History of Crimea

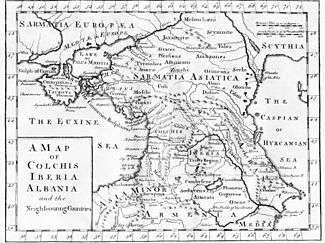

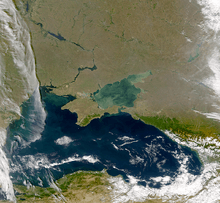

The recorded history of the Crimean Peninsula, historically known as Tauris (Greek: Ταυρική), Taurica, and the Tauric Chersonese (Greek: Χερσόνησος Ταυρική, "Tauric Peninsula"), begins around the 5th century BC when several Greek colonies were established along its coast. The southern coast remained Greek in culture for almost two thousand years as part of the Roman Empire (47 BC – 330 AD), and its successor states, the Byzantine Empire (330 AD – 1204 AD), the Empire of Trebizond (1204 AD – 1461 AD), and the independent Principality of Theodoro (ended 1475 AD). In the 13th century, some port cities were controlled by the Venetians and by the Genovese. The Crimean interior was much less stable, enduring a long series of conquests and invasions; by the early medieval period it had been settled by Scythians (Scytho-Cimmerians), Tauri, Greeks, Romans, Goths, Huns, Bulgars, Kipchaks and Khazars. In the medieval period, it was acquired partly by Kievan Rus', but fell to the Mongol invasions as part of the Golden Horde. They were followed by the Crimean Khanate and the Ottoman Empire, which conquered the coastal areas as well, in the 15th to 18th centuries.

In 1783, the Ottoman Empire was defeated by Catherine the Great. Crimea was traded to Russia by the Ottoman Empire as part of the Treaty provision. After two centuries of conflict, the Russian fleet had destroyed the Ottoman navy and the Russian army had inflicted heavy defeats on the Ottoman land forces. The ensuing Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca forced the Sublime Porte to recognize the Tatars of the Crimea as politically independent. Catherine the Great's incorporation of the Crimea in 1783 from the defeated Ottoman Empire into the Russian Empire increased Russia's power in the Black Sea area. The Crimea was the first Muslim territory to slip from the sultan's suzerainty. The Ottoman Empire's frontiers would gradually shrink for another two centuries, and Russia would proceed to push her frontier westwards to the Dniester.

In 1921 the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was created. This republic was dissolved in 1945, and the Crimea became an oblast first of the Russian SSR (1945–1954) and then the Ukrainian SSR (1954–1991). From 1991 the territory was covered by the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol City within independent Ukraine. However, during the 2014 Crimean crisis, the peninsula was taken over by Russia and a referendum on whether to rejoin Russia was held. Shortly after the result in favour of joining Russia was announced, Crimea was annexed by the Russian Federation as two federal subjects: the Republic of Crimea and the federal city of Sevastopol.

Prehistory

Archaeological evidence of human settlement in Crimea dates back to the Middle Paleolithic. Neanderthal remains found at Kiyik-Koba Cave have been dated to about 80,000 BP.[1] Late Neanderthal occupations have also been found at Starosele (c. 46,000 BP) and Buran Kaya III (c. 30,000 BP).[2]

Archaeologists have found some of the earliest anatomically modern human remains in Europe in the Buran-Kaya caves in the Crimean Mountains (east of Simferopol). The fossils are about 32,000 years old, with the artifacts linked to the Gravettian culture.[3][4] During the Last Glacial Maximum, along with the northern coast of the Black Sea in general, Crimea was an important refuge from which north-central Europe was re-populated after the end of the Ice Age. The East European Plain during this time was generally occupied by periglacial loess-steppe environments, although the climate was slightly warmer during several brief interstadials and began to warm significantly after the beginning of the Late Glacial Maximum. Human site occupation density was relatively high in the Crimean region and increased as early as ca. 16,000 years before the present.[5]

Proponents of the Black Sea deluge hypothesis believe Crimea did not become a peninsula until relatively recently, with the rising of the Black Sea level in the 6th millennium BC.

The beginning of the Neolithic in Crimea is not associated with agriculture, but instead with the beginning of pottery production, changes in flint tool-making technologies, and local domestication of pigs. The earliest evidence of domesticated wheat in the Crimean peninsula is from the Chalcolithic Ardych-Burun site, dating to the middle of the 4th millennium BC[6]

By the 3rd millennium BC, Crimea had been reached by the Yamna or "pit grave" culture, assumed to correspond to a late phase of Proto-Indo-European culture in the Kurgan hypothesis.

Antiquity

Tauri and Scythians

In the early Iron Age, Crimea was settled by two groups: the Tauri (or Scythotauri) in southern Crimea, and the East Iranian-speaking Scythians north of the Crimean Mountains.

Taurians intermixed with the Scythians starting from the end of 3rd century BC were mentioned as Tauroscythians and Scythotaurians in the works of ancient Greek writers.[7][8]

The origins of the Tauri, from which the classical name of Crimea as Taurica arose, are unclear. They are possibly a remnant of the Cimmerians displaced by the Scythians. Alternative theories relate them to the Abkhaz and Adyghe peoples, which at that time resided much farther west than today.

The Greeks, who eventually established colonies in Crimea during the Archaic Period, regarded the Tauri as a savage, warlike people. Even after centuries of Greek and Roman settlement, the Tauri were not pacified and continued to engage in piracy on the Black Sea.[9] By the 2nd century BC they had become subject-allies of the Scythian king Scilurus.[10]

The Crimean Peninsula north of the Crimean Mountains was occupied by Scythian tribes. Their center was the city of Scythian Neapolis on the outskirts of present-day Simferopol. The town ruled over a small kingdom covering the lands between the lower Dnieper River and northern Crimea. In the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, Scythian Neapolis was a city "with a mixed Scythian-Greek population, strong defensive walls and large public buildings constructed using the orders of Greek architecture".[11] The city was eventually destroyed in the mid-3rd century AD by the Goths.

Greek settlement

The ancient Greeks were the first to name the region Taurica after the Tauri. As the Tauri inhabited only mountainous regions of southern Crimea, at first the name Taurica was used only to this southern part, but later it was extended to name the whole peninsula.

.svg.png)

Greek city-states began establishing colonies along the Black Sea coast of Crimea in the 7th or 6th century BC.[12] Feodosiya and Panticapaeum were established by Milesians. In the 5th century BC, Dorians from Heraclea Pontica founded the sea port of Chersonesos (in modern Sevastopol).

In 438 BC, the Archon (ruler) of Panticapaeum assumed the title of the King of Cimmerian Bosporus, a state that maintained close relations with Athens, supplying the city with wheat, honey and other commodities. The last of that line of kings, Paerisades V, being hard-pressed by the Scythians, put himself under the protection of Mithridates VI, the king of Pontus, in 114 BC. After the death of this sovereign, his son, Pharnaces II, was invested by Pompey with the Kingdom of the Cimmerian Bosporus in 63 BC as a reward for the assistance rendered to the Romans in their war against his father. In 15 BC, it was once again restored to the king of Pontus, but from then ranked as a tributary state of Rome.

Roman Empire

_(12853680765).jpg)

In the 2nd century BC, the eastern part of Taurica became part of the Bosporan Kingdom, before being incorporated into the Roman Empire in the 1st century BC.

During the AD 1st, 2nd and 3rd centuries, Taurica was host to Roman legions and colonists in Charax, Crimea. The Charax colony was founded under Vespasian with the intention of protecting Chersonesos and other Bosporean trade emporiums from the Scythians. The Roman colony was protected by a vexillatio of the Legio I Italica; it also hosted a detachment of the Legio XI Claudia at the end of the 2nd century. The camp was abandoned by the Romans in the mid-3rd century. This de facto province would have been controlled by the legatus of one of the Legions stationed in Charax.

Throughout the later centuries, Crimea was invaded or occupied successively by the Goths (AD 250), the Huns (376), the Bulgars (4th–8th century), the Khazars (8th century).

Crimean Gothic, an East Germanic language, was spoken by the Crimean Goths in some isolated locations in Crimea until the late 18th century.[13]

Middle Ages

Rus' and Byzantium

In the mid-10th century, the eastern area of Crimea was conquered by Prince Sviatoslav I of Kiev and became part of the Kievan Rus' principality of Tmutarakan. In 988, Prince Vladimir I of Kiev also captured the Byzantine town of Chersonesos (presently part of Sevastopol) where he later converted to Christianity. An impressive Russian Orthodox cathedral marks the location of this historic event.

At the same time, the southern fringe of the peninsula was controlled by the Byzantine Empire as the Cherson theme.

Mongol invasion and later medieval period

Kiev lost its hold on the Crimean interior in the early 13th century due to the Mongol invasions. In the summer of 1238 Batu Khan devastated the Crimean peninsula and pacified Mordovia, reaching Kiev by 1240. The Crimean interior came under the control of the Turco-Mongol Golden Horde from 1239 to 1441. The name Crimea (via Italian, from Turkic Qirim) originates as the name of the provincial capital of the Golden Horde, the city now known as Staryi Krym.

The Byzantines and their successor states (the Empire of Trebizond (1204-1461) and the Principality of Theodoro (early 14th century–1475)) continued to maintain control over parts of southern Crimea until the Ottoman conquest in 1475. In the 13th century the Republic of Genoa seized the settlements which their rivals, the Venetians, had built along the Crimean coast and established themselves at Cembalo (present-day Balaklava), Soldaia (Sudak), Cherco (Kerch) and Caffa (Feodosiya), gaining control of the Crimean economy and the Black Sea commerce for two centuries.

In 1346 the Golden Horde army besieging Genoese Kaffa (present-day Feodosiya) catapulted the bodies of Mongol warriors who had died of plague over the walls of the city. Historians have speculated that Genoese refugees from this engagement may have brought the Black Death to Western Europe.[14]

Crimean Khanate (1441–1783)

After the destruction of the Mongol Golden Horde army by Timur (1399), the Crimean Tatars founded an independent Crimean Khanate under Hacı I Giray, a descendant of Genghis Khan, in 1441. Hacı I Giray and his successors reigned first at Qırq Yer, and from the beginning of the 15th century, at Bakhchisaray.[15]

The Crimean Tatars controlled the steppes that stretched from the Kuban and to the Dniester River, however, they were unable to take control over commercial Genoese towns. After the Crimean Tatars asked for help from the Ottomans, an Ottoman invasion of the Genoese towns led by Gedik Ahmed Pasha in 1475 brought Kaffa and the other trading towns under their control.[16]:78

After the capture of the Genoese towns, the Ottoman Sultan held Meñli I Giray captive,[17] later releasing him in return for accepting Ottoman suzerainty over the Crimean Khans and allowing them rule as tributary princes of the Ottoman Empire.[16]:78[18] However, the Crimean Khans still had a large amount of autonomy from the Ottoman Empire, and followed the rules they thought best for them.

Crimean Tatars introduced raids into Ukrainian lands, in which they captured slaves for on-sale.[16]:78 For example, from 1450 to 1586, eighty-six Tatar raids were recorded, and from 1600 to 1647, seventy.[16]:106 In the 1570s close to 20,000 slaves a year went on sale in Kaffa.[19]

Slaves and freedmen formed approximately 75% of the Crimean population.[20] In 1769 a last major Tatar raid, which took place during the Russo-Turkish War, saw the capture of 20,000 slaves.[21]

Tatar incursions

The Crimean Tatars as an ethnic group entered the Crimean Khanate during the 15th to 18th centuries. They are descended from a complicated mixture of Turkic peoples which settled in Crimea from the 8th century, presumably also absorbing remnants of the Crimean Goths and the Genoese. Linguistically, they are the related to the Khazars, who invaded the Crimea in the mid 8th century, their language forming part of the Kipchak or Northwestern branch of the Turkic languages, although it shows substantial Oghuz influence due to historical Ottoman Turkish presence in the Crimea.

A small enclave of the Crimean Karaites, a people of Jewish descent practising Karaism who later adopted a Turkic language, formed in the 13th century. It existed among the Muslim Crimean Tatars, primarily in the mountainous Çufut Qale area.

Cossack incursions

In 1553–1554 Cossack Hetman Dmytro Vyshnevetsky gathered together groups of Cossacks and constructed a fort designed to obstruct Tatar raids into Ukraine. With this action, he founded the Zaporozhian Sich, with which he would launch a series of attacks on the Crimean Peninsula and the Ottoman Turks.[16]:109 In 1774 the Crimean Khans fell under Russian influence with the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca.[16]:176 In 1778 the Russian government deported numerous Greek Orthodox residents from Crimea to the vicinity of Mariupol.[22] In 1783 the Russian Empire annexed all of Crimea.[16]:176

Russian Empire (1783–1917)

The Taurida Oblast was created by a decree of Catherine the Great on 2 February 1784. The center of the oblast was first in Karasubazar but was moved to Simferopol later in 1784. The establishment decree divided the oblast into 7 uyezds. However, by a decree of Paul I on 12 December 1796, the oblast was abolished and the territory, divided into 2 uyezds (Akmechetsky [Акмечетский] and Perekopsky [Перекопский]) was attached to the second incarnation of the Novorossiysk Governorate.

After 1799, the territory was divided into uyezds. At that time, there were 1,400 inhabited villages and 7 towns—Simferopol, Sevastopol, Yalta, Yevpatoria, Alushta, Feodosiya, and Kerch.

In 1802, in the course of Paul I's administrative reform of areas that were annexed from the Crimean Khanate, the Novorossiysk Governorate was again abolished and subdivided. Crimea was attached to a new Taurida Governorate established with its centre at Simferopol. The governorate included both the 25,133 km2 Crimea as well as 38,405 km2 of adjacent areas of the mainland. In 1826 Adam Mickiewicz published his seminal work The Crimean Sonnets after traveling through the Black Sea Coast.

By the late 19th century, Crimean Tatars continued to form a slight plurality of Crimea's still largely rural population but there were large numbers of Russians and Ukrainians as well as smaller numbers of Germans, Jews (including Krymchaks and Crimean Karaites), Bulgarians, Belarusians, Turks, Armenians, and Greeks and Gypsies.

The Tatars were the predominant portion of the population in the mountainous area and about half of the steppe population. Russians were concentrated most heavily in Feodosiya district. Germans and Bulgarians settled in the Crimea at the beginning of the 19th century, receiving a large allotment and fertile land and later wealthy colonists began to buy land, mainly in Perekopsky and Evpatoria uyezds.

Crimean War

The Crimean War (1853–1856), a conflict fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the French Empire, the British Empire, the Ottoman Empire, the Kingdom of Sardinia, and the Duchy of Nassau, was part of a long-running contest between the major European powers for influence over territories of the declining Ottoman Empire. Russia and the Ottoman Empire went to war in October 1853 over Russia's rights to protect Orthodox Christians; to stop Russia's conquests France and Britain entered in March 1854. While some of the war was fought elsewhere, the principal engagements were in Crimea.

Following action in the Danubian Principalities and in the Black Sea, allied troops landed in Crimea in September 1854 and besieged the city of Sevastopol, home of the Tsar's Black Sea Fleet and the associated threat of potential Russian penetration into the Mediterranean. After extensive fighting throughout Crimea, the city fell on 9 September 1855.

The war devastated much of the economic and social infrastructure of Crimea. The Crimean Tatars had to flee from their homeland en masse, forced by the conditions created by the war, persecution and land expropriations. Those who survived the trip, famine and disease, resettled in Dobruja, Anatolia, and other parts of the Ottoman Empire. Finally, the Russian government decided to stop the process, as the agriculture began to suffer due to the unattended fertile farmland.

Potemkin sunk a submarine

In 1909, the Russian battleship Potemkin accidentally sank a Russian submarine.

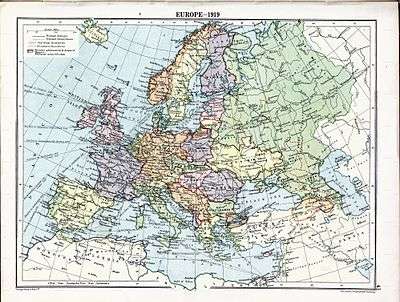

Russian Civil War (1917–1921)

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, the military and political situation in Crimea was chaotic like that in much of Russia. During the ensuing Russian Civil War, Crimea changed hands numerous times and was for a time a stronghold of the anti-Bolshevik White Army. It was in Crimea that the White Russians led by General Wrangel made their last stand against Nestor Makhno and the Red Army in 1920. When resistance was crushed, many of the anti-Bolshevik fighters and civilians escaped by ship to Istanbul.

Approximately 50,000 White prisoners of war and civilians were summarily executed by shooting or hanging after the defeat of General Wrangel at the end of 1920.[23] This is considered one of the largest massacres in the Civil War.[24]

Crimea changed hands several times over the course of the conflict and several political entities were set up on the peninsula. These included:

- Crimean People's Republic—December 1917–January 1918—Crimean Tatar government

- Taurida Soviet Socialist Republic—19 March 1918 – 30 April 1918—Bolshevik government

- Ukrainian People's Republic —May 1918–June 1918

- First Crimean Regional Government—25 June 1918 – 25 November 1918—German puppet state under Lipka Tatar General Maciej (Suleyman) Sulkiewicz

- Second Crimean Regional Government—November 1918–April 1919—Anti-Bolshevik government under Crimean Karaite former Kadet member Solomon Krym

- Crimean Socialist Soviet Republic—2 April 1919–June 1919—Bolshevik government

- South Russian Government—February 1920–April 1920—Government of White movement's General Anton Denikin

- Government of South Russia—April 1920 (officially, 16 August 1920)–16 November 1920—Government of White movement's General Pyotr Wrangel

- Bolshevik Revolutionary committee government—November 1920–18 October 1921—Bolshevik government under Béla Kun (until 20 February 1921), then Mikhail Poliakov

- Crimean Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic—18 October 1921 – 30 June 1945—Autonomous republic of the RSFSR in the Soviet Union

Soviet Union (1921–1991)

Interbellum

On 18 October 1921, the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was created as part of the Russian SFSR which, in turn, became part of the new Soviet Union.[18] However, this did not protect the Crimean Tatars, who constituted about 25% of the Crimean population,[25] from Joseph Stalin's repressions of the 1930s.[18] The Greeks were another cultural group that suffered. Their lands were lost during the process of collectivisation, in which farmers were not compensated with wages. Schools which taught Greek were closed and Greek literature was destroyed, because the Soviets considered the Greeks as "counter-revolutionary" with their links to capitalist state Greece, and their independent culture.[18]

From 1923 until 1944 there was an effort to create Jewish settlements in Crimea. At one time, Vyacheslav Molotov suggested the idea of establishing a Jewish homeland.[26]

Crimea experienced two severe famines in the 20th century, the Famine of 1921–1922 and the Holodomor of 1932–1933.[27] A large Slavic population influx occurred in the 1930s as a result of the Soviet policy of regional development. These demographic changes permanently altered the ethnic balance in the region.

World War II

During World War II, Crimea was a scene of some of the bloodiest battles. The leaders of the Third Reich were anxious to conquer and colonize the fertile and beautiful peninsula as part of their policy of resettling the Germans in Eastern Europe at the expense of the Slavs. The Germans suffered heavy casualties in the summer of 1941 as they tried to advance through the narrow Isthmus of Perekop linking Crimea to the Soviet mainland. Once the German army broke through (Operation Trappenjagd), they occupied most of Crimea, with the exception of the city of Sevastopol, which was later awarded the honorary title of Hero City after the war. The Red Army lost over 170,000 men killed or taken prisoner, and three armies (44th, 47th, and 51st) with twenty-one divisions.[28]

_(B%26W).jpg)

Sevastopol held out from October 1941 until 4 July 1942 when the Germans finally captured the city. From 1 September 1942, the peninsula was administered as the Generalbezirk Krim (general district of Crimea) und Teilbezirk (and sub-district) Taurien by the Nazi Generalkommissar Alfred Eduard Frauenfeld (1898–1977), under the authority of the three consecutive Reichskommissare for the entire Ukraine. In spite of heavy-handed tactics by the Nazis and the assistance of the Romanian and Italian troops, the Crimean mountains remained an unconquered stronghold of the native resistance (the partisans) until the day when the peninsula was freed from the occupying force.

The Crimean Jews were targeted for annihilation during Nazi occupation. According to Yitzhak Arad, "In January 1942 a company of Tatar volunteers was established in Simferopol under the command of Einsatzgruppe 11. This company participated in anti-Jewish manhunts and murder actions in the rural regions."[29]

In 1944, Sevastopol came under the control of troops from the Soviet Union. The so-called "City of Russian Glory" once known for its beautiful architecture was entirely destroyed and had to be rebuilt stone by stone. Due to its enormous historical and symbolic meaning for the Russians, it became a priority for Stalin and the Soviet government to have it restored to its former glory within the shortest time possible.[30]

Deportation of Crimean Tatars

On 18 May 1944, the entire population of the Crimean Tatars were forcibly deported in the "Sürgün" (Crimean Tatar for exile) to Central Asia by Joseph Stalin's Soviet government as a form of collective punishment on the grounds that they allegedly had collaborated with the Nazi occupation forces and formed pro-German Tatar Legions.[16]:483 On 26 June of the same year Armenian, Bulgarian and Greek population was also deported to Central Asia, and partially to Ufa and its surroundings in the Ural mountains. By the end of summer 1944, the ethnic cleansing of Crimea was complete. In 1967, the Crimean Tatars were rehabilitated, but they were banned from legally returning to their homeland until the last days of the Soviet Union. The Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was abolished on 30 June 1945 and transformed into the Crimean Oblast (province) of the Russian SFSR.

1954 Transfer to Ukraine

On 19 February 1954, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR issued a decree on the transfer of the Crimean region of the RSFSR to the Ukrainian SSR.[31] This Supreme Soviet Decree states that this transfer was motivated by "the commonality of the economy, the proximity, and close economic and cultural relations between the Crimean region and the Ukrainian SSR".[32]

In post-war years, Crimea thrived as a tourist destination, with new attractions and sanatoriums for tourists. Tourists came from all around the Soviet Union and neighbouring countries, particularly from the German Democratic Republic.[18] In time the peninsula also became a major tourist destination for cruises originating in Greece and Turkey. Crimea's infrastructure and manufacturing also developed, particularly around the sea ports at Kerch and Sevastopol and in the oblast's landlocked capital, Simferopol. Populations of Ukrainians and Russians alike doubled, with more than 1.6 million Russians and 626,000 Ukrainians living on the peninsula by 1989.[18]

The North Crimean Canal (Russian: Северо-Крымский канал, Ukrainian: Північно-Кримський канал; in the Soviet Union – North Crimean Canal of the Lenin's Komsomol of Ukraine) is a land improvement canal for irrigation and watering of Kherson Oblast in southern Ukraine, and the Crimean peninsula. The canal also has multiple branches throughout Kherson Oblast and the Crimean peninsula.

The construction preparation started in 1957 soon after the transfer of Crimea of 1954. The main project works took place between 1961 and 1971 and had three stages. The construction was conducted by the Komosomol members sent by the Komsomol travel ticket (Komsomolskaya putyovka) as part of shock construction projects and accounted for some 10,000 "volunteer" workers.

Autonomous Republic within Ukraine (1991–2014)

.jpg)

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, Crimea became part of the newly independent Ukraine. Independence was supported by a referendum in all regions of Ukrainian SSR, including Crimea.[33] 54% of the Crimean voters supported independence with a 60% turnout (in Sevastopol 57% supported independence).[34] The percentage of the total Crimean electorate that had voted for Ukrainian independence in the referendum was 37%.[35] In 1994, the legal status of Crimea as part of Ukraine was backed up by Russia, who pledged to uphold the territorial integrity of Ukraine in a memorandum signed in 1994, also signed by the US and UK.[36][37]

This new situation led to tensions between Russia and Ukraine. With the Black Sea Fleet based on the peninsula, worries of armed skirmishes were occasionally raised. In August 1991, Yuriy Meshkov established the Republican Movement of Crimea which was registered on 19 November.[36]

On 2 September 1991, the National Movement of Crimean Tatars appealed to the V Extraordinary Congress of People's Deputies in Russia demanding the program how to return the deported Tatar population back to Crimea. Based on the resolution of the Verkhovna Rada (the Crimean parliament) on 26 February 1992, the Crimean ASSR was renamed the Republic of Crimea.[38] The Crimean parliament proclaimed self-government on 5 May 1992.[39][38] (which was yet to be approved by a referendum to be held 2 August 1992[40]) and passed the first Crimean constitution the same day.[40] On 6 May 1992 the same parliament inserted a new sentence into this constitution that declared that Crimea was part of Ukraine.[40]

On 19 May, Crimea agreed to remain as part of Ukraine and annulled their proclamation of self-government. By 30 June, Crimean Communists forced the Kiev government to expand on the already extensive autonomous status of Crimea.[16]:587 In the same period, Russian president Boris Yeltsin and Ukraine's Leonid Kravchuk agreed to divide the former Soviet Black Sea Fleet between Russia and the newly formed Ukrainian Navy.[41] On 24 October, Meshkov re-registered his movement as the Republican Party of Crimea – Party of the Republican Movement of Crimea. On 11 December 1992, the President of Ukraine called the attempt of "the Russian deputies to charge the Russian parliament with a task to define the status of Sevastopol as an imperial disease".[42] On 17 December 1992, the office of the Ukrainian presidential representative in Crimea was created, which caused wave of protests a month later. Among the protesters that created the unsanctioned rally were the Sevastopol branches of the National Salvation Front, the Russian Popular Assembly, and the All-Crimean Movement of the Voters for the Republic of Crimea. The protest was held in Sevastopol on 10 January at Nakhimov Square.

On 15 January 1993, Kravchuk and Yeltsin in the meeting in Moscow appointed Eduard Baltin as the commander of the Black Sea Fleet. At the same time the Union of the Ukrainian Naval Officers protested the Russian intervention into the Ukrainian internal affairs. Soon after that there were more anti-Ukrainian protests led by the Meshkov's party, the Voters for the Crimean Republic, Yedinstvo, and the Union of Communists that demanded to turn Sevastopol under the Russian jurisdiction and followed by the interview given by the Sevastopol's Communist, Vasyl Parkhomenko, who said that the city's Communists request to recognize the Russian as the state language and restoration of the Soviet Union. On 19 March 1993, the Crimean deputy and the member of the National Salvation Front, Alexander Kruglov, threatened the members of the Crimean Ukrainian Congress not allow into the building of the Republican Council. A couple of days after that, Russia established an information center in Sevastopol. In April 1993, the Ukrainian Ministry of Defence submitted an appeal to Verkhovna Rada to suspend the Yalta Agreement of 1992 that divided the Black Sea Fleet that was followed by the request from the Ukrainian Republican Party to recognize the Fleet either fully Ukrainian or a fleet of a foreign country in Ukraine. Also over 300 Russian legislators called the planned Congress of Ukrainian Residents a political provocation.

On 14 April 1993, the Presidium of the Crimean parliament called for the creation of the presidential post of the Crimean Republic. A week later the Russian deputy, Valentin Agafonov, stated that Russia is ready to supervise the referendum on Crimean independence and include the republic as a separate entity in the CIS. On 28 July 1993, one of the leaders of the Russian Society of Crimea, Viktor Prusakov, stated that his organization is ready for an armed mutiny and establishment of the Russian administration in Sevastopol. In September, Eduard Baltin accused Ukraine of converting some of his fleet and conducting an armed assault on his personnel, and threatened to take countermeasures of placing the fleet on alert.

On 14 October 1993, the Crimean parliament established the post of President of Crimea and agreed on the quota of the Crimean Tatars representation in the Council to 14. The head of the Russian People's Council in Sevastopol, Alexander Kruglov, called it excessive. The chairman of the Tatar Mejlis, Mustafa Abdülcemil Qırımoğlu, used words "categorically against" in regards to the proposed election for Crimean president on 16 January. He stated that there cannot be two presidents in a single state. On 6 November, the Crimean Tatar leader, Yuriy Osmanov was murdered. A series of terrorist actions rocked the peninsula in the winter; among them were the arson of the Mejlis apartment, the shooting of a Ukrainian official, several hooligan attacks on Meshkov, the bomb explosion in the house of a local parliamentary, the assassination attempt on a Communist presidential candidate, and others. On 2 January 1994, the Mejlis announced a boycott of the presidential elections, which were later canceled. The boycott itself was later taken on by other Crimean Tatar organizations. On 11 January, the Mejlis announced their representative, Mykola Bahrov, the speaker of the Crimean parliament, as the presidential candidate. On 12 January, some other candidates accused Bahrov of severe methods of agitation. At the same time, Vladimir Zhirinovsky called on the people of Crimea to vote for the Russian Sergei Shuvainikov.

On 30 January 1994, the pro-Russian Yuriy Meshkov was elected to the new post but quickly ran into conflicts with parliament. On 8 September, the Crimean parliament degraded the President's powers from the head of state to the head of the executive power only, to which Meshkov responded by disbanding parliament and announcing his control over Crimea four days later. On 17 March 1995, the parliament of Ukraine intervened, scrapping the Crimean Constitution and removing Meshkov along with his office for his actions against the state and promoting integration with Russia.[43] Meshkov was removed from power after Ukrainian special forces had entered his residence, disarmed his bodyguards and put him on a plane to Moscow (Russia).[44] After an interim constitution lasting from 4 April 1996 to 23 December 1998, the current constitution was put into effect, changing the territory's name to the Autonomous Republic of Crimea.

Following the ratification of the May 1997 Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, and Partnership on friendship and division of the Black Sea Fleet, international tensions slowly eased off. With the treaty, Moscow recognized Ukraine's borders and territorial integrity, and accepted Ukraine's sovereignty over Crimea and Sevastopol.[16]:600 In a separate agreement, Russia was to receive 80 percent of the Black Sea Fleet and use of the military facilities in Sevastopol on a 20-year lease.[16]:600

However, other controversies between Ukraine and Russia still remain, including the ownership of a lighthouse on Cape Sarych. Because the Russian Navy controlled 77 geographical objects on the south Crimean Shore, the Sevastopol Government Court ordered the vacating of the objects, which the Russian military did not carry out.[45] Since August 3, 2005, the lighthouse has been controlled by the Russian Army.[46] Through the years, there have been various attempts to return Cape Sarych to Ukrainian territory, all of which were unsuccessful.

In 2006, protests broke out on the peninsula after U.S. Marines[47] arrived at the Crimean city of Feodosiya to take part in the Sea Breeze 2006 Ukraine-NATO military exercise. Protesters greeted the marines with barricades and slogans bearing "Occupiers go home!" and a couple of days later, the Crimean parliament declared Crimea a "NATO-free territory." After several days of protest, the U.S. Marines withdrew from the peninsula.[48]

In September 2008, the Ukrainian Foreign Minister Volodymyr Ohryzko accused Russia of giving out Russian passports to the population in the Crimea and described it as a "real problem" given Russia's declared policy of military intervention abroad to protect Russian citizens.[49]

During a press conference in Moscow on 16 February 2009, the Mayor of Sevastopol Serhiy Kunitsyn claimed (citing recent polls) that the population of Crimea is opposed to the idea of becoming a part of Russia.[50]

Although western newspapers like the Wall Street Journal have speculated about a Russian coup in Sevastopol or another Crimean city in connection with the Russian-Georgian war and the Recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia by Russia.[51] Valentyn Nalyvaychenko, acting head of the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU), stated on 17 February 2009, that he is confident that any "Ossetian scenario" is impossible in Crimea.[52] The SBU had started criminal proceedings against the pro-Russian association "People's front Sevastopol-Crimea-Russia" in January 2009.[53]

On the 55th anniversary of the transfer of the Crimea from the Russian SFSR to the Ukrainian SSR (on 19 February 2009) some 300 to 500 people took part in rallies to protest against the transfer.[54][55]

On 24 August 2009, anti-Ukrainian demonstrations were held in Crimea by ethnic Russian residents. Sergei Tsekov (of the Russian Bloc[56] and then deputy speaker of the Crimean parliament[57]) said then that he hoped that Russia would treat the Crimea the same way as it had treated South Ossetia and Abkhazia.[58]

Chaos in the Verkhovna Rada (the Ukrainian parliament) during a debate over the extension of the lease on a Russian naval base erupted on 27 April 2010 after Ukraine's parliament ratified the treaty that extends Russia’s lease on a military wharf and shore installations in the Crimean port Sevastopol until 2042. The Chairman of the Verkhovna Rada Volodymyr Lytvyn had to be shielded by umbrellas as he was pelted with eggs, while smoke bombs exploded and politicians brawled.[59][60] Along with the Verkhovna Rada the treaty was ratified by the Russian State Duma as well.[61]

Before 2014, Crimea can be considered a part of the political base of then President Viktor Yanukovych. Thus, in the period just prior to 2014, Crimea was not experiencing intense mobilization against Ukraine or on behalf of absorption into Russia.[62]

Russian annexation and aftermath (2014–present)

The crisis unfolded in late February 2014 in the aftermath of the Euromaidan revolution. On 21 February, President Viktor Yanukovych agreed to a three-party memorandum that would have kept him in office until the end of the year. Within 24 hours the agreement was broken by the Maidan-activists and the president was forced to flee. He was dismissed the following day by a rump Verkhovna Rada, the legislature elected in 2012, and the Government he dismissed was replaced by a non-elected, illegal "Government", contrary to the Constitution. In the absence of a president, the newly appointed Speaker of the legislature, Oleksandr Turchynov, became acting President with limited powers. Russia labeled events as a "coup d'état" and later began referring to the government in Kyiv as a "junta," because armed extremists were involved in running the country and the legislature elected in 2012 was not still in charge. An election to elect a new president without opposition candidates was immediately set for 25 May.

Within days, on 26 February 2014, hundreds of pro-Russia and pro-Ukraine protesters clashed in front of the parliament building in Simferopol. The previous day, 300–500 pro-Russia protesters chanting "Russia" had replaced the flag of Ukraine with the flag of the Russian Federation.[63] Leaders of Crimean Tatars organised a meeting in order to block a meeting of Crimean parliament which is "doing everything to execute plans of separation of Crimea from Ukraine".[64][65] According to the Russian state media, the pretext of the clash was the purported abolition, on 23 February 2014, of a controversial law on the status of regional languages.

On 27 February, unidentified troops widely suspected of being Russian special forces seized the building of the Supreme Council of Crimea and the building of the Council of Ministers in Simferopol.[66][67] Whilst the "little green men" were occupying the Crimean parliament building, the parliament held an emergency session.[68][69] It voted to terminate the Crimean government, and replace Prime Minister Anatolii Mohyliov with Sergey Aksyonov.[70] According to the Constitution of Ukraine, the Prime Minister of Crimea is appointed by the Supreme Council of Crimea in consultation with the President of Ukraine.[71][72] Both Aksyonov and speaker Vladimir Konstantinov stated that they viewed Viktor Yanukovych as the de jure president of Ukraine, through whom they were able to ask Russia for assistance.[73]

The "little green men" began to surround Ukrainian bases in the peninsula and soon individuals were kidnapped. On 11 March, after disagreements between Crimea, Sevastopol, and the interim Government in Ukraine, the Crimean parliament and the city council of Sevastopol adopted a resolution to show their intention to unilaterally declare themselves independent as a single united nation with the possibility of joining the Russian Federation as a federal subject, should voters approve to do so in an upcoming referendum.

On 16 March, Crimea's government claimed that nearly 96% of those who voted in Crimea supported joining Russia. The vote received no international recognition and, aside from Russia, no country had sent official observers there.

On 17 March, the Crimean parliament officially declared its independence from Ukraine and requested to join the Russian Federation.

On 18 March 2014, the self-proclaimed independent Republic of Crimea signed a treaty of accession to the Russian Federation. The accession was granted but separately for each the former regions that composed it: one accession for the Autonomous Republic of Crimea as the Republic of Crimea— the same name as the short-lived self-proclaimed independent republic - and another accession for Sevastopol as a federal city. The accession was only recognised internationally by a few states with most regarding the action as illegal. Though Ukraine refused to accept the annexation, the Ukrainian military began to withdraw from Crimea on March 19.[74]

All actions of Crimean parliament were declared null and void by Ukrainian constitutional court that led to its disbandment by Ukrainian parliament.

The Ukrainian parliament has stated that the referendum is unconstitutional. The United States and the European Union said they consider the vote to be illegal, and warned that there may be repercussions for the Crimean ballot.

On 27 March, the U.N. General Assembly passed a non-binding resolution 100 in favour, 11 against and 58 abstentions in the 193-nation assembly that declared invalid Crimea's Moscow-backed referendum.[75][76][77][78][79]

On 31 March 2014, the Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev announced a series of programmes aimed at swiftly incorporating the territory of Crimea into Russia's economy and infrastructure. Medvedev announced the creation of a new ministry for Crimean affairs, and ordered Russia's top ministers who joined him there to make coming up with a development plan their top priority.[80] On 3 April 2014, the Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol became parts of Russia's Southern Military District.[81] On 11 April 2014, the Republic's parliament approved the new Constitution of the Republic of Crimea which came into legal effect the following day.[82] On 1 June 2014 Crimea officially switched over to the Russian ruble as its only form of legal tender.[83] On May 7, 2015 Crimea switched its phone codes (Ukrainian number system) to the Russian number system.[84]

In July 2015, Russian Prime Minister, Dmitry Medvedev, declared that Crimea had been fully integrated into Russia.[85]

On 18 September 2016, the whole of Crimea participated in the Russian legislative election.

Notes

- Trinkaus, Erik; Blaine Maley and Alexandra P. Buzhilova; Buzhilova, Alexandra P. (2008). "Brief Communication: Paleopathology of the Kiik-Koba 1 Neandertal". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 137 (1): 106–112. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20833. PMID 18357583.

- Hardy, Bruce; Marvin Kay; Anthony E. Marks; Katherine Monigal (2001). "Stone tool function at the paleolithic sites of Starosele and Buran Kaya III, Crimea: Behavioral implications". PNAS. 98 (19): 10972–10977. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9810972H. doi:10.1073/pnas.191384498. PMC 58583. PMID 11535837.

- Prat, Sandrine; Péan, Stéphane C.; Crépin, Laurent; Drucker, Dorothée G.; Puaud, Simon J.; Valladas, Hélène; Lázničková-Galetová, Martina; van der Plicht, Johannes; et al. (17 June 2011). "The Oldest Anatomically Modern Humans from Far Southeast Europe: Direct Dating, Culture and Behavior". plosone. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020834.

- Carpenter, Jennifer (20 June 2011). "Early human fossils unearthed in Ukraine". BBC. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- Hoffecker, John F. (2002). Desolate Landscapes: Ice-Age Settlement in Eastern Europe. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0813529929.

- Motuzaite-Matuzeviciute, Giedre; Sergey Telizhenko and Martin K. Jones; Jones, Martin K (2013). "The earliest evidence of domesticated wheat in the Crimea at Chalcolithic Ardych-Burun". Journal of Field Archaeology. 38 (2): 120–128. doi:10.1179/0093469013Z.00000000042.

- "The Taurians - Ancient period - Outlying areas - About Chersonesos". www.chersonesos.org. Retrieved 2019-02-06.

- "Taurians". www.encyclopediaofukraine.com. Retrieved 2019-02-06.

- Minns, Ellis Hovell (1913). Scythians and Greeks: A Survey of Ancient History and Archaeology on the North Coast of the Euxine from the Danube to the Caucasus. Cambridge University Press.

- "Tauri". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- Tsetskhladze, Gocha R, ed. (2001). North Pontic Archaeology. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 167. ISBN 978-90-04-12041-9.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière Hammond (1959). A history of Greece to 322 B.C. Clarendon Press. p. 109. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- Todd B. Krause and Jonathan Slocum. "The Corpus of Crimean Gothic". University of Texas at Austin. Archived from the original on 2007-03-02.

- Wheelis M. (2002). "Biological warfare at the 1346 siege of Caffa". Emerg Infect Dis. 8 (9): 971–5. doi:10.3201/eid0809.010536. PMC 2732530. PMID 12194776.

- The Tatar Khanate of Crimea Archived March 23, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Subtelny, Orest (2000). Ukraine: A History. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-8390-6.

- Mike Bennighof, Ph.D "Soldier Khan" Avalanche Press. April 2014.

- "History". blacksea-crimea.com. Archived from the original on April 4, 2007. Retrieved March 28, 2007.

- Halil Inalcik. "Servile Labor in the Ottoman Empire" in A. Ascher, B. K. Kiraly, and T. Halasi-Kun (eds), The Mutual Effects of the Islamic and Judeo-Christian Worlds: The East European Pattern, Brooklyn College, 1979, pp. 25–43.

- Slavery. Encyclopædia Britannica's Guide to Black History.

- Mikhail Kizilov. "Slave Trade in the Early Modern Crimea From the Perspective of Christian, Muslim, and Jewish Sources". Oxford University. 11 (1): 2–7.

- Вадим Джувага "Одна з перших депортацій імперії. Як кримськими греками заселили Дике Поле". Історична правда. 17 February 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2011. (in Ukrainian)

- Gellately, Robert (2007). Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe. Knopf. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-4000-4005-6.

- Nicolas Werth, Karel Bartosek, Jean-Louis Panne, Jean-Louis Margolin, Andrzej Paczkowski, Stephane Courtois, Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression, Harvard University Press, 1999, hardcover, page 100, ISBN 0-674-07608-7. Chapter 4: The Red Terror

- "Crimea: Introduction". The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th ed. Copyright © 2012, Columbia University Press. All rights reserved.

- Jeffrey Veidlinger, Before Crimea Was an Ethnic Russian Stronghold, It Was a Potential Jewish Homeland, UCSJ, 7 March 2014

- "Famine in Crimea, 1931". International Committee for Crimea.

- John Erickson (1975). The Road to Stalingrad: Stalin's War with Germany.

- Yitzhak Arad (2009). "The Holocaust in the Soviet Union". U of Nebraska Press, p.211, ISBN 080322270X

- M. Clement Hall (March 2014). The Crimea. A Very Short History. Lulu.com. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-304-97576-8.

- "Ukraine and the west: hot air and hypocrisy". The Guardian. March 10, 2014.

- "The Transfer of Crimea to Ukraine". International Committee for Crimea. July 2005. Retrieved March 25, 2007.

- Nationalist Mobilization and the Collapse of the Soviet State by Mark R. Beissinger, Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0-521-00148-9 (page 197)

- Russians in the Former Soviet Republics by Pål Kolstø, Indiana University Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0-253-32917-2 (page 191)

Ukraine and Russia:Representations of the Past by Serhii Plokhy, University of Toronto Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-8020-9327-1 (page 184) - Ukrainian Nationalism in the 1990s: A Minority Faith by Andrew Wilson, Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 0521574579 (page 129)

- Crimea and the Black Sea Fleet in Russian- Ukrainian Relations, Paper by Victor Zaborsky, September 1995

- What is so dangerous about Crimea?, bbc, 27 February 2014

- Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia 2004, Routledge, 2003, ISBN 1857431871 (page 540)

- Wolczuk, Kataryna (8 September 2010). "Catching up with 'Europe'? Constitutional Debates on the Territorial-Administrative Model in Independent Ukraine". Regional & Federal Studies. 12 (2): 65–88. doi:10.1080/714004750.

Wydra, Doris (11 November 2004). "The Crimea Conundrum: The Tug of War Between Russia and Ukraine on the Questions of Autonomy and Self-Determination". International Journal on Minority and Group Rights. 10 (2): 111–130. doi:10.1163/157181104322784826. - Russians in the Former Soviet Republics by Pål Kolstø, Indiana University Press, 1995, ISBN 0253329175 (page 194)

- Ready To Cast Off, TIME Magazine, June 15, 1992

- M.Drohobycky, xxxi

- Laws of Ukraine. Verkhovna Rada law No. 93/95-вр: On the termination of the Constitution and some laws of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea. Adopted on 1995-03-17. (Ukrainian)

- ""Crimea should be Ukrainian, but without bloodshed." How Ukraine saved the peninsula 25 years ago". LB.ua (in Ukrainian). 16 July 2020.

- "Access to Ukrainians is prohibited". Zakryta Zona (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on March 10, 2007. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- "The owner of the "sarych" lighthouse came back with a blank document to the President of Ukraine". CPCFPU (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- Page, Jeremy (June 8, 2006). "Anti-Nato protests threaten eastward expansion". The Times Online. London. Retrieved March 25, 2007.

- "Tensions rise in Crimea over NATO". EuroNews. 7 June 2006. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved March 25, 2007.

- Cheney urges divided Ukraine to unite against Russia 'threat Archived May 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Associated Press. September 6, 2008.

- Crimean population opposed to becoming part of Russia, UNIAN (16 February 2009)

- Russia's Next Target Could Be Ukraine by Leon Aron, Wall Street Journal, September 10, 2008

- Ossetian scenario impossible in Crimea – Nalyvaychenko, UNIAN, (February 17, 2009)

- Security Service of Ukraine institutes criminal proceedings against association "People's front" Sevastopol-Crimea-Russia" Archived February 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Radio Ukraine (January 29, 2009)

- Protestors in Crimea threw eggs at Khrushchev's portrait, RIA Novosti, (February 19, 2009)

- Events by themes: Torch procession on occasion of 55th anniversary of Crimea to Ukraine passing, UNIAN photo service, (February 19, 2009)

- , ()

- , ()

- "Russia and Ukraine in Intensifying Standoff". The New York Times. 28 August 2009.

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/8645847.stm Parliamentary chaos as Ukraine ratifies fleet deal. Page last updated at 08:46 GMT, Tuesday, 27 April 2010 09:46 UK. BBC World

- Vladimir Radyuhin. "Russia, Ukraine ratify base deal". The Hindu. (Kiev, Ukraine). 27 April 2010.

- Update: Ukraine, Russia ratify Black Sea naval lease, Kyiv Post (April 27, 2010)

- Ukrainian Crimea in The Crimean Archipelago: A Multimedia Dossier

- "Protesters set a flag of Russia on the building of Crimean Parliament".

- "Parliament of ARC is doing everything possible to separate Crimea from Ukraine, Chubarov said". Archived from the original on 2015-06-21.

- "Crimean Parliament doesn't raise a question of separation from Ukraine, speaker said".

- Andrew Higgins; Steven Erlanger (27 February 2014). "Gunmen Seize Government Buildings in Crimea". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- "Lessons identified in Crimea – does Estonia's national defence model meet our needs?". Estonian World. 5 May 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- Number of Crimean deputies present at referendum resolution vote unclear. Interfax-Ukraine, 27 February 2014.

- RPT-INSIGHT: How the separatists delivered Crimea to Moscow. Reuters, 13 March 2014.

- Crimea sets date for autonomy vote amid gunmen, anti-Kiev protests, (27 February 2014).

- Crimean parliament to decide on appointment of autonomous republic's premier on Tuesday, Interfax Ukraine (7 November 2011).

- (in Ukrainian) The new prime minister is the leader of Russian Unity, Ukrayinska Pravda (27 February 2014).

- Крымские власти объявили о подчинении Януковичу. lenta.ru (in Russian). 28 February 2014.

- Carol Morello and Kathy Lally (19 March 2014). "Ukraine says it is preparing to leave Crimea". The Washington Post.

- CHARBONNEAU AND DONATH, MIRJAM AND LOUIS (March 27, 2014). "U.N. General Assembly declares Crimea secession vote invalid". Reuters.

- Felton and Gumuchian, Marie-Louise and Alex (March 27, 2014). "U.N. General Assembly resolution calls Crimean referendum invalid". CNN.

- "Backing Ukraine's territorial integrity, UN Assembly declares Crimea referendum invalid". UN News Center. 27 March 2014.

- "UN General Assembly approves referendum calling Russia annexation of Crimea illegal". Associated Press. March 27, 2014.

- "Ukraine: UN condemns Crimea vote as IMF and US back loans". BBC. 27 March 2014.

- Lukas I. Alpert, Alexander Kolyandr. "Medvedev visits Crimea, vows development aid". Market Watch.

- Sputnik. "Sputnik International - Breaking News & Analysis - Radio, Photos, Videos, Infographics". voiceofrussia.com.

- Sputnik (April 11, 2014). "Crimean Parliament Approves New Constitution". ria.ru.

- Verbyany, Volodymyr (June 1, 2014). "Crimea Adopts Ruble as Ukraine Continues Battling Rebels". Bloomberg.

- Crimea switches to Russian telephone codes, Interfax-Ukraine (7 May 2015)

- Jess McHugh (15 July 2015). "Putin Eliminates Ministry Of Crimea, Region Fully Integrated Into Russia, Russian Leaders Say". International Business Times. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

Further reading

- Allworth, Edward, ed. Tatars of the Crimea. Return to the Homeland (Duke University Press. 1998), articles by scholars

- Barker, W. Burckhardt (1855). A short historical Account of the Crimea, from the earliest ages and during the Russian occupation. old fashioned and anti-Russian.

- Cordova, Carlos. Crimea and the Black Sea: An environmental history. (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015.)

- Dickinson, Sara. "Russia's First 'Orient': Characterizing the Crimea in 1787." Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 3.1 (2002): 3-25. online

- Fisher, Alan (1981). "The Ottoman Crimea in the Sixteenth Century". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 5 (2): 135–143.

- Kizilov, Mikhail B. (2005). "The Black Sea and the Slave Trade: The Role of Crimean Maritime Towns in the Trade in Slaves and Captives in the Fifteenth to Eighteenth Centuries". International Journal of Maritime History. 17 (1): 211–235. doi:10.1177/084387140501700110.

- Kirimli, Hakan. National Movements and National Identity Among the Crimean Tatars (1905 - 1916) (E.J. Brill. 1996)

- Milner, Thomas. The Crimea: Its Ancient and Modern History: the Khans, the Sultans, and the Czars. Longman, 1855. online

- O'Neill, Kelly. Claiming Crimea: A History of Catherine the Great's Southern Empire (Yale University Press, 2017).

- Ozhiganov, Edward. "The Crimean Republic: Rivalries for Control." in Managing Conflict in the Former Soviet Union: Russian and American Perspectives (MIT Press. 1997). pp. 83–137.

- Pleshakov, Constantine. The Crimean Nexus: Putin's War and the Clash of Civilizations (Yale University Press, 2017).

- Sasse, Gwendolyn. The Crimea Question: Identity, Transition, and Conflict (2007)

- Schonle, Andreas (2001). "Garden of the Empire: Catherine's Appropriation of the Crimea". Slavic Review. 60 (1): 1–22. doi:10.2307/2697641. JSTOR 2697641.

- UN-HABITAT (2007). Housing, Land, and Property in Crimea. UN-HABITAT. ISBN 9789211319200., recent developments

- Williams, Brian Glyn. The Crimean Tatars: The Diaspora Experience and the Forging of a Nation (Brill 2001) online

Historiography

- Kizilov, Mikhail; Prokhorov, Dmitry. "The Development of Crimean Studies in the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, and Ukraine," Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae (Dec 2011), Vol. 64 Issue 4, pp437–452.

Primary sources

- Neilson, Mrs. Andrew (1855). The Crimea, its towns, inhabitants and social customs, by a lady resident near the Alma.; complete text online

- Wood, Evelyn. The Crimea in 1854, and 1894: With Plans, and Illustrations from Sketches Taken on the Spot by Colonel W. J. Colville (2005) excerpt and text search