Kropyvnytskyi

Kropyvnytskyi (Ukrainian: Кропивни́цький, romanized: Kropyvnyc'kyj [kropɪu̯ˈnɪtsʲkɪj] (![]()

Kropyvnyćkyj Кропивни́цький Kirovohrad | |

|---|---|

%2C_33.jpg)  .jpg)   | |

| Nickname(s): Little Paris (used in historical context) | |

| Motto(s): With peace and goodness | |

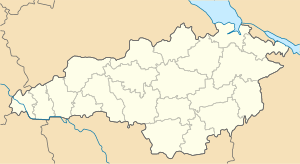

Kropyvnytskyi Location of Kropyvnytskyi  Kropyvnytskyi Kropyvnytskyi (Ukraine) | |

| Coordinates: 48°30′0″N 32°16′0″E | |

| Country | |

| Oblast | |

| Raion | City municipality of Kropyvnytskyi |

| Founded | 1754 |

| City rights | 1765, 1782 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Andriy Raykovych |

| Area | |

| • City of regional significance | 103 km2 (40 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 124 m (407 ft) |

| Population (2013) | |

| • City of regional significance | 234,322 |

| • Density | 2,300/km2 (5,900/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 242,919 |

| Postal code | 25000-490 |

| Area code(s) | +380 522 |

| Sister cities (Bulgaria) | Dobrich |

| Website | kr-rada |

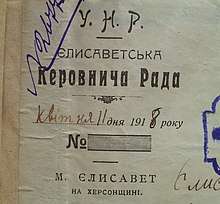

Over its history, Kropyvnytskyi has changed its name several times. The settlement was known as Yelisavetgrad (Ukrainian: Єлисаветгра́д [jɛlʲisavʲɛtɣrad]) after Empress Elizabeth of Russia (r. 1741–1761) from 1752 to 1924 as well as simply Elysavet.[2] In 1924 it became Zinovyevsk (Ukrainian: Зінов'э́вськ, [zʲinɔvɛ́vsʲk]) in honour of the Bolshevik revolutionary and Politburo member Grigory Zinoviev (1883-1936), who was born there. Following the assassination of the First Secretary of the Leningrad City Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Sergei Kirov (in office 1926–1934), the town was renamed Kirovo (Ukrainian: КІ́рово [kʲírɔvɔ]) in Kirov's honour on 7 December 1934 - a name-change similar to those of numerous other localities throughout the USSR (including present-day Kirov in Kirov Oblast, Kirovakan, Kirovabad, as well as multiple instances of Kirovsk, Kirovo, Kirovsky and other derivatives). Concurrently with the formation of the Kirovohrad Oblast on 10 January 1939, and to distinguish it from the Kirov Oblast in central Russia, Kirovo was renamed Kirovohrad (Ukrainian: Кіровогра́д [kirowoˈɦrɑd]; Russian: Кировогра́д, romanized: Kirovograd), a name it maintained until 2016.[3] Due to mandated decommunization the name of the city then changed to Kropyvnytskyi, in honour of the writer, actor and playwright Marko Kropyvnytskyi (1840-1910), who was born near the city.[3] However the Kirovohrad Oblast was not renamed because it is mentioned in the Constitution of Ukraine - only a constitutional amendment could change the name of the oblast.[4]

Notable figures born in the city include Grigory Zinoviev, Volodymyr Vynnychenko, Arseny Tarkovsky, African Spir, Marko Kropyvnytskyi, and others.

Name origins

Yelisavetgrad

The name Yelisavetgrad (usually spelled Elisavetgrad or Elizabethgrad in English language publications) is believed to have evolved as the amalgamation of the fortress name and the common Eastern Slavonic element "-grad" (Old/Church Slavonic "градъ", "a settlement encompassed by a wall"). Its first documented usage dates back to 1764, when Yelisavetgrad Province was organized together with the Yelisavetgrad Lancer Regiment.

Presenting a letter of grant on January 11, 1752, to Major-General Jovan Horvat, the organizer of Nova Serbia settlements, the Empress Elizabeth of Russia ordered "to found an earthen fortress and name it Fort St. Elizabeth" (see On the Historical Meaning of the Name Elizabeth for Our City) (in Ukrainian). Thus simultaneously the future city was named in honour of its formal founder, the Russian empress, and also in honor of her heavenly patroness, St. Elizabeth.

Zinovievsk

Following the Russian Revolution and founding of the Soviet Union, in 1924 the city was renamed Zinovievsk, (also spelled Zinovyevsk), after Grigory Zinoviev, a Soviet statesman and one of the leaders of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks).[5] He was born in Yelisavetgrad on September 20 (September 8 O.S.), 1883. At the time he was honored by the name, he was a member of the Politburo and the Chairman of the Comintern's Executive Committee.

Kirovo and Kirovograd

On December 27, 1934, after the assassination of Sergei Kirov, Zinovievsk and other Soviet cities was renamed again - this time as Kirovo, and then as Kirovograd.[5] The latter name appeared simultaneously with the creation of Kirovograd Oblast, on January 10, 1939[5] and was aimed at differentiating the region from Kirov Oblast in present-day Russia.

After Ukraine regained independence, the name of the city started to be spelled according to Ukrainian pronunciation as Kirovohrad. The previous Russified orthography remains widely used on account of the widespread use of the Russian language in the region.

Kropyvnytskyi

Since 1991 numerous discussions had been held on the city's name. A number of activists supported returning the city to its original name, Yelisavetgrad (or now Yelysavethrad in Ukrainian transcription). Other suggestions for contemporary Ukraine included Tobilevychi (in honour of the Tobilevych family, the Coryphaei of the classic Ukrainian drama established in Yelisavetgrad in 1882); Zlatopil, from Ukrainian "золоте поле", literally "golden field"; and Stepohrad, Ukrainian for "city of steppes" (in recognition of the agricultural status of the city); Ukrayinsk or Ukrayinoslav, i.e. "the glorifying Ukraine one;" and Novokozachyn (to commemorate the semi-fabulous Cossack regiment which could have been quartered at the present-day city location).

The President of Ukraine, Petro Poroshenko, signed the bill banning Communist symbols on May 15, 2015, which required places associated with communism to be renamed within a six-month period.[6] On 25 October 2015 (during local elections) 76.6% of the Kirovohrad voters voted for renaming the city to Yelisavetgrad.[7] A draft law at the time before the Ukrainian parliament would prohibit any names associated with Russian history since the 14th century, which would make the name Yelisavetgrad inadmissible as well.[8] A committee of the Verkhovna Rada (Ukraine's parliament) chose the name Inhulsk on 23 December 2015. This name is a reference to the nearby Inhul river.[9] On 31 March 2016 the State Construction, Regional Policy and Local Self-Government committee of the Verkhovna Rada recommended to parliament to rename Kirovohrad to Kropyvnytskyi.[10] This name is a reference to writer, actor and playwright Marko Kropyvnytskyi, who was born near the city.[10] On 14 July 2016, the name of the city was finally changed to Kropyvnytskyi.[5][11][12]

History

18th and 19th century: from military settlement to trade centre

The history of the city beginnings dates back to the year 1754 when Fort St. Elizabeth was built on the lands of former Zaporizka Sich in the upper course of the Inhul, Suhokleya and Biyanka Rivers. The fort was built in 1754 by the will of the empress Elizabeth of Russia and it played a pivotal role in the new lands added to Russia by the Belgrad Peace Treaty of 1739. In 1764 the settlement received status of the center of the Elizabeth province, and in 1784 the status of chief town of a district, when it was renamed after the fort as Yelizavetgrad.

The Fort of St. Elizabeth was on a crossroads of trade routes, and it eventually became a major trade center. The city has held regular fairs four times a year. Merchants from all over the Russian Empire have visited these fairs. Also, there were numerous foreign merchants, especially from Greece. Developed around the military settlement, the city rose to prominence in the 19th century when it became an important trade centre, as well as a Ukrainian cultural leader with the first professional theatrical company in either Central or Eastern Ukraine being established here in 1882,[5] founded by Mark Kropyvnytsky,[5] Tobilevych brothers and Maria Zankovetska.[5]

Early 20th century: famine and pogroms

Elizabethgrad was ravaged by famine in 1901 and its residents suffered more due to poor government response. The region is extremely fertile. However, a drought in 1892 and poor farming methods which never allowed the soil to recover, prompted a large famine that plagued the region. According to a 1901 New York Times article, the Ministry of the Interior denied that the persistence of famine in the region and blocked non-State charities from bringing aid to the area. The reporter wrote, "The existence of famine was inconvenient at a time when negotiations were pending for foreign loans." The governor of the Kherson region, Prince Oblonsky, refused to acknowledge this famine. One non-resident and non-State worker entered Elizabethgrad and provided the New York Times with an eyewitness account.[13] He observed: general and acute destitution; deaths from starvation; widespread typhus (shows poverty), and little to no work to be found in the region.

Elizabethgrad was located in the Pale of Settlement and, during the 19th century, had a substantial Jewish population.

Elizabethgrad was subjected to several violent pogroms in the late 19th and early 20th century. In 1905 another riot flared, with Christians killing Jews and plundering the Jewish quarter.[14] A contemporary account was reported in the New York Times on December 13, 1905.[15]

Russian revolution and civil war

During the Russian Civil War, the city witnessed intense fighting.

On 7 May 1919, paramilitary leader, and former divisional general in the Red Army, Nikifor Grigoriev, launched an anti-Bolshevik uprising. On 8 May 1919, he issued a proclamation "To the Ukrainian People" (До Українського народу), in which he called upon the Ukrainian people to rise against the "Communist imposters", singling out the "Jewish commissars"[16] and the Cheka. In only a few weeks, Grigoriev's troops perpetrated 148 pogroms, the deadliest of which resulted in the massacre of upwards of 1,000 Jewish people in Yelisavetgrad, from 15 to 17 May 1919.[16] In total, about 3,000 Jews died in the city.[17]

The Soviet Red Army eventually reconquered the city in 1920.

Soviet rule

During Soviet rule, the city economy was dominated by such enterprises as Chervona Zirka Agricultural Machinery Plant (current name Elvorti; which once provided more than 50% of the USSR need in tractor seeders), Hydrosila Hydraulic Units Plant, Radiy Radio Component Plant, Pishmash Typewriter Plant (de facto defunct nowadays) and others.

In World War II Kropyvnytskyi was occupied by Nazi Germany from 5 August 1941. It was subsequently recaptured by Soviet forces on 8 January 1944.

Ukrainian independence

During the Ukrainian presidential election of 2004, the city got country-wide notoriety because of mass election fraud committed by local authorities. It became known as District 100 (the community number according to Central Elections Committee).

Historical heritage

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

From 1878 to 1905 Oleksandr Pashutin was mayor of the city. Under his administration, the city made advances in education and medicine, construction of the water-supply system and several public buildings, introduction of the first tram, and establishing some market places. Yelizavethrad is noted for its architectural quality, with European-type sculpture and old windows. Surviving are a range of classical and modern monuments, Mooresque and Baroque palaces, and buildings that combine Gothic, Rococo and Renaissance motives. A high level of building technology of Yelizavethrad's masters encourages construction and restoration these days.

The history of Kropyvnytskyi consists of memorable events and biographies of famous people. One of the creators of the unsurpassed modern architectural ensemble of the historical centre of the city of Yelisavethrad, Y. Pauchenko was born and lived here. Such noted architects as A. Dostoyevskyi and O. Lishnevskyi worked here, too. P. Kalnyshevsky fought for the Cossacks' freedom on these lands, M. Pirohov laid the foundation of field surgery, M. Kutuzov planned his military operations. Kirovohraders listened to the lectures of the outstanding slavist V. Hryhorovych, and inherited the fundamental investigations of the native land carried out by the ethnographer, historian, archeologist V. Yastrebov.

In different periods of time the history of our region was connected with the names of the famous Ukrainian writer, playwright, publicist and statesman V. Vynnychenko, the poet, literary and cultural critic Y. Malanyuk, the physicist-theoretician, the Nobel Prize laureate I. Tamm, the scientist and inventor, one of the creators of the legendary "Katyusha" G. Langeman, the composer Y. Meytus, the pianist and pedagogue G. Neigauz, the artist and painter O. Osmiorkin, the poet and translator A. Tarkovskyi, the public and cultural figure, memoirist, patron of the arts Y. Chykalenko, the composer, pianist, pedagogue, musician and publicist K. Shymanovskyi, Ukrainian writer, dramatist and script-writer Y. Yanovskyi.

Geography

The city is in the center of Ukraine and within the Dnieper Upland. The Inhul river flows through Kropyvnytskyi. Within the city, several other smaller rivers and brooks runs in the Inhul; they include the Suhoklia and the Biyanka.

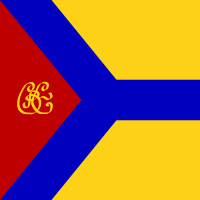

Symbols

Three blue stripes crossed in the middle of the fortress plan symbolize the fortification location at the confluence of the Inhul, Suhukleya and Biyanka rivers. The crimson colour favoured by Cossacks refers to the fortress being situated on the lands of Zaporozky Cossacks. Golden ears together with a golden field on the shield are symbols of the fertile lands and agricultural wealth of the region.

The shield is held by storks, which symbolize happiness, fertility, and love for the native land. The golden tower in the form of a crown expresses that this coat of arms belongs to the regional centre. The motto "With peace and good" placed on the azure stripe emphasizes the same idea. All the details of the flag correlate with the main elements of the shield on the coat of arms of the city.

Administrative status

Today Kropyvnytskyi is a city of oblast significance with 244,000 inhabitants. It is divided into two districts — Fortechnyi and Podilskyi. The urban-type settlement of Nove is part of the Fortechnyi district. Kropyvnytskyi serves as the administrative center of Kirovohrad Raion, though administratively it does not belong to the raion.

Demography

2001 Ukrainian census[18]

- 85.8% - Ukrainians

- 12.0% - Russians

- 0.5% - Belarusians

- 1.7% - others

Historical dynamic

| 1897[19] | 1926[20] | 1939[21] | 1959[22] | 1989[23] | 2001[23] | |

| Ukrainians | 23,6% | 44,6% | 72,0% | 75,0% | 76,9% | 85,8% |

| Russians | 34,6% | 25,0% | 10,9% | 18,6% | 19,5% | 12,0% |

| Belarusians | 0,1% | 0,2% | 0,4% | 0,8% | 0,8% | 0,5% |

| Moldavians | 0,03% | 0,2% | 0,7% | 0,4% | 0,5% | 0,3% |

| Jews | 37,8% | 27,7% | 14,6% | 4,4% | 1,9% | 0,1% |

Notable people

- Irina Belotelkin, artist and fashion designer

- Felix Blumenfeld, composer and pianist born there

- Aaron Bodansky, biochemist

- Olesya Dudnik, Soviet gymnast

- Israel Fisanovich, Soviet Navy submarine commander, hero of the Soviet Union

- Grigory Gamarnik, USSR, world champion (Greco-Roman lightweight), world championship silver[24]

- Moses Gomberg, chemist

- Boris Hessen, historian of science

- Andrei Kanchelskis, Russian-Ukrainian footballer

- Yevhen Konoplyanka, footballer

- Zevulun "Zavel" Kwartin, Jewish cantor

- Dmytro Mykhaylenko, footballer

- Heinrich Neuhaus, Russian pianist and pedagogue of German and Polish descent

- Yury Olesha, writer

- Victor Orly, French painter, born in Kirovohrad.

- Maurice Podoloff, American Hockey League and National Basketball Association pioneer/executive

- Platon Poretsky (1846-1907), mathematician

- Valeriy Porkujan, Soviet footballer

- Andriy Rusol, football player

- African Spir (or Afrikan Spir), philosopher

- Alexei Suetin, Soviet-Russian International Grandmaster of chess and author

- Arseny Tarkovsky, Russian poet

- Alexander Zaldostanov, leader of the Night Wolves; Russia's largest motorcycle club

- Grigory Zinoviev, Bolshevik revolutionary and a Soviet Communist politician

Climate

Kropyvnytskyi is in the central region of Ukraine. Kropyvnytskyi's climate is moderate continental: cold and snowy winters, and hot summers. The seasonal average temperatures are not too cold in winter, not too hot in summer: −4.8 °C (23.4 °F) in January, and 20.7 °C (69.3 °F) in July. The average precipitation is 534 mm (21 in) per year, with the most in June and July.

| Climate data for Kropyvnytskyi, Ukraine (1949-2011) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 11.1 (52.0) |

18.7 (65.7) |

22.8 (73.0) |

28.9 (84.0) |

36.0 (96.8) |

35.5 (95.9) |

38.1 (100.6) |

39.4 (102.9) |

35.0 (95.0) |

28.9 (84.0) |

22.0 (71.6) |

15.7 (60.3) |

39.4 (102.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −2.2 (28.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

4.8 (40.6) |

14.4 (57.9) |

21.0 (69.8) |

24.6 (76.3) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.1 (79.0) |

20.5 (68.9) |

13.2 (55.8) |

5.3 (41.5) |

0.1 (32.2) |

12.7 (54.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −4.8 (23.4) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

0.8 (33.4) |

9.0 (48.2) |

15.3 (59.5) |

18.8 (65.8) |

20.7 (69.3) |

19.9 (67.8) |

14.6 (58.3) |

8.3 (46.9) |

2.1 (35.8) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

8.2 (46.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −7.8 (18.0) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

3.8 (38.8) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.9 (55.2) |

14.7 (58.5) |

13.8 (56.8) |

8.9 (48.0) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

3.6 (38.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −30.0 (−22.0) |

−31.1 (−24.0) |

−25.0 (−13.0) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

0.8 (33.4) |

1.2 (34.2) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

−21.2 (−6.2) |

−26.1 (−15.0) |

−31.1 (−24.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 33.1 (1.30) |

30.7 (1.21) |

33.8 (1.33) |

46.1 (1.81) |

44.0 (1.73) |

70.7 (2.78) |

76.2 (3.00) |

53.3 (2.10) |

36.4 (1.43) |

28.1 (1.11) |

35.0 (1.38) |

46.7 (1.84) |

534.1 (21.03) |

| Average precipitation days | 20.0 | 17.3 | 15.3 | 7.9 | 9.6 | 8.6 | 5.6 | 4.0 | 7.9 | 10.5 | 15.2 | 18.4 | 140.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 86.3 | 83.8 | 77.1 | 62.2 | 61.6 | 65.9 | 66.8 | 62.4 | 70.5 | 78.2 | 86.8 | 88.5 | 74.2 |

| Source: Climatebase.ru[25] | |||||||||||||

See also

- Kropyvnytskyi Region Universal Research Library

- Remember about the Gas — Do not buy Russian goods!

References

- "Чисельність наявного населення України (Actual population of Ukraine)" (PDF) (in Ukrainian). State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- Mikhail Levchenko. Hanshchyna (Ганьщина Україна). Opyt russko-ukrainskago slovari︠a︡. Tip. Gubernskago upravlenii︠a︡, 1874.

- Goodbye, Lenin: Ukraine moves to ban communist symbols, BBC News (14 April 2015)

(in Ukrainian) Verkhovna Rada renamed Kirovograd, Ukrayinska Pravda (14 July 2016) - Ukraine, The World Factbook.

- Sweeping out Soviet past: Kirovohrad renamed Kropyvnytsky, UNIAN (14 July 2016)

- "Poroshenko signs laws on denouncing Communist, Nazi regimes". Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- "77% of Kirovograd residents favor return of city's name of Yelisavetgrad - media". Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- "Ukrainian Parliament introduced a bill to ban all Russian geographic names starting from the XIV century". Archived from the original on 24 December 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- "Комитет Рады предлагает переименовать Кировоград в Ингульск, - Вятрович". Censor.

- (in Ukrainian) Profile Committee of the Council decided on a new name for Kirovohrad, Ukrayinska Pravda (31 March 2016)

- (in Ukrainian) Verkhovna Rada renamed Kirovograd, Ukrayinska Pravda (14 July 2016)

- "Офіційний портал Верховної Ради України". Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- "Famine and Disease in South Russia Province" New York Times, 5 Aug. 1901. New York Times. 26 June 2009 .

- Rosenthal, Herman. Broyde, Isaac. Janovsy, S. Jewish Encyclopedia.com "Yelisavetgrad:Elisavetgrad", accessed June 20, 2009

- "Russian City Burning; Jews Are Massacred," NY Times, 12 Dec. 1905, accessed 25 June 2009 .

- Werth, Nicolas (2019). "Chap. 5: 1918-1921. Les pogroms des guerres civiles russes". Le cimetière de l’espérance. Essais sur l’histoire de l’Union soviétique (1914-1991) [Cemetery of Hope. Essays on the History of the Soviet Union (1914–1991)]. Collection Tempus (in French). Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-07879-9.

- "Микола Правда — Отаман Григор'єв, яким він був насправді — «Молодіжне перехрестя», 23.10.2008". Archived from the original on 2015-11-20. Retrieved 2015-11-20.

- "Всеукраїнський перепис населення 2001 - Результати - Основні підсумки - Національний склад населення - Кіровоградська область:". Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- "Демоскоп Weekly - Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей". Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- Population census, 1926 year

- "Демоскоп Weekly - Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей". Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- Кабузан В. М. — Archived 2014-12-31 at the Wayback Machine

- "Всеукраїнський перепис населення 2001 - Результати - Основні підсумки - Національний склад населення:". Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- "YIVO - Sport: Jews in Sport in the USSR". Archived from the original on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- "Climatological Normals for Kropyvnytskyi, Ukraine (1949-2011)". Climatebase. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kropyvnytskyi. |

| Look up kropyvnytskyi in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Kropyvnytskyi Daily News (in Ukrainian and Russian)

- Bez Kupur - News of Kropyvnytskyi and Kirovohrad region without limits on the truth (in Ukrainian)

- Online magazine for young people - "Grechka". News about the cultural life of Kropyvnytskyi young people and Kropyvnytskyi region young people.

- Kropyvnytskyi's portal: photos, news, information, etc. (in Russian)

- Kropyvnytskyi news, history of the city, photos, science. (in Ukrainian)

- Kropyvnytskyi events, history of the city, photos, news and chats with citizen (in Ukrainian)