Grampians National Park

The Grampians National Park commonly referred to as The Grampians, is a national park located in the Grampians region of Victoria, Australia. It lies within the region known as Gariwerd by Aboriginal Victorians of the area; Gariwerd extends across a wider area than the national park.[2]

| Grampians National Park / Gariwerd Victoria | |

|---|---|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

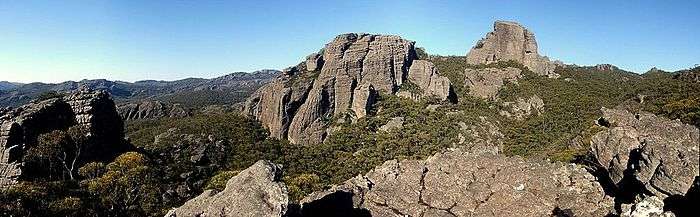

Grampians National Park / Gariwerd viewed from north of Boroka Peak | |

Grampians National Park / Gariwerd | |

| Nearest town or city | Halls Gap |

| Coordinates | 37°12′28″S 142°23′59″E |

| Established | 1 July 1984[1] |

| Area | 1,672.19 km2 (645.6 sq mi)[1] |

| Managing authorities | Parks Victoria |

| Website | Grampians National Park / Gariwerd |

| See also | Protected areas of Victoria |

The 167,219-hectare (413,210-acre) national park is situated between Stawell and Horsham on the Western Highway and Dunkeld on the Glenelg Highway, 260 kilometres (160 mi) west of Melbourne and 460 kilometres (290 mi) east of Adelaide. Proclaimed as a national park on 1 July 1984, the park was listed on the National Heritage List on 15 December 2006 for its outstanding natural beauty and being one of the richest Aboriginal rock art sites in south-eastern Australia.[3]

The Grampians feature a striking series of mountain ranges of sandstone. The Gariwerd area features about 90% of the rock art in the state.[2]

Etymology

At the time of European colonisation, the Grampians were called Gariwerd in the western Kulin Australian Aboriginal languages of the Jardwadjali and Djab Wurrung people who lived there and who shared 90 per cent of their vocabulary.[4] According to historian Benjamin Wilkie, the name Gariwerd was first written down in 1841, taken from a Jardwadjali speaker by the Chief Protector of Aborigines, George Augustus Robinson, as Currewurt. To the east, from speakers of the Djab Wurrung language or Djargurd Wurrung language he recorded "Erewurrr, country of the Grampians" – likely a mishearing of Gariwerd. Variations on Gariwerd recorded include Cowa, Gowah, and Gar – generic words for a pointed mountain. Elsewhere, Dhauwurd Wurrung language speakers from the southwest coast of Victoria called the mountains Murraibuggum, while Wathaurong language speakers used the name Tolotmutgo.[5]

In 1836, the explorer and Surveyor General of New South Wales Sir Thomas Mitchell renamed Gariwerd after the Grampian Mountains in his native Scotland. According to Wilkie, Mitchell first referred to Gariwerd as the Coast Mountains, and in July 1836 called them the Gulielmian Mountains after William IV of the United Kingdom (Gulielmi IV Regis)). Members of his expedition referred to the mountains as the Gulielmean, Gulielman, and the Blue Gulielmean Mountains. Later in 1836, Mitchell settled on the Grampians, and the Grampians National Park would also take this name in 1984.[6]

After a two-year consultation process, the park was renamed Grampians (Gariwerd) National Park in 1991, but that proved controversial and was reversed after a change of state government in 1992.[7] The Geographic Place Names Act, 1998 (Vic) reinstated dual naming for geographical features,[8] and this has been subsequently adopted in the park based on Jardwadjali and Djab Wurrung names for rock art sites and landscape features with the Australian National Heritage List, referring to "Grampians National Park (Gariwerd)".[3]

Physiography

This area is a distinct physiographic section of the larger Western Victorian Highlands province, which, in turn, is part of the larger East Australian Cordillera physiographic division.

Geography

The general form that the ranges take is: from the west, a series of low-angled sandstone ridges running roughly north-south. The eastern sides of the ridges, where the sedimentary layers have faulted, are steep and beyond the vertical in places - notably at Hollow Mountain near Dadswells Bridge at the northern end of the ranges. The most popular walking area for day trippers is the Wonderland area near Halls Gap. In summer the ranges can get very hot and dry. Winter and spring are the best times for walking. The Wonderland area is also host to "The Grand Canyon" on the "Wonderland Loop" on one of the tracks to the "Pinnacle".

In spring, the Grampians wildflowers are an attraction. The area is a rock climbing destination, and it is visited by campers and bushwalkers for its many views and its natural environment.

Mount William is known within the gliding community for the "Grampians Wave", a weather phenomenon enabling glider pilots to reach extreme altitudes above 28,000 ft (8,500 m). This predominantly occurs during the months of May, June, September and October when strong westerly winds flow at right angles to the ridge, and produce a large-scale standing wave (Mountain Lee Wave).[9]

Geology

The rock material that composes the high peaks is sandstone which was laid down from rivers during the Devonian period 425 - 415 million years ago.[10] This sediment slowly accumulated to a depth of 7 kilometres (4.3 mi); this was later raised and tilted for its present form. A number of stratigraphic layers have been identified, such as the Silverband Formation, the Mount Difficult Subgroup and the Red Man Bluff Subgroup.[10] The coarse grain and fine lamination of the Silverstone Formation, along with undulations at the surface, is thought to have been an estuarine backwater before becoming preserved around 400 million years ago.[11]

The Southern Ocean reached the base of the northern and western base of the mountain range about 40 million years ago, the deposition from the range forming the sea floor which is now Little Desert National Park.

The highest peak is Mount William at 1,167 metres (3,829 ft). Numerous waterfalls, such as Mackenzie Falls, are found in the park and are easily accessible via a well-developed road network.

Climate

| Climate data for Mount William, VIC (2005–2020]); 1,150 m AMSL; 37° 18′ 00.00″ S | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 36.6 (97.9) |

36.6 (97.9) |

32.2 (90.0) |

26.1 (79.0) |

18.0 (64.4) |

13.4 (56.1) |

12.1 (53.8) |

16.1 (61.0) |

20.6 (69.1) |

27.0 (80.6) |

32.1 (89.8) |

34.9 (94.8) |

36.6 (97.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 21.4 (70.5) |

20.3 (68.5) |

17.7 (63.9) |

12.7 (54.9) |

8.4 (47.1) |

6.3 (43.3) |

4.9 (40.8) |

5.8 (42.4) |

8.8 (47.8) |

12.9 (55.2) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.4 (65.1) |

12.8 (55.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 10.3 (50.5) |

9.7 (49.5) |

8.6 (47.5) |

6.1 (43.0) |

3.7 (38.7) |

2.0 (35.6) |

0.9 (33.6) |

1.0 (33.8) |

2.1 (35.8) |

4.0 (39.2) |

6.6 (43.9) |

7.9 (46.2) |

5.2 (41.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.9 (33.6) |

1.8 (35.2) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 67.1 (2.64) |

35.0 (1.38) |

53.3 (2.10) |

74.1 (2.92) |

134.6 (5.30) |

123.2 (4.85) |

177.6 (6.99) |

155.3 (6.11) |

116.6 (4.59) |

76.1 (3.00) |

70.2 (2.76) |

66.1 (2.60) |

1,149.2 (45.24) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 9.2 | 11.2 | 13.6 | 17.3 | 22.4 | 24.4 | 25.9 | 23.5 | 21.0 | 15.9 | 14.6 | 12.4 | 211.4 |

| Source: [12] | |||||||||||||

Cultural heritage

Evidence of vertebrate life

The Silverband Formation (see Geology above) was the source of sandstone paving slabs used for the construction of a nearby Cobb & Co station in 1873. The surface of one paver contain 23 impressions, the tracks of a four-legged animal around 850 millimetres (33 in) in length, which have been described as the oldest trace of a vertebrate walking on land.[11]

Aboriginal Australian heritage

To the Jardwadjali and Djab wurrung peoples, Gariwerd was central to the dreaming of the creator, Bunjil, and buledji Brambimbula, the two brothers Bram, who were responsible for the creation and naming of many landscape features in western Victoria.

Grampians National Park (Gariwerd) is one of the richest Indigenous rock art sites in south-eastern Australia and was listed on the National Heritage List for its natural beauty as well as its past and continuing Aboriginal cultural associations.[13] Motifs painted in numerous caves include depictions of humans, human hands, animal tracks and birds. Notable rock art sites include:[3][14]

- Billimina (Glenisla shelter)

- Jananginj Njani (Camp of the Emu's Foot)

- Manja (Cave of Hands)

- Larngibunja (Cave of Fishes)

- Ngamadjidj (Cave of Ghosts - the same word as that used for white people)

- Gulgurn Manja (Flat Rock)

The rock art was created by Jardwadjali and Djab Wurrung peoples, and while Aboriginal communities continue to pass on knowledge and cultural traditions, much Indigenous knowledge has also been lost since European settlement of the area from 1840. The significance of the right hand prints at Gulgurn Manja is now unknown.[15]

One of the most significant Aboriginal cultural sites in south-eastern Australia is Bunjil's Shelter, not within the park area, but in Black Range Scenic Reserve near Stawell.[16] It is the only known rock art depiction of Bunjil, the creator-being in Aboriginal Australian mythology.[17]

Dual naming of features has been adopted in the park based on Jardwadjali and Djab Wurrung names for rock art sites and landscape features, including:[18]

- Grampians / Gariwerd (mountain range)

- Mount Zero / Mura Mura (little hill)

- Halls Gap / Budja Budja

Recreation

Gariwerd and the Grampians National Park has been a popular destination for recreation and tourism since the middle of the nineteenth century. According to Wilkie, the extension of railways to nearby Stawell, Ararat and Dunkeld were an important factor in the mountains' increasing popularity in the early twentieth century; growing car ownership and the construction of tourist roads in the ranges during the 1920s were also significant.[19]

Rock climbing

The Grampians is a famous rock climbing destination, with the first routes being established in the 1960s.[20] Notable routes include The Wheel of Life (V15 / 35) and Groove Train (33) which attract world class climbers.[21]

In March 2019, 30% of climbing areas were closed by Parks Victoria due to cultural and ecological concerns, namely bolting, chalk marks, and making access paths through vegetation.[22][20][23] It closed 70% of bouldering routes, and 50% of sport climbing.[24]

Parks Victoria were accused by climbers of exaggerating damage and acting heavy handedly by pitting them against traditional owners, of whom they are "natural allies".[25][23][26]

Bushwalking

In 2015 Parks Victoria started building the 160km Grampians Peaks Trail.[27] The trail, which takes inspiration from popular Tasmanian trails, is designed to take 13 days to walk and crosses the length of the park.[28] It is due to be completed in 2020.[29]

Tourist centres

Halls Gap / Budja Budja is the largest service town in the area and is located at a point roughly equidistant between the towns of Ararat and Stawell. The town is located towards the eastern side of the park and offers accommodation to the many tourists who visit the area.

The Brambuk National Park and Cultural Centre in Halls Gap is owned and managed by Jardwadjali and Djab Wurrung people from five Aboriginal communities with historic links to the Gariwerd-Grampians ranges and the surrounding plains.[30]

Food and Wine Festival

Grampians National Park is home to one of Australia's longest running food and wine festivals, Grampians Grape Escape, held over the first weekend of May in Halls Gap every year. Launched in 1992, the Grampians Grape Escape is a hallmark event for Victoria and provides food and wine offerings by more than 100 local artisan producers, live music and family entertainment.[31]

Natural disasters

A major bushfire burned out about 50% of the Grampians National Park in January 2006. Soon afterwards the first signs of regeneration were already visible with, for example, regrowth of the eucalyptus trees. Many trees exhibit epicormic growth, where a mass of young shoots re-sprout along the whole length of the trunk to the base of the tree. Major flooding followed 5 years later in January 2011, forcing the closure of some parts of the Grampians National Park for several months.

Further reading

- Wilkie, Benjamin (2020). Gariwerd: An Environmental History of the Grampians. Melbourne: CSIRO Publishing ISBN 9781486307685

- Wettenhall, Gib and Pouliot, A. (2007). Gariwerd: Reflecting on the Grampians. Ballarat: Empress.

- Wettenhall, Gib (1999). The People of Gariwerd: The Grampians’ Aboriginal Heritage. Melbourne: Aboriginal Affairs Victoria.

- Calder, Jane (1987). The Grampians: A Noble Range. Melbourne: Victorian National Parks Association.

See also

References

- "Grampians National Park Management Plan" (PDF). Parks Victoria (PDF). March 2003. p. 10. ISBN 0-7311-3131-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- "Gariwerd/Grampians". Budja Budja Aboriginal Cooperative. 23 October 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- "National Heritage Places - Grampians National Park (Gariwerd)". Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment. Australian Government. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- Wilkie, Benjamin (2020). Gariwerd: An Environmental History of the Grampians. Melbourne: CSIRO Publishing. p. 22. ISBN 9781486307685.

- Wilkie, Benjamin (2020). Gariwerd: An Environmental History of the Grampians. Melbourne: CSIRO Publishing. p. 22. ISBN 9781486307685.

- Wilkie, Benjamin (2020). Gariwerd: An Environmental History of the Grampians. Melbourne: CSIRO Publishing. pp. 43–44. ISBN 9781486307685.

- Wilkie, Benjamin (2018). "Rights, reconciliation, and the restoration of Djabwurrung and Jardwadjali names to Grampians-Gariwerd". Victorian Historical Journal. 89 (1): 113–135.

- "Grampians (Gariwerd) National Park". Vicnames. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- "Wonderland Loop (25km) - TRAIL HIKING AUSTRALIA". TRAIL HIKING AUSTRALIA. 26 July 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- "Australian Stratigraphic Units Database, Geoscience Australia". Australian Stratigraphic Units Database. Australian Government. Geoscience Australia. 3 September 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- Vickers-Rich, P. (1993). Wildlife of Gondwana. NSW: Reed. pp. 103–104. ISBN 0730103153.

- "Climate statistics for Grampians (Mount William)". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- "Grampians National Park (Gariwerd), Victoria" (PDF). Australian Government. Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- C.F.M. Bird and D. Frankel, 2005. An Archaeology of Gariwerd. From Pleistocene to Holocene in Western Victoria. Tempus 8. (Archaeology and Material Culture Studies in Anthropology) University of Queensland, St Lucia.

- "A compelling case for beauty". The Age. 28 December 2005. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- "Aboriginal Victoria, Grampians, Victoria, Australia". Visit Victoria. 5 October 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- "Bunjil Shelter - Stawell, Attraction, Grampians, Victoria, Australia". Visit Victoria. 30 March 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- Ian D. Clark and Lionel L. Harradine, The restoration of Jardwadjali and Djab Wurrung names for rock art sites and landscape features in and around the Grampians National Park, Melbourne, Vic. : Koorie Tourism Unit, 1990.

- Wilkie, Benjamin (2020). Gariwerd: An Environmental History of the Grampians. Melbourne: CSIRO Publishing. pp. 95–97. ISBN 9781486307685.

- Slavsky, Bennett (21 March 2019). "Australia's Grampians National Park Announces Sweeping Climbing Closures". Climbing Magazine.

- "Jorg Verhoeven Sends Groove Train (33/5.14b) - Grampians, Australia". Rock and Ice. 29 February 2016.

- https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-04-29/grampians-national-park-bans-rock-climbers-over-rock-art-damage/11030190

- "Climbing Bans in the Grampians". Vertical Life. 14 February 2019.

- https://savegrampiansclimbing.org/

- https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/jul/02/grampians-rock-climbing-ban-could-be-softened-if-cultural-heritage-respected

- https://www.verticallifemag.com.au/2019/08/reconciliation/

- https://www.theaustralian.com.au/travel/the-grampians-worlds-next-epic-trek-a-peak-attraction/news-story/74cd7075ff78806501c091c80c745a0f

- https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/144kilometre-walking-track-to-showcase-the-highlights-of-the-grampians-20150622-ghuis0.html

- https://www.stawelltimes.com.au/story/6009079/company-signed-on-to-complete-grampians-peaks-trail-construction/

- About Brambuk National Park and Cultural Centre, Brambuk National Park and Cultural Centre website. Accessed 25 November 2008

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Thomas, Tyrone. 50 Walks in the Grampians. 5. Melbourne: Hill of Content, 1995.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Grampians National Park. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grampians National Park. |