled as:

- In English, the current prevalent spelling of the name is Sevastopol; the previously common spelling Sebastopol is still used by some publications such as The Economist. In English, the current spelling also has the pronunciation /səˈvæstəpoʊl/ or /ˌsɛvəˈstoʊpəl/,[4] while the former spelling has the pronunciation /sɪˈbæstəpəl, -pɒl/[5] or /səˈbæstəpoʊl, -pɒl/.[6]

- Ukrainian: Севастополь; Russian: Севасто́поль, pronounced [sewɐˈstɔpolʲ] in Ukrainian and [sʲɪvɐˈstopəlʲ][7] in Russian.

- Crimean Tatar: Aqyar or Sivastopol, pronounced [aqˈjar].

History

Chersonesus founded in 6th century BC

Hellenic Colonies 6th century BC – 480 BC

Bosporan Kingdom 480 BC – 107 BC

Kingdom of Pontus 107 BC – 63 BC

Roman Republic 63 BC–27 BC

Roman Empire 27 BC – 330

Byzantine Empire 330–1204

Empire of Trebizond 1204–1461

Principality of Theodoro 1461–1475

Crimean Khanate 1475–1783 (Ottoman vassal from 1478 to 1774)

Russian Empire 1783–1917

Founded as Sevastopol in 1783

Russian Republic 1917

Russian SFSR (Soviet Union) 1917–1942

Nazi Germany 1942–1944

Russian SFSR (Soviet Union) 1944–1954

Ukrainian SSR (Soviet Union) 1954–1991

Ukraine 1991–2014 (de jure – present)

Russian Federation 2014–present

In the 6th century BC, a Greek colony was established in the area of the modern-day city. The Greek city of Chersonesus existed for almost two thousand years, first as an independent democracy and later as part of the Bosporan Kingdom. In the 13th and 14th centuries, it was sacked by the Golden Horde several times and was finally totally abandoned. The modern day city of Sevastopol has no connection to the ancient and medieval Greek city, but the ruins are a popular tourist attraction located on the outskirts of the city.

Part of the Russian Empire

.jpg)

Sevastopol was founded in June 1783 as a base for a naval squadron under the name Akhtiar[8] (White Cliff),[9] by Rear Admiral Thomas MacKenzie (Foma Fomich Makenzi), a native Scot in Russian service; soon after Russia annexed the Crimean Khanate. Five years earlier, Alexander Suvorov ordered that earthworks be erected along the harbour and Russian troops be placed there. In February 1784, Catherine the Great ordered Grigory Potemkin to build a fortress there and call it Sevastopol. The realisation of the initial building plans fell to Captain Fyodor Ushakov who in 1788 was named commander of the port and of the Black Sea squadron.[10] It became an important naval base and later a commercial seaport. In 1797, under an edict issued by Emperor Paul I, the military stronghold was again renamed to Akhtiar. Finally, on 29 April (10 May), 1826, the Senate returned the city's name to Sevastopol.

One of the most notable events involving the city is the Siege of Sevastopol (1854–55) carried out by the British, French, Piedmontese, and Turkish troops during the Crimean War, which lasted for 11 months. Despite its efforts, the Russian army had to leave its stronghold and evacuate over a pontoon bridge to the north shore of the inlet. The Russians chose to sink their entire fleet to prevent it from falling into the hands of the enemy and at the same time to block the entrance of the Western ships into the inlet. When the enemy troops entered Sevastopol, they were faced with the ruins of a formerly glorious city.

A panorama of the siege originally was created by Franz Roubaud. After its destruction in 1942 during World War II, it was restored and is currently housed in a specially constructed circular building in the city. It portrays the situation at the height of the siege, on 18 June 1855.

World War II

During World War II, Sevastopol withstood intensive bombardment by the Germans in 1941–42, supported by their Italian and Romanian allies during the Battle of Sevastopol. German forces used railway artillery—including history's largest-ever calibre railway artillery piece in battle, the 80-cm calibre Schwerer Gustav—and specialised mobile heavy mortars to destroy Sevastopol's extremely heavy fortifications, such as the Maxim Gorky Fortresses. After fierce fighting, which lasted for 250 days, the supposedly untakable fortress city finally fell to Axis forces in July 1942. It was intended to be renamed to "Theoderichshafen" (in reference to Theoderic the Great and the fact that the Crimea had been home to Germanic Goths until the 18th or 19th century) in the event of a German victory against the Soviet Union, and like the rest of the Crimea was designated for future colonisation by the Third Reich. It was liberated by the Red Army on 9 May 1944 and was awarded the Hero City title a year later.

Sevastopol as part of Ukrainian SSR

During the Soviet era, Sevastopol became a so-called "closed city". This meant that any non-residents had to apply to the authorities for a temporary permit to visit the city.

On 29 October 1948, the Presidium of Supreme Council of the Russian SFSR issued a ukase (order) which confirmed the special status of the city.[11] Soviet academic publications since 1954, including the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, indicated that Sevastopol, Crimean Oblast was part of the Ukrainian SSR (Great Soviet Encyclopedia 1976, Vol.23. pp 104).[9]

In 1954, under Nikita Khrushchev, both Sevastopol and the remainder of the Crimean peninsula were administratively transferred from being territories within the Russian SFSR to being territories administered by the Ukrainian SSR. Administratively, Sevastopol was a municipality excluded from the adjacent Crimean Oblast. The territory of the municipality was 863.5 km² and it was further subdivided into four raions (districts). Besides the City of Sevastopol proper, it also included two towns—Balaklava (having had no status until 1957), Inkerman, urban-type settlement Kacha, and 29 villages.[12]

At the 1955 Ukrainian parliamentary elections on 27 February, Sevastopol was split into two electoral districts, Stalinsky and Korabelny (initially requested three Stalinsky, Korabelny, and Nakhimovsky).[11] Eventually, Sevastopol received two people's deputies of the Ukrainian SSR elected to the Verkhovna Rada A. Korovchenko and M. Kulakov.[11][13]

In 1957, the town of Balaklava was incorporated into Sevastopol.

After Soviet dissolution

On 10 July 1993, the Russian parliament passed a resolution declaring Sevastopol to be "a federal Russian city".[14] At the time, many supporters of the president, Boris Yeltsin, had ceased taking part in the Parliament's work.[15] On 20 July 1993 the United Nations Security Council denounced the decision of the Russia parliament. According to Anatoliy Zlenko, it was for the first time that the council had to review actions and come up with qualification of them for a legislative body.[11]

On 14 April 1993, the Presidium of the Crimean Parliament called for the creation of the presidential post of the Crimean Republic. A week later, the Russian deputy, Valentin Agafonov, stated that Russia was ready to supervise the referendum on Crimean independence and include the republic as a separate entity in the CIS. On 28 July 1993, one of the leaders of the Russian Society of Crimea, Viktor Prusakov, stated that his organisation was ready for an armed mutiny and establishment of the Russian administration in Sevastopol.

In September, the commander of the joint Russian-Ukrainian Black Sea Fleet, Eduard Baltin, accused Ukraine of converting some of his fleet and conducting an armed assault on his personnel, and threatened to take countermeasures of placing the fleet on alert. (In June 1992, the Russian president Boris Yeltsin and the Ukrainian president Leonid Kravchuk had agreed to divide the former-Soviet Black Sea Fleet between Russia and Ukraine. Eduard Baltin had been appointed commander of the Black Sea Fleet by Yeltsin and Kravchuk on 15 January 1993.)

In May 1997, Russia and Ukraine signed the Peace and Friendship Treaty, ruling out Moscow's territorial claims to Ukraine.[16] A separate agreement established the terms of a long-term lease of land, facilities, and resources in Sevastopol and the Crimea by Russia.

The ex-Soviet Black Sea Fleet and its facilities were divided between Russia's Black Sea Fleet and the Ukrainian Naval Forces. The two navies co-used some of the city's harbours and piers, while others were demilitarised or used by either country. Sevastopol remained the location of the Russian Black Sea Fleet headquarters with the Ukrainian Naval Forces Headquarters also in the city. A judicial row periodically continued over the naval hydrographic infrastructure both in Sevastopol and on the Crimean coast (especially lighthouses historically maintained by the Soviet or Russian Navy and also used for civil navigation support).

As in the rest of the Crimea, Russian remained the predominant language of the city, although following the independence of Ukraine there were some attempts at Ukrainisation with very little success. The Russian society in general and even some outspoken government representatives never accepted the loss of Sevastopol and tended to regard it as temporarily separated from the homeland.[17]

In July 2009, the chairman of the Sevastopol city council, Valeriy Saratov (Party of Regions)[18] stated that Ukraine should increase the amount of compensation it is paying to the city of Sevastopol for hosting the foreign Russian Black Sea Fleet, instead of requesting such obligations from the Russian government and the Russian Ministry of Defense in particular.[19]

On 27 April 2010, Russia and Ukraine ratified the Russian Ukrainian Naval Base for Gas treaty, extending the Russian Navy's lease of Crimean facilities for 25 years after 2017 (through 2042) with an option to prolong the lease in 5-year extensions. The ratification process in the Ukrainian parliament encountered stiff opposition and erupted into a brawl in the parliament chamber. Eventually, the treaty was ratified by a 52% majority vote—236 of 450. The Russian Duma ratified the treaty by a 98% majority (without incident).[20]

Sevastopol was annexed by Russia in 2014 with the rest of Crimea and since then has been administered as the federal city of Sevastopol.[21]

Geography

The city of Sevastopol is located at the southwestern tip of the Crimean peninsula in a headland known as Heracles peninsula on a coast of the Black Sea. The city is designated a special city-region of Ukraine which besides the city itself includes several of its outlying settlements. The city itself is concentrated mostly at the western portion of the region and around the long Bay of Sevastopol. This bay is a ria, a river canyon drowned by Holocene sea-level rise, and the outlet of Chorna River. Away in a remote location southeast of Sevastopol is located the former city of Balaklava (since 1957 incorporated within Sevastopol), the bay of which in Soviet times served as a main port for the Soviet diesel-powered submarines.

The coastline of the region is mostly rocky, in a series of smaller bays, a great number of which are located within the Bay of Sevastopol. The biggest of them are the Southern Bay (within Bay of Sevastopol), the Archer Bay, a gulf complex that consists of the Deergrass Bay, the Bay of Cossack, the Salty Bay, and many others. There are over thirty bays in the immediate region.

Through the region flow three rivers: the Belbek, Chorna, and Kacha. All three mountain chains of Crimean mountains are represented in Sevastopol, the southern chain by the Balaklava Highlands, the inner chain by the Mekenziev Mountains, and the outer chain by the Kara-Tau Upland (Black Mountain).

Climate

Sevastopol has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification: Cfa),[22] due to summer mean straddling 22 °C (72 °F) that is bordering on a four-season oceanic climate, with cool winters and warm to hot summers.

The average yearly temperature is 15–16 °C (59–61 °F) during the day and around 9 °C (48 °F) at night. In the coldest months, January and February, the average temperature is 5–6 °C (41–43 °F) during the day and around 1 °C (34 °F) at night. In the warmest months, July and August, the average temperature is around 26 °C (79 °F) during the day and around 19 °C (66 °F) at night. Generally, summer/holiday season lasts 5 months, from around mid-May and into September, with the temperature often reaching 20 °C (68 °F) or more in the first half of October.

The average annual temperature of the sea is 14.2 °C (58 °F), ranging from 7 °C (45 °F) in February to 24 °C (75 °F) in August. From June to September, the average sea temperature is greater than 20 °C (68 °F). In the second half of May and first half of October; the average sea temperature is about 17 °C (63 °F). The average rainfall is about 400 millimetres (16 in) per year. There are about 2,345 hours of sunshine duration per year.[23]

| Climate data for Sevastopol | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 5.9 (42.6) |

6.0 (42.8) |

8.9 (48.0) |

13.6 (56.5) |

19.2 (66.6) |

23.5 (74.3) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.3 (79.3) |

22.4 (72.3) |

17.8 (64.0) |

12.3 (54.1) |

8.1 (46.6) |

15.9 (60.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.9 (37.2) |

2.8 (37.0) |

5.4 (41.7) |

9.8 (49.6) |

15.1 (59.2) |

19.5 (67.1) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.1 (71.8) |

18.1 (64.6) |

13.8 (56.8) |

8.8 (47.8) |

5.0 (41.0) |

12.1 (53.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −0.2 (31.6) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

2.0 (35.6) |

6.1 (43.0) |

11.1 (52.0) |

15.5 (59.9) |

18.2 (64.8) |

17.9 (64.2) |

13.9 (57.0) |

9.9 (49.8) |

5.4 (41.7) |

2.0 (35.6) |

8.5 (47.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 26 (1.0) |

25 (1.0) |

24 (0.9) |

27 (1.1) |

18 (0.7) |

26 (1.0) |

32 (1.3) |

33 (1.3) |

42 (1.7) |

32 (1.3) |

42 (1.7) |

52 (2.0) |

379 (15) |

| Average precipitation days | 6 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 31 |

| Source: pogodaiklimat.ru[24] | |||||||||||||

Politics and government

.jpg)

On 18 March 2014, the Kremlin announced that Sevastopol would become the third federal city in the Russian Federation, the two others being Moscow and St. Petersburg.

City State Administration

The executive power of Sevastopol is exercised by the Sevastopol City State Administration led by a chairman.[25] Since April 2014 the executive power is held by the Government of Sevastopol, led by the City Governor.

Legislature

Before 2014, the Sevastopol City Council was the legislature of Sevastopol and the mayor of Sevastopol was appointed by the Ukrainian central government. However, during the 2014 Crimean crisis, the pro-Russian City Council threw its support behind Russian citizen Alexei Chaly as the "people's mayor" and said it would not recognise orders from Kiev.[26][27]

After the Accession of Crimea to the Russian Federation, the Legislative Assembly of Sevastopol replaced the City Council and the mayor is appointed by the legislative branch on the nomination of the Russian President,[28] and officially the mayor is called the Governor of Sevastopol City.

Administrative and municipal divisions

Sevastopol is administratively divided into four districts.

Within the Russian municipal framework, the territory of the federal city of Sevastopol is divided into nine municipal okrugs and the Town of Inkerman. While individual municipal divisions are contained within the borders of the administrative districts, they are not otherwise related to the administrative districts.

Economy

Apart from navy-related civil facilities, Sevastopol hosts some other notable industries. An example is Stroitel,[29] one of the leading plastic manufacturers in Russia.

The city received millions of US Dollars in compensation for hosting the Russian Black Sea Fleet from the Russian and the Ukrainian government.

Industry

- Sevastopol Aircraft Plant, SMZ Sevastopol Shipyards (main at Naval Bay) & Inkerman Shipyards, Balaklava Bay Shipyard

- Impuls 2 SMZ

- Chornomornaftogaz § Chernomorneftegaz (Chjornomor), oil gas extraction, petrochemical, jack rigs and oil plantforms, LNG and oil tankers.

- AO FNGUP Granit subsidiary of Almaz Antej, (assemblation ?) overhaul and manutention of SAM and radar EW complexes, ADS services.

- Sevastopol (Parus SPriborMZ, Mayak, NPO Elektron, NPP Kvant, Tavrida Elektronik, Musson, other plants, industry)

- Sevastopol Economic Industrial Zone SevPZ (south SE area)

- Persej SMZ ship remont and floating dock yard plant (South Bay, Sevastopol)

- Sevastopol ship remont and floating docks yards (various)

- Various Mining and Metallurgy, Chemical Plants, and other industries around

- Agriculture, crops, rice wheat wines thea fruits, tobacco (lesser), other products . Fishing and farming .

- Mining, iron titanium manganese aluminium, calcite silicates and else, amethyst, other .

- Kerch bridge, Taurida highway, Sevastopol GasTES plus solar FV plants, gas and petro depots coal and materials, ports .

Infrastructure

There are seven types of transport in Sevastopol:

- Bus – 101 lines

- Trolleybus – 14 lines

- Minibus – 52 lines

- Cutter – 6 lines

- Ferry – 1 line

- Express-bus – 15 lines

- HEV-train{local, suburban route} – 1 route

- Airport – 1

Sevastopol Shipyard comprises three facilities that together repair, modernise, and re-equip Russian Naval ships and submarines.[30] The Sevastopol International Airport is used as a military aerodrome at the moment and being reconstructed to be used by international airlines.

Sevastopol maintains a large port facility in the Bay of Sevastopol and in smaller bays around the Heracles peninsula. The port handles traffic from passengers (local transportation and cruise), cargo, and commercial fishing. The port infrastructure is fully integrated with the city of Sevastopol and naval bases of the Black Sea Fleet.

Tourism

After World War II, Sevastopol was entirely rebuilt. Many top architects and civil engineers from Moscow, Leningrad, Kiev and other cities and thousands of workers from all parts of the USSR took part in the rebuilding process which was mostly finished by the mid-1950s. The downtown core situated on a peninsula between two narrow inlets, South Bay and Artillery Bay, features mostly Mediterranean-style, three-story residential buildings with columned balconies and Venetian-style arches, with retail and commercial spaces occupying the ground level. Some carefully restored landmarks date back to the early 20th century (e.g., the Art Nouveau Main Post Office on Bolshaya Morskaya St and the Art Museum on Nakhimovsky Prospect). It has been a long-time tradition for the residents of surrounding suburbs to spend summer evenings by coming to the downtown area for a leisurely stroll with their families along the avenues and boulevards encircling the Central Hill, under the Sevastopol chestnut trees, and usually ending up on the waterfront with its Marine Boulevard.

Due to its military history, most streets in the city are named after Russian and Soviet military heroes. There are hundreds of monuments and plaques in various parts of Sevastopol commemorating its military past.

Attractions include:

- Chersonessos National Archeological Reserve

- Sevastopol Art Museum named after the N.P. Kroshitskiy

- Sevastopol Museum of Local History

- Aquarium-Museum of the Institute of Biology of the Southern Seas of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine

- Dolphinarium of Sevastopol

- Sevastopol Zoo

- The Monument to the scuttled ships on the Marine Boulevard

- The Panorama Museum (The Heroic Defence of Sevastopol during the Crimean War)

- Malakhov Kurgan (Barrow) with its White Tower

- Admirals' Burial Vault

- The Black Sea Fleet Museum

- The Storming of Sapun-gora of 7 May 1944, the Diorama Museum (World War II)

- Naval museum complex "Balaklava", decommissioned underground submarine base, now opened to the public

- Cheremetieff brothers museum "Crimean war 1853–1856"

- Museum of the underground forces of 1942–1944

- Museum Historical Memorial Complex "35th Coastal Battery"

- The Naval Museum "Michael's battery"

- Fraternal (Communal) War Cemetery

Sevastopol Artillery Bay view.

Sevastopol Artillery Bay view. The seaside of Sevastopol.

The seaside of Sevastopol. St. Vladimir's Cathedral at 'the city hill'.

St. Vladimir's Cathedral at 'the city hill'. Saints Peter and Paul Cathedral.

Saints Peter and Paul Cathedral. View of the Northern side.

View of the Northern side. Old city cemetery.

Old city cemetery. Main railway station.

Main railway station. The Panorama Museum (The Heroic Defence of Sevastopol during the Crimean War).

The Panorama Museum (The Heroic Defence of Sevastopol during the Crimean War). The Storming of Sapun-gora of 7 May 1944, the Diorama Museum (World War II).

The Storming of Sapun-gora of 7 May 1944, the Diorama Museum (World War II). Entrance to Balaklava bay, 2010.

Entrance to Balaklava bay, 2010.

Education

Demographics

The population of Sevastopol proper is 443,211 (01.01.19),[31] making it the largest in the Crimean Peninsula. The city's agglomeration has about 600,000 people (2015). According to the Ukrainian National Census, 2001, the ethnic groups of Sevastopol include Russians (71.6%), Ukrainians (22.4%), Belarusians (1.6%), Tatars (0.7%), Crimean Tatars (0.5%), Armenians (0.3%), Jews (0.3%), Moldovans (0.2%), and Azerbaijanis (0.2%).[32]

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Vital statistics for 2015

- Births: 5 471 (13.7 per 1000)

- Deaths: 6 072 (15.2 per 1000)

Culture

There are many historical buildings in the central and eastern parts of the city and Balaklava, some of which are architectural monuments. The Western districts have modern architecture. More recently, numerous skyscrapers have been built. Balaklava Bayfront Plaza (on hold), currently under construction, will be one of the tallest buildings in Ukraine, at 173 m (568 ft) with 43 floors.[33]

After the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea the city's monument to Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny was removed and handed over to Kharkiv.[34]

Gallery

View of Sevastopol

View of Sevastopol Ships of the Black Sea Fleet docked in Sevastopol

Ships of the Black Sea Fleet docked in Sevastopol- Nakhimov Square

Palace of Culture

Palace of Culture Lunacharsky Theater

Lunacharsky Theater Artillery Bay

Artillery Bay

See also

- 2121 Sevastopol – asteroid discovered in 1971 by Soviet astronomer Tamara Mikhailovna Smirnova and named after the city.[35]

- Sebastopol, Victoria

Notes

- English: /ˌsɛvəˈstoʊpəl, -ˈstɒpəl, səˈvæstəpɒl, -pəl/ Ukrainian, Russian: Севасто́поль, tr. Sevastópolʹ, IPA: [sʲɪvɐˈstopəlʲ]; Ukrainian pronunciation: [seʋɐˈstɔpɔlʲ]

References

- "Севастополь перешел на российскую нумерацию". sevastopol.gov.ru.

- Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, Merriam-Webster.

- Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2014). "Таблица 1.3. Численность населения Крымского федерального округа, городских округов, муниципальных районов, городских и сельских поселений" [Table 1.3. Population of Crimean Federal District, Its Urban Okrugs, Municipal Districts, Urban and Rural Settlements]. Федеральное статистическое наблюдение «Перепись населения в Крымском федеральном округе». ("Population Census in Crimean Federal District" Federal Statistical Examination) (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- "definition: meaning, pronunciation and origin of the word". Oxford Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- "definition: meaning, pronunciation and origin of the word". Oxford Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- "definition: meaning, pronunciation and origin of the word". Oxford Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- "definition: meaning, pronunciation and origin of the word". Oxford Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- "Sevastopol", The Ukrainian Soviet Encyclopedia, UK: Leksika

- Севастополь (Sevastopol) (in Russian). Moscow: Great Soviet Encyclopedia.

- "Основание и развитие Севастополя (Osnovaniye i razvitiye Sevastopolya)" [Foundation and development of Sevastopol] (in Russian). Sevastopol.info. 28 May 2007. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- "Українське життя в Севастополi Михайло ЛУКІНЮК ОБЕРЕЖНО: МІФИ! Міф про юридичну належність Севастополя Росії". archive.org. Archived from the original on 8 December 2014.

- Kuzio, Taras (15 April 1998). Contemporary Ukraine. google.com. ISBN 9780765631503.

- "Статьи / газета Флот України: ПОЧТИ 50 ЛЕТ НАЗАД. СЕВАСТОПОЛЬ В 1955 ГОДУ". web.archive.org. 8 December 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- Secession as an International Phenomenon: From America's Civil War to Contemporary Separatist Movements edited by Don Harrison Doyle (page 284)

- Schmemann, Serge (10 July 1993), "Russian Parliament Votes a Claim to Russian Port of Sevastopol", The New York Times

- People, CN, 28 December 2005

- "Лужков знайшов у серці рану і хоче почувати себе в Криму як вдома". pravda.com.ua.

- "Calm sea in Sevastopol", Kyiv Post, 4 September 2009, archived from the original on 15 September 2008

- "Sevastopol authorities asking to raise compensation fees for Russian Black Sea Fleet's basing", Kyiv Post, 28 July 2009, archived from the original on 1 March 2012

- "Parliamentary chaos as Ukraine ratifies fleet deal", World, UK: BBC, 27 April 2010

- "Putin signs laws on reunification of Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol with Russia". ITAR TASS. 21 March 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- Kottek, M.; J. Grieser; C. Beck; B. Rudolf; F. Rubel (2006). "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated" (PDF). Meteorol. Z. 15 (3): 259–263. Bibcode:2006MetZe..15..259K. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- "The duration of sunshine in some cities of the former USSR" (in Russian). Meteoweb. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- "Sevastopol Climate Summary". pogodaiklimat.ru. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- "The City State Administration". Sevastopol City State Administration. Archived from the original on 11 February 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- "Ukraine: Sevastopol installs pro-Russian mayor as separatism fears grow". The Guardian. 25 February 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- "Sevastopol City Council refuses to recognize Kyiv leadership". Kyiv Post. 2 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- http://docs.sevsovet.com.ua/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=2482:№6-зс-от-30042014-г-о-порядке-избрания-губернатора-города-севастополя-депутатами-законодательного-собрания-города-севастополя&Itemid=226

- Stroitel, Tradekey.com See https://www.tradekey.com/company/Stroitel-1284650.html

- "Sevmorverf (Sevastopol Shipyard)". Federation of American Scientists. 24 August 2000. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- "population 2019-01-01" (PDF).

- "2001 Ukrainian census". Ukrcensus.gov.ua. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- "Balaklava Bayfront Plaza, Sevastopol". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- "В Харькове появится памятник Сагайдачному". Status Quo.

- Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 172. ISBN 3540002383.

External links

- Official website (in Russian) (Russian administration)

- Official website at the Wayback Machine (archive index) (Ukrainian administration)

- Satellite picture by Google Maps

- The murder of the Jews of Sevastopol during World War II, at Yad Vashem website.

Template:Cities in Russia