Deportation of the Crimean Tatars

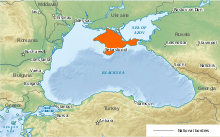

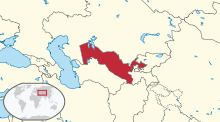

The deportation of the Crimean Tatars (Crimean Tatar: Qırımtatar halqınıñ sürgünligi; Ukrainian: Депортація кримських татар; Russian: Депортация крымских татар) or the Sürgünlik ("exile") was the ethnic cleansing of at least 191,044[c 1] Crimean Tatars in 18–20 May 1944 carried out by the Stalinist regime, specifically by Lavrentiy Beria, head of the Soviet state security and secret police, acting on behalf of Joseph Stalin. Within three days, Beria's NKVD used cattle trains to deport mostly women, children, the elderly, even Communists and members of the Red Army, to the Soviet Republic of Uzbekistan, several thousand kilometres away. They were one of the ten ethnicities who were encompassed by Stalin's policy of population transfer in the Soviet Union.

| Deportation of the Crimean Tatars | |

|---|---|

| Part of Forced population transfer in the Soviet Union and World War II | |

Left to right, top to bottom: Memorial to the deportation in Eupatoria; candle-lighting ceremony in Kiev; memorial rally in Taras Shevchenko park; cattlecar similar to the type used in the deportation; maps comparing the demographics of Crimea in 1939 and 2001. | |

| Location | Crimean Peninsula |

| Date | 18–20 May 1944 |

| Target | Crimean Tatars |

Attack type | forced population transfer, ethnic cleansing |

| Deaths | Several estimates a) 34,000[1] b) 40,000–44,000[2] c) 42,000[3] d) 45,000[4] e) 109,956[5] (between 18 and 46 percent of their total population[6]) |

| Perpetrators | NKVD, the Soviet secret police |

| Part of a series on |

| Population transfer in the Soviet Union |

|---|

| Policies |

| Peoples |

|

| Operations |

| WWII POW labor |

| Massive labor force transfers |

|

The deportation officially was intended as collective punishment for the perceived collaboration of some Crimean Tatars with Nazi Germany, in spite of hostile attitudes to Crimean Tatars from the Nazis, who considered Crimean Tatars to be "racially inferior" and "Mongol sub-humanity"; modern sources theorize that the deportation was part of the Soviet plan to gain access to the Dardanelles and acquire territory in Turkey where the Tatars had ethnic kinsmen.

Nearly 8,000 Crimean Tatars died during the deportation, while tens of thousands perished subsequently due to the harsh exile conditions. The Crimean Tatar exile resulted in the abandonment of 80,000 households and 360,000 acres of land. An intense campaign of detatarization to erase remaining traces of Crimean Tatar existence followed. In 1956, the new Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, condemned Stalin's policies, including the deportation of various ethnic groups, but did not lift the directive forbidding the return of the Crimean Tatars, despite allowing the right of return for most other deported peoples. They remained in Central Asia for several more decades until the Perestroika era in the late 1980s when 260,000 Crimean Tatars returned to Crimea. Their exile lasted 45 years. The ban on their return was officially declared null and void, and the Supreme Council of Crimea declared on 14 November 1989 that the deportations had been a crime.

By 2004, sufficient numbers of Crimean Tatars had returned to Crimea that they comprised 12 percent of the peninsula's population. Soviet authorities neither assisted their return nor compensated them for the land they lost. The Russian Federation, the successor state of the USSR, did not provide reparations, compensate those deported for lost property, or file legal proceedings against the perpetrators of the forced resettlement. The deportation was a crucial event in the history of the Crimean Tatars and has come to be seen as a symbol of the plight and oppression of smaller ethnic groups by the Soviet Union. On 12 December 2015, the Ukrainian Parliament issued a resolution recognizing this event as genocide and established 18 May as the "Day of Remembrance for the victims of the Crimean Tatar genocide".

Background

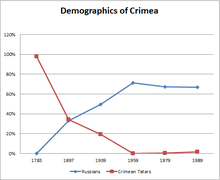

The Crimean Tatars controlled the Crimean Khanate from 1441 to 1783, when Crimea was annexed by the Russian Empire as a target of Russian expansion. By the 14th century, most of the Turkic-speaking population of Crimea had adopted Islam, following the conversion of Ozbeg Khan of the Golden Horde. It was the longest surviving state of the Golden Horde.[8] They often engaged in conflicts with Moscow—from 1468 until the 17th century, Crimean Tatars were averse to the newly-established Russian rule. Thus, Crimean Tatars began leaving Crimea in several waves of emigration. Between 1784 and 1790, out of a total population of about a million, around 300,000 Crimean Tatars left for the Ottoman Empire.[9]

The Crimean War triggered another mass exodus of Crimean Tatars. Between 1855 and 1866 at least 500,000 Muslims, and possibly up to 900,000, left the Russian Empire and emigrated to the Ottoman Empire. Out of that number, at least one third were from Crimea, while the rest were from the Caucasus. These emigrants comprised 15–23 per cent of the total population of Crimea. The Russian Empire used that fact as the ideological foundation to further Russify "New Russia".[10] Eventually, the Crimean Tatars became a minority in Crimea; in 1783, they comprised 98 per cent of the population,[11] but by 1897, this was down to 34.1 per cent.[12] While Crimean Tatars were emigrating, the Russian government encouraged Russification of the peninsula, populating it with Russians, Ukrainians, and other Slavic ethnic groups; this Russification continued during the Soviet era.[12]

After the 1917 October Revolution, Crimea received autonomous status inside the USSR on 18 October 1921,[13] but collectivization in the 1920s led to severe famine from which up to 100,000 Crimeans perished when their crops were transported to "more important" regions of the Soviet Union.[14] By one estimate, three-quarters of the famine victims were Crimean Tatars.[13] Their status deteriorated further after Joseph Stalin became the Soviet leader and implemented repressions that led to the deaths of at least 5.2 million Soviet citizens between 1927 and 1938.[15]

World War II

In 1940, the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic had approximately 1,126,800 inhabitants, of which 218,000 people, or 19.4 percent of the population, were Crimean Tatars.[16] In 1941, Nazi Germany invaded Eastern Europe, annexing much of the western USSR. Crimean Tatars initially viewed the Germans as liberators from Stalinism, and they had also been positively treated by the Germans in World War I.[17]

Many of the captured Crimean Tatars serving in the Red Army were sent to POW camps after Romanians and Nazis came to occupy the bulk of Crimea. Though Nazis initially called for murder of all "Asiatic inferiors" and paraded around Crimean Tatar POW's labeled as "Mongol sub-humanity",[18][19] they revised this policy in the face of determined resistance from the Red Army. Beginning in 1942, Germans recruited Soviet prisoners of war to form support armies.[20] The Dobrucan Tatar nationalist Fazil Ulkusal and Lipka Tatar Edige Kirimal helped in freeing Crimean Tatars from German prisoner-of-war camps and enlisting them in the independent Crimean support legion for the Wehrmacht. This legion eventually included eight battalions.[17] From November 1941, German authorities allowed Crimean Tatars to establish Muslim Committees in various towns as a symbolic recognition of some local government authority, though they were not given any political power.[21]

| Year | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 1783 | 500,000 | 98% |

| 1897 | 186,212 | 34.1% |

| 1939 | 218,879 | 19.4% |

| 1959 | — | — |

| 1979 | 5,422 | 0.3% |

| 1989 | 38,365 | 1.6% |

Many Crimean Tatar communists strongly opposed the occupation and assisted the resistance movement to provide valuable strategic and political information.[21] Other Crimean Tatars also fought on the side of the Soviet partisans, like the Tarhanov movement of 250 Crimean Tatars which fought throughout 1942 until its destruction.[23] Six Crimean Tatars were even named the Heroes of the Soviet Union, and thousands more were awarded high honors in the Red Army.

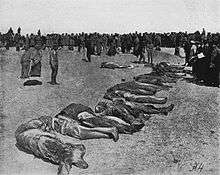

Up to 130,000 people died during the Axis occupation of Crimea.[24] The Nazis implemented a brutal repression, destroying more than 70 villages that were together home to about 25 per cent of the Crimean Tatar population. Thousands of Crimean Tatars were forcibly transferred to work as Ostarbeiter in German factories under the supervision of the Gestapo in what were described as "vast slave workshops", resulting in loss of all Crimean Tatar support.[25] In April 1944 the Red Army managed to repel the Axis forces from the peninsula in the Crimean Offensive.[26]

A majority of the hiwis (helpers), their families and all those associated with the Muslim Committees were evacuated to Germany and Hungary or Dobruca by the Wehrmacht and Romanian army where they joined the Eastern Turkic division. Thus, the majority of the collaborators had been evacuated from Crimea by the retreating Wehrmacht.[27] Many Soviet officials had also recognized this and rejected claims that the Crimean Tatars had betrayed the Soviet Union en masse. The presence of Muslim Committees organized from Berlin by various Turkic foreigners appeared a cause for concern in the eyes of the Soviet government, already weary of Turkey at the time.[28]

- Falsification of information in propaganda

Soviet publications blatantly falsified information about Crimean Tatars in the Red Army, going so far as to describe Crimean Tatar Hero of the Soviet Union Uzeir Abduramanov as Azeri, not Crimean Tatar, on the cover of a 1944 issue of Ogonyok magazine - even though his family had been deported for being Crimean Tatar just a few months earlier.[29][30] The book "In the Mountains of Tavria" falsely claimed volunteer partisan scout Bekir Osmanov was a German spy and shot, although the central committee later acknowledged that he never served the Germans and survived the war, ordering later editions to have corrections after still-living Osmanov and his family noticed the obvious falsehood.[31]

Deportation

| We were told that we were being evicted and we had 15 minutes to get ready to leave. We boarded boxcars – there were 60 people in each, but no one knew where we were being taken to. To be shot? Hanged? Tears and panic were taking over.[32] |

| — Saiid, who was deported with his family from Yevpatoria when he was 10 |

Officially due to the collaboration with the Axis Powers during World War II, the Soviet government inflicted a collective guilt and punishment on ten ethnic minorities,[33] among them the Crimean Tatars.[34] Punishment included deportation to distant regions of Central Asia and Siberia.[33] Soviet accounts of the late 1940s indict the Crimean Tatars as an ethnicity of traitors. Although refused by Crimean Tatars, this opinion was widely accepted in the Soviet period and persists in the Russian scholarly and popular literature.[35]

On 10 May 1944, Lavrentiy Beria recommended to Stalin that the Crimean Tatars should be deported away from the border regions due to their "traitorous actions".[36] Stalin subsequently issued GKO Order No. 5859ss, which envisaged the resettlement of the Crimean Tatars.[37] The deportation lasted only three days,[38] 18–20 May 1944, during which NKVD agents went house to house collecting Crimean Tatars at gunpoint and forcing them to enter sealed-off[39] cattle trains that would transfer them almost 3,200 kilometres (2,000 mi)[40] to remote locations in the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic. The Crimean Tatars were allowed to carry up to 500 kg of their property per family.[41] By 8:00 on the first day, the NKVD had already loaded 90,000 Crimean Tatars distributed in 25 trains.[42] The next day, a further 136,412 persons were boarded onto railroad cars.[42] The only ones who could avoid this fate were Crimean Tatar women who were married to men of other non-punished ethnic groups.[43] They travelled in overcrowded wagons for several weeks and were plagued by a lack of food and water.[44] It is estimated that at least 228,392 people were deported from Crimea, of which at least 191,044 were Crimean Tatars[45] in 47,000 families.[46] Since 7,889 people perished in the long transit in sealed-off railcars, the NKVD registered 183,155 Crimean Tatars who arrived at their destinations in Central Asia.[47] The majority of the deportees were rounded up from the Crimean countryside. Only 18,983 of the exiles were from Crimean cities.[48]

On 4 July 1944, the NKVD officially informed Stalin that the resettlement was complete.[49] However, not long after that report, the NKVD found out that one of its units forgot to deport people from the Arabat Spit. Instead of preparing an additional transfer in trains, the NKVD boarded hundreds of Crimean Tatars onto an old boat, took it to the middle of the Azov Sea, and sank the ship, on 20 July. Those who did not drown were finished off by machine-guns.[43]

Officially, Crimean Tatars were eliminated from Crimea. The deportation encompassed every person considered by the government to be Crimean Tatar, including children, women, and the elderly, and even those who had been members of the Communist Party or the Red Army. As such, they were legally designated as special settlers, which meant that they were officially second-class citizens, prohibited from leaving the perimeter of their assigned area, attending prestigious universities, and had to regularly appear before the commandant's office.[50]

During this mass eviction, the Soviet authorities confiscated around 80,000 houses, 500,000 cattle, 360,000 acres of land, and 40,000 tons of agricultural provisions.[51] Besides 191,000 deported Crimean Tatars, the Soviet authorities also evicted 9,620 Armenians, 12,420 Bulgarians, and 15,040 Greeks from the peninsula. All were collectively branded as traitors and became second class citizens for decades in the USSR.[51] Among the deported, there were also 283 persons of other ethnicities: Italians, Romanians, Karaims, Kurds, Czechs, Hungarians, and Croats.[52] During 1947 and 1948, a further 2,012 veteran returnees were deported from Crimea by the local MVD.[16]

In total, 151,136 Crimean Tatars were deported to the Uzbek SSR; 8,597 to the Mari Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic; and 4,286 to the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic; and the remaining 29,846 were sent to various remote regions of the Russian SFSR.[53] When the Crimean Tatars arrived at their destination in the Uzbek SSR, they were met with hostility by Uzbek locals who threw stones at them, even their children, because they heard that the Crimean Tatars were "traitors" and "fascist collaborators."[54] The Uzbeks objected to becoming the "dumping ground for treasonous nations." In the coming years, several assaults against the Crimean Tatars population were registered, some of which were fatal.[54]

The mass Crimean deportations were organized by Lavrentiy Beria, the chief of the Soviet secret police, the NKVD, and his subordinates Bogdan Kobulov, Ivan Serov, B. P. Obruchnikov, M.G. Svinelupov, and A. N. Apolonov. The field operations were conducted by G. P. Dobrynin, the Deputy Head of the Gulag system; G. A. Bezhanov, the Colonel of State Security; I. I. Piiashev, Major General; S. A. Klepov, Commissar of State Security; I. S. Sheredega, Lt. General; B. I. Tekayev, Lt. Colonel of State Security; and two local leaders, P. M. Fokin, head of the Crimea NKGB, and V. T. Sergjenko, Lt. General.[16] In order to execute this deportation, the NKVD secured 5,000 armed agents and the NKGB allocated a further 20,000 armed men, together with a few thousand regular soldiers.[37] Two of Stalin's directives from May 1944 reveal that every aspect of the Soviet government, from financing to transit, was involved in executing the operation.[16]

On 14 July 1944 the GKO authorized the immigration of 51,000 people, mostly Russians, to 17,000 empty collective farms on Crimea. On 30 June 1945, the Crimean ASSR was abolished.[37]

Soviet propaganda sought to hide the population transfer by claiming that the Crimean Tatars had "voluntarily resettle[d] to Central Asia".[55] In essence, though, according to historian Paul Robert Magocsi, Crimea was "ethnically cleansed."[44] After this act, the term Crimean Tatar was banished from the Russian-Soviet lexicon, and all Crimean Tatar toponyms (names of towns, villages, and mountains) in Crimea were changed to Russian names on all maps as part of a wide detatarization campaign. Muslim graveyards and religious objects in Crimea were demolished or converted into secular places.[44] During Stalin's rule, nobody was allowed to mention that this ethnicity even existed in the USSR. This went so far that many individuals were even forbidden to declare themselves as Crimean Tatars during the Soviet censuses of 1959, 1970, and 1979. They could only declare themselves as Tatars. This ban was lifted during the Soviet census of 1989.[56]

Aftermath

Mortality and death toll

| Year | Number of deceased |

|---|---|

| May 1944 – 1 January 1945 | 13,592 |

| 1 January 1945 – 1 January 1946 | 13,183 |

The first deportees started arriving in the Uzbek SSR on 29 May 1944 and most had arrived by 8 June 1944.[58] The consequent mortality rate remains disputed; the NKVD kept incomplete records of the death rate among the resettled ethnicities living in exile. Like the other deported peoples, the Crimean Tatars were placed under the regime of special settlements. Many of those deported performed forced labor:[27] their tasks included working in coal mines and construction battalions, under the supervision of the NKVD. Deserters were executed.[59] Special settlers routinely worked eleven to twelve hours a day, seven days a week.[60] Despite this difficult physical labor, the Crimean Tatars were given only around 200 grams (7.1 oz)[61] to 400 grams (14 oz) of bread per day.[62] Accommodations were insufficient; some were forced to live in mud huts where "there were no doors or windows, nothing, just reeds" on the floor to sleep on.[63]

The sole transport to these remote areas and labour colonies was equally as strenuous. Theoretically, the NKVD loaded 50 people into each railroad car, together with their property.[64] One witness claimed that 133 people were in her wagon.[65] They had only one hole in the floor of the wagon which was used as a toilet.[64] Some pregnant women were forced to give birth inside these sealed-off railroad cars.[66] The conditions in the overcrowded train wagons were exacerbated by a lack of hygiene, leading to cases of typhus.[64] Since the trains only stopped to open the doors at rare occasions during the trip, the sick inevitably contaminated others in the wagons.[64] It was only when they arrived at their destination in the Uzbek SSR that the Crimean Tatars were released from the sealed-off railroad cars.[64] Still, some were redirected to other destinations in Central Asia and had to continue their journey. Some witnesses claimed that they travelled for 24 consecutive days.[67] During this whole time, they were given very little food or water while trapped inside.[44] There was no fresh air since the doors and windows were bolted shut. In Kazakh SSR, the transport guards unlocked the door only to toss out the corpses along the railroad. The Crimean Tatars thus called these railcars "crematoria on wheels."[68] The records show that at least 7,889 Crimean Tatars died during this long journey, amounting to about 4 per cent of their entire ethnicity.[69]

| We were forced to repair our own individual tents. We worked and we starved. Many were so weak from hunger that they could not stay on their feet.... Our men were at the front and there was no one who could bury the dead. Sometimes the bodies lay among us for several days.... Some Crimean Tatar children dug little graves and buried the unfortunate little ones.[70] |

| — anonymous Crimean Tatar woman, describing life in exile |

The high mortality rate continued for several years in exile due to malnutrition, labor exploitation, diseases, lack of medical care, and exposure to the harsh desert climate of Uzbekistan.[71] The exiles were frequently assigned to the heaviest construction sites. The Uzbek medical facilities filled with Crimean Tatars who were susceptible to the local Asian diseases not found on the Crimean peninsula where the water was purer, including yellow fever, dystrophy, malaria, and intestinal illness.[48] The death toll was the highest during the first five years. In 1949 the Soviet authorities counted the population of the deported ethnic groups who lived in special settlements. According to their records, there were 44,887 excess deaths in these five years, 19.6 per cent of that total group.[1][27] Other sources give a figure of 44,125 deaths during that time,[72] while a third source, using alternative NKVD archives, gives a figure of 32,107 deaths.[4] These reports included all the people resettled from Crimea (including Armenians, Bulgarians, and Greeks), but the Crimean Tatars formed a majority in this group. It took five years until the number of births among the deported people started to surpass the number of deaths.[71] Soviet archives reveal that between May 1944 and January 1945 a total of 13,592 Crimean Tatars perished in exile, about 7 per cent of their entire population.[57] Almost half of all deaths (6,096) were of children under the age of 16; another 4,525 were adult women and 2,562 were adult men. During 1945, a further 13,183 people died.[57] Thus, by the end of December 1945, at least 27,000 Crimean Tatars had already died in exile.[73] One Crimean Tatar woman living near Tashkent recalled the events from 1944:

My parents were moved from Crimea to Uzbekistan in May 1944. My parents had sisters and brothers, but when they arrived in Uzbekistan, the only survivors were themselves. My parents' sisters and brothers and parents all died in transit because of catching bad colds and other diseases.... My mother was left completely alone and her first work was to cut trees.[74]

Estimates produced by Crimean Tatars indicate mortality figures that were far higher and amounted to 46% of their population living in exile.[6] In 1968, when Leonid Brezhnev presided over the USSR, Crimean Tatar activists were persecuted for using that high mortality figure under the guise that it was a "slander to the USSR." In order to show that Crimean Tatars were exaggerating, the KGB published figures showing that "only" 22 per cent of that ethnic group died.[6] The Karachay demographer Dalchat Ediev estimates that 34,300 Crimean Tatars died due to the deportation, representing an 18 per cent mortality rate.[1] Hannibal Travis estimates that overall 40,000–80,000 Crimean Tatars died in exile.[75] Professor Michael Rywkin gives a figure of at least 42,000 Crimean Tatars who died between 1944 and 1951, including 7,900 who died during the transit[3]—J. Otto Pohl concludes this would mean that at least 20% of their population died as a consequence of this policy. Pohl described it as "one of the worst cases of ethnically motivated mass murder of the 20th century."[76] Professor Brian Glyn Williams gives a figure of between 40,000 and 44,000 deaths as a consequence of this deportation.[2] The Crimean State Committee estimated that 45,000 Crimean Tatars died between 1944 and 1948. The official NKVD report estimated that 27 per cent of that ethnicity died.[4]

Various estimates of the mortality rates of the Crimean Tatars:

Rehabilitation

Stalin's government denied the Crimean Tatars the right to education or publication in their native language. Despite the prohibition, and although they had to study in Russian or Uzbek, they maintained their cultural identity.[77] In 1956 the new Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, held a speech in which he condemned Stalin's policies, including the mass deportations of various ethnicities. Still, even though many peoples were allowed to return to their homes, three groups were forced to stay in exile: the Soviet Germans, the Meskhetian Turks, and the Crimean Tatars.[78] In 1954, Khrushchev allowed Crimea to be included in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic since Crimea is linked by land to Ukraine and not with the Russian SFSR.[79] On 28 April 1956, the directive "On Removing Restrictions on the Special Settlement of the Crimean Tatars... Relocated during the Great Patriotic War" was issued, ordering a de-registration of the deportees and their release from administrative supervision. However, various other restrictions were still kept and the Crimean Tatars were not allowed to return to Crimea. Moreover, that same year the Ukrainian Council of Ministers banned the exiled Crimean Tatars, Greeks, Germans, Armenians and Bulgarians from relocating even to the Kherson, Zaporizhia, Mykolaiv and Odessa Oblasts in the Ukrainian SSR.[80] The Crimean Tatars did not get any compensation for their lost property.[78]

In the 1950s, the Crimean Tatars started actively advocating for the right to return. In 1957, they collected 6,000 signatures in a petition that was sent to the Supreme Soviet that demanded their political rehabilitation and return to Crimea.[70] In 1961 25,000 signatures were collected in a petition that was sent to the Kremlin.[78]

Mustafa Dzhemilev, who was only six months old when his family was deported from Crimea, grew up in Uzbekistan and became an activist advocating for the right of the Crimean Tatars to return. In 1966 he was arrested for the first time and spent a total of 17 years in prison during the Soviet era. This earned him the nicknamed the "Crimean Tatar Mandela."[81] In 1984 he was sentenced for the sixth time for "anti-Soviet activity," but was given moral support by Soviet dissident Andrei Sakharov who had observed Dzhemilev's fourth trial in 1976.[82] When older dissidents were arrested, a new, younger generation would emerge that would replace them.[78]

On 21 July 1967, the representatives of the Crimean Tatars, led by dissident Ayshe Seitmuratova, gained permission to meet with high-ranking Soviet officials in Moscow, including Yuri Andropov. During the meeting, the Crimean Tatars demanded a correction of all the injustices that the USSR did to their people. In September 1967 the Supreme Soviet issued a decree that granted amnesty to Crimean Tatars with regards to the charges of mass treason during World War II and also gave them more rights in the USSR. Still, though, the Crimean Tatars did not get what they wanted the most: the right to return to Crimea. The carefully worded decree stated that "The citizens of Tatars nationality who had formerly been living on Crimea […] have taken root in the Uzbek SSR."[83] Individuals united and formed groups that went back to Crimea in 1968 on their own, without state permission—only for the Soviet authorities to deport 6,000 of them once again.[84] The most notable example of such resistance was a Crimean Tatar activist Musa Mamut, who had been deported when he was 12 and who returned to Crimea because he wanted to see his home again. When the police informed him that he would be evicted, he poured gasoline over his body and set himself on fire.[84] Despite this, 577 families managed to obtain state permission to reside in Crimea.[85]

In 1968 unrest erupted among the Crimean Tatar people in the Uzbek city of Chirchiq.[86] In October 1973 Jewish poet and professor Ilya Gabay committed suicide by jumping off a building in Moscow. He was one of the significant Jewish dissidents in the USSR who fought for the rights of the oppressed peoples, especially Crimean Tatars. Gabay was arrested and sent to a labour camp, but still insisted on his cause because he was convinced that the treatment of Crimean Tatars by the USSR amounted to genocide.[87] That same year, Dzhemilev was also arrested.[88]

Despite the process of de-Stalinization, it was not until Perestroika and the ascent of Mikhail Gorbachev to power in the late 1980s that things started to change. In 1987 Crimean Tatar activists organized a protest in the centre of Moscow near the Kremlin.[70] This compelled Gorbachev to form a commission to look into this matter. The first conclusion of the commission, led by hardliner Andrei Gromyko, was that there was "no basis to renew autonomy and grant Crimean Tatars the right to return," but Gorbachev ordered a second commission that recommended the renewal of autonomy for Crimean Tatars.[89] Finally, in 1989, the ban on the return of the deported ethnicities was officially declared null and void; the Supreme Council of Crimea also issued a declaration on 14 November 1989 that the previous deportations of peoples were a criminal activity.[51] This paved the way for 260,000 Crimean Tatars to return to their homeland. That same year, Dzhemilev returned to Crimea, and by 1 January 1992 at least 166,000 other Crimean Tatars had done the same.[90] The 1991 Russian law On the Rehabilitation of Repressed Peoples addressed the rehabilitation of all ethnicities repressed in the Soviet Union. It adopted measures which involved the "abolition of all previous RSFSR laws relating to illegally forced deportations" and called for the "restoration and return of the cultural and spiritual values and archives which represent the heritage of the repressed people."[91]

By 2004 the Crimean Tatars formed 12 per cent of the population of Crimea.[92] Despite this, the return of Crimean Tatars was not a simple process: in 1989, when they started their mass return, various Russian nationalists staged protests in Crimea under the slogan: «Tatar traitors - Get out of Crimea!» Several clashes between locals and Crimean Tatars were reported in 1990 near Yalta, which compelled the army to intervene to calm the situation. Local Soviet authorities were reluctant to help Crimean Tatar returnees find a job or a residence.[93] The returnees found 517 abandoned Crimean Tatar villages, but bureaucracy constrained their efforts to restore them.[70] During 1991 at least 117 Crimean Tatar families lived in tents in two meadows near Simferopol, waiting for the authorities to grant them a permanent residence.[94] After the dissolution of the USSR, Crimea found itself a part of Ukraine, but Kiev gave only limited support to Crimean Tatar settlers. Some 150,000 of the returnees were granted citizenship automatically under Ukraine's Citizenship Law of 1991, but 100,000 who returned after the country declared independence faced several obstacles, including a costly bureaucratic process.[95] Since the exile lasted for almost 50 years, some Crimean Tatars decided to stay in Uzbekistan, which led to the separation of families who had decided to return to Crimea.[96] By 2000 there were 46,603 recorded appeals of returnees who demanded a piece of land. A majority of these applications were rejected. Around the larger cities, such as Sevastopol, a Crimean Tatar was on average given only 0.04 acres of land, which was of poor quality or unsuitable for farming.[97]

Modern views and legacy

| The KGB collaborators are furious that we are gathering statistical evidence about Crimean Tatars who perished in exile and that we are collecting materials against the sadist commandants who derided the people during the Stalin years and who, according to the precepts of the Nuremberg Tribunal, should be tried for crimes against humanity. As a result of the crime of 1944, I lost thousands upon thousands of my brothers and sisters. And this must be remembered! [98] |

| — Mustafa Dzhemilev, 1966 |

Ukrainian-Canadian historian Peter J. Potichnyj concludes that the dissatisfaction of the Crimean Tatars over their life in exile mirrors a broader picture of non-Russian ethnic groups of the USSR that started to publicly express their anger against injustices perpetrated by the Greater Russian ideologists.[9] In 1985 an essay by Ukrainian journalist Vasil Sokil entitled Forgetting Nothing, Forgetting No One was published in the Russian emigre journal Kontinent. In an often sarcastic manner, it highlighted the selectively forgotten Soviet citizens and ethnicities who suffered during World War II, but whose experiences disrupt the official Soviet narrative of a heroic victory: "Many endured all the tortures of Hitler's concentration camps only to be sent to the Siberian gulag. […] What, in truth, does a human being need? Not much. Simply to be recognized as humans. Not as an animal." Sokil used the experience of the Crimean Tatars as an example of the ethnicities who were denied this recognition.[99]

Between 1989 and 1994, around a quarter of a million Crimean Tatars migrated from Central Asia to Crimea. This was seen as a symbolic victory of their efforts to return to their native land.[100] They returned after 45 years of exile.[101]

Not one of the ten ethnic groups who were deported during Stalin's era received any kind of compensation.[33] Some Crimean Tatar groups and activists have called for the international community to put pressure on the Russian Federation, the successor state of the USSR, to finance rehabilitation of that ethnicity and provide financial compensation for forcible resettlement.[102]

Despite the thousands of Crimean Tatars in the Red Army when it attacked Berlin, Soviet suspicion focused on this particular group.[103] Some historians explain this as part of Stalin's plan to take complete control of Crimea. The Soviet sought access to the Dardanelles and control of territory in Turkey, where the Crimean Tatars had ethnic kinsmen. By painting the Crimean Tatars as traitors, this taint could be extended to their kinsmen.[104] Scholar Walter Kolarz alleges that the deportation and liquidation of Crimean Tatars as an ethnicity in 1944 was just the final act of the centuries-long process of Russian colonization of Crimea that started in 1783.[9] Historian Gregory Dufaud regards the Soviet accusations against Crimean Tatars as a convenient excuse for their forcible transfer through which Moscow secured an unrivalled access to the geostrategic southern Black Sea on one hand and eliminated hypothetical rebellious nations at the same time.[105] Professor of Russian and Soviet history Rebecca Manley similarly concluded that the real aim of the Soviet government was to "cleanse" the border regions of "unreliable elements".[106] Professor Brian Glyn Williams states that the deportations of Meskhetian Turks, despite never being close to the scene of combat and never being charged with any crime, lends the strongest credence to the fact that the deportations of Crimeans and Caucasians was due to Soviet foreign policy rather than any real "universal mass crimes".[107]

In March 2014 the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation unfolded, which was, in turn, declared illegal by the United Nations General Assembly (United Nations General Assembly Resolution 68/262) and which led to further deterioration of the rights of the Crimean Tatars. Even though the Russian Federation issued Decree No. 268 "On the Measures for the Rehabilitation of Armenian, Bulgarian, Greek, Crimean Tatar and German Peoples and the State Support of Their Revival and Development" on 21 April 2014,[108] in practice it has treated Crimean Tatars with far less care. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights issued a warning against the Kremlin in 2016 because it "intimidated, harassed and jailed Crimean Tatar representatives, often on dubious charges",[38] while the Mejlis, their representative body, was banned.[109]

The UN reported that over 10,000 people left Crimea after the annexation in 2014, mostly Crimean Tatars,[110] which caused a further decline of their fragile community. Crimean Tatars stated several reasons for their departure, among them insecurity, fear, and intimidation from the new Russian authorities.[111] In its 2015 report, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights warned that various human rights violations were recorded in Crimea, including the prevention of Crimean Tatars from marking the 71st anniversary of their deportation.[112] Dzhemilev, who was in Turkey during the annexation, was banned from entering Crimea for five years by the Russian authorities, thus marking the second time that he was evicted from his native land.[113]

Modern interpretations by scholars and historians sometimes classify this mass deportation of civilians as a crime against humanity,[114] ethnic cleansing,[115][100][44] depopulation,[116] an act of Stalinist repression[117] or an "ethnocide", meaning a deliberate wiping out of an identity and culture of a nation.[118][105] Crimean Tatars call this event Sürgünlik ("exile").[119]

Genocide question and recognition

| # | Name | Date of recognition | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12 December 2015 | [120] | |

| 2 | 9 May 2019 | [121][122] | |

| 3 | 6 June 2019 | [123] | |

| 4 | 10 June 2019 | [124][125] |

Some activists, politicians, scholars, countries, and historians go even further and consider this deportation a crime of genocide.[126][127][128][129] Professor Lyman H. Legters argued that the Soviet penal system, combined with its resettlement policies, should count as genocidal since the sentences were borne most heavily specifically on certain ethnic groups, and that a relocation of these ethnic groups, whose survival depends on ties to its particular homeland, "had a genocidal effect remediable only by restoration of the group to its homeland".[129] Soviet dissidents Ilya Gabay[87] and Pyotr Grigorenko[130] both classified the event as a genocide. Historian Timothy Snyder included it in a list of Soviet policies that “meet the standard of genocide.”[131] Some academics disagree with the classification of deportation as genocide. Professor Alexander Statiev argues that Stalin's administration did not have a conscious genocidal intent to exterminate the various deported peoples, but that Soviet "political culture, poor planning, haste, and wartime shortages were responsible for the genocidal death rate among them." He rather considers these deportations an example of Soviet assimilation of "unwanted nations."[132] According to Professor Amir Weiner, "...It was their territorial identity and not their physical existence or even their distinct ethnic identity that the regime sought to eradicate."[133] According to Professor Francine Hirsch, "although the Soviet regime practiced politics of discrimination and exclusion, it did not practice what contemporaries thought of as racial politics." To her, these mass deportations were based on the concept that nationalities were "sociohistorical groups with a shared consciousness and not racial-biological groups".[134] In contrast to this view Jon K. Chang contends that the deportations had been in fact based on ethnicity; and that "social historians" in the west have failed to champion the rights of marginalized ethnicities in the Soviet Union.[135] On 12 December 2015, the Ukrainian Parliament issued a resolution recognizing this event as genocide and established 18 May as the "Day of Remembrance for the victims of the Crimean Tatar genocide."[120] The parliament of Latvia recognized the event as an act of genocide on 9 May 2019.[121][122] The Parliament of Lithuania did the same on 6 June 2019.[123] Canadian Parliament passed a motion on June 10, 2019, recognizing the Crimean Tatar deportation of 1944 (Sürgünlik) as a genocide perpetrated by Soviet dictator Stalin, designating May 18 to be a day of remembrance.[124][125]

In popular culture

In 2008, Lily Hyde, a British journalist living in Ukraine, published a novel titled Dreamland that revolves around a Crimean Tatar family return to their homeland in the 1990s. The story is told from the perspective of a 12-year-old girl who moves from Uzbekistan to a demolished village with her parents, brother, and grandfather. Her grandfather tells her stories about the heroes and victims among the Crimean Tatars.[136]

The 2013 Ukrainian Crimean Tatar-language film Haytarma portrays the experience of Crimean Tatar flying ace and Hero of the Soviet Union Amet-khan Sultan during the 1944 deportations.[137]

In 2015 Christina Paschyn released the documentary film A Struggle for Home: The Crimean Tatars in a Ukrainian–Qatari co-production. It depicts the history of the Crimean Tatars from 1783 up until 2014, with a special emphasis on the 1944 mass deportation.[138]

At the 2016 Eurovision Song Contest in Stockholm, Sweden, the Ukrainian Crimean Tatar singer Jamala performed the song 1944, which refers to the deportation of the Crimean Tatars in that year. Jamala an ethnic Crimean Tartar born in exile in Kyrgyzstan, dedicated the song to her deported great-grandmother. She became the first Crimean Tatar to perform at the Eurovision Song Contest and also the first to perform with a song with lyrics in her language. She won the event, becoming the second Ukrainian artist to win the event.[139]

References

- Buckley, Ruble & Hofmann (2008), p. 207

- Williams 2015, p. 109.

- Rywkin 1994, p. 67.

- Ukrainian Congress Committee of America 2004, pp. 43–44.

- Hall 2014, p. 53.

- Human Rights Watch 1991, p. 34.

- Allworth 1988, p. 6.

- Spring 2015, p. 228.

- Potichnyj 1975, pp. 302–319.

- Fisher 1987, pp. 356–371.

- Tanner 2004, p. 22.

- Vardys (1971), p. 101

- Smele 2015, p. 302.

- Olson, Pappas & Pappas 1994, p. 185.

- Rosefielde 1997, pp. 321–331.

- Parrish 1996, p. 104.

- Williams (2015), p. 92

- Burleigh, Michael (2001). The Third Reich: A New History. Macmillan. p. 748. ISBN 978-0-8090-9326-7.

- Fisher 2014, pp. 151–152.

- Williams (2001), p. 377

- Fisher 2014, p. 157.

- Drohobycky 1995, p. 73.

- Fisher 2014, p. 160.

- Fisher 2014, p. 156.

- Williams (2001), p. 381

- Allworth 1998, p. 177.

- Uehling 2004, p. 38.

- Williams (2001), pp. 382–384

- Журнал «Огонёк» № 45 - 46, 1944 г.

- "Узеир Абдураманов — Герой, славный сын крымскотатарского народа". www.qirimbirligi.ru. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- Kasyanenko, Nikita (14 April 2001). "...К сыну от отца — закалять сердца". Газета «День».

- Colborne, 19 May 2016

- Human Rights Watch 1991, p. 3.

- Banerji, 23 October 2012

- Williams (2001), p. 374–375

- Knight 1995, p. 127.

- Buckley, Ruble & Hoffman (2008), p. 231

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights 2016.

- Weiner 2003, p. 224.

- Tweddell & Kimball 1985, p. 190.

- Pohl (1999), p. 114

- Pohl 2000, p. 3.

- Levene 2013, p. 317.

- Magocsi 2010, p. 690.

- Garrard & Healicon 1993, p. 167.

- Merridale 2007, p. 261.

- Pohl (1999), p. 5

- Williams 2015, p. 106.

- Pohl (1999), p. 115

- Uehling 2004, p. 100.

- Sandole et al. 2008, p. 94.

- Bugay 1996, p. 46.

- Syed, Akhtar & Usmani 2011, p. 298.

- Stronski 2010, pp. 132–133.

- Williams (2001), p. 401

- Buckley, Ruble & Hoffman (2008), p. 238

- Amnesty International 1973, pp. 160–161.

- Kamenetsky 1977, p. 244.

- Pohl 2000, pp. 3–4.

- Viola 2007, p. 99.

- Kucherenko 2016, p. 85.

- Reid 2015, p. 204.

- Lillis 2014.

- Pohl 2000, p. 4.

- Reid 2015.

- Uehling 2004, p. 3.

- Human Rights Watch 1991, p. 33.

- Allworth 1998, p. 155.

- Garrard & Healicon 1993, p. 168.

- Human Rights Watch 1991, p. 37.

- Pohl 2000, p. 7.

- Human Rights Watch 1991, p. 9.

- Moss 2008, p. 17.

- Dadabaev 2015, p. 56.

- Travis 2010, p. 334.

- Pohl 2000, p. 10.

- Pohl 2000, p. 5.

- Tanner 2004, p. 31.

- Requejo & Nagel 2016, p. 179.

- Bazhan 2015, p. 182.

- Vardy, Tooley & Vardy 2003, p. 554.

- Shabad, 11 March 1984

- Williams 2015, p. 165.

- Williams (2001), p. 425

- Tanner 2004, p. 32.

- Williams 2015, p. 127.

- Fisher 2014, p. 150.

- Williams 2015, p. 129.

- Human Rights Watch 1991, p. 38.

- Kamm, 8 February 1992

- Bugay 1996, p. 213.

- BBC News, 18 May 2004

- Garrard & Healicon 1993, p. 173.

- Human Rights Watch 1991, p. 44.

- Prokopchuk, 8 June 2005

- Uehling 2002, pp. 388–408.

- Buckley, Ruble & Hoffman (2008), p. 237

- Allworth 1998, p. 214.

- Finnin 2011, pp. 1091–1124.

- Williams 2002, pp. 323–347.

- Williams (2001), p. 439

- Allworth 1998, p. 356.

- Williams (2001), p. 384

- Skutsch 2013, p. 1188.

- Dufaud 2007, pp. 151–162.

- Manley 2012, p. 40.

- Williams (2002), p. 386

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights 2014, p. 15.

- Nechepurenko, 26 April 2016

- UN News Centre, 20 May 2014

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights 2014, p. 13.

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights 2015, pp. 40–41.

- Reuters, 22 April 2014

- Wezel 2016, p. 225.

- Requejo & Nagel 2016, p. 180.

- Polian 2004, p. 318.

- Lee 2006, p. 27.

- Williams (2002), pp. 357–373

- Zeghidour 2014, pp. 83–91.

- Radio Free Europe, 21 January 2016

- "Foreign Affairs Committee adopts a statement on the 75th anniversary of deportation of Crimean Tatars, recognising the event as genocide". Saeima. 24 April 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- "Latvian Lawmakers Label 1944 Deportation Of Crimean Tatars As Act Of Genocide". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 9 May 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- "Lithuanian parliament recognizes Soviet crimes against Crimean Tatars as genocide". The Baltic Times. 6 June 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- "Borys Wrzesnewskyj".

- "Foreign Affairs Committee passes motion by Wrzesnewskyj on Crimean Tatar genocide".

- Tatz & Higgins 2016, p. 28.

- Uehling 2015, p. 3.

- Blank 2015, p. 18.

- Legters 1992, p. 104.

- Allworth 1998, p. 216.

- Snyder, Timothy (5 October 2010). "The fatal fact of the Nazi-Soviet pact". the Guardian. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- Statiev 2010, pp. 243–264.

- Weiner 2002, pp. 44–53.

- Hirsch 2002, pp. 30–43.

- K. Chang, Jon (8 April 2019). "Ethnic Cleansing and Revisionist Russian and Soviet History". Academic Questions. 32 (2): 270. doi:10.1007/s12129-019-09791-8.

- O'Neil, 1 August 2014

- Grytsenko, 8 July 2013

- International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam, 2016

- John, 13 May 2016

Comments

- Or, according to other sources, 423,100.[7]

Sources

Books

- Allworth, Edward (1998). The Tatars of Crimea: Return to the Homeland: Studies and Documents. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822319948. LCCN 97019110. OCLC 610947243.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bazhan, Oleg (2015). "The Rehabilitation of Stalin's Victims in Ukraine, 1953–1964: A Socio-Legal Perspective". In McDermott, Kevin; Stibbe, Matthew (eds.). De-Stalinising Eastern Europe: The Rehabilitation of Stalin's Victims after 1953. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137368928. OCLC 913832228.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Buckley, Cynthia J.; Ruble, Blair A.; Hofmann, Erin Trouth (2008). Migration, Homeland, and Belonging in Eurasia. Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press. ISBN 9780801890758. LCCN 2008015571. OCLC 474260740.

- Bugay, Nikolay (1996). The Deportation of Peoples in the Soviet Union. New York City: Nova Publishers. ISBN 9781560723714. OCLC 36402865.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dadabaev, Timur (2015). Identity and Memory in Post-Soviet Central Asia: Uzbekistan's Soviet Past. Milton Park: Routledge. ISBN 9781317567356. LCCN 2015007994. OCLC 1013589408.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Drohobycky, Maria (1995). Crimea: Dynamics, Challenges and Prospects. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780847680672. LCCN 95012637. OCLC 924871281.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fisher, Alan W. (2014). Crimean Tatars. Stanford, California: Hoover Press. ISBN 9780817966638. LCCN 76041085. OCLC 946788279.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garrard, John; Healicon, Alison (1993). World War 2 and the Soviet People: Selected Papers from the Fourth World Congress for Soviet and East European Studies. New York City: Springer. ISBN 9781349227969. LCCN 92010827. OCLC 30408834.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kamenetsky, Ihor (1977). Nationalism and Human Rights: Processes of Modernization in the USSR. Littleton, Colorado: Association for the Study of the Nationalities (USSR and East Europe) Incorporated. ISBN 9780872871434. LCCN 77001257.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Knight, Amy (1995). Beria: Stalin's First Lieutenant. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691010939. LCCN 93003937.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kucherenko, Olga (2016). Soviet Street Children and the Second World War: Welfare and Social Control under Stalin. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781474213448. LCCN 2015043330.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Jongsoo James (2006). The Partition of Korea After World War II: A Global History. New York City: Springer. ISBN 9781403983015. LCCN 2005054895.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Legters, Lyman H. (1992). "The American Genocide". In Lyden, Fremont J. (ed.). Native Americans and Public Policy. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 9780822976820. OCLC 555693841.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Levene, Mark (2013). The crisis of genocide: Annihilation: Volume II: The European Rimlands 1939-1953. New York City: OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780191505553. LCCN 2013942047.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Magocsi, Paul R. (2010). A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9781442610217. LCCN 96020027. OCLC 899979979.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Manley, Rebecca (2012). To The Tashkent Station: Evacuation and Survival in the Soviet Union at War. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801457760. OCLC 979968105.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Merridale, Catherine (2007). Ivan's War: Life and Death in the Red Army, 1939-1945. New York City: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 9780571265909. LCCN 2005050457.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moss, Walter G. (2008). An Age of Progress?: Clashing Twentieth-Century Global Forces. London: Anthem Press. ISBN 9780857286222. LCCN 2007042449. OCLC 889947280.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Motadel, David (2014). Islam and Nazi Germany's War. Harvard University Press. p. 235. ISBN 9780674724600. OCLC 900907482.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Olson, James Stuart; Pappas, Lee Brigance; Pappas, Nicholas Charles (1994). An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313274978. OCLC 27431039.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parrish, Michael (1996). The Lesser Terror: Soviet State Security, 1939-1953. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780275951139. OCLC 473448547.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pohl, J. Otto (1999). Ethnic Cleansing in the Ussr, 1937-1949. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313309212. LCCN 98046822. OCLC 185706053.

- Polian, Pavel (2004). Against Their Will: The History and Geography of Forced Migrations in the USSR. Budapest; New York City: Central European University Press. ISBN 9789639241688. LCCN 2003019544.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reid, Anna (2015). Borderland: A Journey Through the History of Ukraine. New York City: Hachette, UK. ISBN 9781780229287. LCCN 2015938031.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Requejo, Ferran; Nagel, Klaus-Jürgen (2016). Federalism Beyond Federations: Asymmetry and Processes of Resymmetrisation in Europe (repeated ed.). Surrey, England: Routledge. ISBN 9781317136125. LCCN 2010033623. OCLC 751970998.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rywkin, Michael (1994). Moscow's Lost Empire. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 9781315287713. LCCN 93029308. OCLC 476453248.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sandole, Dennis J.D.; Byrne, Sean; Sandole-Staroste, Ingrid; Senehi, Jessica (2008). Handbook of Conflict Analysis and Resolution. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781134079636. LCCN 2008003476. OCLC 907001072.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Skutsch, Carl (2013). Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781135193881. OCLC 863823479.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smele, Jonathan D. (2015). Historical Dictionary of the Russian Civil Wars, 1916-1926. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442252813. OCLC 985529980.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spring, Peter (2015). Great Walls and Linear Barriers. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword Books. ISBN 9781473853843. LCCN 2015458193.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Studies on the Soviet Union (1970). Studies on the Soviet Union. Munich: Institute for the Study of the USSR. OCLC 725829715.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stronski, Paul (2010). Tashkent: Forging a Soviet City, 1930–1966. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 9780822973898. LCCN 2010020948.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Syed, Muzaffar Husain; Akhtar, Saud; Usmani, B.D. (2011). A Concise History of Islam. New Delhi: Vij Books India. ISBN 9789382573470. OCLC 868069299.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tanner, Arno (2004). The Forgotten Minorities of Eastern Europe: The History and Today of Selected Ethnic Groups in Five Countries. Helsinki: East-West Books. ISBN 9789529168088. LCCN 2008422172. OCLC 695557139.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tatz, Colin; Higgins, Winton (2016). The Magnitude of Genocide. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781440831614. LCCN 2015042289. OCLC 930059149.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Travis, Hannibal (2010). Genocide in the Middle East: The Ottoman Empire, Iraq, and Sudan. Durham, N.C.: Carolina Academic Press. ISBN 9781594604362. LCCN 2009051514. OCLC 897959409.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tweddell, Colin E.; Kimball, Linda Amy (1985). Introduction to the Peoples and Cultures of Asia. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 9780134915722. LCCN 84017763. OCLC 609339940.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Uehling, Greta (2004). Beyond Memory: The Crimean Tatars' Deportation and Return. Palgrave. ISBN 9781403981271. LCCN 2003063697. OCLC 963444771.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vardy, Steven Béla; Tooley, T. Hunt; Vardy, Agnes Huszar (2003). Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-century Europe. New York City: Social Science Monographs. ISBN 9780880339957. OCLC 53041747.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Viola, Lynne (2007). The Unknown Gulag: The Lost World of Stalin's Special Settlements. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195187694. LCCN 2006051397. OCLC 456302666.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weiner, Amir (2003). Landscaping the Human Garden: Twentieth-century Population Management in a Comparative Framework. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804746304. LCCN 2002010784. OCLC 50203946.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wezel, Katja (2016). Geschichte als Politikum: Lettland und die Aufarbeitung nach der Diktatur (in German). Berlin: BWV Verlag. ISBN 9783830534259. OCLC 951013191.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williams, Brian Glyn (2001). The Crimean Tatars: The Diaspora Experience and the Forging of a Nation. Boston: BRILL. ISBN 9789004121225. LCCN 2001035369. OCLC 46835306.

- Williams, Brian Glyn (2015). The Crimean Tatars: From Soviet Genocide to Putin's Conquest. London, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190494728. LCCN 2015033355. OCLC 910504522.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Allworth, Edward (1988). Tatars of the Crimea: Their Struggle for Survival : Original Studies from North America, Unofficial and Official Documents from Czarist and Soviet Sources. Michigan: Columbia University. Center for the Study of Central Asia. ISBN 0822307588.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hall, M. Clement (2014). The Crimea. A very short history. ISBN 978-1-304-97576-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Online news reports

- Banerji, Robin (23 October 2012). "Crimea's Tatars: A fragile revival". BBC News. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- Colborne, Michael (19 May 2016). "For Crimean Tatars, it is about much more than 1944". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- Grytsenko, Oksana (8 July 2013). "'Haytarma', the first Crimean Tatar movie, is a must-see for history enthusiasts". Kyiv Post. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- John, Tara (13 May 2016). "The Dark History Behind Eurovision's Ukraine Entry". Time. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- Kamm, Henry (8 February 1992). "Chatal Khaya Journal; Crimean Tatars, Exiled by Stalin, Return Home". The New York Times.

- Lillis, Joanna (2014). "Uzbekistan: Long Road to Exile for the Crimean Tatars". EurasiaNet. Retrieved 4 August 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nechepurenko, Ivan (26 April 2016). "Tatar Legislature Is Banned in Crimea". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- O'Neil, Lorena (1 August 2014). "Telling Crimea's Story Through Children's Books". npr.org. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- Pohl, J. Otto (2000). "The Deportation and Fate of the Crimean Tatars" (PDF). self-published. Retrieved 4 August 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shabad, Theodore (11 March 1984). "Crimean Tatar Sentenced to 6th Term of Detention". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- "Crimean Tatars recall mass exile". BBC News. 18 May 2004. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- "A Struggle for Home: The Crimean Tatars". International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam. 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- "Ukraine's Parliament Recognizes 1944 'Genocide' Of Crimean Tatars". Radio Free Europe. 21 January 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- "Crimea Tatars say leader banned by Russia from returning". Reuters. 22 April 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- "The Ukrainian Quarterly, Volumes 60-61". Ukrainian Congress Committee of America. 2004. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- "Some 10,000 people in Ukraine now affected by displacement, UN agency says". UN News Centre. 20 May 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

Scientific journal articles

- Blank, Stephen (2015). "A Double Dispossession: The Crimean Tatars After Russia's Ukrainian War". Genocide Studies and Prevention. 9 (1): 18–32. doi:10.5038/1911-9933.9.1.1271.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dufaud, Grégory (2007). "La déportation des Tatars de Crimée et leur vie en exil (1944-1956): Un ethnocide?". Vingtième Siècle. Revue d'Histoire (in French). 96 (1): 151–162. doi:10.3917/ving.096.0151. JSTOR 20475182.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Finnin, Rory (2011). "Forgetting Nothing, Forgetting No One: Boris Chichibabin, Viktor Nekipelov, and the Deportation of the Crimean Tatars". The Modern Language Review. 106 (4): 1091–1124. doi:10.5699/modelangrevi.106.4.1091. JSTOR 10.5699/modelangrevi.106.4.1091.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fisher, Alan W. (1987). "Emigration of Muslims from the Russian Empire in the Years After the Crimean War". Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas. 35 (3): 356–371. JSTOR 41047947.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hirsch, Francine (2002). "Race without the Practice of Racial Politics". Slavic Review. 61 (1): 30–43. doi:10.2307/2696979. JSTOR 2696979.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Potichnyj, Peter J. (1975). "The Struggle of the Crimean Tatars". Canadian Slavonic Papers. 17 (2–3): 302–319. doi:10.1080/00085006.1975.11091411. JSTOR 40866872.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rosefielde, Steven (1997). "Documented homicides and excess deaths: New insights into the scale of killing in the USSR during the 1930s". Communist and Post-Communist Studies. 30 (3): 321–31. doi:10.1016/S0967-067X(97)00011-1. PMID 12295079.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Statiev, Alexandar (2010). "Soviet ethnic deportations: intent versus outcome". Journal of Genocide Research. 11 (2–3): 243–264. doi:10.1080/14623520903118961.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Uehling, Greta (2002). "Sitting on Suitcases: Ambivalence and Ambiguity in the Migration Intentions of Crimean Tatar Women". Journal of Refugee Studies. 15 (4): 388–408. doi:10.1093/jrs/15.4.388.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Uehling, Greta (2015). "Genocide's Aftermath: Neostalinism in Contemporary Crimea". Genocide Studies and Prevention. 9 (1): 3–17. doi:10.5038/1911-9933.9.1.1273.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vardys, V. Stanley (1971). "The Case of the Crimean Tartars". The Russian Review. 30 (2): 101–110. doi:10.2307/127890. JSTOR 127890.

- Weiner, Amir (2002). "Nothing but Certainty". Slavic Review. 61 (1): 44–53. doi:10.2307/2696980. JSTOR 2696980.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williams, Brian Glyn (2002). "Hidden ethnocide in the Soviet Muslim borderlands: The ethnic cleansing of the Crimean Tatars". Journal of Genocide Research. 4 (3): 357–373. doi:10.1080/14623520220151952.

- Williams, Brian Glyn (2002). "The Hidden Ethnic Cleansing of Muslims in the Soviet Union: The Exile and Repatriation of the Crimean Tatars". Journal of Contemporary History. 37 (3): 323–347. doi:10.1177/00220094020370030101. JSTOR 3180785.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zeghidour, Sliman (2014). "Le désert des Tatars". Association Médium (in French). 40 (3): 83. doi:10.3917/mediu.040.0083.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

International and NGO sources

- Prokopchuk, Natasha (8 June 2005). Vivian Tan (ed.). "Helping Crimean Tatars feel at home again". UNHCR. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- Amnesty International (1973). "A Chronicle of Current Events - Journal of the Human Rights Movement in the USSR" (PDF).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Human Rights Watch (1991). "Punished Peoples" of the Soviet Union: The Continuing Legacy of Stalin's Deportations" (PDF).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (2015). "Report on the human rights situation in Ukraine" (PDF). Retrieved 4 August 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (2014). "Report of the Special Rapporteur on minority issues, Rita Izsák - Addendum - Mission to Ukraine" (PDF). Retrieved 4 August 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (2016). Rupert Colville (ed.). "Press briefing notes on Crimean Tatars". Geneva. Retrieved 4 August 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links