Rock art

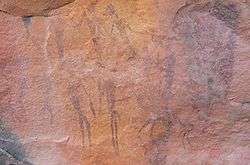

In archaeology, rock art is human-made markings placed on natural surfaces, typically vertical stone surfaces. A high proportion of surviving historic and prehistoric rock art is found in caves or partly enclosed rock shelters; this type also may be called cave art or parietal art. A global phenomenon, rock art is found in many culturally diverse regions of the world. It has been produced in many contexts throughout human history. In terms of technique, the main groups are: petroglyphs, which are carved or scratched into the rock surface, cave paintings, and sculpted rock reliefs. Another technique creates geoglyphs that are formed on the ground. The oldest known rock art dates from the Upper Palaeolithic period, having been found in Europe, Australia, Asia, and Africa. Anthropologists studying these artworks believe that they likely had magico-religious significance.

The archaeological sub-discipline of rock art studies first developed in the late-19th century among Francophone scholars studying the rock art of the Upper Palaeolithic found in the cave systems of parts of Western Europe. Rock art continues to be of importance to indigenous peoples in various parts of the world, who view them as both sacred items and significant components of their cultural heritage.[1] Such archaeological sites may become significant sources of cultural tourism and have been used in popular culture for their aesthetic qualities.[2]

Background

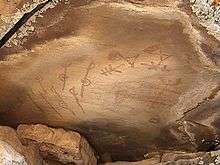

Parietal art is a term for art in caves, the definition usually extended to art in rock shelters under cliff overhangs. Popularly, it is called "cave art", and is a subset of the wider term, rock art. It is mostly on rock walls, but may be on ceilings and floors. A wide variety of techniques have been used in its creation. The term usually is applied only to prehistoric art, but it may be used for art of any date.[3] Sheltered parietal art has had a far better chance of surviving for very long periods, and what now survives may represent only a very small proportion of what was created.[4]

Both parietal and cave art refer to cave paintings, drawings, etchings, carvings, and pecked artwork on the interior of caves and rock shelters. Generally, these either are engraved (essentially meaning scratched) or painted, or, they are created using a combination of the two techniques.[5] Parietal art is found very widely throughout the world, and in many places new examples are being discovered.

The defining characteristic of rock art is that it is placed on natural rock surfaces; in this way it is distinct from artworks placed on constructed walls or free-standing sculpture.[6] As such, rock art is a form of landscape art, and includes designs that have been placed on boulder and cliff faces, cave walls, and ceilings, and on the ground surface.[6] Rock art is a global phenomenon, being found in many different regions of the world.[1] There are various forms of rock art. Some archaeologists also consider pits and grooves in the rock known as cupules, or cups or rings, as a form of rock art.[6]

Although there are exceptions, the majority of rock art whose creation was recorded by ethnographers had been produced during rituals.[6] As such, the study of rock art is a component of the archaeology of religion.[7]

Rock art serves multiple purposes in the contemporary world. In several regions, it remains spiritually important to indigenous peoples, who view it as a significant component of their cultural heritage.[1] It also serves as an important source of cultural tourism, and hence as economic revenue in certain parts of the world. As such, images taken from cave art have appeared on memorabilia and other artefacts sold as a part of the tourist industry.[2]

Types

Paintings

In most climates, only paintings in sheltered site, in particular caves, have survived for any length of time. Therefore these are usually called "cave paintings", although many do survive in "rock-shelters" or cliff-faces under an overhang. In prehistoric times these were often popular places for various human purposes, providing some shelter from the weather, as well as light. There may have been many more paintings in more exposed sites, that are now lost. Pictographs are paintings or drawings that have been placed onto the rock face. Such artworks have typically been made with mineral earths and other natural compounds found across much of the world. The predominantly used colours are red, black and white. Red paint is usually attained through the use of ground ochre, while black paint is typically composed of charcoal, or sometimes from minerals such as manganese. White paint is usually created from natural chalk, kaolinite clay or diatomaceous earth.[8] Once the pigments had been obtained, they would be ground and mixed with a liquid, such as water, blood, urine, or egg yolk, and then applied to the stone as paint using a brush, fingers, or a stamp. Alternately, the pigment could have been applied on dry, such as with a stick of charcoal.[9] In some societies, the paint itself has symbolic and religious meaning; for instance, among hunter-gatherer groups in California, paint was only allowed to be traded by the group shamans, while in other parts of North America, the word for "paint" was the same as the word for "supernatural spirit".[10]

One common form of pictograph, found in many, although not all rock-art producing cultures, is the hand print. There are three forms of this; the first involves covering the hand in wet paint and then applying it to the rock. The second involves a design being painted onto the hand, which is then in turn added to the surface. The third involves the hand first being placed against the panel, with dry paint then being blown onto it through a tube, in a process that is akin to air-brush or spray-painting. The resulting image is a negative print of the hand, and is sometimes described as a "stencil" in Australian archaeology.[11] Miniature stencilled art has been found at two locations in Australia and one in Indonesia.

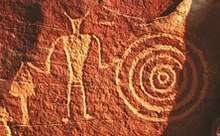

Petroglyphs

Petroglyphs are engravings or carvings into rock which is left in situ. They can be created with a range of scratching, engraving or carving techniques, often with the use of a hard hammerstone, which is battered against the stone surface. In certain societies, the choice of hammerstone itself has religious significance.[12] In other instances, the rock art is pecked out through indirect percussion, as a second rock is used like a chisel between the hammerstone and the panel.[12] A third, rarer form of engraving rock art was through incision, or scratching, into the surface of the stone with a lithic flake or metal blade. The motifs produced using this technique are fine-lined and often difficult to see.[13]

Rock reliefs

Normally found in literate cultures, a rock relie or rock-cut relief is a relief sculpture carved on solid or "living rock" such as a cliff, rather than a detached piece of stone. They are a category of rock art, and sometimes found in conjunction with rock-cut architecture.[14] However, they tend to be omitted in most works on rock art, which concentrate on engravings and paintings by prehistoric peoples. A few such works exploit the natural contours of the rock and use them to define an image, but they do not amount to man-made reliefs. Rock reliefs have been made in many cultures, and were especially important in the art of the Ancient Near East.[15] Rock reliefs are generally fairly large, as they need to be to make an impact in the open air. Most have figures that are over life-size, and in many the figures are multiples of life-size.

Stylistically they normally relate to other types of sculpture from the culture and period concerned, and except for Hittite and Persian examples they are generally discussed as part of that wider subject.[16] The vertical relief is most common, but reliefs on essentially horizontal surfaces are also found. The term typically excludes relief carvings inside caves, whether natural or themselves man-made, which are especially found in India. Natural rock formations made into statues or other sculpture in the round, most famously at the Great Sphinx of Giza, are also usually excluded. Reliefs on large boulders left in their natural location, like the Hittite İmamkullu relief, are likely to be included, but smaller boulders may be called stelae or carved orthostats.

Earth figures

Earth figures are large designs and motifs that are created on the stone ground surface. They can be classified through their method of manufacture.[17] Intaglios are created by scraping away the desert pavements (pebbles covering the ground) to reveal a negative image on the bedrock below. The best known example of such intaglio rock art is the Nazca Lines of Peru.[17] In contrast, geoglyphs are positive images, which are created by piling up rocks on the ground surface to resulting in a visible motif or design.[17]

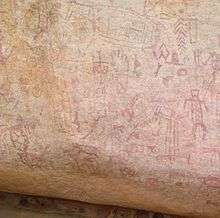

Motifs and panels

Traditionally, individual markings are called motifs and groups of motifs are known as panels. Sequences of panels are treated as archaeological sites. This method of classifying rock art however has become less popular as the structure imposed is unlikely to have had any relevance to the art's creators. Even the word 'art' carries with it many modern prejudices about the purpose of the features.

Rock art can be found across a wide geographical and temporal spread of cultures perhaps to mark territory, to record historical events or stories or to help enact rituals. Some art seems to depict real events whilst many other examples are apparently entirely abstract.

Prehistoric rock depictions were not purely descriptive. Each motif and design had a "deep significance" that is not always understandable to modern scholars.[18]

Interpretation and use

Religious interpretations

In many instances, the creation of rock art was itself a ritual act.[13]

Regional variations

Europe

In the Upper Palaeolithic of Europe, rock art was produced inside cave systems by the hunter-gatherer peoples who inhabited the continent. The oldest known example is the Chauvet Cave in France, although others have been located, including Lascaux in France, Alta Mira in Spain and Creswell Crags in Britain and Grotta del Genovese in Sicily.

The late prehistoric rock art of Europe has been divided into three regions by archaeologists. In Atlantic Europe, the coastal seaboard on the west of the continent, which stretches from Iberia up through France and encompasses the British Isles, a variety of different rock arts were produced from the Neolithic through to the Late Bronze Age. A second area of the continent to contain a significant rock art tradition was that of Alpine Europe, with the majority of artworks being clustered in the southern slopes of the mountainous region, in what is now south-eastern France and northern Italy.

- Finnish Rock Art

- Knowth

- Loughcrew

- Newgrange

- Rock Drawings in Valcamonica (World Heritage Site)

- Balma dei Cervi at Crodo (Piedmont - Italian Alps)

- Grotta dei Cervi at Porto Badisco (Apulia - Italy)

- Grotta del Genovese (Sicily)

- List of rock carvings in Norway

- Madara Rider (World Heritage Site)

- Côa Valley Paleolithic Art (World Heritage Site)

- Cave of Altamira and Paleolithic Cave Art of Northern Spain (World Heritage Site)

- Rock art of the Iberian Mediterranean Basin (World Heritage Site)

- Tanum (World Heritage Site)

- Tanums hällristningsmuseum,[19] Rock Art Research Centre and World Heritage Archive, situated in Tanum, Sweden.

Africa

North Africa

- South Oran in Algeria.

- Saharan rock art

- Tadrart Acacus in Libya – World Heritage Site.

- Tassili n'Ajjer in Algeria – national park and World Heritage Site, known for its 10,000-year-old paintings.

- Cave of Swimmers is a cave in southwest Egypt, near the border with Libya, along the western edge of the Gilf Kebir plateau in the central Libyan Desert (Eastern Sahara). It was discovered in October 1933 by the Hungarian explorer László Almásy. The site contains rock paintings of human figures who appear to be swimming, which have been estimated to have been created at least 6,000 to 7000 years ago. The Cave of Beasts 10 km westwards was discovered in 2002.

- Jebel Uweinat, a large granite and sandstone mountain, as well as the adjacent smaller massifs of Jebel Arkenu and Jebel Kissu at the converging triple borders of Libya, Egypt and Sudan, harbors one of the richest concentrations of prehistoric rock art in the entire Sahara. The rock art here mainly consists of the Neolithic cattle pastoralist cultures, but also a number of older paintings from hunter-gatherer societies.

- Sabu-Jaddi rock art site in Northern Sudan.

East Africa

- Qohaito in Eritrea – 7,000 years old rock art near the ancient city Qohaito.

- Dorra and Balho in Djibouti – Rock art sites with figures of what appear to be antelopes and a giraffe.

- Kundudo in Ethiopia – Flat top mountain complex with rock art in a cave.

- Laas Geel in Somalia – A number of cave paintings and petroglyphs can be found at various sites across the country. Among the most prominent examples of this is the rock art in Laas Geel, Dhambalin, Gaanlibah and Karinhegane.

- Nyero Rockpaintings, Uganda-World Heritage Site, pre-historic paintings was noticed before 1250 AD[20]

Southern Africa

Cave paintings are found in all parts of Southern Africa that have rock overhangs with smooth surfaces. Among these sites are the cave sandstone of Natal, Orange Free State and North-Eastern Cape, the granite and Waterberg sandstone of the Northern Transvaal, and the Table Mountain sandstone of the Southern and Western Cape.[21]

- UKhahlamba Drakensberg Park in South Africa – The site has paintings dated to around 3,000 years old and which are thought to have been drawn by the San people and Khoisan people, who settled in the area some 8,000 years ago. The rock art depicts animals and humans and is thought to represent religious beliefs.

- Tsodilo Hills in Botswana – A World Heritage Site with rock art

- Brandberg Mountain (Daureb) in Namibia – It is one of the most important rock art localities on the African continent. Most visitors only see "The White Lady" shelter (which is neither white, nor a lady, the famous scene probably depicts a young boy in an initiation ceremony), however the upper reaches of the mountain is full of sites with prehistoric paintings, some of which rank among the finest artistic achievements of prehistory.

- Bambata Cave, Zimbabwe- Animal paintings and human drawings are supposed to be age from 2.000 to 20.000 years old[22][23][24]

- Mwela and Adjacent Areas Rock Art Site, Zambia

The Americas

The oldest reliably dated rock art in the Americas is known as the "Horny Little Man." It is petroglyph depicting a stick figure with an oversized phallus and carved in Lapa do Santo, a cave in central-eastern Brazil.[25] The most important site is Serra da Capivara National Park at Piauí state. It is a UNESCO world heritage site with the largest collection in the American continent and one of the most studied.

Rock paintings or pictographs are located in many areas across Canada. There are over 400 sites attributed to the Ojibway from northern Saskatchewan to the Ottawa River.[26]

- Pomier Caves, Dominican Republic

- Naj Tunich, Guatemala

- Rock Paintings of Sierra de San Francisco, Baja California, Mexico

- Sierra de Guadalupe cave paintings, Baja California, Mexico

- Pictograph Cave Complex, Billings, Montana, United States

- Cañon Pintado, Colorado, United States

- Chaco Culture National Historical Park, New Mexico, United States

- Chumash rock art, California, United States

- Coso Rock Art District, California, United States

- Nine Mile Canyon, Utah, United States

- Quail rock art panel, Utah, United States

- Painted Rocks, Arizona, United States

- Petroglyph National Monument, New Mexico, United States

- Serra da Capivara National Park, Piauí, Brazil

- Vale do Catimbau National Park, Pernambuco, Brazil.

- Localidad Rupestre de Chamangá, Uruguay

- Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park, Alberta, Canada

- Cueva de las Manos, Santa Cruz Province, Argentina

- Huerfano Butte, Arizona, United States

- Petroglyphs Provincial Park, Ontario, Canada

Asia

Central Asia

- Gobustan National Park in Azerbaijan

- Petroglyphs of Arpa-Uzen, Kazakhstan

- Siypantosh Rock Paintings in Uzbekistan

- Zarautsoy Rock Paintings in Uzbekistan

East Asia

- Bangudae Petroglyphs, in South Korea

- Cheonjeon-ri in South Korea[27]

- Daegok-ri in South Korea[27]

- Fugoppe Cave petroglyphs on Hokkaido, Japan[27]

- Helankou in Yinchuan, China[27]

- Kangjia shimenzi in Xinjiang, China[27]

- Oponoho (Wanshan) petroglpyhs in Taiwan[27]

- Temiya Cave on Hokkaido, Japan[27]

- Yinshan petroglyphs in the Yin Mountains, China

- Zuo River Huashan rock art in Guangxi, China[27]

Southeast Asia

- Angono Petroglyphs, the Philippines

- Bir Hima Rock Petroglyphs and Inscriptions

- Pettakere cave, South Sulawesi, Indonesia – hand print paintings

- Pha Taem in Thailand

South Asia

- Bhimbetka rock shelters (World Heritage Site), Madhya Pradesh, India with rock art ranging from the Mesolithic (c.8,000 BC) to historical times[28][29][30][31][32][33]

- Edakkal Caves, Kerala India

- Gavali, Udupi

- Hire Benakal, Karnataka

- Balichakra, Yadgir town in Karnataka, India

- Rock paintings of Tamil Nadu, in India (several sites)[34]

- Kaimur district, Bihar, India (several sites)

- Rock paintings of Andhra Pradesh, in India (several sites)[34]

- Sonda, Karnataka

West Asia

- Rock Art in the Ha'il Region in Saudi Arabia

- Rock drawings were found in December 2016 near Khomeyn, Iran, which may be the oldest drawings discovered, with one cluster possibly 40,000 years old. Accurate estimations were unavailable due to US sanctions under the Donald Trump regime.[35] See rock art in Iran.

Australasia

Australia

Australian Indigenous art represents the oldest unbroken tradition of art in the world. There are more than 100,000 recorded rock art sites in Australia.[36]

The oldest firmly dated rock-art painting in Australia is a charcoal drawing on a rock fragment found during the excavation of the Nawarla Gabarnmang rock shelter in south western Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory. Dated at 28,000 years, it is one of the oldest known pieces of rock art on Earth with a confirmed date. Nawarla Gabarnmang is considered to have one of the most extensive collections of rock art in the world and predates both Lascaux and Chauvet cave art - the earliest known art in Europe - by at least 10,000 years.[37][38]

In 2008 rock art depicting what is thought to be a Thylacoleo was discovered on the north-western coast of the Kimberley.[39] As the Thylacoleo is believed to have become extinct 45000–46000 years ago (Roberts et al. 2001) (Gillespie 2004), this suggests a similar age for the associated Bradshaw rock paintings. Archaeologist Kim Akerman however believes that the megafauna may have persisted later in refugia (wetter areas of the continent) as suggested by Wells (1985: 228) and has suggested a much younger age for the paintings.[39] Pigments from the "Bradshaw paintings" of the Kimberley are so old they have become part of the rock itself, making carbon dating impossible. Some experts suggest that these paintings are in the vicinity of 50,000 years old and may even pre-date Aboriginal settlement.[40][41]

Miniature rock art of the stencilled variety at a rock shelter known as Yilbilinji, in the Limmen National Park in the Northern Territory, is one of only three known examples of such art. Usually stencilled art is life-size, using body parts as the stencil, but the 17 images of designs of human figures, boomerangs, animals such as crabs and long-necked turtles, wavy lines and geometric shapes are very rare. Found in 2017 by archaeologists, the only other recorded examples are at Nielson's Creek in New South Wales and at Kisar Island in Indonesia. It is thought that the designs may have been created by stencils fashioned out of beeswax.[42][43][44]

- Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory has a large collection of ochre paintings. Ochre is a not an organic material, so carbon dating of these pictures is impossible. Sometimes the approximate date, or at least an epoch, can be guessed from the content.

- The Sydney region has important rock engravings.

- Mount Grenfell Historic Site near Cobar, western New South Wales has important ancient rock-drawings.

- The Murujuga (Burrup Peninsula) area of Western Australia near Karratha is estimated to be home to between 500,000 and 1 million individual engravings.

- Kimberley region of Western Australia. Amateur archaeologist Grahame Walsh, who researched Bradshaw rock paintings in the region from 1977 until his death in 2007, produced a photographic database of 1.5 million Bradshaw rock paintings.[45] Many of the Bradshaw rock paintings maintain vivid colours because they have been colonised by bacteria and fungi, such as the black fungus, Chaetothyriales. The pigments originally applied may have initiated an ongoing, symbiotic relationship between black fungi and red bacteria.[46]

- The Grampians-Gariwerd region is Victoria is one of the richest Aboriginal rock art sites in south-eastern Australia.[47] Some of the more well-known and easily accessible sites are the Ngamadjidj Shelter (Cave of Ghosts), Gulgurn Manja (Flat Rock), Billimina (Glenisla Shelter) and Manja (Cave of Hands);[48] one of the most significant sites in south-eastern Australia is Bunjil's Shelter, near Stawell,[49] which is the only known rock art depiction of Bunjil, the creator-being in Aboriginal Australian mythology.[50]

New Zealand

In New Zealand, North Otago and South Canterbury have a rich range of early Māori rock art.[51]

- The Takiroa Rock Art Shelter near Duntroon contains Māori artwork made from ochre and charcoal.[52]

Rock art studies

The archaeological sub-discipline devoted to the investigation of rock art is known as "rock art studies." Rock art specialist David S. Whitley noted that research in this area required an "integrated effort" that brings together archaeological theory, method, fieldwork, analytical techniques and interpretation.[53]

History

Although French archaeologists had undertaken much research into rock art, Anglophone archaeology had largely neglected the subject for decades.[54]

The discipline of rock art studies witnessed what Whitley called a "revolution" during the 1980s and 1990s, as increasing numbers of archaeologists in the Anglophone world and Latin America turned their attention to the subject.[55] In doing so, they recognised that rock art could be used to understand symbolic and religious systems, gender relations, cultural boundaries, cultural change and the origins of art and belief.[1] One of the most significant figures in this movement was the South African archaeologist David Lewis-Williams, who published his studies of San rock art from southern Africa, in which he combined ethnographic data to reveal the original purpose of the artworks. Lewis-Williams would come to be praised for elevating rock art studies to a "theoretically sophisticated research domain" by Whitley.[56] However, the study of rock art worldwide is marked by considerable differences of opinion with respect to the appropriateness of various methods and the most relevant and defensible theoretical framework.

Introduction of the term

The term rock art appears in the published literature as early as the 1940s.[57][58] It has also been described as "rock carvings",[59] "rock drawings",[60] "rock engravings",[61] "rock inscriptions",[62] "rock paintings",[63] "rock pictures",[64] "rock records"[65] "rock sculptures.,[66][67]

International databases and archives

The UNESCO World Rock Art Archive Working Group met in 2011 to discuss the base model for a World Rock Art Archive.[68] While no official output has been generated to date various projects around the world, such as for example The Global Rock Art Database,[69][70] are looking at making rock art heritage information more accessible and more visible to assist with rock art awareness, conservation and preservation issues.

Notes

- Whitley 2005, p. 1.

- Whitley 2005, pp. 1–2.

- Bahn, 99-101

- Bahn, 101

- Bahn, 101-105

- Whitley 2005, p. 3.

- Whitley 2005. pp. 3–4.

- Whitley 2005, p. 4.

- Whitley 2005, pp. 4–5.

- Whitley 2005, p. 9.

- Whitley 2005, pp. 7–9.

- Whitley 2005, p. 11.

- Whitley 2005, p. 13.

- Harmanşah (2014), 5–6

- Harmanşah (2014), 5–6; Canepa, 53

- for example by Rawson and Sickman & Soper

- Whitley 2005, p. 14.

- Arca 2004, p. 319.

- "Scandinavian Society for Prehistoric Art". www.rockartscandinavia.se.

- "NYERO & OTHER ROCK ARTSITES IN EASTERN UGANDA" (PDF).

- Standard Encyclopaedia of Southern Africa (1973)

- "Stone Age - Africa". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-10-20.

- "Big Cave Camp | Famous Rock Art Galleries - visits to Nswatugi cave, Bambata, Silozwane cave, Inanke cave and Maholoholo cave". Big Cave. Retrieved 2018-10-20.

- https://austria-forum.org/, Austria-Forum |. "Rock Paintings Bambata Cave (1)". Global-Geography. Retrieved 2018-10-20.

- Choi, Charles. "Call this ancient rock carving 'little horny man'." Science on NBC News. 22 Feb 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- Grace Rajnovich. (1994) Reading rock art: interpreting the Indian rock paintings of the Canadian Shield. Toronto:Natural Heritage/Natural History Inc.

- O'Sullivan, Rebecca (2018). "East Asia: Rock Art". Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology (2 ed.). Springer. pp. 1–11. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-51726-1_3131-1. ISBN 978-3-319-51726-1.

- "Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka". World Heritage Site. Retrieved 2007-02-15.

- Mathpal, Yashodhar (1984). Prehistoric Painting Of Bhimbetka. Abhinav Publications. p. 220. ISBN 9788170171935.

- Tiwari, Shiv Kumar (2000). Riddles of Indian Rockshelter Paintings. Sarup & Sons. p. 189. ISBN 9788176250863.

- Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka (PDF). UNESCO. 2003. p. 16.

- Mithen, Steven (2011). After the Ice: A Global Human History, 20,000 - 5000 BC. Orion. p. 524. ISBN 9781780222592.

- Javid, Ali; Jāvīd, ʻAlī; Javeed, Tabassum (2008). World Heritage Monuments and Related Edifices in India. Algora Publishing. p. 19. ISBN 9780875864846.

- "Chapter -1 Introduction to Rock Art in India" (PDF).

- "Archaeologist uncovers 'the world's oldest drawings'". independent.co.uk. 12 December 2016.

- Griffiths, Billy (2018). Deep Time Dreaming: Uncovering Ancient Australia. Black Inc. p. 176.

- Barker, Bryce (18 June 2012). "Australia's oldest rock art discovered by USQ researcher". University of Southern Queensland. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- Collis, Clarisa (June 2012). "Ancient artists of rock and soul". Monash University. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- Akerman, Kim; Willing, Tim (March 2009). "An ancient rock painting of a marsupial lion, Thylacoleo carnifex, from the Kimberley, Western Australia". Antiquity. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- "The Times Literary Supplement – TLS". timesonline.co.uk.

- Bradshaw Foundation. "The Bradshaw Paintings – Australian Rock Art Archive". Bradshaw Foundation.

- Zwartz, Henry (27 May 2020). "Indigenous rock art found in the NT one of just three such examples worldwide". ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Flinders University (26 May 2020). "Miniature rock art expands horizons". Phys.org. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- "Archaeologists reveal rock art's big little secret". Flinders University (News). 27 May 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- "Rock Heart – Australian Story". abc.net.au. 15 October 2002.

- "Ancient rock art's colours come from microbes". BBC News. 27 December 2010.

- "National Heritage Places - Grampians National Park (Gariwerd)". Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment. Australian Government. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- "Aboriginal Rock Art Sites" (PDF). Brambuk. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- "Aboriginal Victoria, Grampians, Victoria, Australia". Visit Victoria. 5 October 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- "Bunjil Shelter - Stawell, Attraction, Grampians, Victoria, Australia". Visit Victoria. 30 March 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

-

Barrow, Terence (1978). Maori art of New Zealand (reprint ed.). Unesco Press. p. 70. ISBN 9789231013195. Retrieved 2018-03-06.

The North Otago and South Canterbury districts of the South Island present a rich range of rock art in red and black pigments. The motifs used are mainly humans, monsters, birds, and fish, and are styles which pre-date Classic Maori traditional art.

- McKinnon, Malcolm (29 July 2015). "Otago places - North Otago". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- Whitley 2005, p. xi.

- Whitley 2005. pp. viii, 1.

- Whitley 2005, p. x.

- Whitley 2005, p. viii.

- E. Goodall, Proceedings and Transactions of the Rhodesian Scientific Association 41:57-62, 1946: "Domestic Animals in rock art"

- E. Goodall, Proceedings and Transactions of the Rhodesian Scientific Association 42:69-74, 1949: "Notes on certain human representations in Rhodesian rock art"

- H. M. Chadwick, Origin Eng. Nation xii. 306, 1907: "The rock-carvings at Tegneby"

- H. A. Winkler, Rock-Drawings of Southern Upper Egypt I. 26, 1938: "The discovery of rock-drawings showing boats of a type foreign to Egypt."

- H. G. Wells, Outl. Hist. I. xvii. 126/1, 1920: From rock engravings we may deduce the theory that the desert was crossed from oasis to oasis.

- Deutsch, Rem. 177, 1874: "The long rock-inscription of Hamamât."

- Encycl. Relig. & Ethics I. 822/2, 1908: "The rock-paintings are either stenciled or painted in outline."

- Man No. 119. 178/2, 1939: "On one of the stalactite pillars was found a big round stone with traces of red paint on its surface, as used in the rock-pictures"

- G. Moore, The Lost Tribes and the Saxons of the East, 1861, Title page: "with translations of Rock-Records in India."

- Tylor, Early Hist. Man. v. 88, 1865, "and bush art or bushmen art."

- Trust For African Rock Art, East Africa, common terminology, "Rock-sculptures may often be symbolic boundary marks."

-

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre (2011). "World Rock Art Archives to meet in Tanum". Retrieved May 1, 2011.

- R., Haubt. "Rock-Art Database". www.rockartdatabase.com.

- Haubt, R.A.; Tacon, P.S.C. (October 22, 2016). "A collaborative, ontological and information visualization model approach in a centralized rock art heritage platform". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 10: 837–846. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2016.10.013.

References

- Arca, Andrea (2004). "The topographical engravings of Alpine rock-art: fields, settlements and agricultural landscapes". The Figured Landscapes of Rock-Art. Cambridge University Press. pp. 318–349.

- Bahn, Paul (ed), The Cambridge Illustrated History of Prehistoric Art, 1998, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521454735, 9780521454735, google books

- Devlet, Ekaterina (2001). "Rock Art and the Material Culture of Siberian and Central Asian Shamanism" (PDF). The Archaeology of Shamanism. pp. 43–54. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

- Harmanşah, Ömür (ed) (2014), Of Rocks and Water: An Archaeology of Place, 2014, Oxbow Books, ISBN 1782976744, 9781782976745

- Rawson, Jessica (ed). The British Museum Book of Chinese Art, 2007 (2nd edn), British Museum Press, ISBN 9780714124469

- Schaafsma, Polly, 1980, Indian Rock Art of the Southwest, School of American Research, Santa Fe, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque NM, ISBN 0-8263-0913-5. Scholarly text with 349 references, 32 color plates, 283 black and white "figures", 11 maps, and 2 tables.

- Sickman, Laurence, in: Sickman L., & Soper A., The Art and Architecture of China, Pelican History of Art, 3rd ed 1971, Penguin (now Yale History of Art), LOC 70-125675

- Whitley, David S. (2005). Introduction to Rock Art Research. Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press. ISBN 978-1598740004.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre (2011). "World Rock Art Archives to meet in Tanum". Retrieved May 1, 2011.

- Haubt, R.A.; Tacon, P.S.C. (October 22, 2016). "A collaborative, ontological and information visualization model approach in a centralized rock art heritage platform". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 10: 837–846. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2016.10.013.

Further reading

- David, Bruno, Cave Art, 2017, Thames and Hudson, ISBN 9780500204351

- Malotki, Ekkehart and Weaver, Donald E. Jr., 2002, Stone Chisel and Yucca Brush: Colorado Plateau Rock Art, Kiva Publishing Inc., Walnut, California, ISBN 1-885772-27-0 (cloth). For the "general public"; this book has well over 200 color prints with commentary on each site where the photos were taken; the organization begins with the earliest art and goes to modern times.

- B. B. Lal (1968). Indian Rock Paintings: Their Chronology, Technique and Preservation.

- Rohn, Arthur H. and Ferguson, William M, 2006, Puebloan Ruins of the Southwest, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque NM, ISBN 0-8263-3970-0 (pbk, : alk. paper). Adjunct to the primary discussion of the ruins, contains color prints of rock art at the sites, plus interpretations.

- Zboray, András, 2005, Rock Art of the Libyan Desert, Fliegel Jezerniczky, Newbury, United Kingdom (1st Edition 2005, 2nd expanded edition 2009). An illustrated catalogue and bibliography of all known prehistoric rock art sites in the central Libyan Desert (Arkenu, Uweinat and the Gilf Kebir plateau). The second edition contains more that 20000 photographs documenting the sites. Published on DVD-ROM.

External links

- Bradshaw Foundation Extensive archive on rock art from all around the world.

- Altarockart.no A digital archive of the Rock Art of Alta, Norway

- Global Rock Art Database (RADB) rockartdatabase, Global Rock Art Database (RADB) search tool for international rock art archives

- Maira Valley, Piedmont, Italy Rock Art in Maira Valley, Piedmont, Italy

- Chauvet Cave Database of European Prehistoric Art

- England's Rock Art on the Web Access to the ERA database containing over 1500 records of rock art panels with images and 3D models.

- Tassili N'Ajjer, Rock Art of the central Tassili N'Ajjer (Tamrit, Sefar, Tin Tazarift, Jabbaren)

- Uweinat and the Gilf Kebir, Rock Art of Jebel Uweinat and the Gilf Kebir plateau ("Cave of Swimmers")

- Upper Brandberg, The rock paintings of the Upper Brandberg, Namibia

- Libyan Desert, Rock Art of the Libyan Desert, and illustrated catalogue and bibliography of the prehistoric rock art of the central Libyan Desert

- Rupestreweb.info, Latin American rock art. Articles, Zones, News, Rock art researchers directory

- Tanums Hällristningsmuseum Rock Art Research Centre and World Heritage Archive, situated in Tanum, Sweden.

- Rock Art Studies (RAS) – A Bibliographic database at the Bancroft Library containing over 18,000 citations to the world's rock art literature.

- Rock Art Examples and Image Capture – Examples from the Côa Valley in Portugal and Magdalenian Rock Art.

- The Rock Art Foundation – Native American Rock Art in the Lower Pecos region of Southwest Texas

- Trust for African Rock Art

- Beckensall Archive Rock carvings made by Neolithic and Early Bronze Age people in Northumberland in the north east of England, between 6000 and 3500 years ago.

- British Rock Art Collection Over 16.000 photos of more than 1200 rock art sites in the UK with relevant information and links.

- Broken Rock Gallery and Petroglyph Designs.

- ARARA American Rock Art Research Association.

- Rupestre.net A rock art site, mainly devoted to Valcamonica and Alpine Rock Art.

- EuroPreArt The database of European Prehistoric Art.

- Rock Art of the Murujuga (Burrup Peninsula) Western Australia

- Rock Art in South Africa

- UNESCO World Heritage: Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka

- Bundelkhand Rock Paintings, India

- SpiralZoom.com, an educational website about the science of pattern formation, spirals in nature, spirals in the mythic imagination & spiral rock art

- Worldwide Rock Art Selection

- Rock Art in Israel

- Prehistoric Rock Art in Iran

- Petroglyphs in Iran (In Persian)

- Sydney Rock Art

- Rock Art in Oregon