Kerch Strait

The Kerch Strait (Russian: Керченский пролив, Ukrainian: Керченська протока, Crimean Tatar: Keriç boğazı) is a strait connecting the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, separating the Kerch Peninsula of Crimea in the west from the Taman Peninsula of Russia's Krasnodar Krai in the east. The strait is 3.1 kilometres (1.9 mi) to 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) wide and up to 18 metres (59 ft) deep.

| Kerch Strait | |

|---|---|

August 2011 landsat satellite photo | |

Kerch Strait | |

| Coordinates | 45°15′N 36°30′E |

| Max. length | 35 km (22 mi) |

| Max. width | 15 km (9.3 mi) |

| Min. width | 3.1 km (1.9 mi) |

| Average depth | 18 m (59 ft) |

| Islands | Tuzla Island |

The most important harbor, the Crimean city of Kerch, gives its name to the strait, formerly known as the Cimmerian Bosporus. The Krasnodar Krai side of the strait contains the Taman Bay encircled by Tuzla Island and the 2003 Russian-built 3.8 kilometres (2.4 mi)-long dam to the south and Chushka Spit to the north. Russia had started the construction of a major cargo port near Taman, the most important Russian settlement on the strait.

History

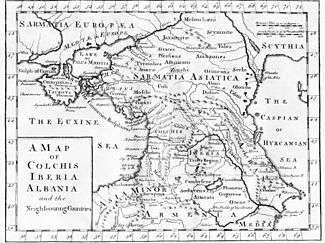

The straits are about 35 kilometers (22 mi) long and are 3.1 kilometers (1.9 mi) wide at the narrowest and separate an eastern extension of Crimea from Taman, the westernmost extension of the Caucasus Mountains. In antiquity, there seem to have been a group of islands intersected by arms of the Kuban River (Hypanis) and various sounds which have since silted up.[1] The Romans knew the strait as the Cimmerian Bosporus (Cimmerianus Bosporus) from its Greek name, the Cimmerian Strait (Κιμμέριος Βόσπορος, Kimmérios Bosporos), which honored the Cimmerians, nearby steppe nomads.[2] In ancient times the low-lying land near the Strait was known as the Maeotic Swamp.[3][4]

During the Second World War, the Kerch Peninsula became the scene of much desperate combat between forces of the Soviet Red Army and Nazi Germany. Fighting frequency intensified in the coldest months of year when the strait froze over, allowing the movement of troops over the ice.[5]

After the Eastern Front stabilized in early 1943, Hitler ordered the construction of a 4.8-kilometre (3.0 mi) road-and-rail bridge across the Strait of Kerch in the spring of 1943 to support his desire for a renewed offensive to the Caucasus. The cable railway (aerial tramway), which went into operation on 14 June 1943 with a daily capacity of one thousand tons, was only adequate for the defensive needs of the Seventeenth Army in the Kuban bridgehead. Because of frequent earth tremors, this bridge would have required vast quantities of extra-strength steel girders, and their transport would have curtailed shipments of military material to the Crimea. The bridge was never completed, and the Wehrmacht finished evacuating the Kuban bridgehead in September 1943.[6]

In 1944 the Soviets built a "provisional" railway bridge (Kerch railway bridge) across the strait. Construction made use of supplies captured from the Germans. The bridge went into operation in November 1944, but moving ice floes destroyed it in February 1945; reconstruction was not attempted.[7]

A territorial dispute between Russia and Ukraine in 2003 centred on Tuzla Island in the Strait of Kerch. Ukraine and Russia agreed to treat the strait and the Azov Sea as shared internal waters.[8]

Storm of November 2007

On Sunday 11 November 2007 news agencies reported a very strong storm on the Black Sea. Four ships sank, six ran aground on a sandbank, and two tankers were damaged, resulting in a major oil spill and the death of 23 sailors.[9]

The Russian-flagged oil tanker Volgoneft-139 encountered trouble in the Kerch Strait where it sought shelter from the above storm.[10] During the storm the tanker split in half, releasing more than 2000 tonnes of fuel oil. Four other boats sank in the storm, resulting in the release of sulphur cargo. The storm hampered efforts to rescue crew members.[11][12] Another victim of the storm, the Russian cargo ship Volnogorsk, loaded with sulfur, sank at Port Kavkaz on the same day.[13]

Ferry and bridge transportation

After the war, ferry transportation across the strait was established in 1952, connecting Crimea and the Krasnodar Krai (Port Krym – Port Kavkaz line). Originally there were four train ferry ships; later three car-ferry ships were added. Train transportation continued for almost 40 years. The aging train-ferries became obsolete in the late 1980s and were removed from service. In the autumn of 2004, new ships were delivered as replacements and train transportation was re-established. The ferry line stopped operations in late 2019.

Moscow mayor Yuri Luzhkov campaigned for a highway bridge to be constructed across the strait. Since 1944, various bridge projects to span the strait have been proposed or attempted, always hampered by the difficult geologic and geographic configuration of the area. Construction of an approach was actually started in 2003 with the 3.8 kilometres (2.4 mi)-long dam, provoking the 2003 Tuzla Island conflict.[14]

After the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea the government of Russia decided to build a bridge across the Kerch Strait. The 19-kilometre Crimean Bridge opened to road traffic in 2018 and the rail section opened in 2019.

Russian state-backed media claims that construction of the bridge caused increases in nutrients and planktons in the waters, attracting large numbers of fish and more than 1,000 of endangered Black Sea bottlenose dolphins.[15] However, Ukraine claims that the acoustic noise and pollution from both the bridge construction and military exercises may actually be killing Black Sea dolphins.[16]

In November 2018 the strait became a site of the Kerch Strait incident, in which the Russian navy claimed that three Ukrainian vessels entered Russian territorial waters. Russian forces seized the vessels and arrested their crew. During this time passage through the Strait under the bridge was blocked by a large cargo ship, placed under the bridge to prevent passage of other craft.[17][18]

Kerch–Yenikale Canal

In order to improve navigational capabilities of the Strait of Kerch, which is quite shallow in its narrowest point, the Kerch–Yenikale Canal was dredged through the strait. The canal/main channel can accommodate vessels up to 215 meters long with a draft of up to 8 meters with a compulsory pilot assistance. The canal is not straight and its geometry further complicates safe navigation. The narrowness, limited depth, and turns of the main channel together with the often unpredictable effects of wind and visibility (fog) there are strict procedures regulating strait transit. Transit of large vessels occurs on a one-way (alternating) group convoy basis. Transit procedures have remained unchanged, whether under Soviet, Ukrainian, or Russian jurisdiction. The Vessel Traffic Control Post in Kerch controls and oversees all traffic.

Fishing

Several fish-processing plants are located on the Crimean coast of the strait. The fishing season begins in late autumn and lasts for 2 to 3 months, when many seiners put out into the strait to fish. The Taman Bay is a major fishing ground, with many fishing villages scattered along the coast.

See also

- Kerch Strait incident (2019)

- Kerch Strait incident

References

-

- Anthon, Charles (1872) "Cimmerii" A Classical Dictionary: Containing an Account of the Principal Proper Names Mentioned in Ancient Authors (4th ed.) pp. 349–350.

- "Hun". Everything2.com. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- "Etruscan_Phrases, research providing new insight into Indo-European languages". Maravot.com. 13 February 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- Command Magazine, Hitler's Army: The Evolution and Structure of German Forces, Da Capo Press (2003), ISBN 0-306-81260-6, ISBN 978-0-306-81260-6, p. 264

- Inside the Third Reich by Albert Speer, Chapter 19, pg. 270 (1969, English translation 1970)

- "Archived copy" Мост через пролив. KERCH.COM.UA (in Russian). KERCH.COM.UA. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Agreement between the Russian Federation and the Ukraine on cooperation in the use of the sea of Azov and the strait of Kerch". www.ecolex.org. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- (in French) Marée noire: plus de 33.000 t de déchets pétroliers ramassés sur les plages du détroit de Kertch, 28 November 2007

- Chris Baldwin (12 November 2007). "Russia Tries to Contain Oil Spill, Save Seamen". Reuters. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Fuel spill disaster reported in waters near Russia". CNN. 11 November 2007. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- Arkady Irshenko (11 November 2007). "Russian oil tanker splits in half". BBC News. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- В порту "Кавказ" затонул сухогруз c серой, lenta.ru (11 November 2007)

- The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition

- Goldman E.. 2017. Crimean bridge construction boosts dolphin population in Kerch Strait. The Russia Beyond the Headlines. Retrieved on 10 March 2017

- "Ukrainian scientist: Dolphins in the Black Sea are dying because of the construction of the Kerch Strait bridge and military exercises". Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- "Ukraine–Russia clash: MPs back martial law". BBC News. 27 November 2018. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- "Ukraine accuses Russia of firing on its ships near Crimea", The Irish Times, 25 November 2018, retrieved 6 October 2019

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Strait of Kerch. |